Newly discovered financial records in the Massachusetts State Archives underscore the drama preceding the Constitutional Convention in 1787

Massachusetts delegate compensation – Part I

Beginning with the Boston Massacre in 1770 and the Boston Tea Party in 1773, Massachusetts became a focal point in the struggle for American independence. Famously, the first battle of the Revolutionary War was fought in Massachusetts when the “shot heard around the world” was fired at Lexington and Concord in 1775. While the “Spirit of 1776” arguably began in Boston, revolutionary ferment quickly spread to other colonies which rallied together in support of Massachusetts. A decade later, Massachusetts not surprisingly played a leading role in the drafting of the Constitution. Yet, the financial records of the Massachusetts delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787 have never been compiled and systematically studied.

Recently uncovered financial records and journals in the Massachusetts State Archives shed new light on the Massachusetts delegation and the behind-the-scenes drama in Philadelphia in 1787. These records reveal that in the days leading up to the Constitutional Convention, Massachusetts was simply unable to timely pay its delegates their promised £100 advance. The state had recently borrowed to raise a private army to suppress Shays’ Rebellion. Massachusetts was also forced to borrow to underwrite the cost of ongoing state operations. To pay its delegates, Massachusetts would need to reallocate funds, as there were “none in the treasury.”

StatutesandStories.com owes a debt of gratitude to Caitlin Jones, the Head of Reference at the Massachusetts State Archives. Working with Caitlin to assemble these overlooked archival records, StautesandStories is pleased to tell the story of Massachusetts’ struggle to compensate its delegates during the summer of 1787. As set forth below, the following insights can be drawn from these newly revealed records which help complete the historic record of the Convention:

