Newly discovered records of payments to New Hampshire delegates John Langdon and Nicholas Gilman

After more than two hundred and thirty years, newly uncovered records in the New Hampshire State Archives shed light on a mystery which is as old as the Constitution. Working with New Hampshire’s Acting State Archivist, Brian Burford, we are now able to fill in some of the details about how and when New Hampshire delegates John Langdon and Nicholas Gilman were paid for their work drafting the Constitution in 1787.

Signatures on the Constitution and New Hampshire late arrival

When the delegates in Philadelphia lined up to sign their names to the Constitution on September 17, 1787, John Langdon and Nicholas Gilman of New Hampshire were likely at the very front of the line. In fact, they may have been the first to sign the Constitution. Since the states were grouped geographically from north to south, New Hampshire was at the top of the list of states.

George Washington’s name is the first to appear, since he signed the Constitution as the President of the Convention. Langdon and Gilman’s names appear immediately below George Washington, in the first column of signatures on the bottom right of the fourth page of the Constitution. Before the delegates signed, Alexander Hamilton carefully wrote the names of the twelve states in attendance, excluding Rhode Island, which didn’t send delegates to Philadelphia. The delegates then proceeded to sign alongside the name of their respective state.

Although Langdon and Gilman may have been the first to sign the Constitution, they were late to arrive in Philadelphia. While the Convention was scheduled to convene on May 14, official business did not begin until May 25, when a quorum of seven states was present.

Langdon and Gilman finally arrived two months later, on or about July 23. Coincidentally, the same day of their arrival, William Patterson departed to return home to New Jersey. Patterson, the author of the so-called New Jersey Plan, would return on September 17th to sign the Constitution along with a total of 39 signers.

Despite their delayed arrival in late July, Langdon and Gilman were not to blame. As described in the book Decision in Philadelphia, it was thanks to Langdon that they arrived at all:

[F]or when the parochial New Hampshire legislature, suspicious of what was going on in Philadelphia, refused week after week to allocate their delegates the expenses for the trip, Langdon decided to pay the expenses for himself and his fellow delegate, Nicholas Gilman.

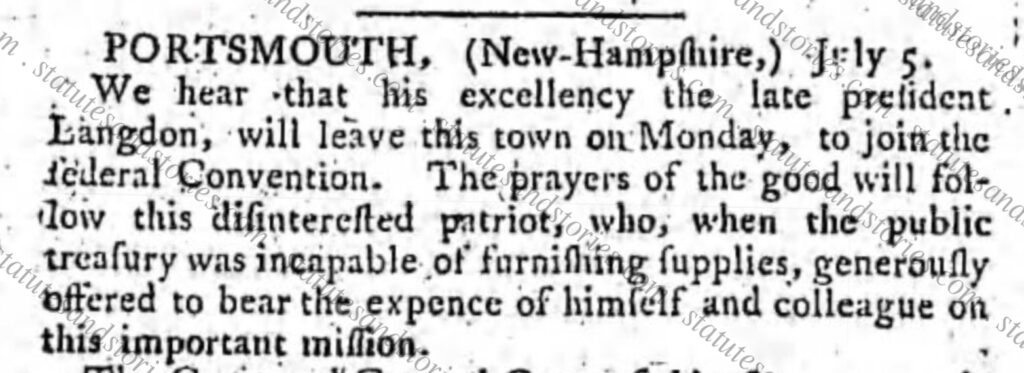

Pictured below is a widely reprinted newspaper report that John Langdon and Nicholas Gilman would be leaving for Philadelphia in early July, 1787 to join the “federal Convention.” As reported out of Portsmouth, the “prayers of the good” should follow this “disinterested patriot.” When the public treasury was empty, Langdon “generously offered to bear the expense of himself and colleague on this important mission.”

Prior scholarship

There is no shortage of books written about the drafting of the Constitution. Nevertheless, it does not appear that any historians were able to untangle the details of how and when Langdon and Gilman were finally paid for their work in Philadelphia.

New Hampshire was one of the first five states to appoint delegates in January of 1787. Yet, when the initial slate of delegates refused to serve the New Hampshire legislature was forced to select a new delegation in late June. Click here for a link to the Journal of the New Hampshire Senate on June 27.

