Virginia Delegate Compensation – Journals & Ledgers

The state of Virginia played a central role in the creation of the United States Constitution. In fact, it can be argued that Virginia was the most supportive, pro-reform state when the Constitutional Convention began its deliberations in May of 1787. This supplemental post continues the discussion of the compensation paid to Virginia’s delegates to the Constitutional Convention. In addition to sharing dozens of images, this supplemental post discusses insights – and as yet unanswered questions – that arise from the primary sources collected below.

At the outset, it is important to recognize that this work would not have been possible without the invaluable assistance of Kevin D. Shupe, Reference Archivist at the Library of Virginia, and Ben Steck, Digital Collections Specialist. Thanks to their efforts StatutesandStories.com is pleased to provide online access to the these records.

It is hoped that these materials will be of assistance to future researchers and scholars who may be able to dive deeper into these archival records to answer remaining questions posed below. In addition to the images provided by Kevin and Ben, other images were copied from microfilm obtained by interlibrary loan from the Library of Virginia (“Auditor of Public Accounts, Receipts and Disbursement Journals,” Reels 6257-6259). The availability of interlibrary loans (in this case delicate microfilm) during a pandemic is much appreciated, which justifies a special thanks to Amy Miller, the Interlibrary Loan Manager for Broward County’s Main Library.

Background about Virginia’s key role

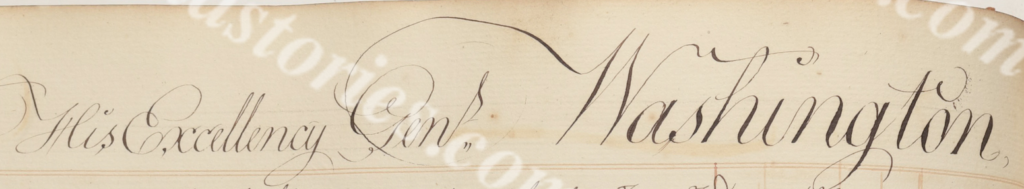

As described in the preceding post about Virginia Delegate Compensation (Part I), Virginia helped blaze a path by calling on the states to send delegates to Philadelphia. Virginia’s “Act for appointing Deputies” to Philadelphia provided a template for other states to follow. Moreover, the reputation of the Virginia delegation, including George Washington, signaled to the nation that the Convention should be taken seriously. In turn, Virginia compensated its delegates commensurate with their station.

Virginia’s generous financial support for its delegation facilitated their early arrival in Philadelphia, which contributed to the formulation of the Virginia Plan. In December of 1786, well in advance of the Philadelphia Convention, the Virginia legislature approved meaningful compensation of $6 per day for its delegates. Virginia then paid £ 100 advances to each of its delegates prior to their departure for Philadelphia.

Part I further suggests that the compensation package offered by Virginia encouraged its delegates to remain in Philadelphia. For example, Governor Randolph and George Mason are rare examples of holdout delegates, who remained in Philadelphia despite their misgivings. Randolph and Mason contrast with Robert Yates and John Lansing (of New York), Luther Martin and John Francis Mercer (of Maryland), and other “proto-Anti-Federalists” who simply left town when they disagreed with the direction that the Convention was taking. Delegate compensation paid by the other twelve states is discussed here.

There were obvious advantages to having a sitting governor lead a state delegation. For example, Governor Randolph was able to secure additional advances of £100 per delegate in August, as the Convention continued its deliberations in the late summer. Other state delegations struggled financially as the Convention continued into September.

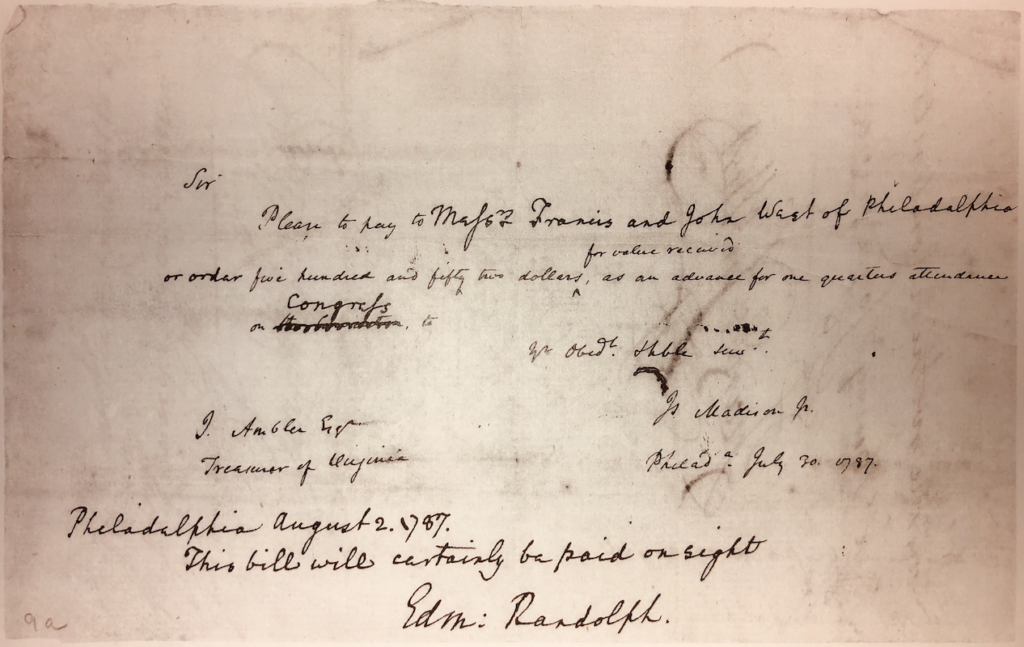

Pictured below is a request by James Madison for an advance of $550 for one quarter of his annual Congressional salary. Because Governor Randolph was attending the Convention, he was able to personally sign the expedited request in Philadelphia on 2 August 1787, writing that “[t]his bill will certainly be paid on sight.” The $550 corresponds to approximately 90 days of pay to Madison, at the rate of $6 per day.

A future blog post will explore the implications of a curious “revision” to this document. It appears that it was important for Madison and/or Randolph to distinguish between Madison’s work as a delegate to Congress versus his work as a member of the Federal Convention.

The journals and ledgers pictured below are particularly useful when viewed in their totality and contrasted with similar financial records from other states. The difficulty of gaining access to this material in twelve separate state archives may help explain why the observations/questions below may have been overlooked by prior generations of historians. StatutesandStories invites other researchers and scholars to follow this research trail.

Images and Research Questions:

The materials pictured below support the following observations and prompt the following unresolved questions:

- Several of the Virginia delegates were state “employees.” These delegates continued earning their salary at the same time that they were separately being paid a per diem to attend the Convention. This fact only become evident when reviewing the state ledgers and journals.

- Governor Randolph, Chancery Court judges Wythe and Blair, and Privy Council member McClurg all received compensation from the state of Virginia in 1787. Madison was the only Virginia delegate who was also a member of Congress. George Washington and George Mason were not salaried state employees, making it more expensive for them to leave their plantations, Mt. Vernon and Gunston Hall.