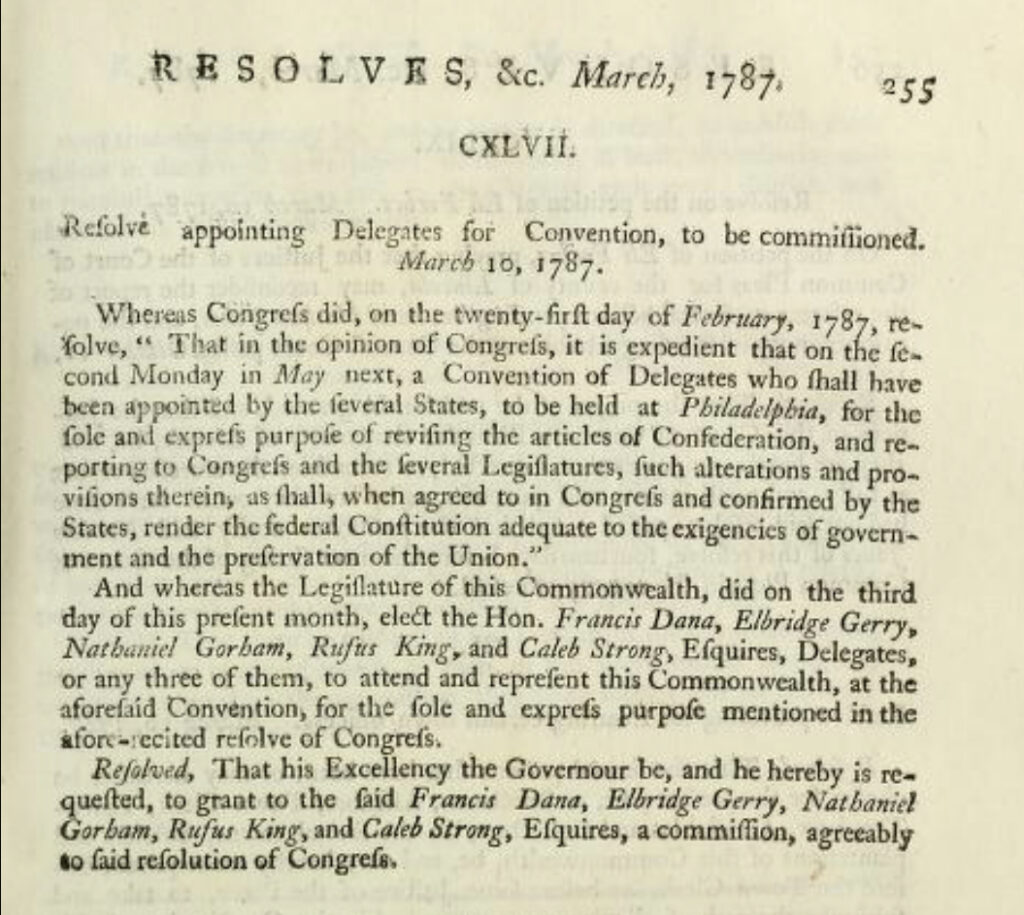

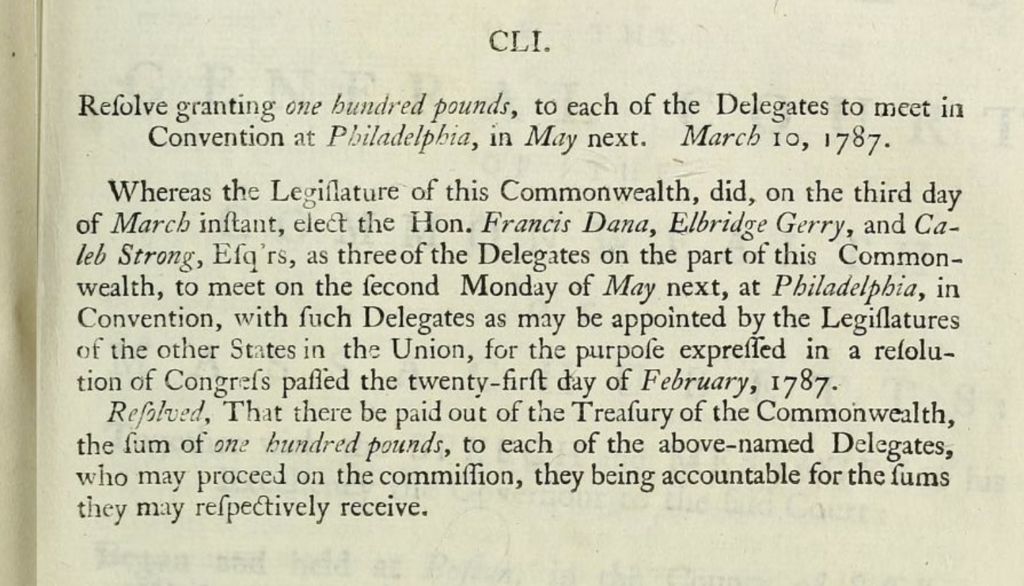

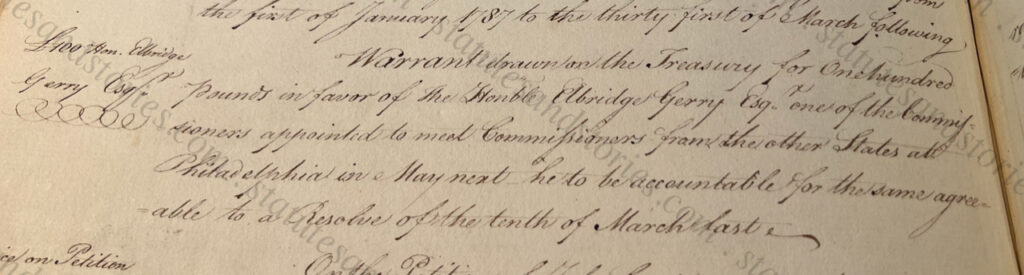

- Commitment to pay £100 pounds: When Massachusetts appointed its five delegates on 10 March 1787, the legislature committed that it would pay £100 pounds each to Francis Dana, Elbridge Gerry, and Caleb Strong.

- Separate treatment for members of Congress: The two remaining delegates, Rufus King and Nathan Gorham, were sitting members of Congress. As such, they were excluded from the £100 advance. Nevertheless, King and Gorham were entitled to compensation as members of Congress.

- Explicit commitment in advance of the Convention: By contrast, several other states did not make any explicit commitments to pay their delegates in advance of the Convention, as Massachusetts aspired to do.

- Delay: Predictably, due to the state’s poor finances, there were delays in paying the Massachusetts delegates. Moreover, King and Gorham were already owed several hundred pounds of unpaid Congressional compensation. The lump sum payment of arrearages to King and Gorham in 1787 would enable them to cover their expenses in Philadelphia.