The fact that Langdon stepped in to cover the costs has long been known. As described by Richard Beeman in the book Plain, Honest Men:

True to its unmatched record for parsimony in matters of government expense – a record that persists to this day – the New Hampshire legislature refused to pay the expenses of the delegates, with the result being that it took nearly another month for any of the elected to agree to serve. When Langdon and Gilman finally did show up – Pickering and West never made it – they did so because Langdon, a wealthy merchant from Portsmouth, had agreed to pay the delegation’s expenses himself.

Similarly, Catherine Drinker Bowen in her classic work, Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention recounts how New Hampshire’s delegation was delayed until Langdon stepped into the breach. By the time of their arrival the Great Compromise – also known as the Connecticut Compromise – had already been reached:

About a week after the Great Compromise was passed, the two New Hampshire delegates finally appeared – a good nine weeks late; the Convention knew they had waited until Governor Langdon offered to pay for the journey.

The book 1787: the day-to-day story of the Constitutional Convention was written in connection with the bicentennial of the Constitution by historians at the National Park Service. In a discussion of the cost of the Convention, the authors explain that eleven state delegations received “expense money” in some form, ranging from $4 per day (New Jersey) to 40 shillings per day (Delaware). Without citing any primary sources, the authors conclude that, “[s]ome of the states advanced expense money, others paid as soon as its delegates got home, and New Hampshire paid its delegates within a year.” The thrust of this statement is largely accurate. Set forth below is the rest of the story.

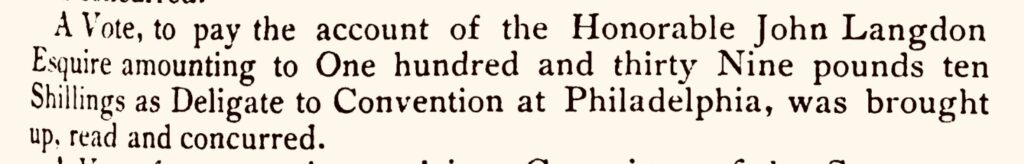

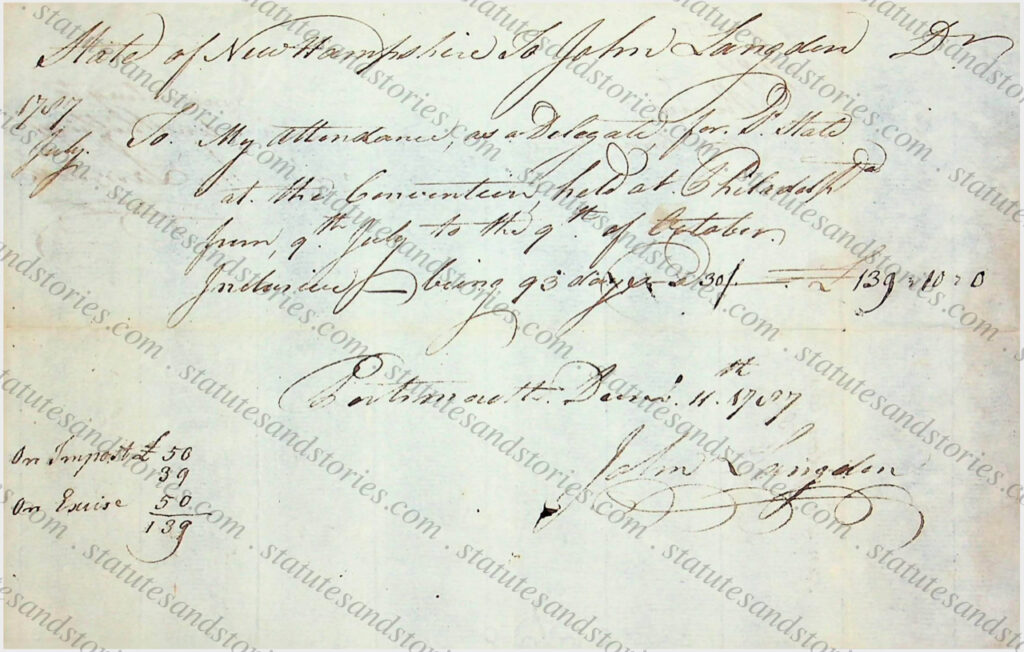

Newly identified proof of payment to Langdon

So how and when were Langdon and Gilman paid? The issue of why this matters is also discussed below. According to the Senate Journal, a vote was taken on December 12, 1787 to pay Langdon £139 and 10 shillings. The House Journal similarly records the vote on December 12 to pay Langdon £139 and 10 shillings “by order of the President [John Sullivan].” As the third governor of New Hampshire, Sullivan served his first term of office from June of 1786 to June 1788, as the “President” of New Hampshire, the official title at the time.