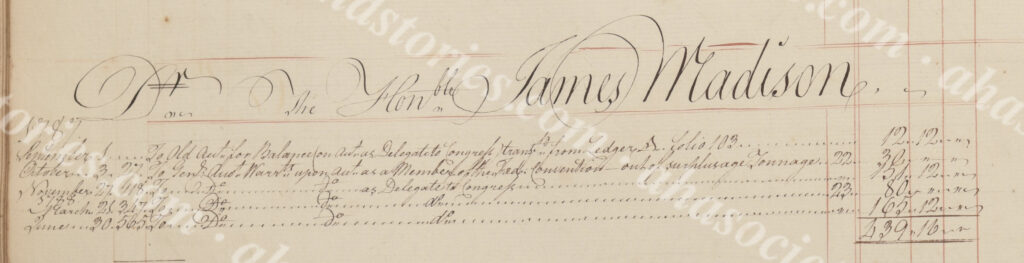

- As a member of Congress from Virginia James Madison was paid $6 per day. This explains why, surprisingly, Madison did not receive the same £100 advance paid to the six other Virginia delegates.

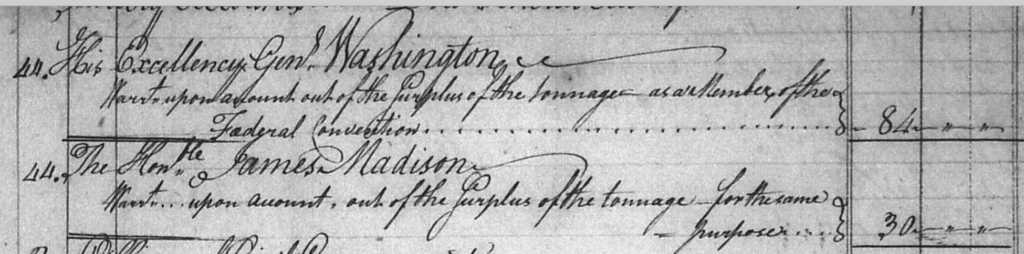

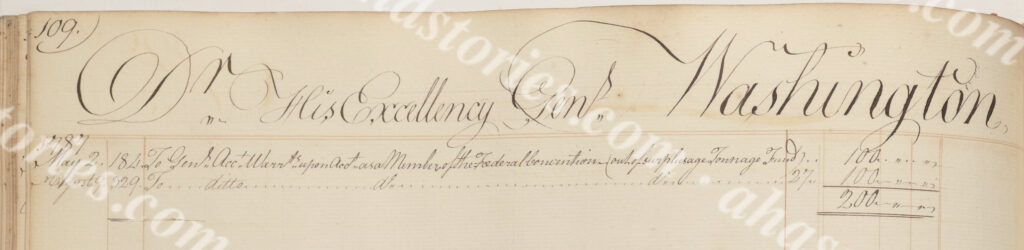

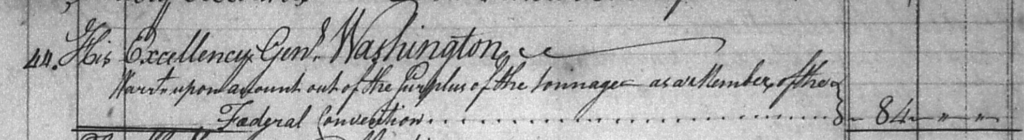

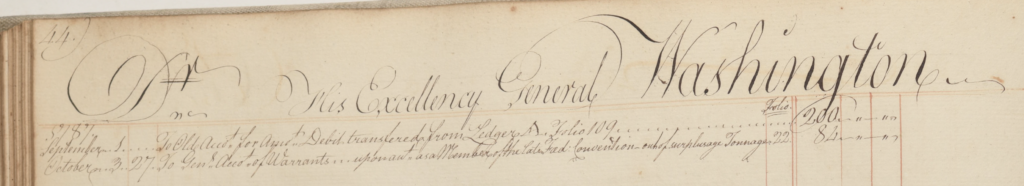

- There is one exception to this general rule that Madison was not separately paid for his work as a Convention delegate. On October 3, Madison was paid £ 30 as a “Member of the Federal Convention.” It is unclear what this amount pictured above represents, since the ledgers and journals do not provide any further details how this amount was calculated. George Washington similarly received an additional payment of £ 84 on October 3, after the Convention adjourned on September 17.

- Madison’s Congressional pay of $6 per day raises an interesting question. As the other state employees (Randolph, Wythe, Blair and McClurg) were separately paid $6 per day as delegates along with their regular salary, could Madison have similarly requested both his Congressonal pay of $6 per day, plus the delegate expense reimbursement of $6 per day?

- Regarding Madison’s request for an advance of his salary pictured above, why did Governor Randolph strike through the phrase “the Convention” to clarify that Madison was being paid as a member of “Congress”? Does the answer to this question explain why Madison wasn’t separately reimbursed both his Congressional salary and the per diem authorized for Convention delegates? The original description appears to be written in Madison’s handwriting. The text at the lower half of the page, above Randolph’s name, appears to be in Randolph’s handwriting. This issue will be discussed in a subsequent post asking Whether Madison was underpaid for his work in Philadelphia (pending).

