Newly discovered letter fleshes out the difficulties facing the Maryland delegation at the Constitutional Convention

“There is no money in the Treasury”: Maryland Governor Smallwood’s reply to delegate John Francis Mercer

In 1911 Yale Professor Max Farrand published his seminal three-volume work, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787. Farrand gathered together all available documentary materials relating to the adoption of the Constitution. At the time, the manuscripts, notes and other records which told the story of drafting of the Constitution were scattered in archives and private collections around the world. Much of the material had never been published. Farrand’s work has since become the authoritative cannon which is regularly cited by generations of historians, biographers and courts.

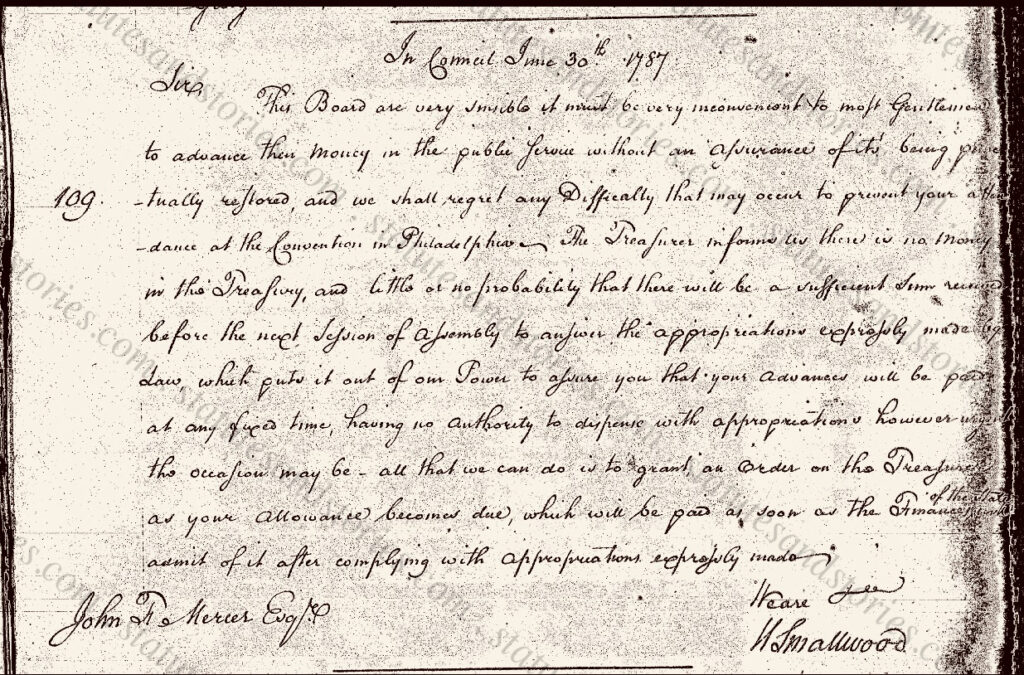

But Farrand did not find the following letter by Maryland Governor Smallwood to Convention delegate John Francis Mercer dated 30 June 1787. Smallword’s letter is pictured below. StatutesandStories.com is pleased to be the first to discuss and publish the text online. The letter was found in the Maryland State Archives in the letterbooks of the Governor and Council, which were microfilmed in 1949.

Governor Smallwood’s letter is significant because it alerts the Maryland delegation to the fact that there would potentially be a sizable delay before they received any funds to cover their expenses in Philadelphia. A pending post will discuss the 35 shillings per day of compensation eventually paid to the Maryland delegation. Click here for a comparison of delegation compensation paid by the states in 1787.