Nothing is mentioned, however, in the House or Senate Journals about how this £139 and 10 shillings sum was calculated. Moreover, it is unclear whether or not this amount reimbursed Langdon for the expenses he incurred when paying for Gilman’s costs.

Copied above is the entry in the Senate Journal, which is helpful but inconclusive. Pictured below is one of several newly revealed records which helps provide answers. This document was located by New Hampshire’s acting State Archivist, Brian Burford. As set forth above Langdon’s flowing signature – the same signature which is evident on the Constitution – is the following account by Langdon:

To my attendance, as a Delegate, . . . at the Convention, held at Philadelphia from 9th July to the 9th of October inclusive being 93 days at 30 shillings per day [equals] £139 and 10 shillings

Thus, taking the House and Senate Journals together with this record, it becomes clear that Langdon submitted his request for payment on December 11, 1787. Both houses of the New Hampshire legislature voted the following day, December 12, to pay Langdon the precise sum that he requested, £139 and 10 shillings.

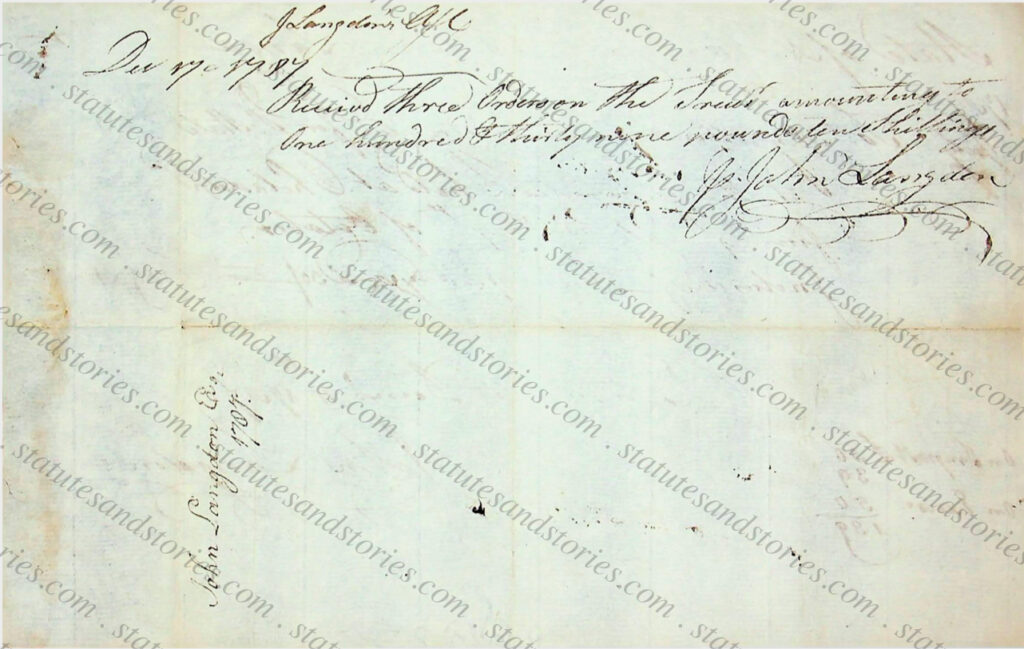

On the back of the page, Langdon signs alongside the notation that he received payment on December 17. While the ink is faint, Langdon was apparently paid with “three orders” amounting to the sum of £139 and 10 shillings.

It also becomes clear how the £139 and 10 shillings sum was calculated. Langdon indicates that he earned a per diem of 30 shillings per day, for 93 days (from July 9th to October 9th). Because there are 20 shillings in a pound, Langdon was owed a total of 2,793 shillings (30 x 93 = 2,793 / 20 = £139.5), which is equivalent to £139 and 10 shillings.