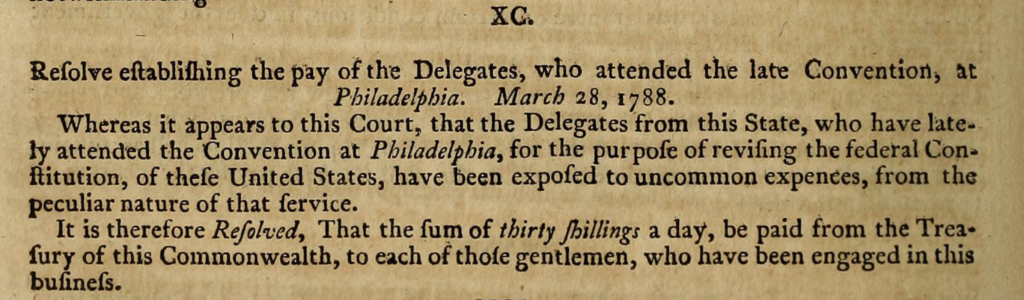

- Subsequent agreement to pay 30 shillings per day: Following the Convention, Massachusetts recognized that its delegates had been “exposed to uncommon expenses, from the peculiar nature of that service.” By Resolution 90 adopted on 28 March 1788, Massachusetts agreed to reimburse its delegates 30 shillings a day for their attendance in Philadelphia.

- Caleb Strong attendance dates: Based on the information provided by Caleb Strong in his request for reimbursement, it is now possible to pinpoint the exact dates of his attendance/travel to the Convention: May 22 to August 25. Based on the final reimbursements paid in 1788, Caleb Strong received a total of £144 for 96 days of attendance/travel.

- Elbridge Gerry attendance: Based on the final reimbursements paid in 1788, it is also possible to reconstruct that Elbridge Gerry received a total £196.5, corresponding to 131 days of attendance/travel.

- Preservation of quorum: While it is impossible to know for certain, it is likely that Massachusetts’ explicit legislative commitment on March 10, 1787 to pay its delegates contributed to the retention of a quorum. Importantly, three members of the Massachusetts delegation were present on the final day of the Convention, September 17.

- Gerry’s decision to stay: Elbridge Gerry, who refused to sign the Constitution on September 17, may also have been motivated to remain in Philadelphia by the legislature’s explicit requirement that three members were necessary for a functional delegation. By comparison, “dissenting” delegates from New York and Maryland simply departed the Convention.

This blog post (Massachusetts delegate compensation – Part I) is the continuation of a multi-part series discussing delegate compensation and expenses during the summer of 1787. The discussion of Massachusetts delegate compensation in Part I continues with a supplemental blog post, Massachusetts Delegate Compensation – Part II (pending). Part II will provide dozens of newly located images of Massachusetts financial records, along with legislation and other primary sources. For a comparison of delegation compensation across the states click here. The following links provide detailed discussions of recent discoveries involving delegate compensation paid by New York, Virginia, and New Hampshire.

Massachusetts Resolves appointing delegates and providing compensation

By resolution adopted on March 10, 1787 (Resolve 147), Massachusetts selected five delegates to attend the Constitutional Convention: Francis Dana, Elbridge Gerry, Caleb Strong, Rufus King and Nathan Gorham. On the same day that Massachusetts selected its five delegates, it adopted a second resolution (Resolve 151) granting £100 to Dana, Gerry and Strong. Because King and Gorham were members of Congress, their names were omitted from the second resolution. Presumably, this was because King and Gorham were otherwise entitled to their customary Congressional compensation. Both resolves are pictured below.

After the Constitutional Convention, beginning in December of 1787, five states quickly ratified the Constitution. Nevertheless, the Constitution faced its first true test in Massachusetts, the home of Anti-Federalist Sam Adams. Based on the so-called “Massachusetts compromise,” the Massachusetts Federalists agreed to support a Bill of Rights. As a result, on 6 February 1788 Massachusetts became the sixth state to ratify, by a narrow vote of 187 to 168.

Copied below is Resolve 90, adopted on 28 March 1788. By enacting Resolve 90 Massachusetts agreed – after the fact – to reimburse its delegates 30 shillings per day for their time in Philadelphia. Thus far, Gerry and Strong had only been paid £100 each for their months of service the prior year. Because King and Gorham were members of Congress, they had not yet received any additional reimbursement, apart from their Congressional pay.

