Delegate compensation and Virginia’s central role at the Constitutional Convention

Virginia played a central role in the creation of the Constitution. Virginia was the most populous state in 1787. It was also home to some of the most well respected voices of the day, including George Washington. James Madison, commonly referred to as the “father of the Constitution,” operated behind the scenes in calling for the Constitutional Convention. After the delegates assembled in Philadelphia, Madison’s “Virginia Plan” set the opening agenda for the Convention.

Easily overlooked by historians are the less obvious ways that Virginia embraced the Constitutional Convention, including the meaningful compensation timely paid to its seven delegates. As discussed below, Virginia’s financial support for its delegation facilitated their early arrival in Philadelphia, which contributed to the formulation of the consequential Virginia Plan.

This blog post is part of a multi-part series discussing delegate compensation and expenses during the summer of 1787. Part I begins with a review of existing scholarship by historians who have concentrated on this seminal period in American history. Part I compares delegate compensation across the twelve states that attended the Philadelphia Convention. As described in Part I, the Virginia legislature agreed to pay its delegates $6 per day, the highest amount approved by any state. Moreover, Virginia paid its delegates generous advances prior to their departure for Philadelphia.

Part II (pending) reviews efforts by historians to “judge” the performance of individual delegates at the Convention. Part II argues that delegate compensation is appropriately considered along with home state “support” when evaluating the contributions of individual delegates. In particular, the lack of financial and other support by the state of New York helps partially explain Hamilton’s poor comparative attendance at the Convention.

By contrast, Virginia and South Carolina provide examples of states which provided strong financial support for their delegates. It is thus not a surprise that Edmund Randolph of Virginia was one of only three sitting governors in attendance in Philadelphia. Likewise, the fact that South Carolina’s delegation was headed by former governor John Rutledge is consistent with this explanation. The thesis that delegation compensation mattered is also supported by the fact that South Carolina was one of only four state delegations with a quorum on May 17. As described in George Washington’s diary, only 4 states, Virginia, South Carolina, New York and Pennsylvania “are as yet represented, which is highly vexatious to those who are idly and expensively spending their time here.”

Part III (pending) provides state-by-state examples of the primary sources, including correspondence, receipts, financial ledgers, audits, statutes, legislative journals and resolutions that were used for this wide ranging analysis of delegate compensation. Separate blog posts summarize recent discoveries in the New York and New Hampshire state archives, which shed new light on the difficulty many delegates experienced in getting reimbursed.

As discussed below, Virginia was arguably the most supportive, pro-reform state going into the Constitutional Convention. Virginia appointed seven delegates to Philadelphia, the second largest state delegation. Only Pennsylvania, which was host to the Convention, appointed more delegates. It is universally recognized that Benjamin Franklin (one of Pennsylvania’s eight delegates) and George Washington (one of Virginia’s seven delegates) were the two most famous and beloved Americans at the time.

Virginia’s other well-respected delegates included its Governor, Edmund Randolph, Judge George Wythe (the nation’s first law professor), George Mason (the author of the Virginia Constitution and its influential Bill of Rights), and of course James Madison and Washington. Thus, the reputation and credentials of the Virginia delegation signaled to the nation that the Convention should be taken seriously. In turn, Virginia compensated its delegates commensurate with their station.

Virginia’s indispensable role in creating the Constitution

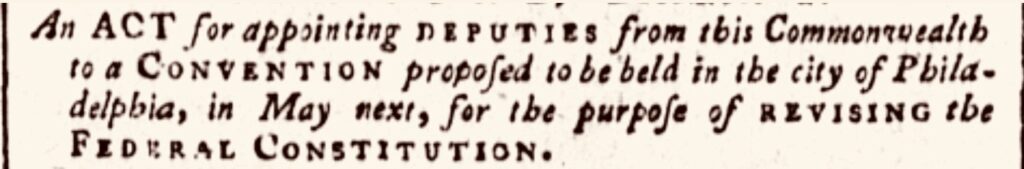

Well before the delegates began assembling in Philadelphia in May of 1787 Virginia played a leading role calling for and facilitating the Constitutional Convention. In November of 1786 Virginia’s “Act for appointing Deputies” to Philadelphia provided a template for other states to follow. The influential Act written by James Madison was widely reprinted in the newspapers and disseminated around the country. Click here to a link to the Act, the title of which is copied below.