The bottom right notation on the receipt also identifies the sources from which this relatively large sum was to be paid. Fifty pounds would be paid from “excise” taxes with the balance (50 and 39 pounds) paid from “impost” taxes. By comparison, the annual salary of the Governor (President Sullivan) in 1784 was £200 pounds.

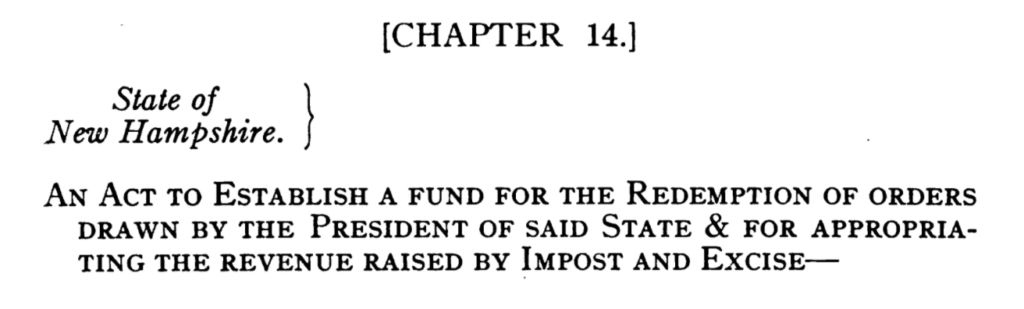

Copied above from the Laws of New Hampshire is the title of Chapter 14, “An Act to Establish a Fund for the Redemption of Orders Drawn by the President of Said State & For Appropriating The Revenue Raised by Impost and Excise.” The act was passed on September 28, 1787. In addition to providing for impost and excise duties, the act further provided that the revenue annually arising from these taxes was appropriated for the payment of salary for delegates to Congress, judges, and other state officials, including the New Hampshire President, Treasurer, and Attorney General.

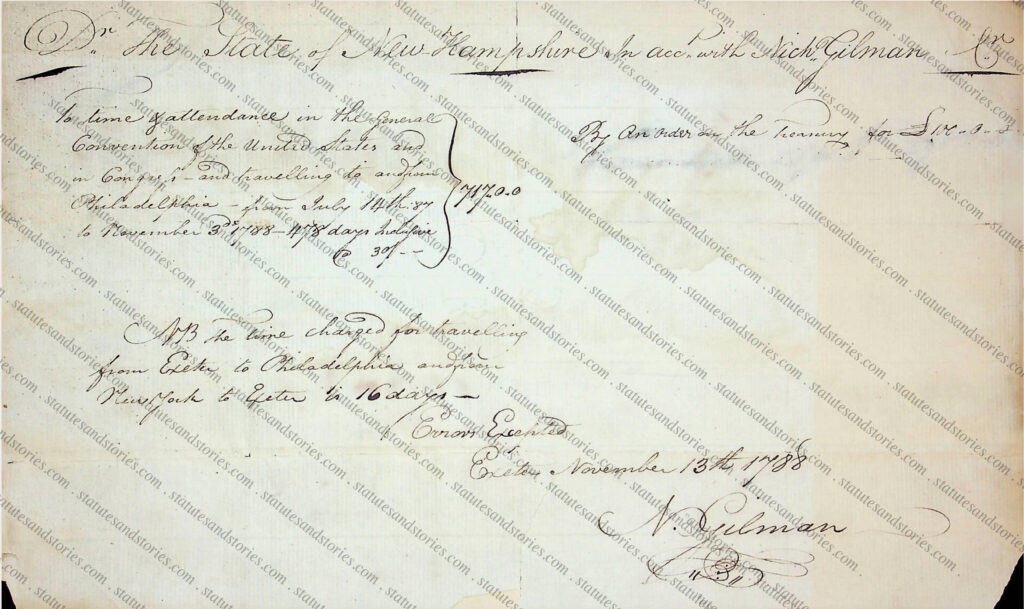

Newly identified proof of payment to Gilman

Once it became clear how the £139 and 10 shillings sum was calculated, this begged the question whether Gilman was also paid? Or, if Gilman was subsequently paid, did he reimburse Langdon?