Convention payments to Gerry and Strong

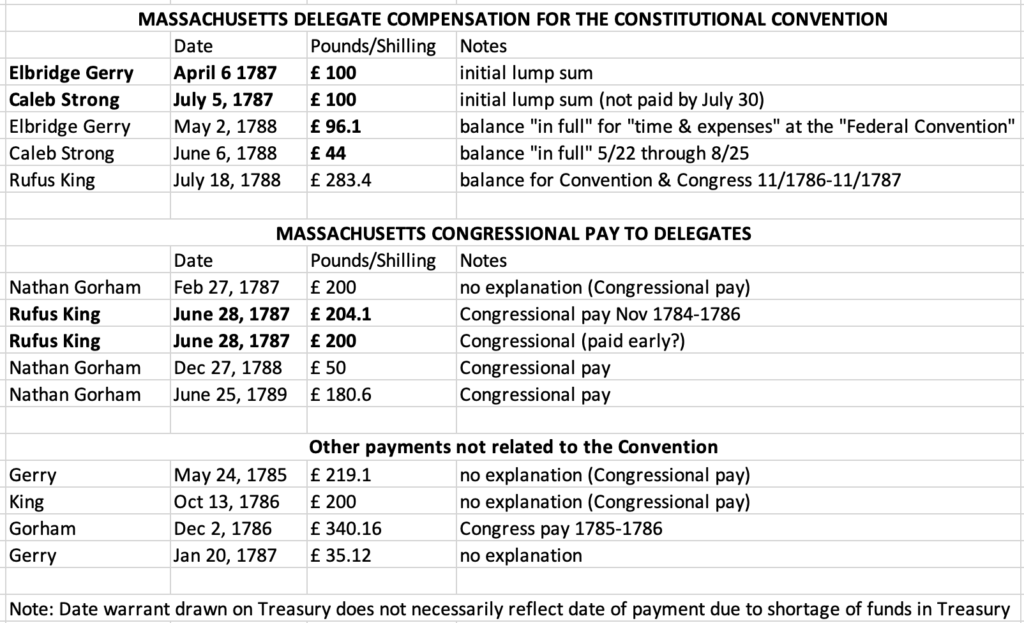

By compiling together financial records relating to the Convention, it is now possible to reconstruct for the first time the total compensation paid to the Massachusetts delegates. As illustrated by the following chart, Elbridge Gerry was paid a total of £196.5 for 131 days of attendance. Caleb Strong received a total of £144 pounds for 96 days of attendance. Because Rufus King and Nathan Gorham were members of Congress, it is more difficult to parse out their Convention pay from their Congressional pay.

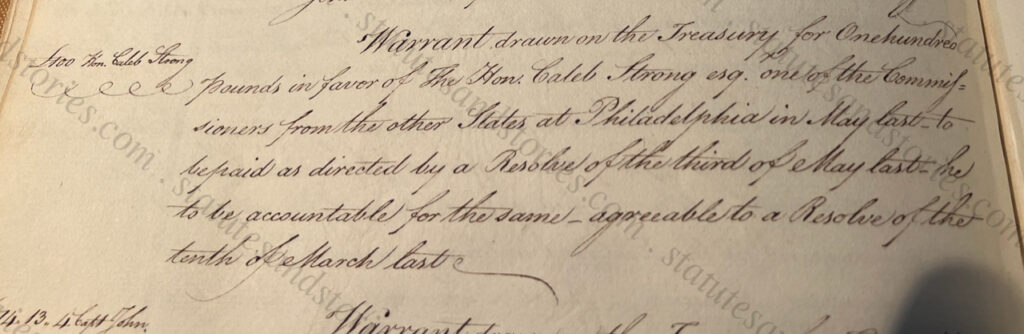

Pictured below are the financial ledgers evidencing the initial £100 warrants issued to Gerry on April 6 and Strong on July 5, 1787. Subsequently, in 1788, catch-up amounts of 30 shillings per day were paid pursuant to Resolve 90. Gerry was paid £96.5 pounds on May 2, 1788. Strong was paid £44 pounds on June 6, 1788. Images of the 1788 catch-up payments, along with other records, are available in Part II (pending).

According to James Madison’s notes, Caleb Strong arrived at the Convention on May 28. It is thus unclear why Strong’s warrant was not drawn until July 5th. One possibility is that Strong knew that there were no funds in the Treasury when he departed Boston in May.