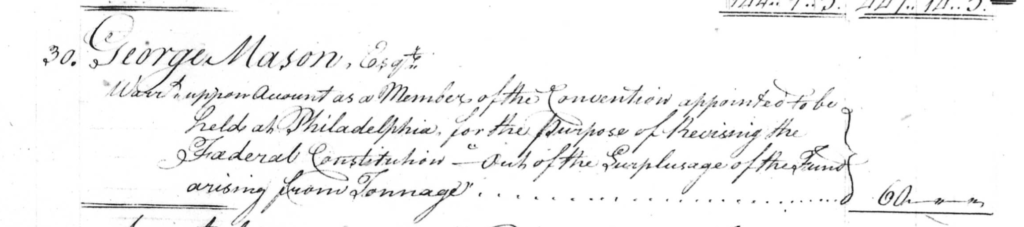

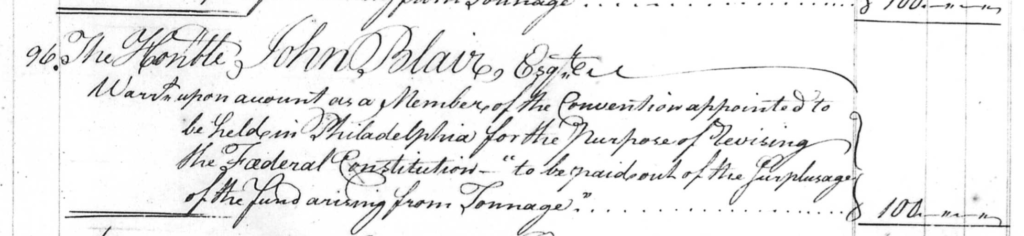

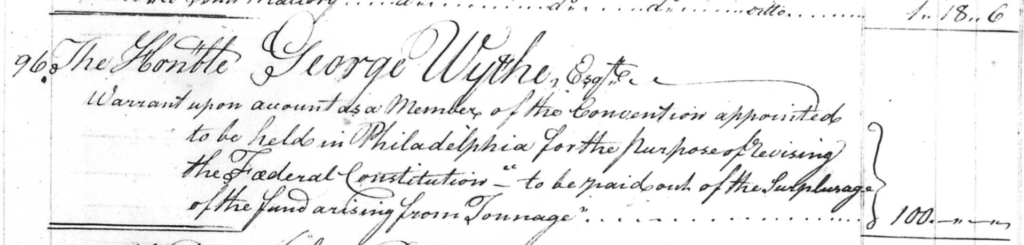

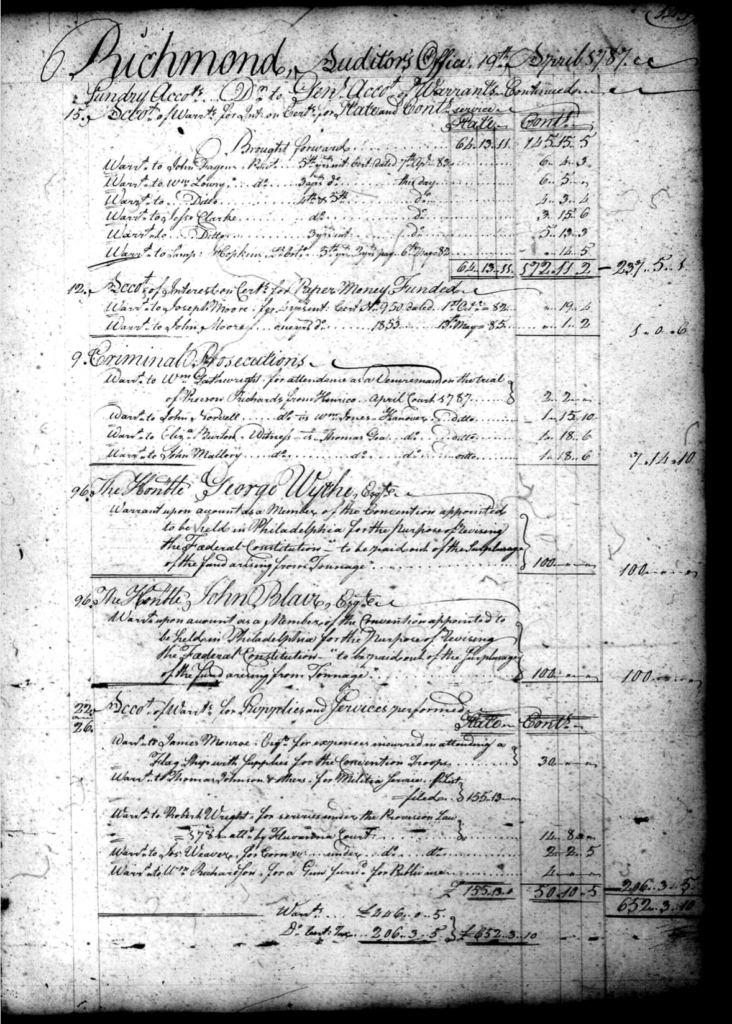

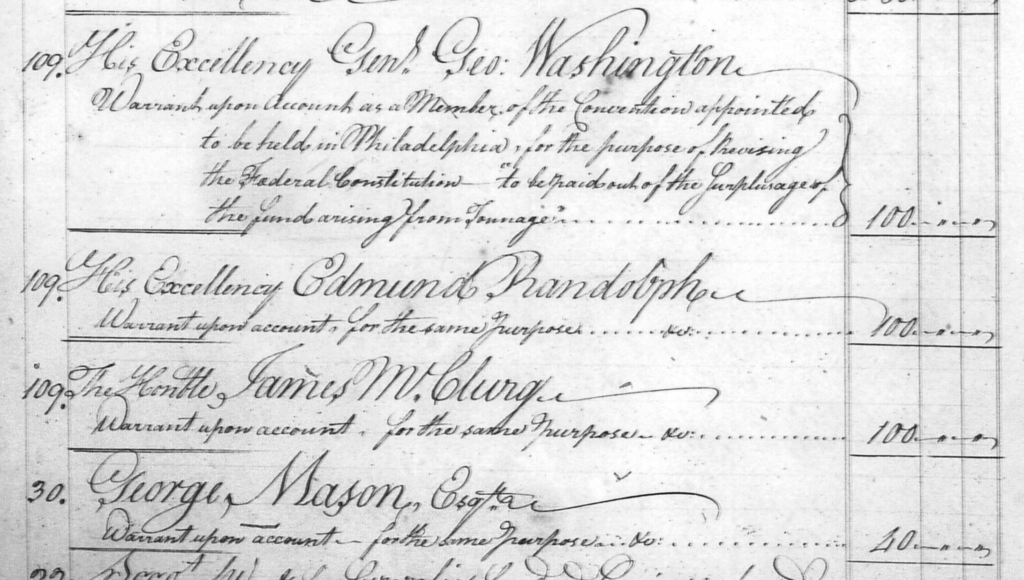

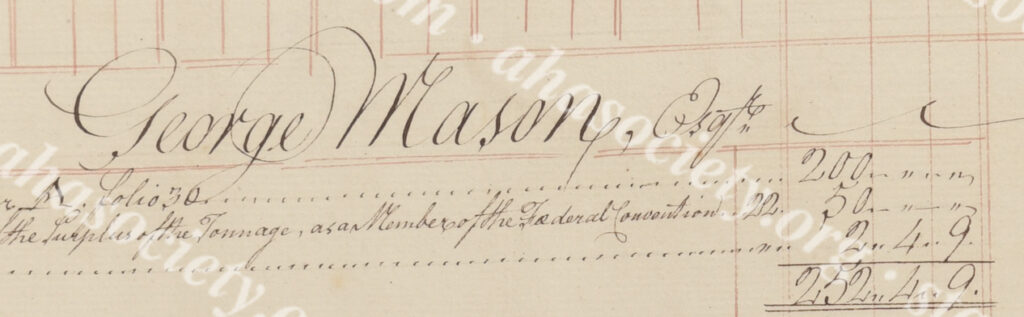

Pictured below is the £100 per delegate advance that was paid to all of Virginia’s delegates in April/May, but not paid to Madison. Mason was the first to receive an initial advance of £60 on April 7. Wythe and Blair received a full advance of £100 on April 17. Mason was paid the balance of £40 on May 2.