Indeed, it could be argued that the road to Philadelphia started in Virginia. The Virginia Legislature initiated the process of calling a national convention. In January of 1786 Virginia invited all states to meet in Annapolis in September of 1786 to discuss interstate commerce. The Annapolis Convention grew out of the earlier Mount Vernon Compact of 1785 between Virginia and Maryland, the first interstate compact of its kind addressing navigation of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. According to Professor John Kaminski and his colleagues, these early efforts arose in the “vacuum created by Congress’ lack of power to regular commerce.”

After the Annapolis Convention failed to secure a quorum, Virginia was the first state to endorse the Annapolis Convention’s September 14 call for a Constitutional Convention to meet in Philadelphia in May of 1787. Following the aborted Annapolis Convention, Virginia adopted its influential Act for appointing deputies “to a Convention proposed to be held in the City of Philadelphia in May next, for the purpose of revising the Federal Constitution.”

Borrowing from the Annapolis Convention report written by Alexander Hamilton, the Virginia Legislature endorsed the proposed Philadelphia Convention and called for the appointment of delegates to Philadelphia to devise and discuss “all such alterations and further provisions, as may be necessary to render the Federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of the Union….” According to Virginia’s November 23 Act written by Madison:

[The General Assembly] can no longer doubt that the crisis is arrived at which the good people of America are to decide the solemn question, whether they will by wise and magnanimous efforts reap the just fruits of that independence, which they have so gloriously acquired, and of that union which they have so gloriously acquired, and of that union which they have cemented with so much of their common blood….

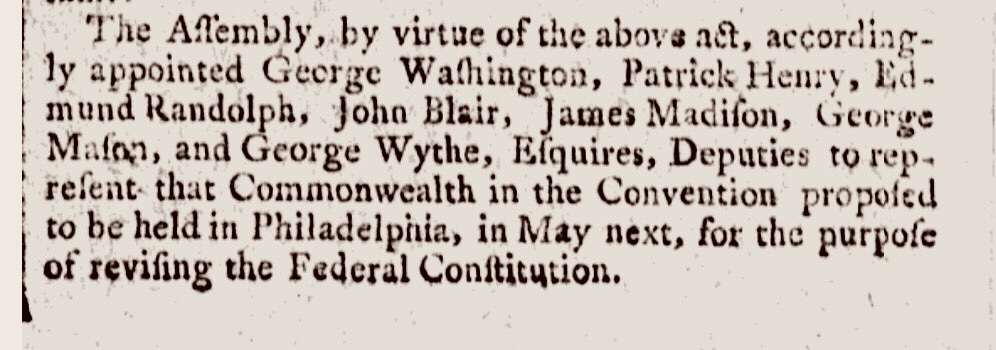

Shortly thereafter, Virginia appointed its influential slate of delegates on December 4, 1786. After its adoption Governor Randolph promptly wrote to the chief executives of all the states forwarding a copy of Virginia’s November 23 Act. He followed up by forwarding the list of Virginia appointees, to be headed by George Washington.

Pictured below is an example of a newspaper report of the December 4 Act appointing the influential Virginia delegation. Patrick Henry would famously decline the appointment and would subsequently be replaced by Dr. James McClurg, who was a member of the Virginia Privy Council.

When the Pennsylvania General Assembly appointed its delegates on December 30 it cited to the Virginia Act. The Pennsylvania Act, in turn, indicated that, “the Legislature of this state are fully sensible of the important advantages which may be derived. . . from co-operating with the commonwealth of Virginia, and the other states of the confederation….” When appointing its delegates on February 3, Delaware similarly cited the Virginia Act, expressing Delaware’s desire to cooperate with Virginia “in so useful a design.”

Virginia delegate compensation

Virginia clearly helped blaze a path by calling on the states to send delegates to Philadelphia. As described below, Virginia also took the call to action seriously in other ways that are easily overlooked. In December of 1786, well in advance of the Philadelphia Convention, the Virginia legislature approved meaningful compensation of $6 per day for its delegates. Virginia then paid £ 100 advances to each of its delegates prior to their departure for Philadelphia. Importantly, doing so facilitated the timely arrival of the Virginia delegates in Philadelphia, as requested by Madison and likely expected by George Washington.

