The Statute of Northampton, 2 Edw. 3, c. 3 (1328)

In the case of New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen the Supreme Court is examining the Second Amendment in connection with New York’s gun permitting requirements. Oral argument was held on November 3, in what could prove to be one of the most important Second Amendment decisions since the 2008 case of District of Columbia v. Heller. Over eighty amicus (friend of the court) briefs were filed in the Bruen case, several of which discuss the Statute of Northampton and English common law.

This post (Part I) is the first of a two-part discussion of the Second Amendment, the 2008 Heller decision and the pending Bruen case. This post discusses the Statute of Northampton and the background of the statute’s adoption during the reign of King Edward III. Part I also discusses the Game Act of 1671 which sought to limit poaching and restricted arms to the landed elite. It is noteworthy that the Game Act was adopted by Catholic King James II in connection with the disarmament of Protestant enemies, prior to the adoption of the English Bill of Rights.

Part II discusses justice of the peace manuals, the Justice of the Peace Act of 1361 (34 Edw. 3 c. 1), and Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. These authorities are cited in the Bruen briefs. Click here for a discussion of early American justice of the peace manuals.

In defending its strict firearm licensing requirements, the State of New York argued in its brief that “public carry laws predate the founding, tracing back to 14th-century England and 17th-century colonial America.” In particular, New York pointed to the Statute of Northampton, along with other “Northampton-style laws” providing that “no man great nor small … except the King’s servants in his presence” shall “go nor ride armed by night nor by day, in fairs, markets … nor in no part elsewhere” or “forfeit their armour … and their bodies to prison at the King’s pleasure.”

The Statute of Northampton was in turn adopted by several American colonies in the late 1700s. For example, in 1686 New Jersey became the first colony to codify a Northampton-style law providing that no person “shall presume privately to wear any pocket pistol… or other unusual or unlawful weapons,” and that “no planter shall ride or go armed with sword, pistol, or dagger.” Ch. 9, 1686 N.J. Laws 289, 290. Citing to the Statute of Northampton, New York argues that “[u]nder founding-era laws, as under the English laws from which they derived, ‘constables, magistrates, or justices of the peace had the authority to arrest anyone who traveled armed.’ “

From medieval England onward, local sheriffs and magistrates have been entrusted with the “power to execute” public carry restrictions. 2 Edw. 3, c. 3 (1328); see also Ch. 21, 1786, Va. Acts at 33; Mass. Rev. Stat. ch. 134, § 16. And that power included determining when public arms-carrying would be permitted and how to punish offenders.

Gun-rights advocates, by contrast, minimize the Statute of Northampton and argue it was only intended to restrict “dangerous and unusual weapons” that would “terrify” the public (carrying arms when done in terrorem populi). The petitioners and their amici therefore disagree that there was a 700 year tradition of restricting weapons in public spaces. They also argue that offenses under the Statute of Northampton were rarely prosecuted and that the statute had fallen into desuetude (meaning that the law had lost its legitimacy).

New York and its amici respond that the Statute of Northampton contained only narrow exceptions for the “King’s Servants,” “Ministers,” and “Precepts.” They argue further that other historical sources, including justice of the peace manuals, establish that going armed in public was generally forbidden. These authorities are discussed in Part II (pending).