To celebrate the July 4th holiday, the Convention took a two-day recess on July 3 and July 4th. It is thus possible, but unlikely, that Strong used this opportunity to travel back to Boston to seek payment. Or, subsequent research may confirm that the July 5th warrant was subsequently delivered to Caleb Strong in Philadelphia. For reasons which are discussed below, the date of issuance of a warrant does not necessarily correspond with the date that the warrant was received by the delegate, or the date cashed.

Based on James Madison’s notes, it is clear that Strong was in attendance at the Convention on July 2. Strong does not reappear in Madison’s notes, however, until July 14. Thus, it is possible (but unlikely) that Strong took an extended recess for the July 4th holiday. Because the other three Massachusetts delegates were present on July 5th, the state would have still preserved a three-member quorum in Strong’s absence. Stay tuned as StatutesandStories cross references primary sources and delegate notes, along with other financial journals in the Massachusetts State Archives. Historians and researchers are invited to weigh into this question, raised by Strong’s July 5th warrant.

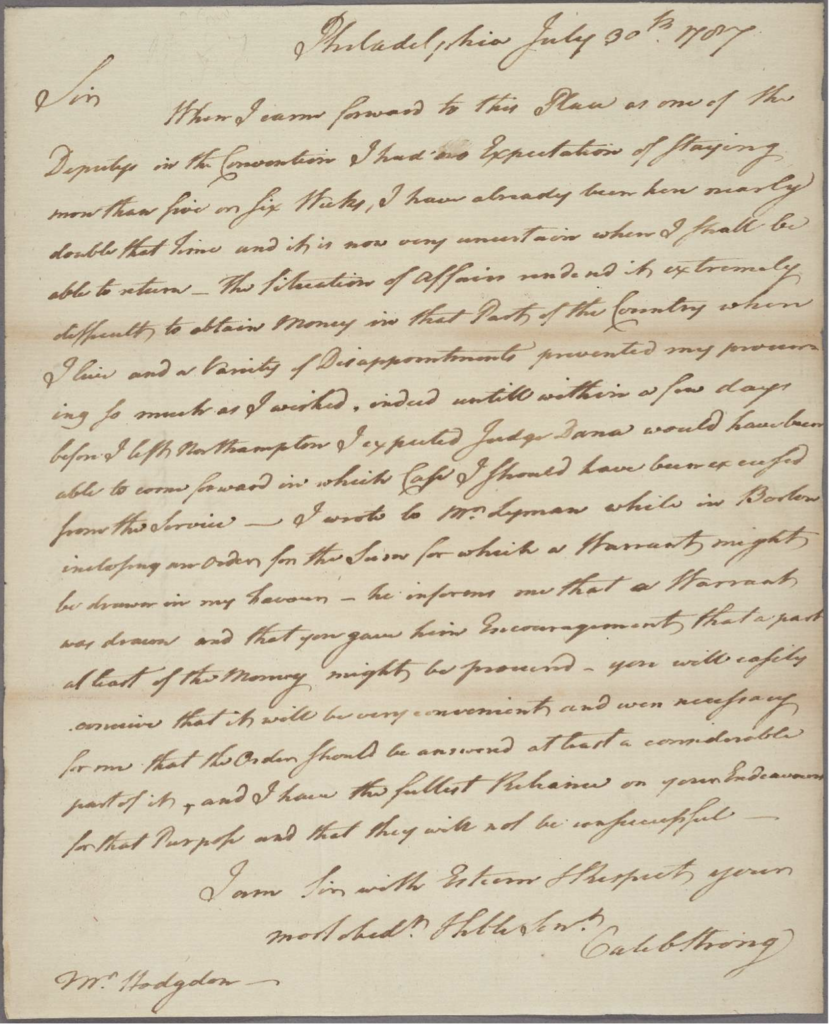

On July 30th Caleb Strong wrote to Massachusetts Treasurer, Alexander Hodgden, following up and requesting payment:

Sir When I came forward to this Place as one of the Deputys in the Convention I had no Expectation of staying more than five or six Weeks. I have already been here nearly double that Time and it is now very uncertain when I shall be able to return. The Situation of Affairs renderd it extremely difficult to obtain Money in the Part of the Country where I live and a Variety of Disappointments prevented my procuring so much as I wished. Indeed untill within a few days before I left Northampton I expected Judge Dana would have been able to come forward in which Case I should have been excused from the Service. I wrote to Mr. Lyman while in Boston inclosing an Order for the Sum for which a Warrant might be drawn in my Favour. He informs me that a Warrant was drawn and that you gave him Encouragement that part at least of the Money might be procured. You will easily conceive that it will be very convenient and even necessary for me that the Order should be answered at least a considerable part of it and I have the fullest Reliance on your Endeavors for that Purpose and that they will not be unsuccessful.

