Shays’ Rebellion: the laws that provoked the revolt (and the laws that succeeded in suppressing it)

Why were Massachusetts farmers sufficiently aggrieved during Shays’ Rebellion to risk imprisonment, forfeiture of their property, and the death penalty when they rose up in protest in the fall of 1786? What objectionable laws motivated their uprising? What actions did the Massachusetts Legislature adopt in response, during and after Shays’ Rebellion?

Part I of this post introduces the background behind Shays’ Rebellion from the perspective of the framers of the Constitution. Part I also provides an overview of the economics of Shays’ Rebellion and the heavy tax burden placed on farmers in western Massachusetts in 1786.

This post (Part II) discusses the laws passed by the Massachusetts Legislature (formally known as the “General Court”) that precipitated Shays Rebellion, as well as the laws passed during a Special Sessions beginning in the fall of 1786 that eventually succeeded in suppressing the Rebellion. It is hoped that by aggregating together these primary sources and legislative materials, students of history will gain a better understanding of the competing objectives – and fears – that motivated otherwise patriotic residents of western Massachusetts to take up arms.

Governor James Bowdoin’s tax program and the Congressional Requisition

In early 1785, John Hancock resigned as Governor in Massachusetts. After having easily won re-election for several years, Hancock was suffering from gout and was aware of growing criticism. In the three way race for governor, no candidate received a majority of the popular vote. James Bowdoin, a wealthy merchant, was selected by the Massachusetts Senate over lieutenant governor Thomas Cushing (an ally of Hancock) and Benjamin Lincoln (the first “Secretary at War” under the Articles of Confederation).

John Hancock, Massachusetts’ first post colonial governor, is pictured above. James Bowdoin, the state’s second governor and a rival of Hancock is pictured below.

In an address to the Massachusetts Legislature in May of 1785, Bowdoin spelled out the issues confronting his administration upon taking office. Recognizing that American access to foreign markets was restricted, Bowdoin identified the imbalance of foreign trade and “heavy debt” as the biggest economic problems facing the Commonwealth. Until a national trade policy could be implemented by Congress, Bowdoin suggested that Americans should “lessen the use of [imported] British commodities, most of which were superfluous and unnecessary.”

For Bowdoin, the solution was to “adopt a plan of frugality and economy, the want of which is the principal source of our difficulties.” Among other steps, Bowdoin outlined that it was necessary to reduce “unnecessary expenses,” pay down state debts, and manifest to “creditors and the world” that “public credit can be maintained or restored.”