April 7 (Mason) and April 19 (Blair and Wythe) Journal entries

April 19 Journal (sample of an entire page)

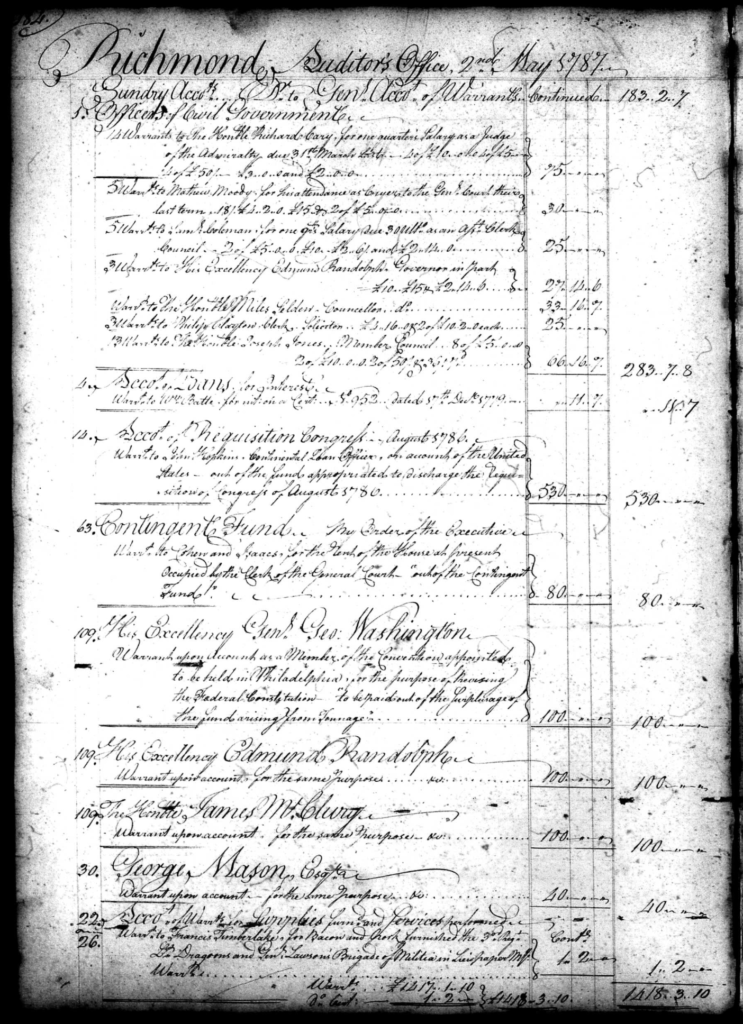

The remaining Virginia delegates were paid £100 in May, except for Madison. Mason received a second installment of £ 40 on or about May 2, resulting in a full advance to Mason of £ 100.

May 2 Journal (sample entire page)

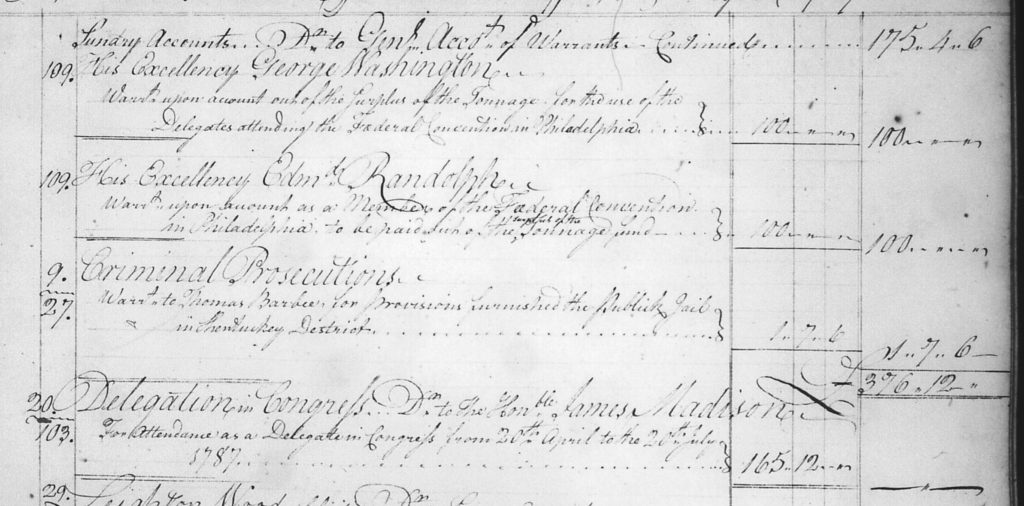

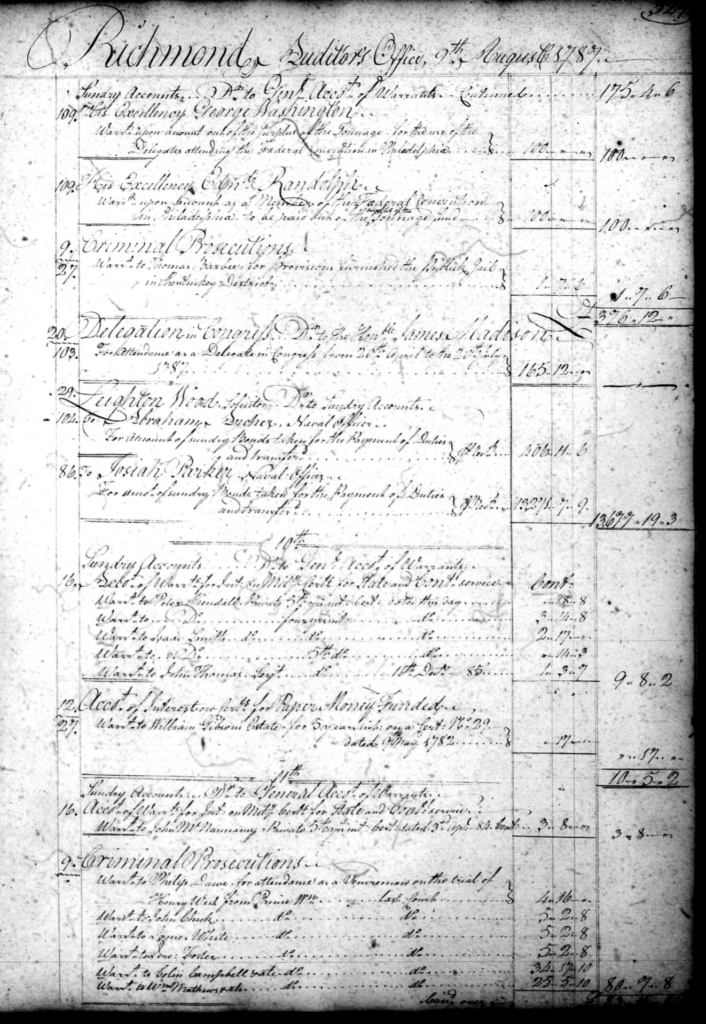

Pictured below is a second round of £100 advances that were paid in August of 1787. At the time, it was clear that the Convention’s work would continue into September. Unlike the other Virginia delegates, Madison didn’t receive an initial £100 advance. Instead, he was paid £165 and 12 shillings “[f]or attendance as a Delegate in Congress from 20th of April to the 20th of July.”

August 9 Journal entries

August 9 Journal (sample entire page)

- George Washington was paid a total of £ 284 for his attendance at the Convention.

- In addition to two £ 100 pound advances, Washington was also paid a final distribution of £ 84 on October 3.