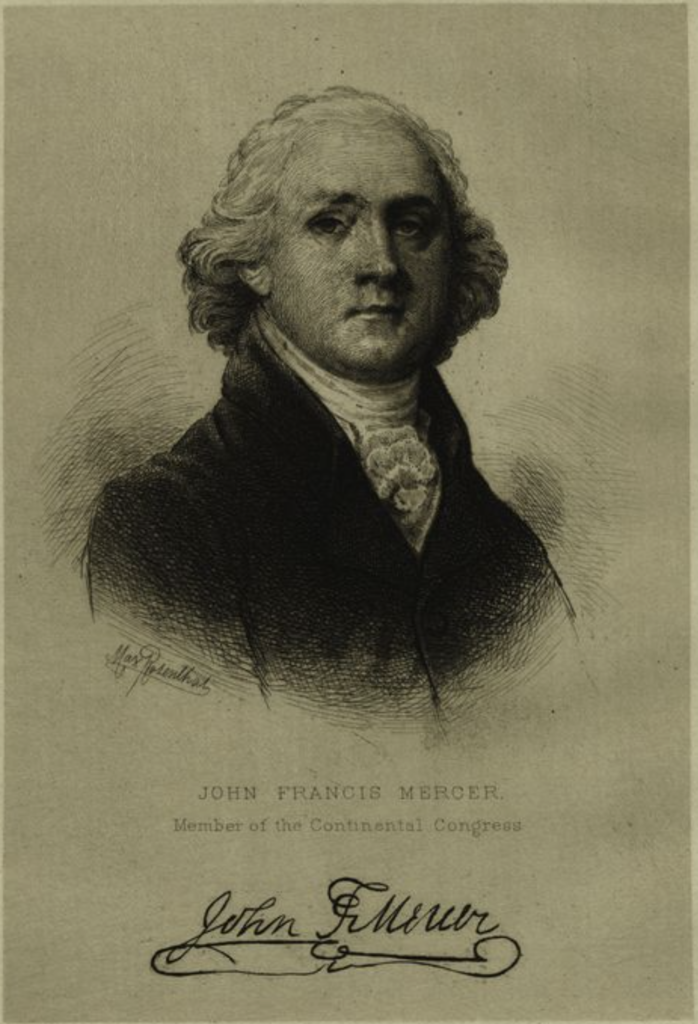

John Mercer was late to arrive in Philadelphia, first attending the Convention on August 6. He and fellow Maryland delegate Luther Martin did not agree with the direction that the Convention was heading. Mercer left the Convention less than two weeks later, on or about August 17. On September 4, fellow Maryland delegate, Luther Martin, would also depart without signing the Constitution. Mercer and Martin would become ardent Anti-Federalists who opposed ratification of the Constitution in 1788. Click here for materials related to the ratification of the Constitution in Maryland assembled by the Center for the Study of the American Constitution.

While the lack of funding is certainly not the only reason for Mercer’s departure, Governor Smallwood’s June 30 letter provides additional motivation for Mercer to leave Philadelphia in August. It also provides an explanation for why Mercer was so late to arrive.

Text of Governor Smallwood’s letter to delegate John Mercer

In Council June 30th 1787

To John Fr Mercer Esquire

Sir

This Board are very sensible it must be very inconvenient to most Gentlemen to advance their money in the public service without an assurance of its being punctually restored, and we shall regret any difficulty that may occur to prevent your attendance at the Convention in Philadelphia. The Treasurer informs us there is no money in the Treasury, and little or no probabilty that there will be a sufficient sum recevied before the next Session of the Assembly to answer the appropriations expressly made by Law, which puts it out of our Power to assure you that your advances will be paid at any fixed time, having no authority to dispense with appropriations however urgent the occassion may be – all that we can do is to grant an Order on the Treasury as your allowance becomes due, which will be paid as soon as the Finances of the State admit of it after complying with appropriations expressly made.

We are & ca.

W Smallwood

Pictured below is an image of John Francis Mercer. The portrait is available in the collections of the New York Public Library.

Text of letter from John Mercer to Governor Smallwood

In a letter dated 29 June 1787, John Mercer wrote to Governor Smallwood before leaving for the Convention. In his letter written from Annapolis, Mercer requested guidance as to when the Maryland delegates would receive payment. Among other things, Mercer points out that the requested advance “is usual in other states.” Mercer’s letter was published by James Hutson in 1987 and is copied below in its entirety to give context to Governor Smallwood’s reply pictured above:

Having been apprized by yr. Excellency, that difficulty had or would occur, to prevent the advance of money to those Gentlemen who have been appointed by the Legislature to attend the Convention now sitting in Philadelphia, no money having been appropriated to this purpose—I woud beg leave on this to remark to yr. Excellency, that such advances are, I am authorized to say usual in other States on this occasion & as far as it respects myself woud be now convenient—but as I fear that a cause of this nature may still have its future operation, I am led to be explicit with your Excellency on my part, that private circumstances do not permit my sparing any part of my own resources for any length of time, & that unless I coud receive assurance of a speedy restitution of my expences to the amount of the allowance the State has affixed, it will be wholly out of my power to attend—In making this communication, I hope your Excellency will remain persuaded, that I strongly regret the necessity, which obliges me on an occasion of this moment to suggest any difficulty of this nature.