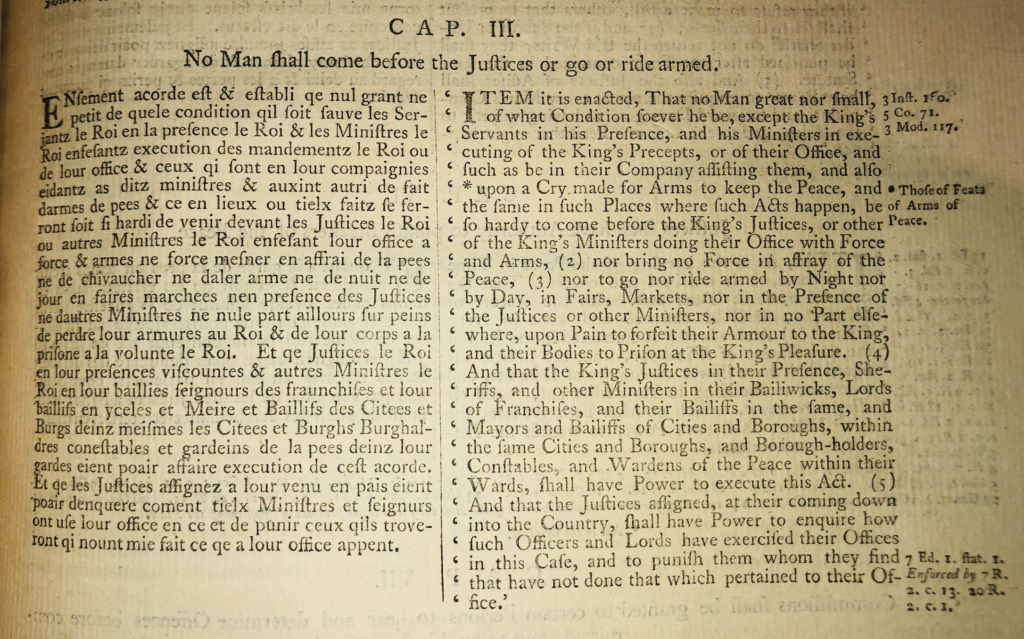

Thus, the 14th century Statute of Northampton has become a focal point of the debate over the “preexisting right” to bear arms that is codified in the 2nd Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Statute of Northampton, 2 Edw. 3, c. 3 (1328), is pictured below and provides in its entirety as follows:

Item, it is enacted, that no man great nor small, of what condition soever he be, except the king’s servants in his presence, and his ministers in executing of the king’s precepts, or of their office, and such as be in their company assisting them, and also [upon a cry made for arms to keep the peace, and the same in such places where such acts happen,] be so hardy to come before the King’s justices, or other of the King’s ministers doing their office, with force and arms, nor bring no force in affray of the peace, nor to go nor ride armed by night nor by day, in fairs, markets, nor in the presence of the justices or other ministers, nor in no part elsewhere, upon pain to forfeit their armour to the King, and their bodies to prison at the King’s pleasure. And that the King’s justices in their presence, sheriffs, and other ministers in their bailiwicks, lords of franchises, and their bailiffs in the same, and mayors and bailiffs of cities and boroughs, within the same cities and boroughs, and borough-holders, constables, and wardens of the peace within their wards, shall have power to execute this act. And that the justices assigned, at their coming down into the country, shall have power to enquire how such officers and lords have exercised their offices in this case, and to punish them whom they find that have not done that which pertained to their office.