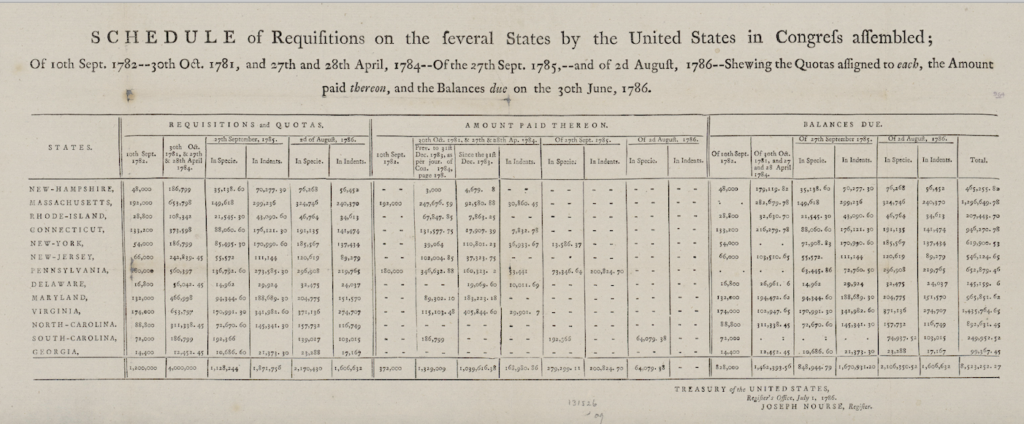

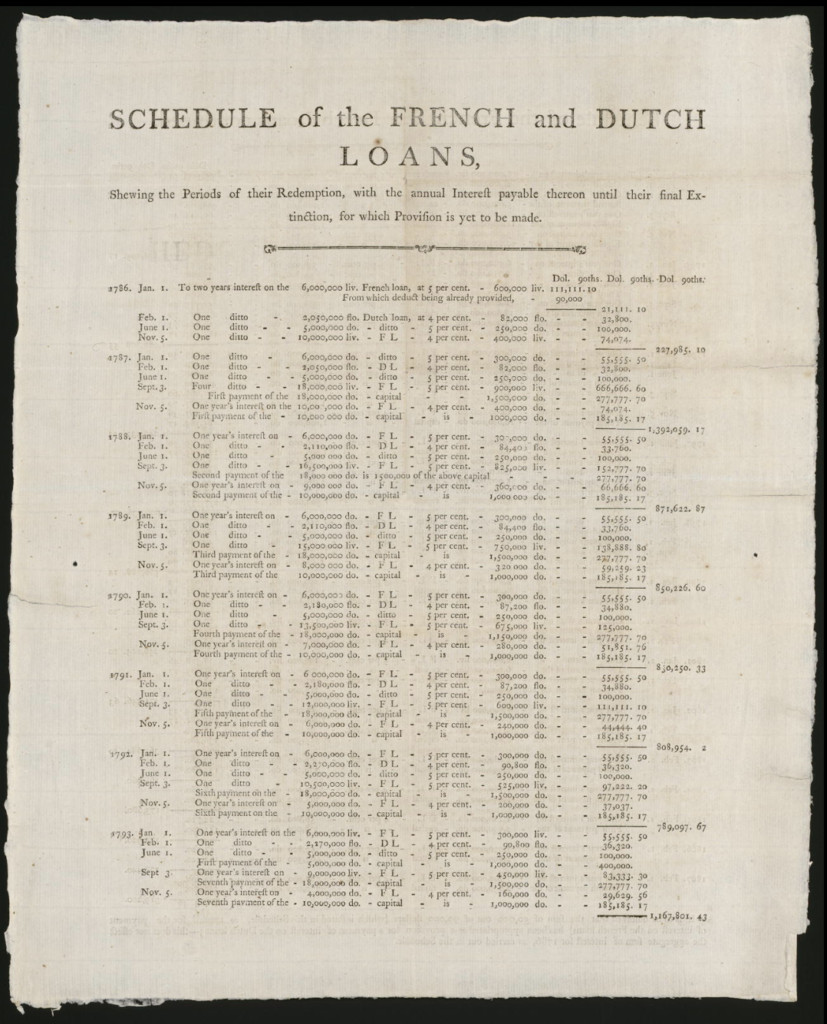

By itself, Bowdoin’s economic plans would require sacrifice. Yet, additional bad news was coming from the Confederation Congress. During the summer of 1785, Congress prepared a new “requisition” to the states for funding. As described by Congress, it was “incumbent” upon the several states “to exert themselves” to fulfill the duties they owe to their own character and the welfare of the confederacy,” by enacting “more efficacious” laws for the collection of taxes. Congress also advised the nation’s governors that it was facing looming interest payments which were due to the Dutch and French bankers that helped finance the Revolutionary War.

Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress only had the ability to make non-binding requests (called “requisitions”) on the states for funds. Amending the Articles required a unanimous vote of the states. In 1781 Rhode Island vetoed the impost bill that would have granting Congress the authority to impose a 5% tax on imports. The proposed impost of 1783 was vetoed by New York.

On October 20, 1785, in an address to a joint session of the Legislature, Bowdoin explained the financial difficulties facing the nation and the Commonwealth that required “speedy and effectual measures.” Bowdoin reported that based on the letter that he received from Congress dated August 24, a new round of taxes to satisfy the Congressional requisition has “become necessary and essential to the harmony of the Union.” Moreover, Bowdoin opined that “[p]unctuality in the payment of taxes is so essential to public credit, that the existence of the latter depends on it.”

Thus, in direct response to the Congressional requisition, Bowdoin called for the imposition of substantial new direct taxes in Massachusetts and a renewed emphasis on prompt tax collection. Bowdoin knew that his tax proposals would not be popular in the farming communities in the central and western parts of the state. Earlier in the year, the Massachusetts Legislature considered but rejected competing proposals from rural areas for debt relief and the issuance of more paper currency.

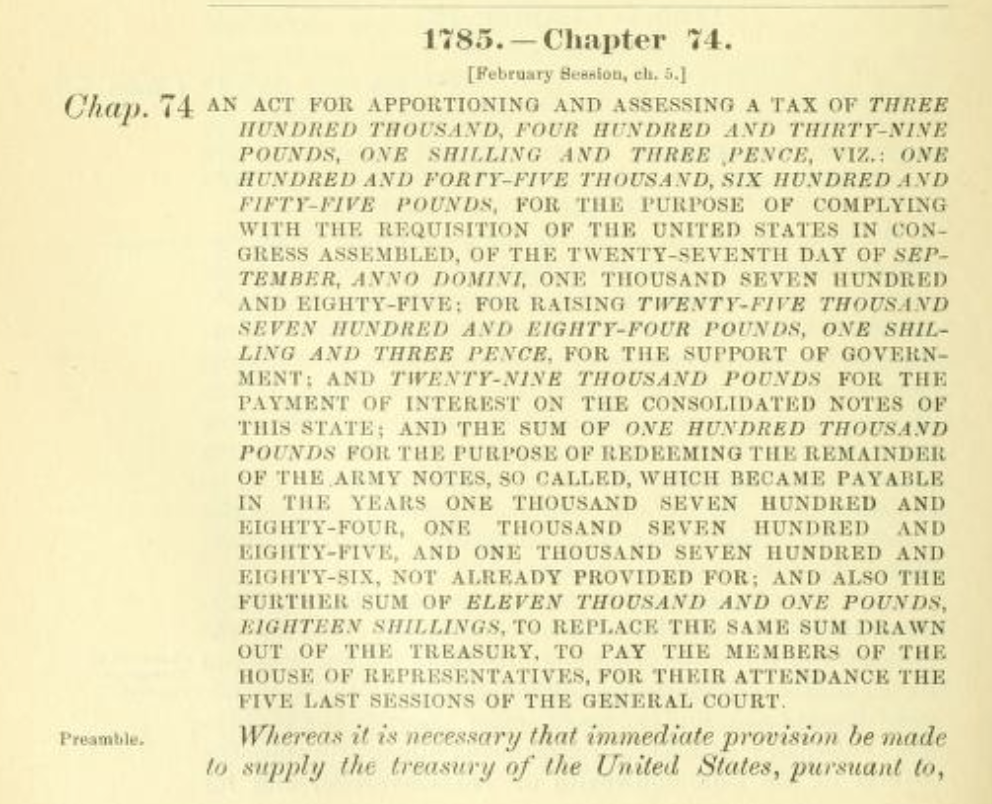

Ignoring petitions from western counties seeking debt and tax relief, on March 23, 1786, the Massachusetts Legislature enacted the largest direct tax in a generation. According to the whereas clauses in the “Act for Apportioning and Assessing a Tax of £300,439 it was “necessary that immediate provision be made to supply the treasury of the United States, pursuant to and in compliance with the requisition of the United States Congress.” As requested by Governor Bowdoin, half of the new tax would be used to pay the Congressional requisition. The remaining balance would largely be dedicated to paying interest on the Commonwealth’s debt.

Another frustration for famers was the requirement that one-third of the new tax would need to be paid in gold or silver coin (specie), the first time since 1781 that Massachusetts taxpayers were being asked to pay taxes in hard currency. The Legislature simultaneously saw fit to add teeth into the tax collection process. With the passage of an Act for Enforcing the Speedy Payment of Rates and Taxes in February of 1786, the tax collection laws were reorganized and strengthened. Tax collectors were required to provide more periodic updates to the state treasurer and tax officials were subject to replacement if their collections were deficient.

Further reinforcing its strict tax enforcement policy, in July of 1786 the Legislature approved a Resolve Respecting State Executions, with Directions to the Secretary to Publish the Same in Several Papers which made sheriffs personally responsible for uncollected taxes. To further insure compliance, the Legislature specifically directed that the new requirements be published in papers across the Commonwealth.