While a warrant was issued to Strong on or about July 5th, Strong’s letter indicates that by July 30 he still had not been able to “procure” payment. An image of Strong’s July 30 letter (held at the New York Public Library) is copied below:

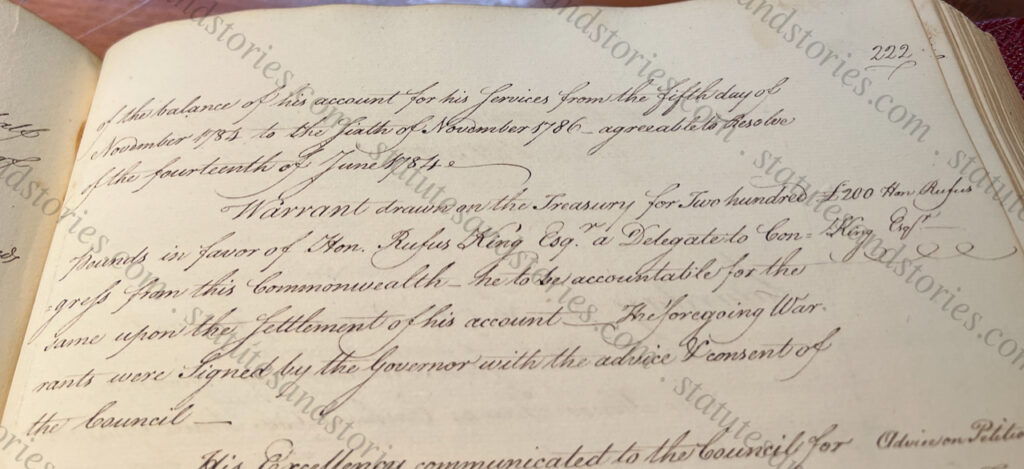

Convention payments to King

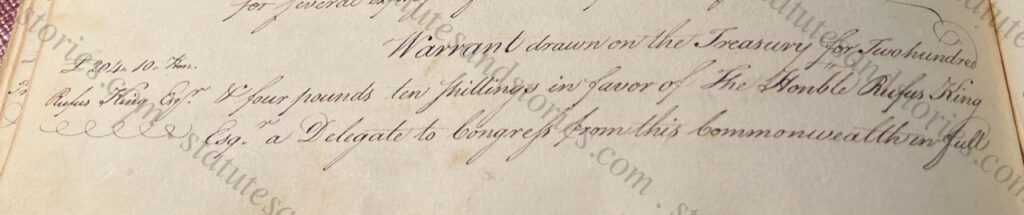

The picture is even more complex for Congressional delegates Rufus King and Nathan Gorham. Both King and Gorham were sitting members of Congress in 1787. Further complicating King’s payments, was the fact that he was owed money for prior service in Congress.

Interestingly, during the Convention two warrants were issued to Rufus King on 28 June 1787, for a total of £404.5. The first of these payments, in the amount of £204.5 (a pound is equivalent to 20 shillings and thus .5 pounds = 10 shillings), was for Congressional pay from 5 November 1784 to 6 November of 1786. The second June 28th warrant, in the amount of £200, simply provides that the payment was in favor of Rufus King as “a Delegate to Congress.” It is reasonable to deduce that this £200 payment was for King’s current Congressional term. The two June warrants totaled £404.5. As described below, this sum was in fact more than King was requesting, but was presumably helpful to fund King’s activities in Philadelphia.

Useful context for these two warrants is provided by a letter dated 24 June 1787 from Rufus King to Massachusetts Treasurer, Alexander Hodgden. In his letter written from Philadelphia, King cites to his “heavy expenses” at the Constitutional Convention. King requests payment of £200, which was seemingly authorized four days later, on June 28th:

Sir You must be sensible from the state of my account with the Treasury that I have a much larger demand for arrears of pay than either of my colleagues. I have made it a rule to forbear my importunities on this subject as long as possible. My present situation exposes me to heavy expenses, and I cannot but think that you will unite with me in Opinion that my claims are not behind those of any person who has a Demand on the Treasury. I took an order some months since, on a note of the tax Treasurer’s, for 100£. I sold it for 90£. I cannot think of suffering so great a loss of my wages in future. I pray you to inform me when you will authorize me to draw on you for 200£. A much larger sum is due to me but I shall be content to wait some Time for the balance.