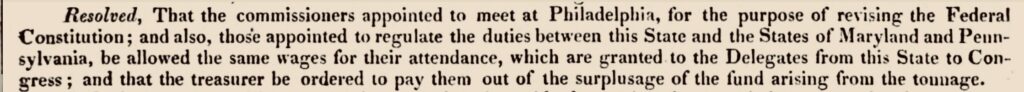

Pictured below is the Virginia Resolution providing for the payment of the “same wages” for its Convention delegates that Virginia paid to members of Congress.

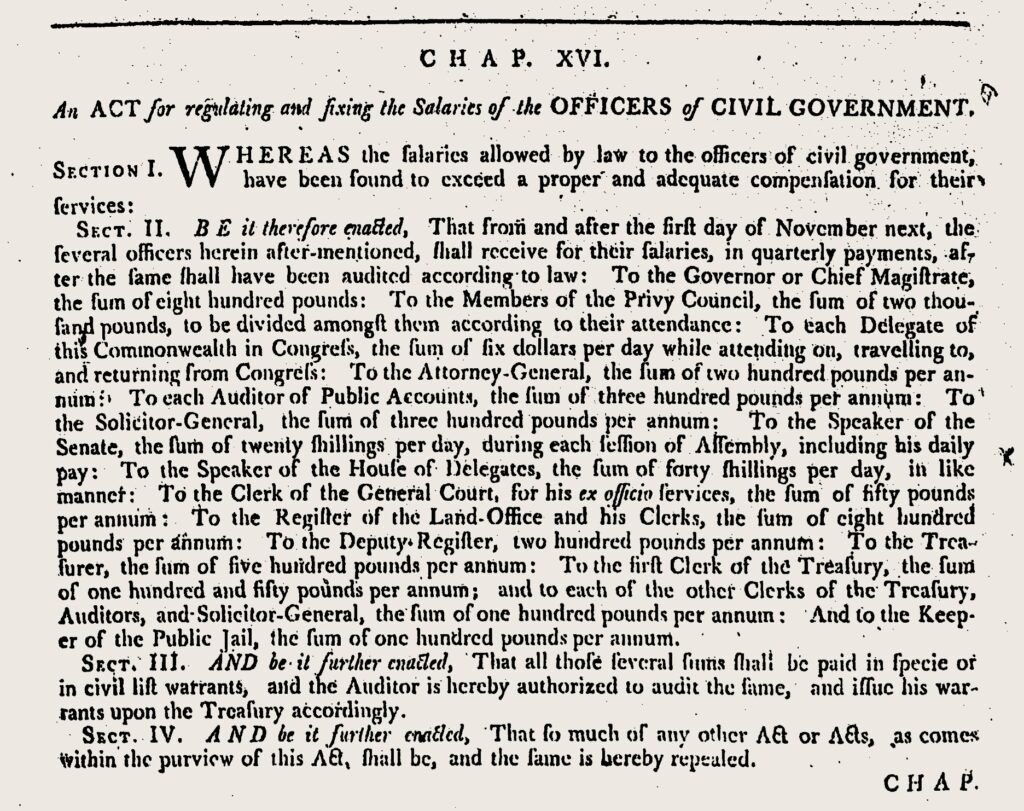

Dating back to 1785, Virginia paid $6 per day to its Congressional delegates. The subsequent December 1786 Resolution authorizing wages for Virginia’s Philadelphia Convention delegates built on the 1785 “Act for regulating and fixing” salaries pictured below:

It is also useful to appreciate that Virginia offered the use of its navy to assist with the transportation of its delegates to Philadelphia. At the time, Virginia maintained two “state boats” (the Liberty and the Patriot) which were retained as revenue cutters following the Revolutionary War. The proposal to offer the “State boat Liberty” to carry delegates “to the head of the bay” was approved by the Governor’s Privy Council on March 8, a full two months before delegates needed to depart for Philadelphia.