By aggressively trying to put Massachusetts’ financial house in order – while also attempting to fully complying with the Congressional requisition – Bowdoin departed company with other states. As described by historian Sean Condon, “other New England states did not choose this ambitious path.” For example, Condon explains that New Hampshire decided to delay interest payments on state loans. Connecticut prioritized its state debts and refused to pay its share of the requisition. Rhode Island authorized a direct tax of $20,000 in the summer of 1785 in anticipation of the federal requisition. The unpopularity of the tax in rural communities provoked a backlash. In the subsequent elections, the governor and half of the Rhode Island legislature lost reelection, replaced by a new legislature that approved a pro-debtor paper money policy.

Special Session of the Massachusetts Legislature

As Shays’ Rebellion and its resulting court closures began to erupt across western and middle counties in Massachusetts, Governor Bowdoin recalled the Legislature into special session. On September 25, in another address to a joint session, he explained that “tumults and disorders” had taken place in several counties, including the “obstructing” of the courts. Bowdoin conceded that “[w]hat led to the unwarrantable and lawless proceedings of those insurgents will be a necessary subject of serious inquiry.” Nevertheless, Bowdoin explained that regardless of their grievances, the insurgents’ actions were “anticonstitutional” and of a “very dangerous tendency,” particularly when “attempted by acts of violence” seeking to prevent “the execution of the laws and the due administration of justice.”

Bowdoin blamed the insurrection on “artful and wicked men” who were proceeding with “indefatigiable industry.” Bodwoin worried that the insurrection was “endeavoring to destroy all confidence in Government,” including “life, liberty and property.” Bowdoin may have been particularly distressed that when he had attempted to activate the militia he was confronted with widespread desertion in Worcester, Berkshire, Hampshire, Bristol and Middlesex counties. Worse yet, in several cases the militia appeared to “join the insurgents.” Bowdoin concluded his address by requesting “the most vigorous measures” to “vindicate the insulted dignity of Government” and address the “outrage” upon the courts:

I have thus laid before you, Gentlemen, an important part of the business, for which you are convened : and it cannot be doubted, that you will take the most vigorous measures, effectually to vindicate the insulted dignity of Government; enforce obedience to the laws; and secure the good people of the Commonwealth against all future infractions upon their peace; and in particular, against every outrage upon their Courts of Justice.

Remedial laws intended as carrots

According to historian Leonard Richards, Bowdoin engineered a “carrot-and-stick policy” to counter the insurrection. Mild carrots included several bills which: (i) lightened the tax burden by extending the due date for taxes from January 1 to April 1, 1787, (ii) eased the requirement for payment of taxes in hard currency, by permitting payment in kind using farm products and other commodities, (iii) imposed a new tax on imported luxury items such as jewelry, silver and ivory handled knives and forks, silk, carpets, and china; (iv) provided plans for the sale of 1,800 square miles of government land in Maine to raise additional revenue; (v) redirected one third of the new taxes from creditors to other governmental purposes; (vi) reduced legal fees by allowing justices of the peace to handle cases where the debt was four pounds or less; (vii) temporarily allowed the payment of certain private debts with land or personal property appraised by three impartial appraisers, in lieu of specie.

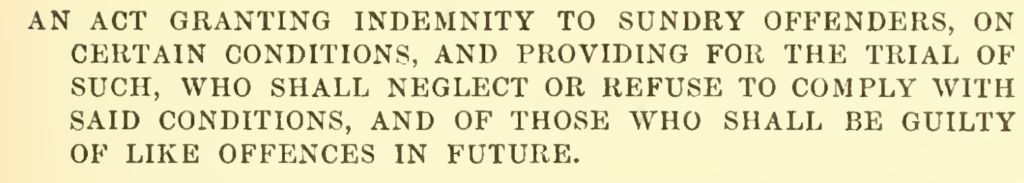

Perhaps the biggest carrot was the offer of a pardon (indemnity) for insurgents who had obstructed the courts between June 1 through the date of the Indemnity Act. The Indemnity Act of November 15, 1786 authorized pardons through January 1, 1787 in exchange for an oath of allegiance. As described by Bowdoin, the Indemnity Act offered “punishment on the one hand and pardon on the other.” While it was hoped that this offer would be warmly embraced, it turned out that only a single rioter took advantage of the act.

Along with the Indemnity Act, the following laws fit under the carrot category:

- An Act for Suspending the Laws for the Collection of Private Debts, under Certain Limitations

- An Act for Rendering Process in Law Less Expensive

- An Act Providing for the More Easy Payment of the Specie Taxes, Assessed Previous to the Year 1784

- An Act to Bring into the Public Treasury the Sum of 163,200 Pounds in Public Securities by a Sale of a Part of the Eastern Lands; and to Establish a Lottery for that Purpose

- An Act to Raise a Public Revenue by Impost

- An Act Appropriating the Revenue Arising from the Duties of Impost and Excise

- An Act Establishing and Regulating the Fees of the Several Officers and other Persons Hereafter Mentioned

Notwithstanding the above described measures, Bowdoin and the Legislature refused to accede to the rebels’ underlying demands. The request to issue paper money was rejected. The government declined to temporarily close the courts or reduce the Governor’s salary. The request to move the state capitol from Boston would be referred to a legislative committee for further review.

Harsh laws intended as sticks

The Riot Act

In compliance with Governor Bowdoin’s request that “vigorous” measures be undertaken, the legislature enacted a series of draconian laws that some might categorize as punitive. While the Shaysites rebels (referring to themselves as “Regulators”) were critical of the government from one end of the political spectrum, conservatives in Boston led by Sam Adams, called for harsh punishment. A celebrated rebel in his day against the British, Sam Adams now argued that “the man who dares rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death.” As a leading member of the Legislature, Adams actively assisted in the drafting of several retaliatory laws.

In a letter dated May 18, 1787 to John Adams, James Warren complained that Sam Adams was too punitive. “Our old friend Mr. A[dams] seems seems to have forsaken all his old principles & professions & to have become the most Arbitrary & despotic Man in the Commonwealth.”