Pictured above is the second recently discovered document that helps answer some of these pending questions. According to Gilman’s request, he sought reimbursement for the sum of £717 as follows:

To time of attendance in the General Convention of the United States and in Congress – and travelling to and from Philadelphia – from July 14th 87 to November 13rd – 478 days inclusive @ 30 [shillings per day]

Gilman’s math is correct, as 478 days at 30 shillings per day equals 14,340 shillings, which is equivalent to exactly £717. Gilman also records 16 days for the “time charged for traveling” from Exeter, New Hampshire, to Philadelphia in 1787, along with the return trip in 1788 from New York to Exeter.

Unfortunately, the notation on the right side of the page indicates that Gilman was only paid £100 pounds on or about November 13, 1788, after he returned from Congress after being away from home for over a year. It remains unclear whether subsequent installments were paid to Gilman of the remaining balance of £617 that he would have been owed. It is also unclear, as of yet, whether Gilman repaid Langdon for the sums that Langdon advanced to enable their trip to Philadelphia.

Whether and when Langdon and Gilman were fully compensated bears on the more consequential issue of the source for Congressional pay, as specified in the Constitution. According to Richard Beeman, the issue of payment of Congressional salaries was more than an abstract question. “When it came to matters of parsimony of state legislatures….Langdon rose to protest payment by the states, noting that states distant from the capital would bear a disproportionate share of the expense.”

Beeman further observes that Langdon’s concern was shared by the nationalists at the Convention who wanted to do everything in their power to render Congress independent of state governments and the “prejudices, passions, and improper views” of state legislatures. Ultimately, the Convention voted by a nine-to-two margin for Congressional salaries to be paid from the “National Treasury,” rather than by a delegate’s home state. This new protocal replaced the former practice under the Articles of Confederation of states paying (or not paying) salaries for members of Congress.

PostScript

A week after his arrival in Philadelphia, Gilman wrote home. In a letter to his cousin, Gilman indicated that his arrival with Langdon was “highly pleasing to the Convention,” during this “critical state of affairs.” Click here for a link to Gilman’s July 31 letter to Joseph Gilman. He observed that “much has been done (though nothing conclusively) and much remains to do.”

During the Convention Gilman did not actively participate in the debates. Accordingly, his letter to his cousin (which violated the Convention’s rule of secrecy) provides insights into his thinking. For Gilman, “A great diversity of sentiment must be expected on this great Occasion; feeble finds are for feeble measures…” Gilman predicted that the business of the Convention will not be completed until September.

On September 18, the day after the Convention concluded, Gilman wrote another letter to his cousin enclosing a copy of the Constitution:

…[I]t is the best that could meet the unanimous concurrence of the States in Convention; it was done by bargain and Compromise, yet notwithstanding its imperfections, on the adoption of it depends (in my feeble judgment) whether we will become a respectable nation, or a people torn to pieces by intestine commotions, and rendered contemptible for the ages.

Shortly thereafter, Langdon and Gilman traveled to Congress in New York with approximately ten of their fellow Philadelphia delegates, who were also members of Congress. Their attendance was critical to overcome anticipated resistance from Anti-Federalists who were plotting to contest the vote to send the Constitution to the states for ratification.

While Gilman was silent on the floor of the Constitutional Convention, he and Langdon were ardent supporters of the Constitution during the New Hampshire ratification debates. When the outcome of the New Hampshire ratification convention proved problematic in February of 1788, Gilman succeeded in obtaining adjournment rather than a no vote. This permitted delegates to return home to be released to vote freely in June, contrary to their original instructions to vote against ratification.

Langdon and Gilman would both be elected to the first Congress under the new Constitution in 1789. Each would also eventually become U.S. Senators. It is also noteworthy that Langdon was elected the first president pro tempore of the Senate on April 6, 1789. In that capacity he presided over the counting of the electoral votes which elected George Washington the first President of the United States.

Click here for a discussion of recently uncovered records in New York, proving that Alexander Hamilton, Robert Yates and John Lansing, Jr., were paid in 1788 for their attendance in Philadelphia.

Click here for a discussion of the discovery that Robert Yates attempted to return to the Convention in September of 1787 and the implications of this revelation.

Additional Reading and Sources:

Catherine Drinker Bowen, Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention (1966)

1787: The day-to-day story of the Constitutional Convention (1987)

Carol Berkin, A Brilliant Solution: Invention the American Constitution (2002)

Christopher and James Lincoln Collier, Decision in Philadelphia (2007)

David O. Stewart, The Summer of 1787: The Men who Invented the Constitution (2007)

Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (2009)