- During his time in Philadelphia Washington stayed at Pennsylvania delegate Robert Morris’s mansion. Washington originally planned to board at Mrs. Mary House’s boarding house (SW corner of 5th and Market) with most of the other Virginia delegates. Yet on the day of Washington’s arrival into Philadelphia Morris prevailed upon Washington to stay with the Morris family, rather than boarding in a public boarding house.

- It appears that the money he saved by residing with Robert Morris enabled Washington to repay a longstanding debt that he owed to New York Governor George Clinton for a joint investment in New York real estate. While George Washington was wealthy, southern planters were often illiquid and frequently lacked ready access to specie (hard currency).

- Washington and Clinton purchased the 6,071 acres in the Townships of Coxeborough & Carolana in Montgomery County, New York, in November of 1784. On June 9, Washington wrote to Governor Clinton from Philadelphia indicating that he would be able to repay the balance of the $840 loan, which he described was equivalent to £325.6.0. Washington recorded the repayment in his cash book which tracked his expenses while in Philadelphia.

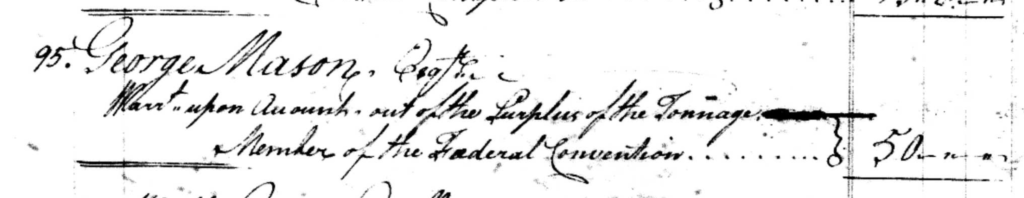

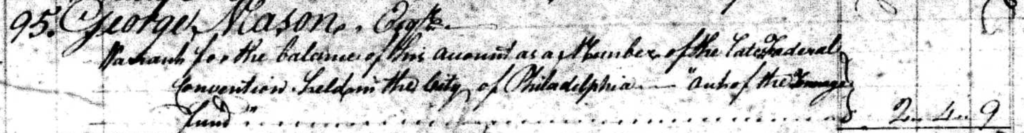

- George Mason was paid a total of £ 252, 4 shilling and 9 pence for his work as a delegate in Philadelphia.

- Mason boarded at the Indian Queen boarding house (4th Street between Market and Chesnut).

- In a letter to his son dated May 20, Mason described that while he found traveling “very expensive,” living in Philadelphia was “cheap.” At the Indian Queen on Fourth Street, “we are very well accommodated, have a good room for ourselves, and are charged only twenty-five Pennsylvania currency per day, including out servants [slaves] and horses, exclusive of club in liquors and extra charges.” Mason explained that he hoped that he would “be able to defray my expenses with my public allowance, and more than that I do not wish.”

Currency rates and comparisons

- By comparison, Manasseh Cutler’s Journal, a famous primary source from 1787, describes Cutler’s trip to Philadelphia during the Convention. Cutler’s journal on July 13-14 describes that the bill for staying two days at the Indian Queen was “36 s. 9 d.” It is unclear if this amount was 36 shilling and 9 pence, or if the “d” was for dollars (which makes sense since 36 shilling was roughly equivalent to 9 or 10 dollars) ? It is also unclear if this charge was for room and board, or only the room? The journal does not indicate whether these sums were paid in local Pennsylvania currency.

- Cutler’s two day bill at the Indian Queen averages out to approximately 18 shilling per day.

- The conversion rate from shilling to pounds is: £1 = 20 shilling. Thus, Cutler’s bill was approximately £1 per day. Presumably a weekly or monthly stay might have been at a lower, discounted rate? Cutler only boarded for two days, whereas the Convention delegates might have been able to negotiate, lower, longer term rates.

- William Samuel Johnson, a delegate from Connecticut, also recorded his expenditures. On June 9 Johnson paid £ 3, 7 shilling and 6 pence for a week of boarding at the City Tavern. This weekly sum would average approximately half a pound per day, which is equivalent to 10 shillings per day.

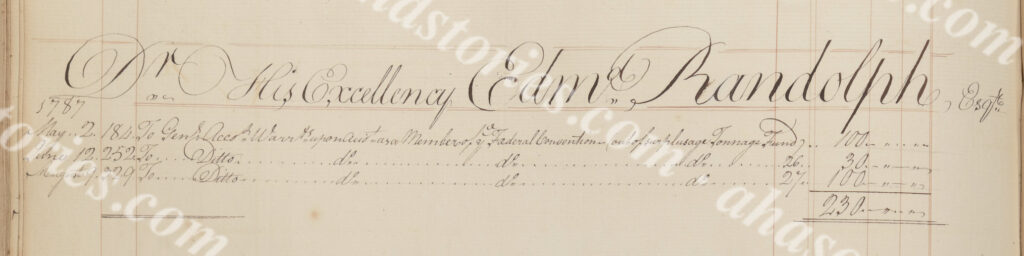

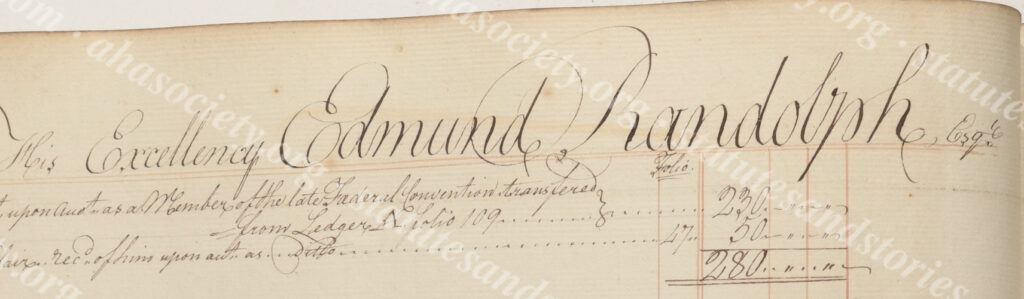

Governor Randolph:

- Governor Randolph earned a £800 annual salary as Governor, along with the £280 pounds that he was paid to attend the Convention. Virginia generally paid its public officers in quarterly installments.

- Virginia’s delegates received £ 100 advances prior to the Convention. The magnitude of these advances becomes clear when comparing the £ 100 advance with Governor Randolph’s £200 quarterly salary.

- Randolph’s daughter, Edmonia, was born in April. The young Governor, not wanting to be separated from his wife and infant daughter, arranged for his family to join him in Philadelphia. To prepare for their arrival, Randolph rented “a couple of rooms in a house a small distance” from Mrs. House’s boarding house. In a letter dated May 25, George Read of Delaware described that he had arranged for John Dickinson to move into Randolph’s room, which was located “on the first floor, up one pair of stairs, on 5th Street.”

- According to a June 6 letter from Governor Randolph to Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor:

The prospect of a very long sojournment here has determined me to bring up my family. They will want about thirty pounds for the expense of travelling. The Executive will therefore oblige me by directing a warrant in my favor, to be delivered to Mrs. R. for that amount.