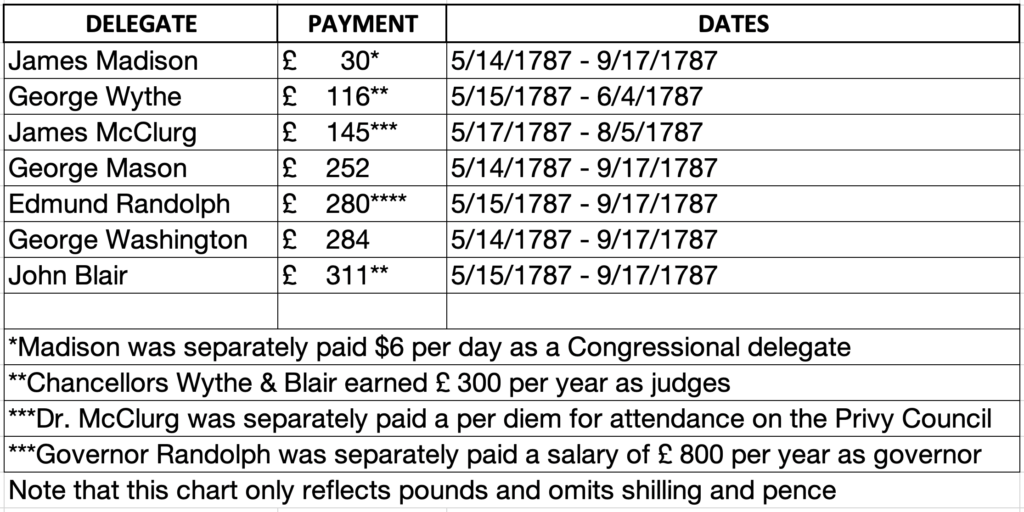

Payments to the Virginia delegates were meticulously recorded in the state’s official journals and ledgers. StatutesandStories.com owes a debt of gratitude to the Virginia State Archives and Reference Archivist Kevin D. Shupe who painstakingly obtained the journals, ledgers and other receipts requested for this project. The detailed journals provide a daily account of payments and income. The same amounts recorded in the daily journals were contemporaneously entered in separate ledgers for each payee. By cross referencing the journals and ledgers it is possible to verify that the following sums were paid to the Virginia delegates for their work at the Constitutional Convention:

As evidenced by the Virginia journals and ledgers, it is noteworthy that funds were advanced to pay the Virginia delegates beginning on April 17. Earlier in the month, on April 2, Governor Randolph wrote to George Washington inquiring “how I shall forward the money to be advanced from the treasury.” At the time, Washington had not committed to attending the Convention and replied on April 9 that, “If I should attend the Service, it will suit me as well to receive it from you in Philadelphia as at this place. If I should not, I have no business with it at all.”

On April 15 Madison wrote to Governor Randolph encouraging punctual arrival. Madison apologized that Randolph would be traveling without his pregnant wife, but justified the sacrifice as necessary:

Virginia ought not only to be on the ground in due time, but to be prepared with some materials for the work of the Convention. In this view I could wish that you might be able to reach Philada. some days before the 2d. Monday in May.

Madison advised Washington in a letter dated April 16 that he had “formed in my mind some outlines of a new system, I take the liberty of submitting them without apology, to your eye.” Madison’s outline along with his Vices of the Political System of the United States (Madison’s so-called “Vices”) would lay the groundwork for the Virginia Plan.

According to historian Richard Beeman:

James Madison, more than any other delegate, would provide the combination of intellectual firepower and dogged persistence that animated the Convention. Washington would contribute not merely his prestige and gravitas, but, just as importantly, his calm and deliberative leadership.

According to Madison’s Notes of Debates in Congress, Madison left New York to travel to Philadelphia on May 2. Ever punctual, Washington arrived on May 14, the scheduled first day of the convention. Yet, Washington and Madison, along with a few members of the Pennsylvania delegation, were the only delegates to arrive on time to start of the Convention.

Randolph, who was a new father, arrived on May 15, following the birth of his daughter. By May 17, the entire Virginia delegation was in attendance. The only other state with a full delegation on May 17 was Pennsylvania, the Convention’s host. Other state delegations were much slower to arrive. As described in Washington’s diary on May 14:

[t]his being the day appointed for the Convention to meet…but only two states being represented – viz – Virginia and Pennsylvania – agreed to attend at the same place at 11 o’clock tomorrow.

Historian Richard Beeman refers to this slow start to the Convention as “the delay that produced a Revolution.” As described by Virginia delegate George Mason in a letter dated May 20 to his son, “[t]he Virginia deputies (who are all here) meet and confer together two or three hours every day, in order to form a proper correspondence of sentiments….” In other words, the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations used the time between May 14 and May 25 – when a quorum was finally achieved – to prepare the Virginia Plan. By doing so, Madison and Randolph were able to effectively set the agenda for the Convention, along with the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegates. The rest is history.