Washington’s 9 September 1787 to Mercer

Mercer was one of the youngest delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Coincidentally, he owed money to George Washington, which debt obligation Mercer inherited as part of his father’s estate. In a famous letter dated 9 September 1787, Washington explained to Mercer that he would not accept slaves as payment of the debt.

According to Washington:

. . . I never mean (unless some particular circumstances should compel me to it) to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by the legislature by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptable degrees.

As described in the Washington papers, George Washington ultimately agreed to accept military certificates in payment of debt owed by the Mercer estate. Click here for Washington’s 1 Feb 1787 letter to John Francis Mercer. For the estate debt, see Washington to John Francis Mercer, 8 July 1784, n.1. Mercer would subsequently become Governor of Maryland in 1801. One of Mercer’s daughters, Margaret Mercer, became an abolitionist and freed all the slaves she inherited on her father’s death. When George Washington died in 1799, his will provided for the emancipation of all of the 123 slaves he owned, upon Martha’s death.

Background: Max Farrand’s Records of the Federal Convention of 1787

As described by Max Farrand, at the close of the Constitutional Convention, Secretary William Jackson delivered all of the Convention’s records to George Washington, the president of the Convention. At the end of his second term as President of the United States, Washington delivered these records to the Department of State in 1796. Two decades later, in 1818, Congress requested that the Convention records be printed. Appropriately, the publication was supervised by Secretary of State John Q. Adams. Yet, the official records passed down by Washington and published by JQ Adams are only a fraction of the records necessary to tell the full story of the framing of the Constitution.

American’s foundational documents complied a century later by Farrand include Madison’s detailed notes, Secretary Jackson’s official but limited Journal, assorted convention notes by Robert Yates, Alexander Hamilton, Rufus King, William Pierce, William Paterson, competing constitutional plans and drafts, and an array of correspondence and other materials written by the founders pertaining to the Constitution.

For the anniversary of the bicentennial of the Constitution in 1987, James Hutson and Leonard Rapport updated Farrand’s work by publishing The Supplement to Max Farrand’s The Records of the Federal Convention. Hutson was the long-serving chief of the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Rapport was a legendary archivist with the National Archives. Their Supplement added an assortment of “new” materials discovered since 1911, including George Washington’s diary, John Lansing’s notes on debates, and hundreds of pages of other primary sources.

Additional discoveries on StatutesandStories.com

Since the Covid-19 pandemic began in 2020, StatutesandStories.com has been pleased to publish several important archival records which are not contained in Farrand or Hudson. While the pandemic temporarily shut the doors to many state archives, archivists and staff continued to work behind the scenes to answer inquiries and otherwise assist researchers. For this assistance the author is grateful. Special thanks is also owed to my dear Professor John Kaminski of the Center for the Study of the American Constitution and Sergio Villavicencio of the Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society.

Among the “new” records discussed on StatutesandStories.com during the past several years are:

- Reimbursement records submitted by Alexander Hamilton to the State of New York for the Constitutional Convention

- Reimbursement records submitted by John Lansing to the State of New York for the Constitutional Convention

- Reimbursement records submitted by Robert Yates to the State of New York for the Constitutional Convention: “THE YATES RETURNS DISCOVERY”

- Reimbursement records submitted by Robert C. Livingston to the State of New York for travel to the Annapolis Convention

- Journals, ledgers and other records reflecting delegate compensation paid to Convention delegates including discoveries in New Hampshire and Virginia

- Evidence establishing that the Annapolis Convention could have obtained a quorum if it had wanted to wait longer for the pending arrival of more delegates: “THE ANNAPOLIS END THESIS”

- Evidence that Alexander Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia prior to May 18 and may have participated in deliberations with the Pennsylvania and Virginia delegations: “THE HAMILTON ARRIVAL THEORY”

- Evidence that John Lansing was suing Philip Schuyler in 1787

- Evidence that Alexander Hamilton was the author of the Constitution’s Cover Letter: “THE HAMILTON AUTHORSHIP THESIS”