- Governor Randolph elaborated that as of June 6 he had expended £57 pounds, 12 shilling from the £100 pounds that he had been advanced on May 2, leaving him with a balance of £42.8 “now in my hands.”

- Randolph summarized that “[m]y account stands thus”:

[b]y attending from the 6th of May to this day (both inclusive), 32 days, at 6 dol. per day, which amount to 192 d’s, and are equal to…….£5.12s.

Twenty-three or four days more will overrun this sum, and will have elapsed before my family can arrive, so that I trust there will be no difficulty with the advance.

Ledgers showing Randolph’s Convention pay of £280

The first ledger pictured below reflects payments of £230 to Governor Randolph for service as a “Member of the Federal Convention.” The second, updated ledger, reflects a final payment of £50 on October 9, increasing his total Convention pay to £280.

Journal entries showing quarterly installments of Randolph’s salary

Copied below are journal entries reflecting quarterly installments of Governor Randolph’s £800 per year salary. Interestingly, he was paid over £400 pounds in November and December, suggesting that he did not find it necessary to draw his salary earlier in the year. Presumably, Governor Randolph didn’t need the funds since he was also receiving the $6 per day delegate pay, which totaled £280 when converted to pounds. Thus, for the year, Randolph was paid approximately £1,080 (£800 salary and £280 delegate pay).

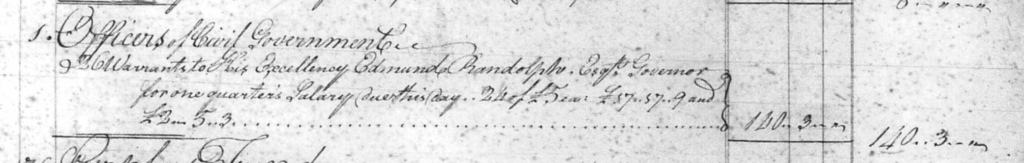

April 30 journal entry (£140 installment of Randolph’s salary)

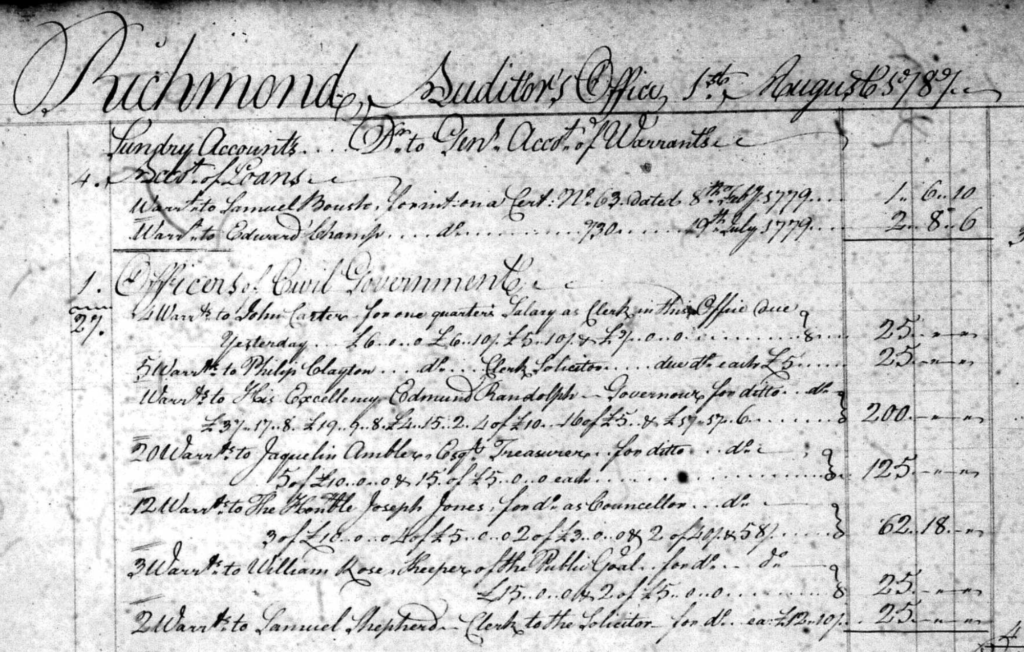

August 1 journal entry (£200 installment of Randolph’s salary)

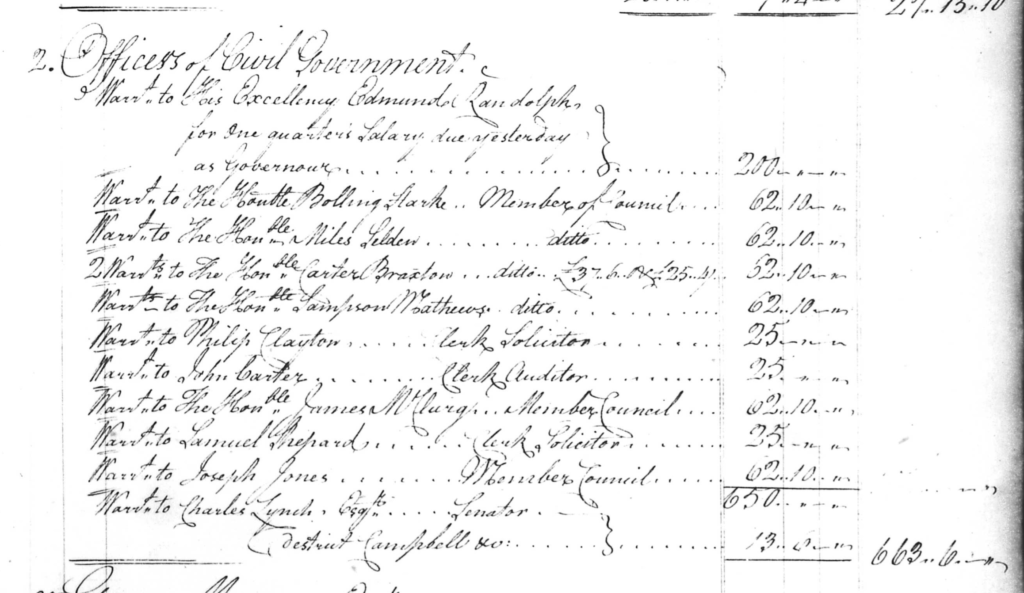

November 1 journal entry (£200 salary installment)

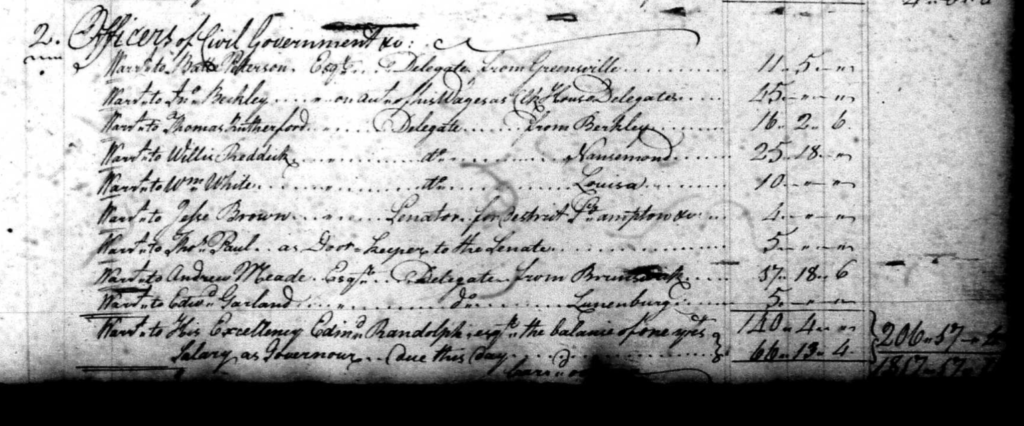

December 1 journal entry (£206 salary installment)