As described by historian Ray Raphael, Samuel Adams “saw no contradiction between his earlier and current behavior. Public protest, even armed revolt, was legitimate when directed against a regime over which the people had no control, but not permissible against an elected, constitutional government.”

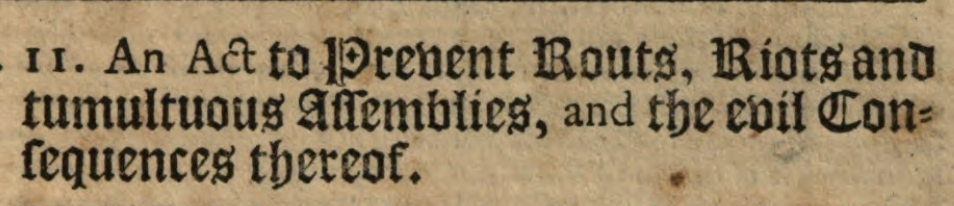

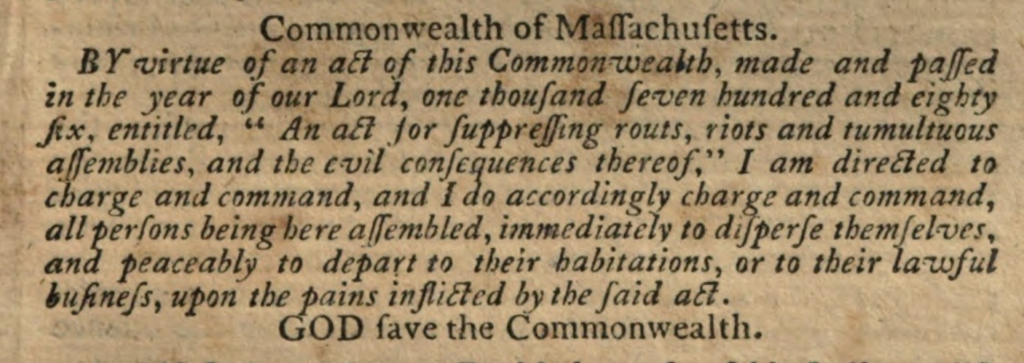

Arguably the most famous (and potentially most problematic) measure adopted to defeat the Shays’ Rebellion was the Riot Act of 1786. Formally titled An Act to Prevent Routs, Riots, and Tumultuous Assemblies and Evil Consequences Thereof, the Riot Act provided that sheriffs and other legal authorities “shall be indemnified and held guiltless” if anyone was killed or wounded during efforts to disperse or seize a crowd after “the reading of” the Riot Act.

By adopting the Act, Massachusetts borrowed a page from the hated “Intolerable Acts” which were enacted by the British following the Boston Tea Party. A generation earlier Massachusetts patriots decried the British Administration of Justice Act of 1774, which the American colonists labeled the “Murder Act”, since it effectively permitted British soldiers to act with impunity. Now the Riot Act would enable the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to get away with murder when responding to a so called “riot.”

The Riot Act applied to groups of twelve or more individuals armed with clubs or other weapons. Or, groups of thirty would also trigger the Act if “unlawfully, routously, riotously, or tumultuously assembled.” Under the Act, any justice of the peace, sheriff or constable was authorized to approach the riotous assembly, “or as near to them as he can safely come” and command silence while the following verbal warning was read:

If convicted of violating the Riot Act a defendant was subject to forfeiture of “all their lands, tenements, good and chattels,” to be applied to support the Commonwealth. Other penalties included imprisonment for up to twelve months with the further deterrent that every three months prisoners would receive “thirty nine stripes on the naked back at the public whipping post.”

The phrase “to read someone the riot act” has since passed into common usage, signifying that a stern warning has been issued. In 1792, a less robust version of the Riot Act was adopted by the new federal government. Click here for a discussion of the Militia Act of 1792 (otherwise known as the Calling Forth Act).

Suspension of Habeas Corpus

On November 10, 1786, the Massachusetts Legislature took the drastic step of suspending the writ of habeas corpus through July of 1787. The Act for Suspending the Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus authorized the Governor with advice and consent of the Council, to issue arrest warrants and indefinitely imprison any person “whom the Governor and Council shall deem the safety of the Commonwealth requires should be restrained of their personal liberty,” notwithstanding “any law, usage or custom tote contrary.”

Once apprehended, sheriffs could imprison arrestees “in any jail, or other safe place within the Commonwealth,” regardless of distance. The far reaching law granted “full power forceably to enter any dwelling house or other building” after first demanding entrance. Arresting authorities were empowered to require “aid and assistance” from citizens, who were themselves subject to forfeiture of up to £100 if they failed to cooperate.

On November 28, 1786, Governor Bowdoin deployed his authority under the November 10th Act Suspending Habeas Corpus. Bowdoin issued a warrant for the arrest of several insurrection leaders, including Job Shattuck. Several hundred light horsemen were sent to make the arrest. When Shattuck resisted, he was slashed across the knee with a broadsword.

According to historian Leonard Richards, the suspension of habeas corpus and the arrest of Shattuck and other leaders “set off a storm of protest.” Formal protests were submitted by more than thirty towns. Critics likened the government’s over-reaction to “British tyranny” which was condemned as “dangerous , if not absolutely destructive to a Republican government.”

Historian David Szatmary argues that the counter-insurgency by the Massachusetts government, “served further to radicalize many farmers.” “After the passage of anti-Shaysite legislation and the formation of the Lincoln expedition they came to recognize the fundamentally different outlooks that existed between themselves and their government and decided to oppose government rather than to rely upon the General Court (the Legislature) to effect change.”