Accordingly, it appears that King’s June 24 letter triggered the two warrants dated June 28th. The following month, on July 30th, Caleb Strong wrote his own letter to Treasurer Hodgden, similarly requesting payment.

After ratification – July of 1788 – King would receive additional compensation for “his services to the Federal Convention in Philadelphia” and for the “balance of his account as a delegate to Congress from the seventh of November 1786 to the fifth of November 1787.”

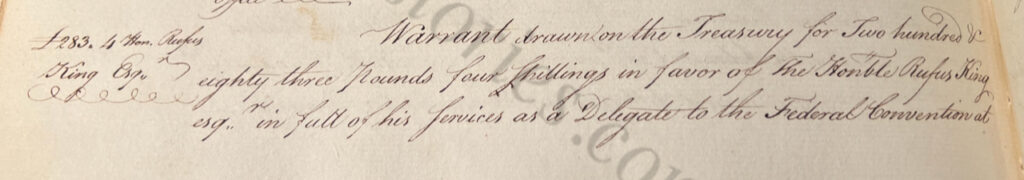

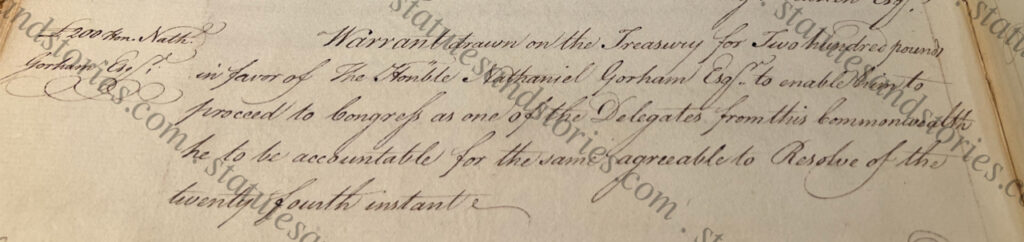

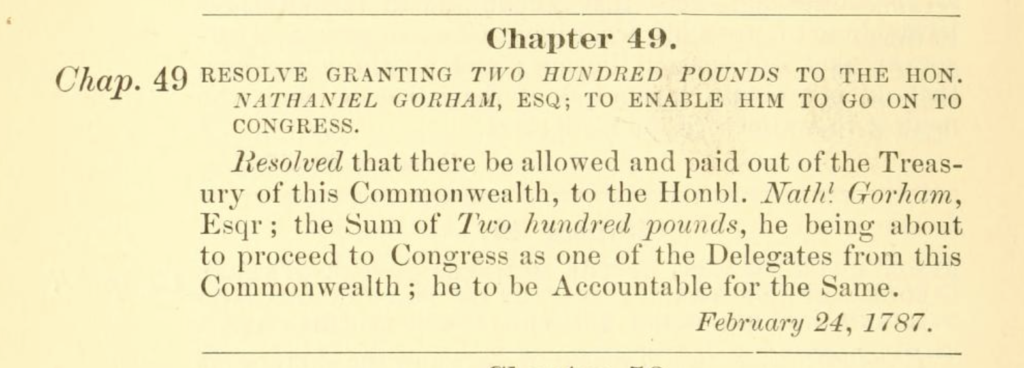

Convention payments to Gorham

Nathan Gorham had been serving in Congress since 1785 when he was appointed as a delegate to Philadelphia. On 27 February 1787 Gorham was paid £200, which almost certainly was an advance of his Congressional pay for the current term. Indeed, on February 24 the legislature adopted a resolution (Chapter 49) specifically granting two hundred pounds to enable Gorham “to proceed to Congress” as one of Massachusetts’ delegates.

Unlike Rufus King who “made it a rule to forbear my importunities on this subject as long as possible,” Gorham was more current collecting his Congressional pay from Massachusetts. In December 1786, Gorham was paid £340 and 16 shilling for his service from 29 December 1785 to 25 November 1786.