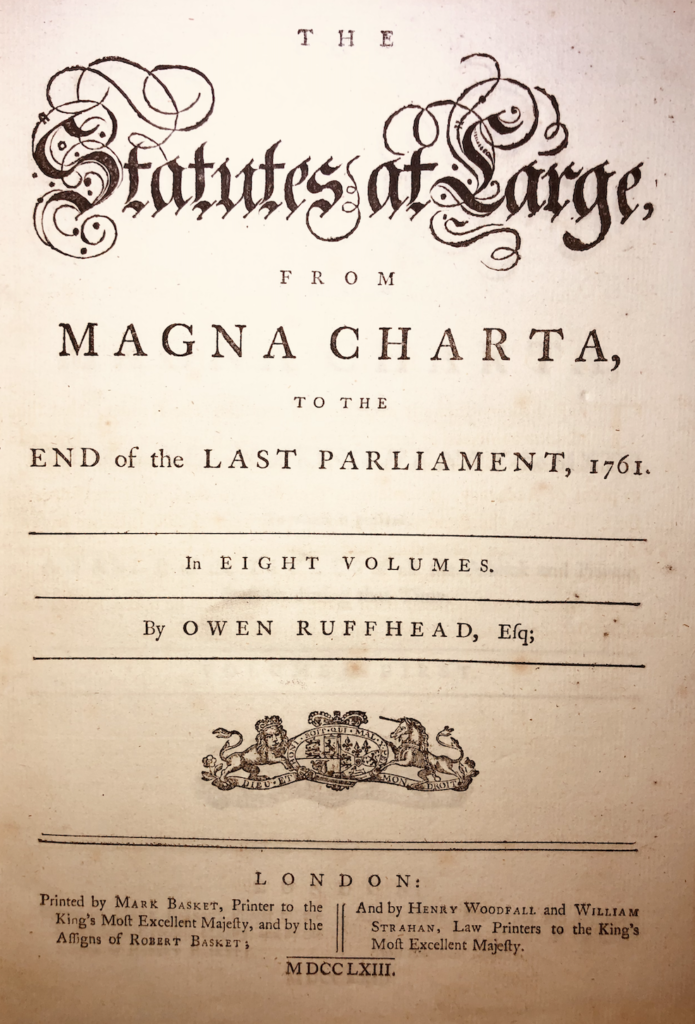

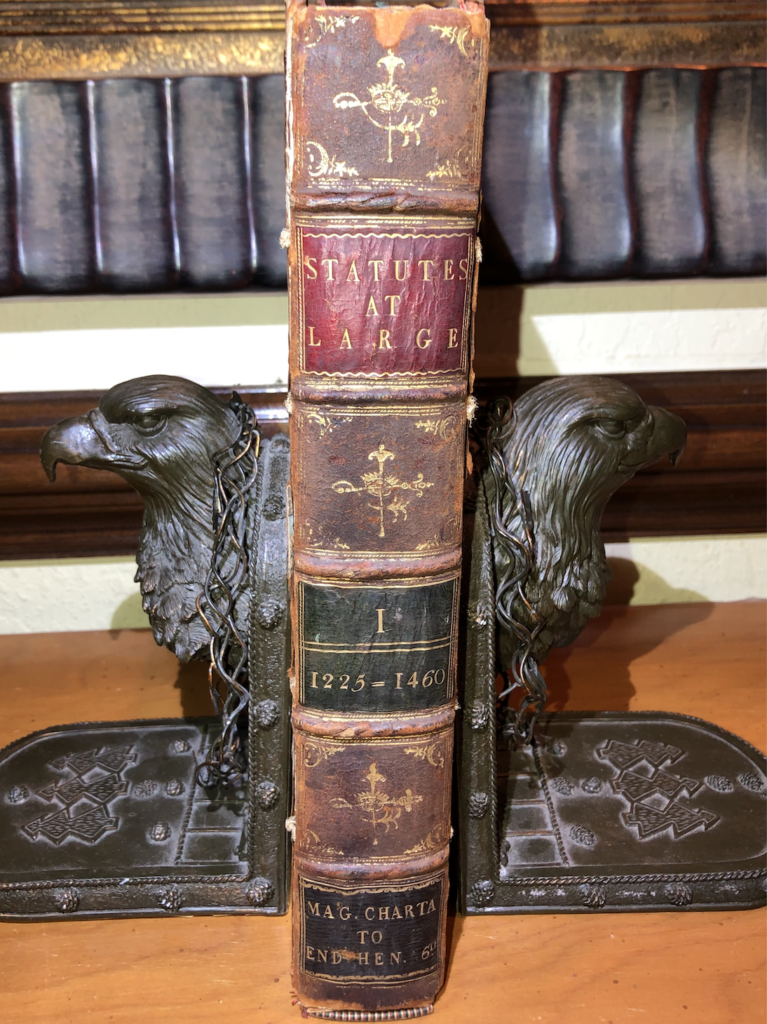

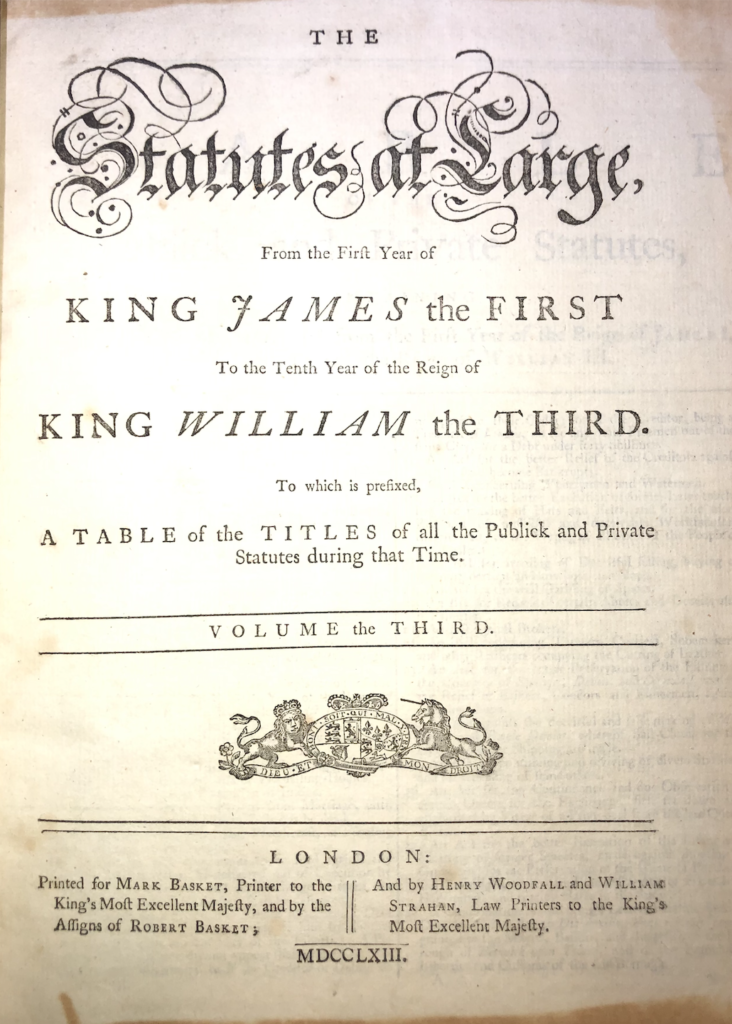

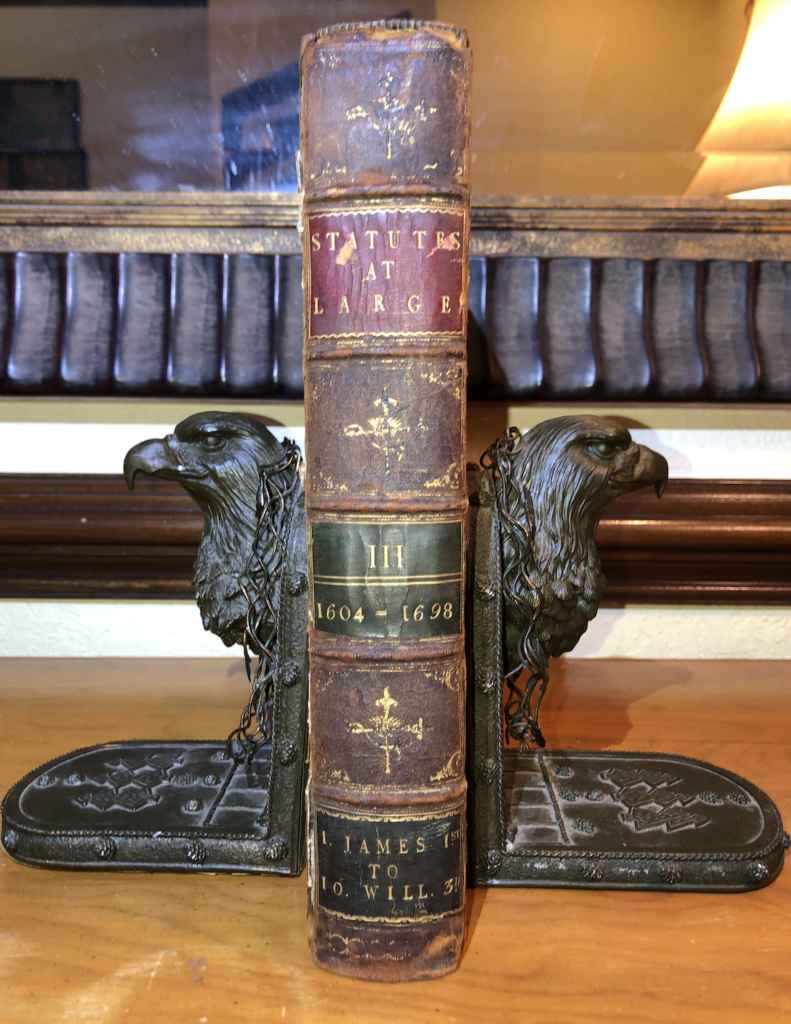

Pictured below is the title page and spine of volume I of the Statutes at Large in eight volumes published by Owen Ruffhead in 1763. The Statute of Northampton pictured above can be found on page 197 in this statutory codification by Ruffhead.