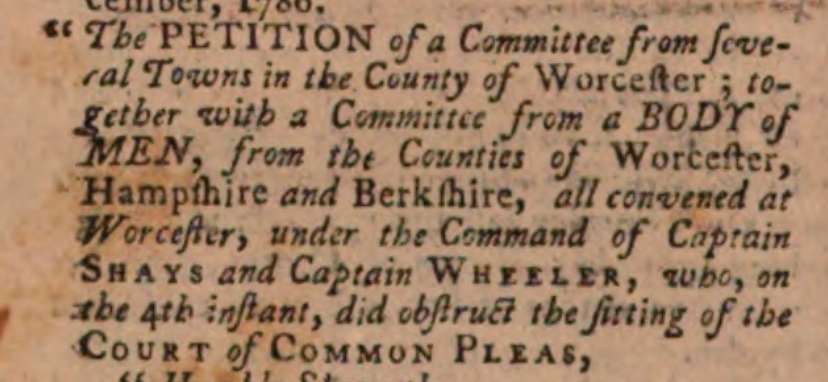

For example, a petition to Governor Bowdoin by several towns in the County of Worcester, “together with a committee from a body of men…. under the command of Captain Shays and Captain Wheeler” was printed in the Worcester Magazine in the second week of December of 1786. The petitioners begged leave to mention “their horror at the suspension of the privilege of habeas corpus.” They disputed that their complaints were “confined to a factious few.” Rather, Shays submitted that his criticism “extended to towns and counties and almost every individual who derives his living from the labor of his hands or an income of a farm.”

Militia Act

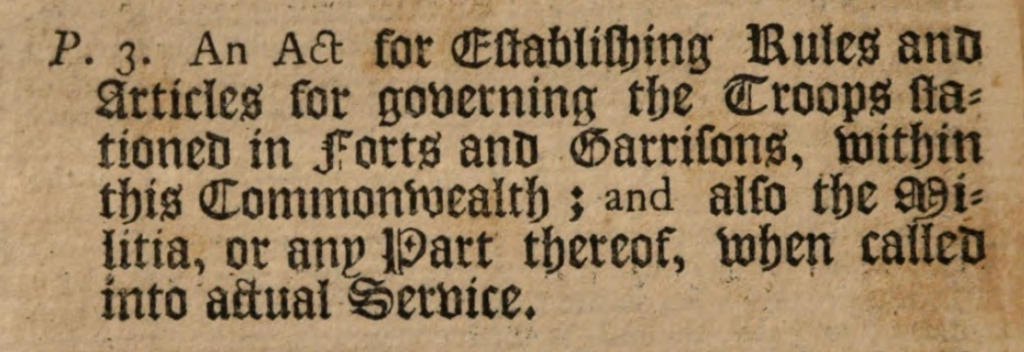

To address Governor Bowdoin’s concern about disloyalty by militia members, the Legislature adopted the draconian Militia Act of October 24, 1786. The Act for Establishing Rules and Articles for Governing Troops Stationed in Forts and Garrisons within this Commonwealth; and also the Militia, or any part thereof, when Called into Actual Service was squarely directed at those who refused to serve, deserted, or otherwise supported the insurgency.

Among other things, the detailed, sixty-two section Militia Act provided that “Whatsoever Officer or soldier shall abandon any post committed to his charge or shall speak words inducing others to do the like in time of an engagement, shall suffer death.” Likewise, “any officer or soldier who shall begin, excite, cause or join in any mutiny or sedition” was subject to “suffer such punishment as by court martial shall be inflicted,” including death, provided that “no sentence of death shall be given by any general court martial unless two thirds of the members shall concur therein.”

February 4, 1787 Formal Declaration of Rebellion

After the aborted attack on the Springfield armory, the Legislature reconvened. As described by historian Sean Condon, the January session of the legislature “emphasized punishment rather than relief.”