Gorham would receive another £50 in December of 1788. In June of 1789 he was paid £180 and 6 shillings. Further research will be required to confirm whether the £50 payment in 1788 was related to the Convention (and the 30 shilling per diem approved in March of 1788).

A chart of all payments to the Massachusetts delegates from 1785 through 1789 is copied below. Images for these payments will be presented in Part II (pending).

Massachusetts delegates

Although their names were listed alphabetically in Resolve 147, Nathan Gorham was the senior member of the Massachusetts delegation. At the time of his appointment to the Constitutional Convention, Nathan Gorham had recently presided as the “President” of Congress in 1786. Having previously served in Congress from 1782 to 1783, Gorham was reappointed to serve from 1785 through 1787. Click here for the dates of service in the Continental and Confederation Congress.

While Rufus King was the youngest member of the Massachusetts delegation to Philadelphia, he was also an experienced member of Congress. King began representing Massachusetts in 1784 and was an incumbent member of Congress when appointed in 1787 to represent Massachusetts at the Constitutional Convention.

Elbridge Gerry was also a seasoned politician, having served in the Confederation Congress from 1783 to 1785. Gerry likewise served in the Continental Congress from 1776 to 1780. As a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation, Gerry may be the most famous member of the Massachusetts delegation. Gerry would later be elected as the 5th Vice President of the United States under President Madison. As described below, although the unpredictable Gerry refused to sign the Constitution, he remained in Philadelphia respectful of the three-member quorum requirement to preserve a functional delegation from Massachusetts.

Caleb Strong was a successful lawyer who assisted with the drafting of the Massachusetts Constitution. He turned down a position on the Massachusetts Supreme Court due to the “inadequate” salary. While he lacked Congressional experience in 1787, Strong served in the Massachusetts legislature. He would subsequently be elected to the inaugural United States Senate. Strong would also serve two terms as Governor of Massachusetts. Strong departed the Convention early, likely because of the poor health of his wife.

Likely due to ill health and the press of judicial business, Francis Dana was unable to attend the Convention. Dana was imminently qualified as a sitting justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Court (1785-1791) and as a signer of the Articles of Confederation. Dana subsequently served as Chief Justice from 1791 to 1806.

Massachusetts background

According to historian Clinton Rossiter, “[t]he most remarkable feature of the delegation from proud Massachusetts was the absence of most of her justly famous sons.” At the time of the Convention John Adams was serving as the American ambassador to England. Moreover, none of the following prominent Massachusetts leaders were selected as delegates: Sam Adams, Henry Knox, James Warren, Governor Bowdoin, soon-to-be-elected Governor John Hancock, or Massachusetts Supreme Court Chief Justice William Cushing.

As Rossiter explains, as “[o]ne of the world’s two most productive nurseries of able politicians and lawyers, Massachusetts was the only state in the Union that could have squandered its resources so carelessly and still produced a respectable delegation.”

Nevertheless, the four Massachusetts delegates who attended the Convention made important contributions. For example, Gorham served as the Chair of the Committee of the Whole and Gerry chaired the Committee on Representation which proposed the Connecticut Compromise. Rufus King served on six committees, including the Committee on Style and Arrangement which prepared the final draft of the Constitution.

In Rossiter’s estimation, only five states including Massachusetts were responsible for the lion’s share of the “thoughts, decisions, and inventive moments” that went into the Constitution. No doubt the unrest resulting from Shays’ Rebellion helped crystalize thinking in Massachusetts. As described by historian John Kaminski, “Shays’s Rebellion had an enormous impact on the attitudes of many men in Massachusetts and throughout America. Men such as Rufus King and Elbridge Gerry who had previously opposed the calling of a constitutional convention, now advocated one.” For a discussion of Shays’ Rebellion and the laws which precipitated it click here and here.

This post will continue in Part 2 (pending) which will provide a variety of images of financial records evidencing payments to Massachusetts delegates. In addition, Part 2 will present a variety of primary sources illustrating the concerns in Massachusetts leading into the Constitutional Convention.

Additional Reading and Sources:

Kaminski et al, Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Massachusetts (1997)

Catherine Drinker Bowen, Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention (1966)

1787: The day-to-day story of the Constitutional Convention (1987)

Christopher and James Lincoln Collier, Decision in Philadelphia (2007)

David O. Stewart, The Summer of 1787: The Men who Invented the Constitution (2007)

Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (2009)

Clinton Rossiter, 1787: The Grand Convention (1987)