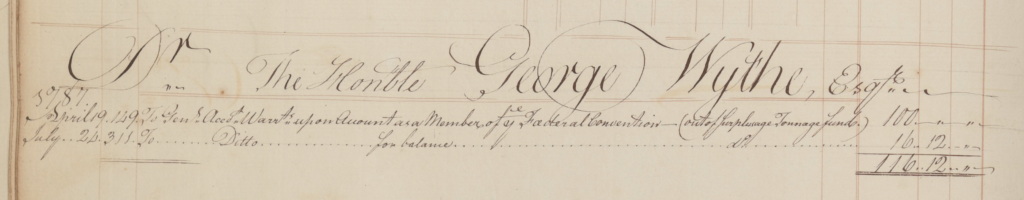

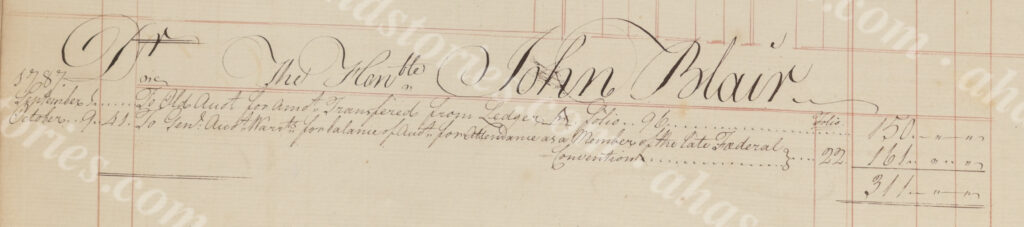

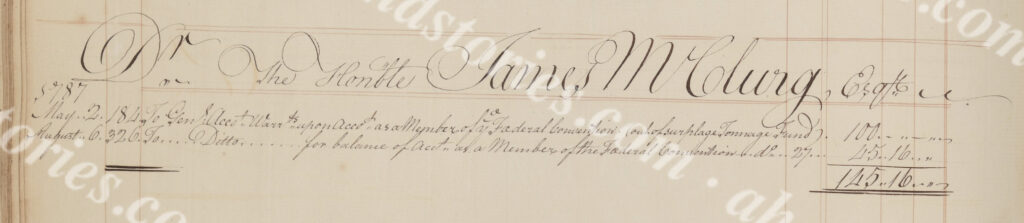

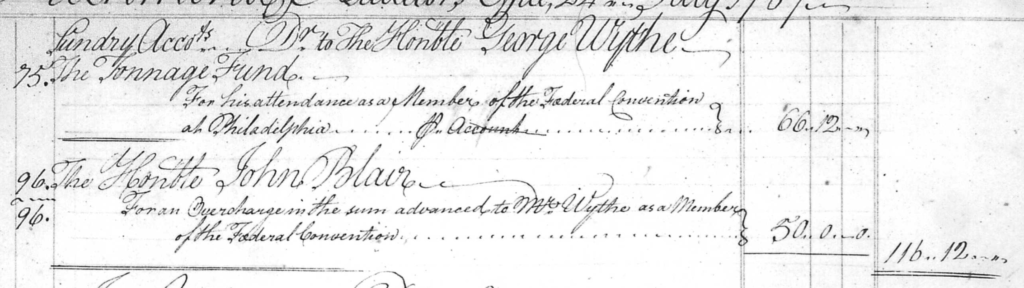

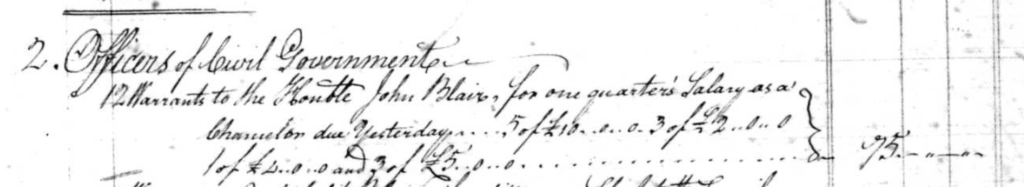

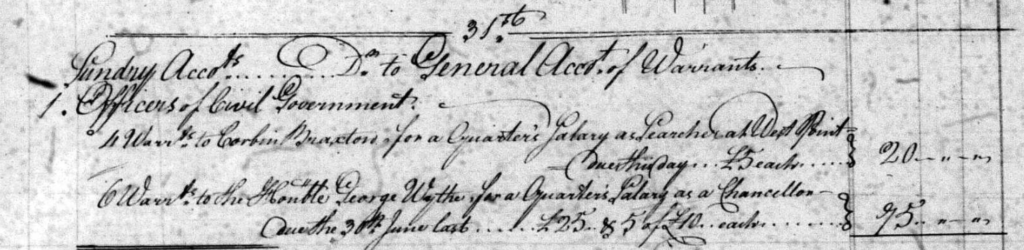

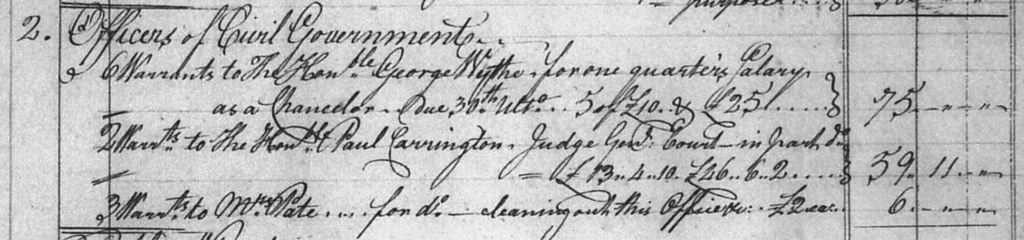

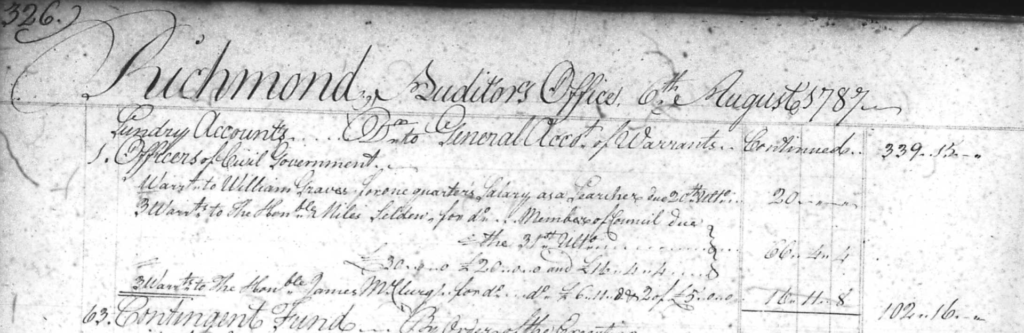

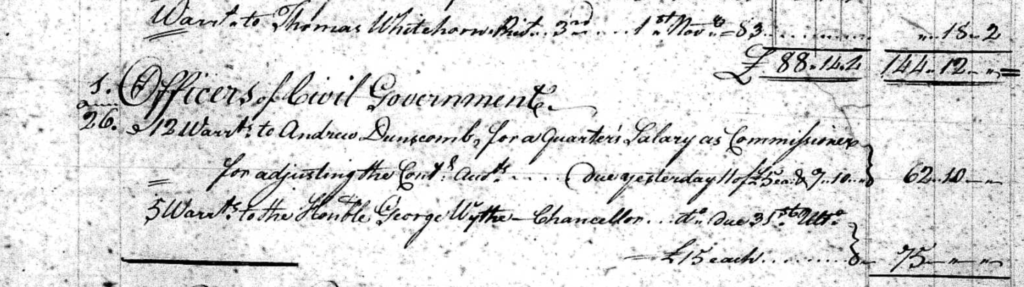

Wythe, Blair and McClurg:

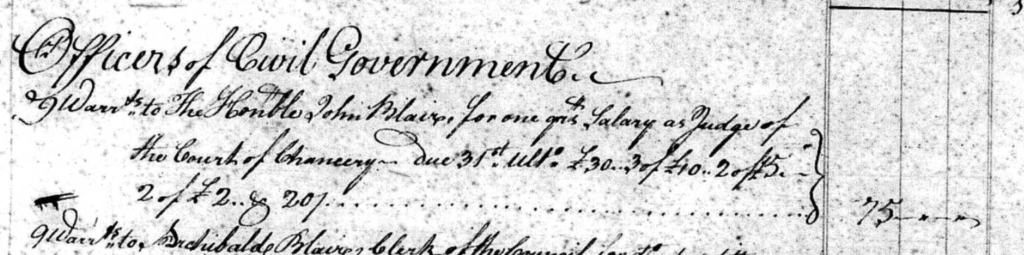

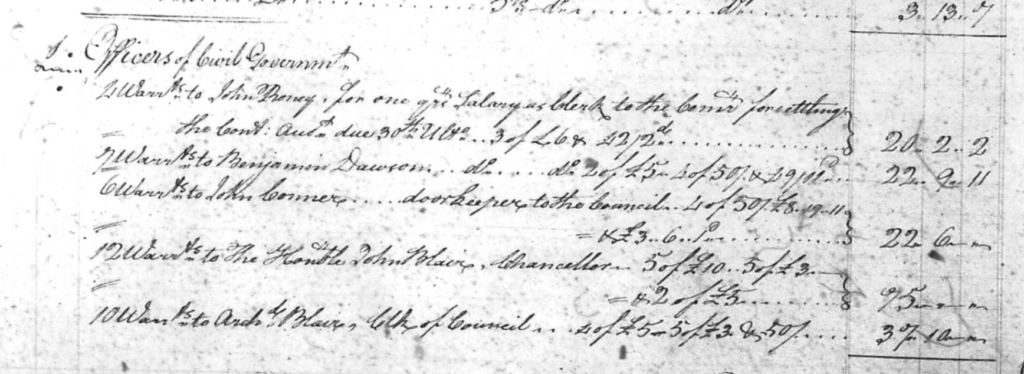

- Chancellors George Wythe and John Blair were judges on the Virginia Court of Chancery. Their annual salary was £300, paid in quarterly installments of £75. While it is not an obvious question, it appears that both Wythe and Blair were paid their judicial salary while they were serving in Philadelphia, even though they were not riding the circuit or holding court during the Convention.

- Due to his wife’s poor health, Wythe was forced to leave the Convention on or about June 6. Wythe left behind £50 of his £100 advance, to be used by the other delegates to cover their expenses.

- Dr. James McClurg was one of a half dozen members of the Governor’s Privy Council (also known as the Executive Council). The members of the Privy Council shared the £2,000 appropriated by the Legislature, which was allocated to the members based on their attendance.

- It is unclear whether George Wythe and James McClurg also received their pay as professors of law and medicine at the College of William and Mary.

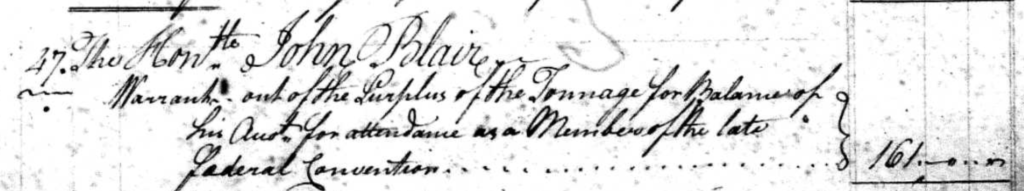

Ledgers showing Convention pay for Wythe, Blair and McClurg