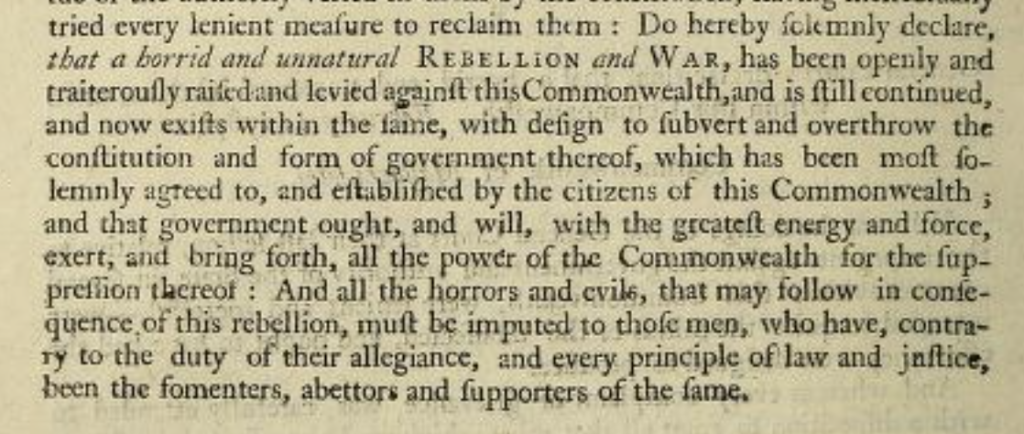

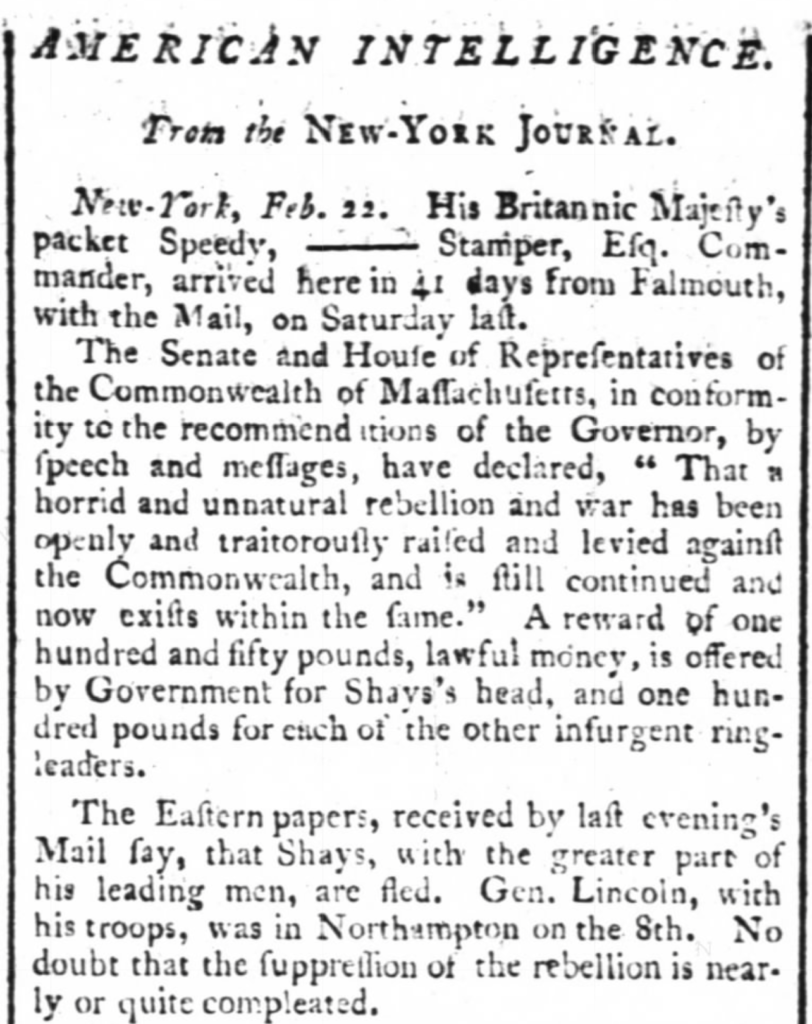

On February 4, a formal declaration was issued that “a horrid and unnatural rebellion exists within the Commonwealth.” The declaration, which is pictured below, indicated that the Commonwealth was in an open state of “rebellion and war.” After having previously tried “lenient measures,” the Legislature determined that the insurrectionists had taken up arms and evidenced “a settled determination to subvert that constitution and put an end to the government of this Commonwealth.” As a consequence, the Legislature committed to bring to bear “all the power of the Commonwealth” to suppress the rebellion.

In its February 4 address to the Governor, the Legislature praised “the patriotic zeal of a number of private citizens” who had advanced money or joined General Lincoln’s private militia. The legislature offered its assurances that these funds would be reimbursed “for this necessary and most important service.”

Disqualification Act

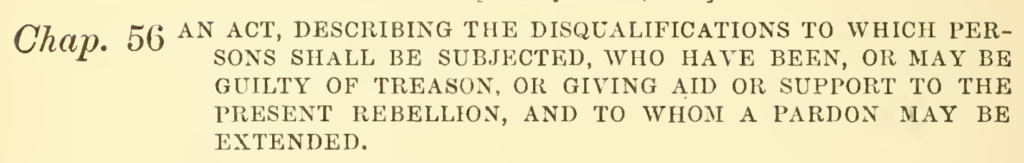

On February 16, the Legislature passed the Disqualification Act of 1787, officially titled An Act Describing the Disqualifications to which Persons Shall be Subjected, Who Have been or May be Guilty of Treason, or Giving Aid and Support to the Present Rebellion, and to Whom a Pardon May be Extended. Among other things, the Act clarified who was eligible for pardons and established a formalized pardon process.

For a three year period, the Disqualification Act banned insurgents from holding public office, serving on a jury, voting, or working in influential positions in the community including schoolmasters, innkeepers, or selling spirituous liquor. Beginning on May 1, 1788, those who exhibited “plenary evidence” of loyalty including “an unequivocal attachment to the government” could be “discharged” and resume their former occupation.

The Act also set forth conditions for pardons. Repentant insurgents were required to surrender their arms, pay a nine pence fee, and take an oath of allegiance administered by a justice of the peace. The names of oath takers were provided to towns clerks. Pardons were not available for insurgent leaders, those who took an oath but later rejoined the insurgency, or those who had fired a weapon at a government troops or supporters.

The Act was calibrated to motivate followers to leave the insurgency or suffer the consequences. All offenders who did not comply with the Act and “deliver up their arms” were to be treated “as rebels and open enemies.” Civil and military authorities were directed to “encounter, pursue, conquer, apprehend, and secure them” for trial and punishment.

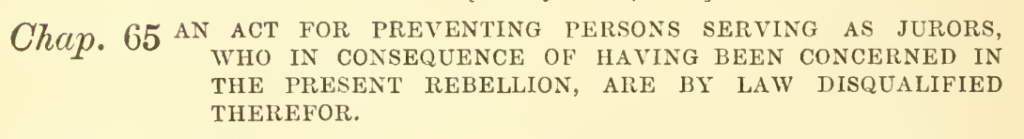

Ten days after the adoption of the Disqualification Act the Legislature directed local officials to remove anyone from jury rolls who was deemed to “have been guilty of favoring the present rebellion, or of giving aid or support thereto.” Click here for a link to the Act for Preventing Persons Serving as Jurors, Who in Consequence of Having Been Concerned in the Present Rebellion, are by Law Disqualified Therefor.

Additionally, the Act allowed litigants to challenge biased jurors. Similar in concept to a modern peremptory challenge, “upon motion” to the court a juror was to be put under oath to determine whether they were “sensible of any prejudice.” If it appeared to the court that “any juror does not stand indifferent in the cause” they were to be replaced by the judge with another juror. The Act further explained that it was “necessary for the impartial administration of justice that effectual measures be taken to prevent those who having been concerned in the present rebellion” be barred from serving as jurors in cases of treason.

Subsequently, an influential three member pardon commission was established by the Legislature. General Benjamin Lincoln, Senate President Samuel Phillips and state representative Samuel A. Otis were appointed to travel to western counties to interview those who were not otherwise eligible for pardons. At the end of April the commissioners submitted their report offering pardons for 790 individuals who had been interviewed and submitted affidavits of two men of unquestioned loyalty affirming that the former insurgent was “duly penitent for his crime, properly disposed to return to the allegiance of the State, and to discharge the duty of a faithful citizen thereof.”