Justice Scalia’s majority opinion in Heller

The 2008 Heller case struck down Washington D.C.’s strict gun-control ordinance holding in a 5-4 decision that law-abiding residents had a right to keep a handgun at home for self defense. Writing the majority opinion, Justice Scalia concluded that the Second Amendment guaranteed an individual right to possess and carry weapons.

According to Scalia, this interpretation “is strongly confirmed by the historical background of the Second Amendment.” Scalia further explains that “it has always been widely understood that the Second Amendment, like the First and Fourth Amendments, codified a pre-existing right” that was brought from England to the American colonies. In Scalia’s analysis, by the time that the United States was founded, “the right to have arms had become fundamental for English subjects.”

For Scalia, “[t]he very text of the Second Amendment implicitly recognizes the pre-existence of the right and declares only that it ‘shall not be infringed.’ ” For this reason, the Statute of Northampton and the history of English common law are releavant in the American courts when interpreting the Second Amendment and the Bill of Rights.

In a dissenting opinion in Heller, Justice John Paul Stevens argued that the Second Amendment does not create an unlimited right to bear arms. According to Stevens’ reading of the the Second Amendment, it merely protects the right to bear arms for certain military purposes and does not limit the government’s power to regulate nonmilitary use and ownership of guns. For Stevens and other dissenting justices, it is critical to give meaning to the introductory clause of the Second Amendment which explains its purpose that “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State . . . .”

Reign of Edward III and the 100 Years’ War

The Statute of Northhampton was adopted during the second year of Edward III’s reign as the of King England and “Lord of Ireland” from 1327 to 1377. King Edward III was known for his restoration of royal authority following his father’s chaotic rule. Edward’s fifty-year reign was the second longest in medieval English history, during which England became one of the most powerful military powers in Europe.

Edward was crowned King at the age of 14 after his father was deposed by his mother, Isabella of France, and her consort, Roger Mortimer. Three years later, at age seventeen, Edward led a successful coup d’etat against Mortimer, who was the de facto ruler. In 1337, after victories in Scotland, Edward declared himslf the rightful heir of the French throne, initiating the Hundred Years’ War between the English House of Plantagenet and the French House of Valois.

In 1348, during the Hundred Years’ War, the Black Plague (also known as the Black Death or Bubonic Plague) ravaged across England, killing one third of the population. Military operations would resume in earnest in the mid-1350’s, when Edward’s oldest son, Edward, Price of Wales captured King John II of France. Edward III would subsequently renounce his claims on the French throne, but retain and extend his sovereignty over his possessions in France.

King Edward and Parliament

Several notable laws were adopted during Edward’s reign including: 1) the Treason Act of 1351 (25 Edw. 3, St. 5 c. 2) which codified and defined the common law offense of treason; 2) the Statutes of Provisors and Benefices (25 Edw. 3) limiting Papal authority in England; 3) the Justice of the Peace Act of 1361 (34 Edw. 3 c. 1); and 4) the Statute of Northhampton discussed above.

The Justice of the Peace Act of 1361 governed who was eligble to become a Justice of the Peace and defined their duties and powers. The Act provided for the selection in each county of a lord and three to four worthy people to be justices of the peace, responsible for dealing with “offenders, rioters, and all other barators.” While the role of the justices of the peace was not new, the 1361 Act helped perpetuate and empower the institution, particularly at a time when Parliament was concerned about soliders returning from war in France. Part II (pending) contains an expanded discussion of the Justice of the Peace Act.

Edward’s reign is also notable for the evolution of Parliament, which developed into a bicameral body composed of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. In 1376 the “Good Parliament” achieved the first recorded impeachment, of William Latimer, who was eventually pardoned by the King. The office of Speaker emerged near the end of Edward’s rule, with Sir Peter de la Mare being selected by the Commons as its spokesman before the elderly Edward III.