Signers and dissenters from Virginia

Admittedly, only three of Virginia’s seven delegates actually signed the Constitution: Washington, Madison, and Judge Blair. One could cynically ask whether the generous compensation paid by Virginia to its delegates made any difference? It is suggested that Virginia obtained tremendous value for its investments in delegate compensation, notwithstanding the fact that other states had more signatories subscribe their names on the Constitution on September 17.

Famously, on the last day of the Constitutional Convention, a total of three of the thirty-eight delegates in attendance refused to sign the Constitution. Importantly, two of the three dissenters were Virginia delegates Edmund Randolph and George Mason.

Accordingly, Virginia was the only state with two delegates who refused to sign on September 17. George Mason objected over the lack of a bill of rights. He suggested that one could be quickly prepared using the Virginia Bill of Rights, which had been drafted by Mason a decade earlier. Governor Randolph was critical of insufficient checks and balances in the Constitution, which he thought could be remedied by a second Convention. Randolph also wanted to keep his options open to preserve his independence as a sitting governor during the ratification process. Importantly, Randolph would later support ratification and be appointed by Washington as the nation’s first attorney general.

Virginia delegate George Wythe was forced to return home on or about June 4th due to his wife’s poor health. Virginia delegate James McClurg departed the Convention on or about August 5th fearing that his vote would further divisions within his delegation.

Yet it is noteworthy that dissenting delegates from other states generally returned home, rather than remaining in Philadelphia. For example, New York delegates Robert Yates and John Lansing departed Philadelphia on or about July 10 voicing their opposition to the Virginia plan. Similarly, Maryland delegates Luther Martin and John Francis Mercer walked out on September 3. Consequently, one can argue that the compensation paid to Virginia’s delegates and the sense of ownership that they felt may have motivated Randolph and Mason to remain in Philadelphia until the Convention finally adjourned.