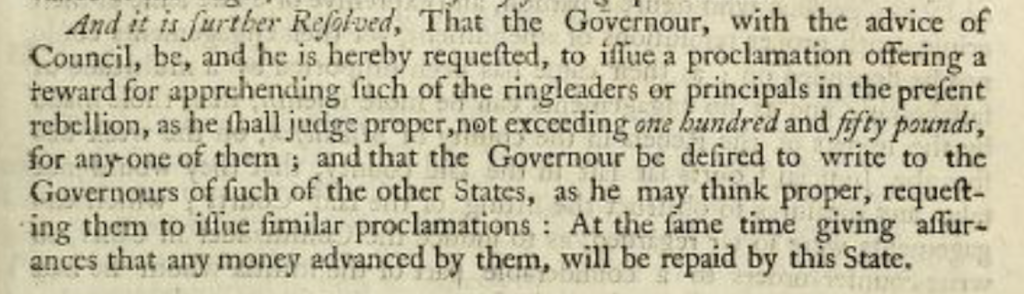

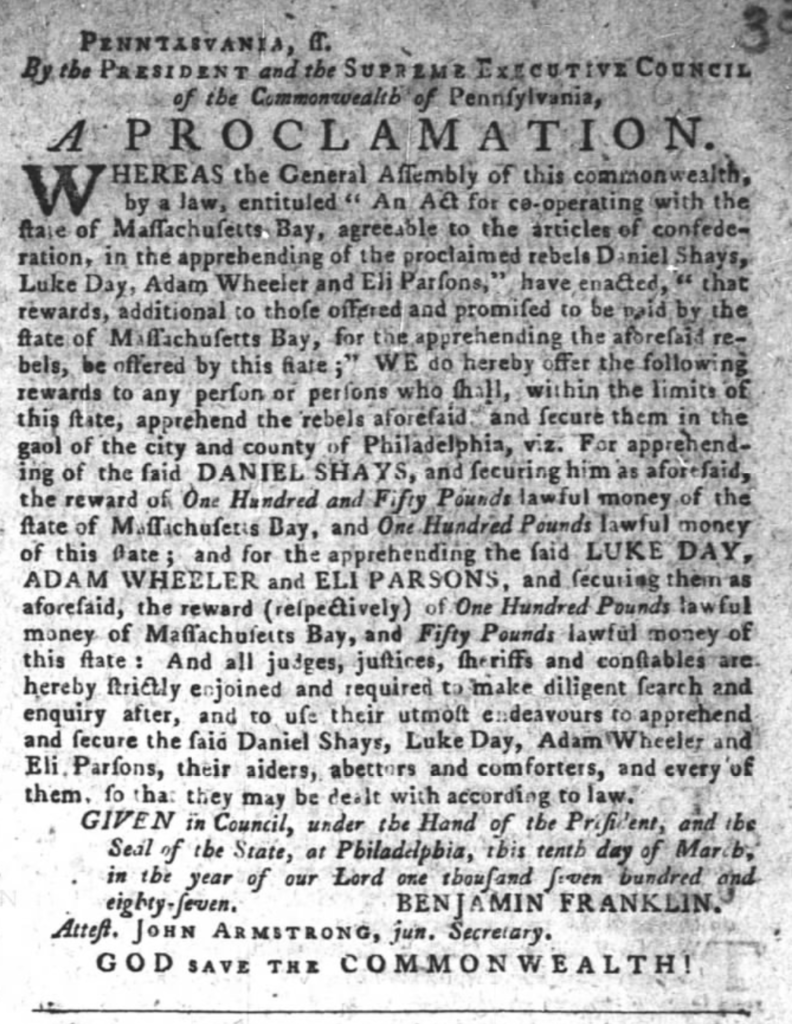

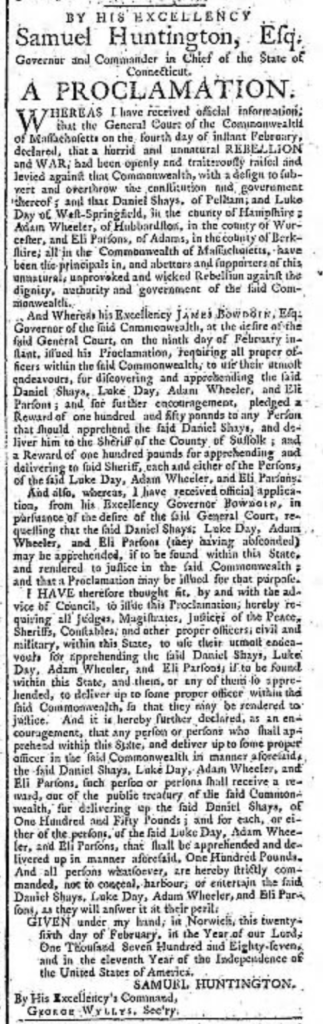

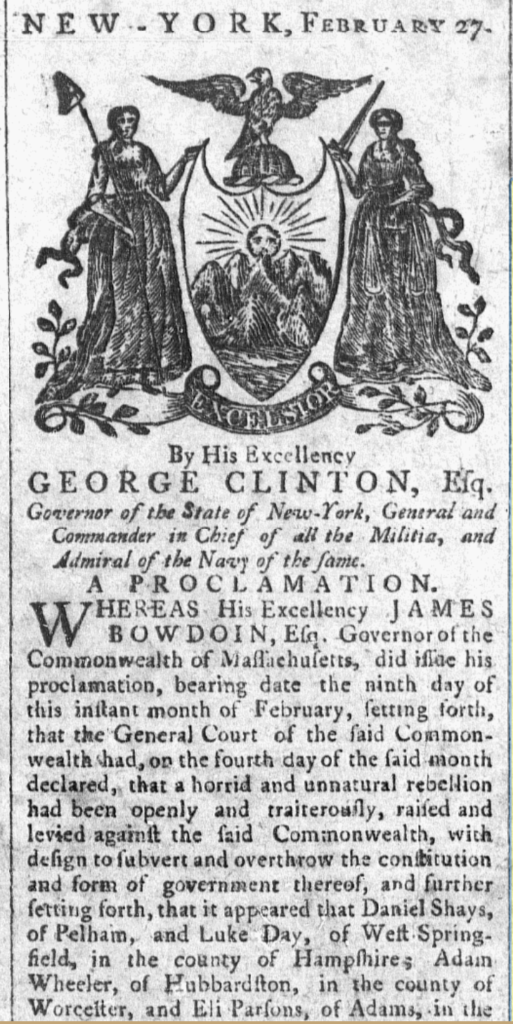

Rewards for Shays, Day, Wheeler and Parsons

On February 9, 1787, Governor Bowdoin issued a proclamation with a substantial reward of £150 for the apprehension of Daniel Shays. Rewards of £100 were also offered for Luke Day, Adam Wheeler, and Eli Parsons. Click here for a link to the Legislature’s Resolves of 1787.