Due to labor shortages resulting from the Black Plague, Parliament enacted the Statute of Labourers of 1351 (23 Edw. 3). The law limited peasant mobility and attempted to fix wages at pre-plague levels. Not surprisingly, the law failed in its effort to control the law of supply and demand. Nevertheless, Edward III is widely regarded as a highly popular and successful king. The 14th century Jean Froissart compared Edward III to King Arthur, writing in Froissart’s Chronicles that, “[h]is like had not been seen since the days of King Arthur.”

Game Act of 1671

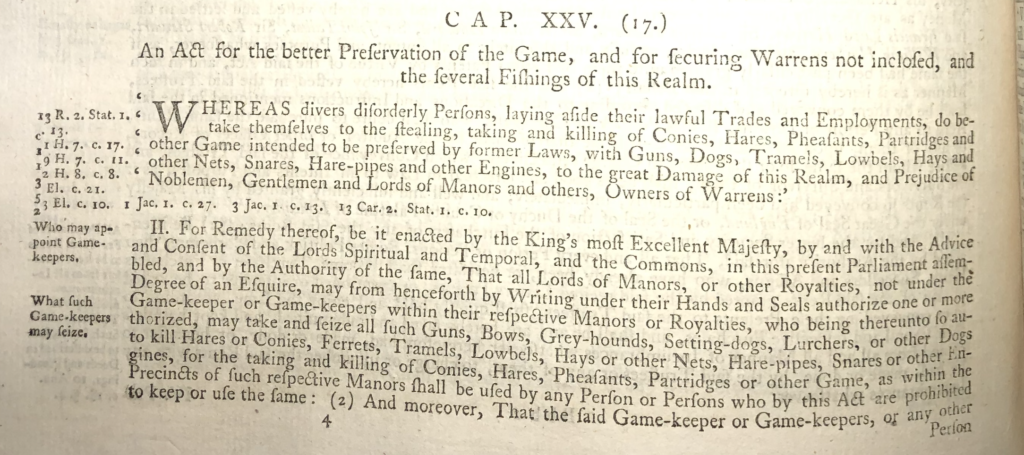

The Game Act of 1671, otherwise known as “An Act for the better preservation of the Game, and for secureing Warrens not inclosed, and the severall Fishings of this Realme,” was adopted during the reign of King James II. James was deposed during the Glorious Revolution in 1688 and replaced with William III and Mary II, due in part to his embrace of Catholicism. The whereas clause of the detailed nine section Act explained that “diverse disorderly persons … doe betake themselves to the stealing, takeing and killing of Conies, Hares, Pheasants, Partridges and other Game, intended to be preserved by former Lawes, with Guns, Dogs, Tramells, Lowbells, Hayes, and other Netts, Snares, Hare-pipes and other Engines, to the great dammage of this Realme, and prejudice of Noblemen, Gentlemen and Lords of Mannours and others Owners of Warrens.”

Section II of the Act is set forth above authorized the appointment of gameskeepers with the power to seize weapons and search houses for guns and other weapons:

II. What Persons are prohibited the keeping of Guns, Bows, Dogs, &c.

And it is hereby enacted and declared That all and every person and persons, not haveing Lands and Tenements or some other Estate of Inheritance in his owne or his Wifes right of the cleare yearely value of one hundred pounds per ann? or for terme of life, or haveing Lease or Leases of ninety nine yeares or for any longer terme, of the cleare yearely value of one hundred and fifty pounds, other then the Sonne and Heire apparent of an Esquire, or other person of higher degree, and the Owners and Keepers of Forrests, Parks, Chases or Warrens, being stocked with Deere or Conies for their necessary use in respect of the said Forrests, Parks, Chases or Warrens, are hereby declared to be persons by the Lawes of this Realme, not allowed to have or keepe for themselves or any other person or persons any Guns, Bowes, Grey hounds, Setting-dogs, Ferretts, Cony-doggs, Lurchers, Hayes, Netts, Lowbells, Hare-pipes, Ginns, Snares or other Engines aforesaid, But shall be, and are hereby prohibited to have, keepe or use the same.

Additional reading:

Scotusblog.com: New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen

Amicus brief of 17 preeminent professor of English and American history in support of Respondents