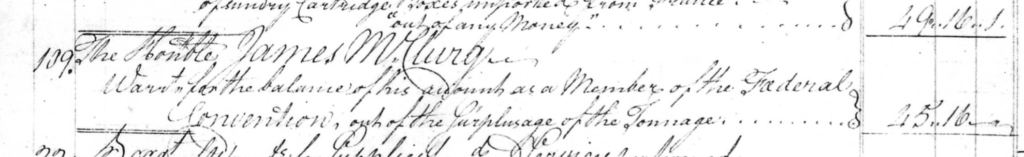

Journals reflecting additional Convention pay for Wythe, Blair and McClurg

July 24th

August 6

October 9

Journals showing salary for Wythe, Blair and McClurg

Blair’s judicial salary paid on April 6, July 3 and October 6:

Wythe’s judicial salary paid on April 12, July 31 and Oct 3

McClurg’s pay for service on the Privy Council (August 6 and November 1)

Dr. James McClurg, a medical doctor, was a member of the Governor’s Privy Council. Members of the Privy Council were not paid a salary. Instead, they were paid a per diem for each day that they attended Council meetings, which was similar to the method of compensating members of Congress.

This post continues with a supplemental discussion of the compensation paid to James Madison (Pending). Was James Madison, the hardest working delegate in Philadelphia, underpaid during the summer of 1787?

SOURCES AND ADDITIONAL READING:

Edmund Randolph, A Biography, John J. Reardon (1974)

Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution, Richard Beeman (2009)

Miracle at Philadelphia, Catherine Drinker Bowen (1966)

A Brilliant Solution: Inventing the American Constitution, Carol Berkin (2002)

The Summer of 1787: The Men who Invented the Constitution, David O. Stewart (2007)

The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Vol III, edited by Max Farrand (1911)

Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution, Richard Beeman (2009)

1787: The Day-to-Day Story of the Constitutional Convention, Anne Toogood, et al.(1987)