Governors of neighboring states were asked to assist in the apprehension of insurgents who had fled Massachusetts. Copied below are examples of proclamations that were published by the governors of Pennsylvania (Ben Franklin), Connecticut and New York. While professing to provide assistance, New York and Vermont did little to help apprehend Shays and other insurgents who were effectively offered asylum in many sympathetic farming communities.

The reward for Shays’ arrest traveled far and wide, and was even reported in the London papers.

Hindsight?

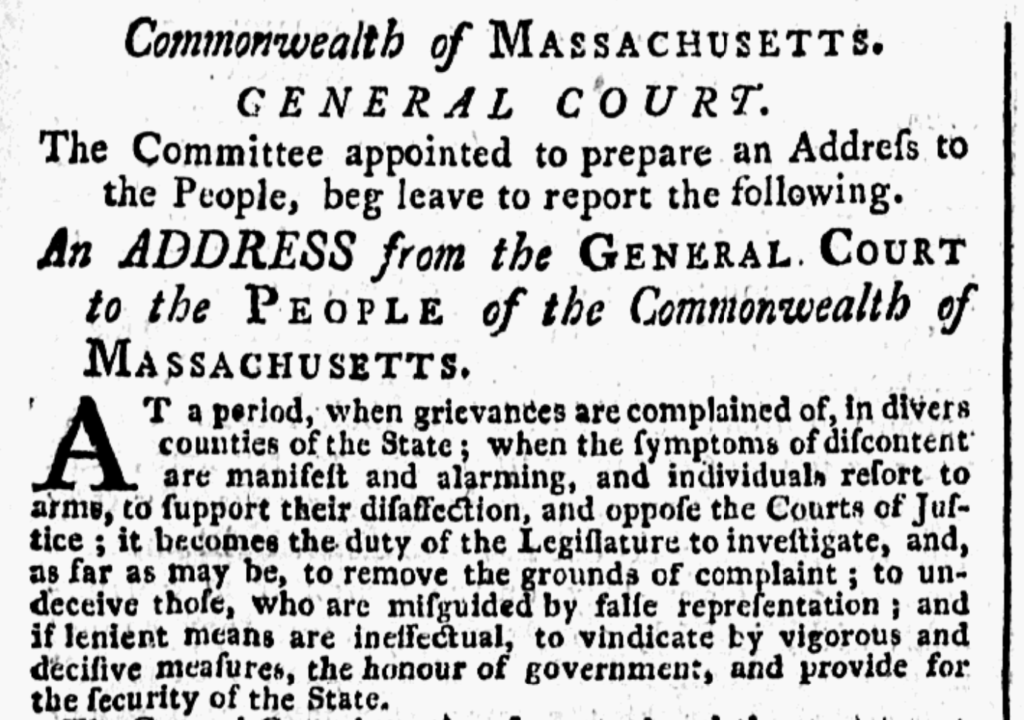

In a lengthy “Address to the People” following the special session in 1786, the Legislature attempted to justify and explain its actions. According to the Legislature’s public relation’s efforts, the new taxes were necessary to extinguish war debt, while private debts were the “ruinous effects of luxury and licentiousness.” The Address reasoned that the Legislature was attempting to accommodate grievances without undermining public credit and authority.

The Legislature also made a concerted effort to refute the suggestion that insurgents had a rightful claim to represent the will of the people. According to the Legislature, “in republican government the major part must govern. . . if every one opposes at his pleasure, it is no government, it is anarchy and confusion”:

Some persons have artfully affected to make a distinction between the government and people, as though their interests were different and even opposite; but we presume, the good sense of our constituents will discern the deceit and falsity of those insinuations. Within a few months the authority delegated to us will cease, and all the citizens will be equally candidates in a future election; we are therefore no more interested to preserve the constitution and support the government, than others: but while the authority given us continues, we are bound to exercise it for the benefit of our constituents. And we now call upon persons of all ranks and characters to exert themselves for the public safety.

In the spring elections, Bowdoin was defeated by the more accommodating John Hancock. Perhaps it can be said that the process worked when the newly elected Legislature suspended direct taxes for 1787 and introduced many reforms which had been sought by the protestors in 1786. Following Bowdoin and his party’s electoral defeat one newspaper asked whether “sedition itself [can] make laws.”

After submitting a petition, Daniel Shays was pardoned in 1788. He would receive a federal pension years later, but was never was able to reclaim a ceremonial sword that he was forced to sell to pay creditors prior to the Rebellion. The sword had been awarded to Shays – a veteran of the battles at Lexington, Bunker Hill and Saratoga – by the Marquis de Lafayette.

Over the years, historians have debated whether the – at best – modest efforts by the Massachusetts Legislature in the fall of 1786 stuck the right balance. John Adams’ predictions about the “turbulence in New England” in November of 1786 would be proven correct:

The Massachusetts assembly had in its Zeal to get the better of their Debt, laid on a Tax, rather heavier than the People could bear. but all will be well, and this Commotion will terminate in additional Strength to Government.

No doubt, the timing of Shays’ Rebellion provided an opportunity for the founding generation to grapple with critical questions of social order and coercive power in a republic. Yet, the Whiskey Rebellion would present similar questions less than a decade later. Click here for a discussion of the Whiskey Tax of 1791 and the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794.

Additional Reading:

Shays’s Rebellion: Authority and Distress in Post-Revolutionary America, Sean Condon (2015)

Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle, Leonard Richards (2002)

Shays’ Rebellion: The Making of an Agrarian Insurrection, David Szatmary (1980)

Acts and Resolves passed by the General Court (1893 republication)