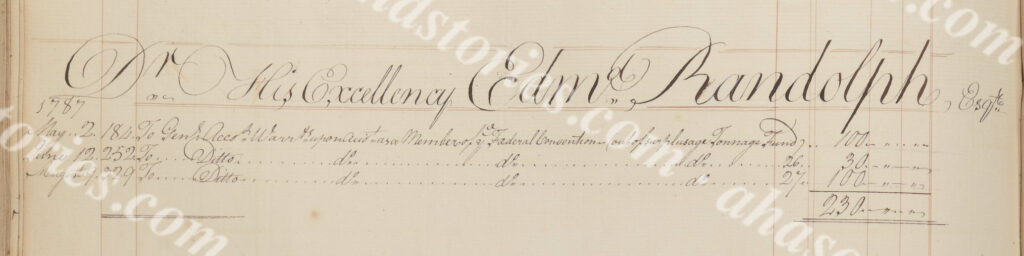

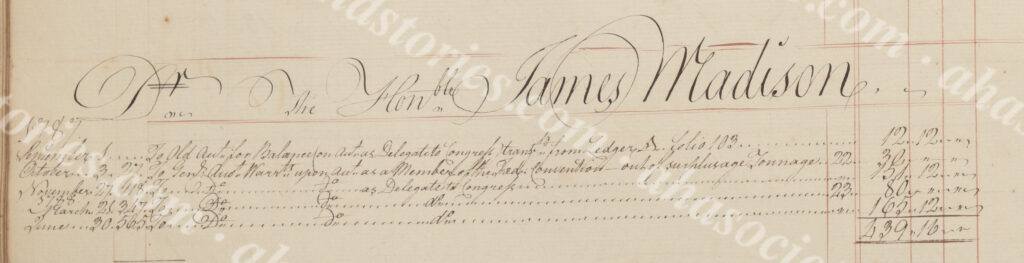

Virginia accounting records documenting delegate compensation

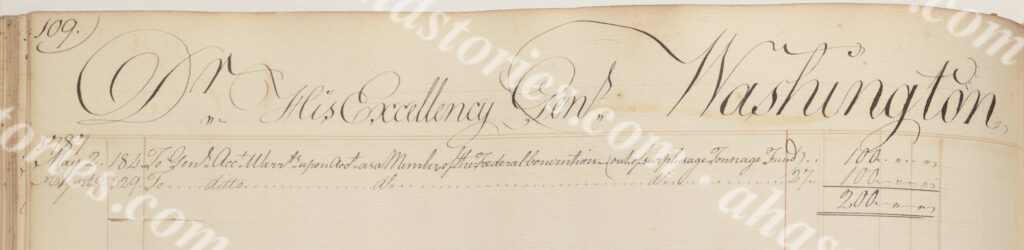

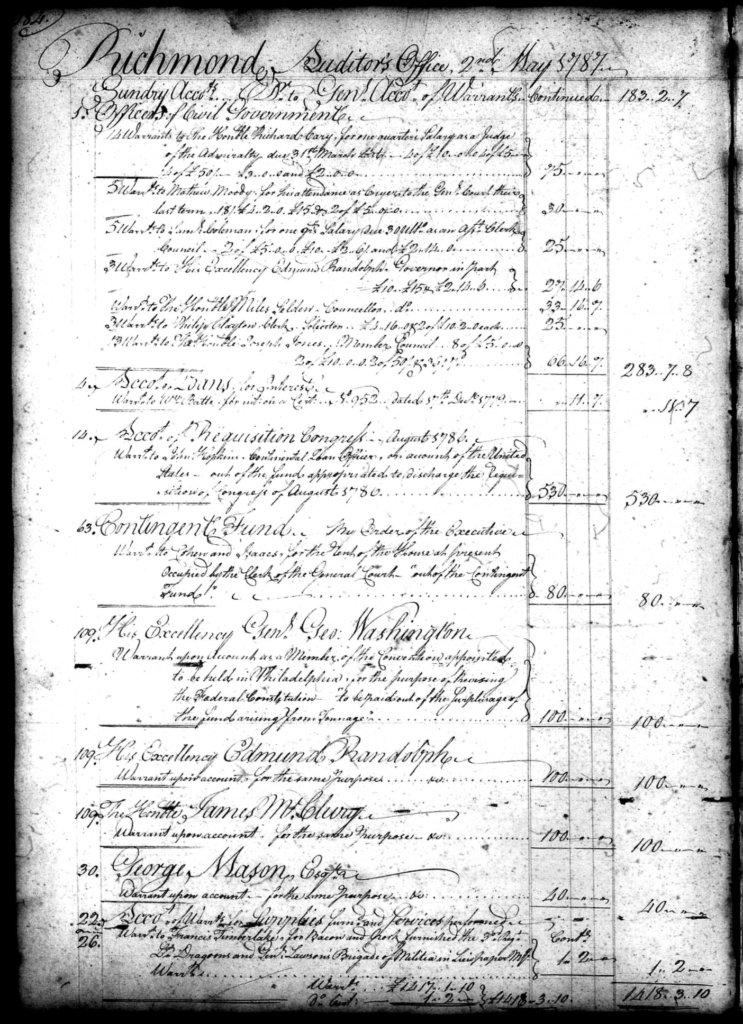

Pictured below are examples of ledgers and journal entries evidencing the exact amounts paid to Virginia’s delegates for their work during the summer of 1787. A supplemental blog post of Virginia Journals and Ledgers will provide images of dozens of relevant Virginia journal and ledger entries, which may be useful for scholars and researchers. Given the detailed records which were created by Virginia’s auditors/bookkeepers, it is possible to track the amounts and timing of distributions that Virginia paid to its delegates.

Interestingly, it is also possible to compare the dates of payments, along with the dates of requests for payments, as reflected in correspondence between the delegates and Governor Randolph’s administration in Richmond. This exercise demonstrates that there were certainly advantages to having Virginia’s Governor lead the state’s delegation in Philadelphia. By contrast, delegates from other states were commonly frustrated by the delays in obtaining reimbursement, in several cases forcing delegates to borrow money or move to less expensive accommodations.

For example, Governor Edmund Randolph wrote to Lieutenant Governor Beverley Randolph on June 6 indicating that, “[t]he prospect of a very long sojournment here has determined me to bring up my family.” Governor Randolph requested thirty pounds for travel expenses to be delivered to Mrs. Randolph. Illustrating how there were advantages to being Governor, his Excellency’s ledger reflects the prompt payment of 30 pounds on June 12, as requested.

This article continues with a supplemental blog post of Virginia Journals and Ledgers, providing dozens of images of financial records evidencing payments to Virginia’s delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787.