History of the office of Justice of the Peace:

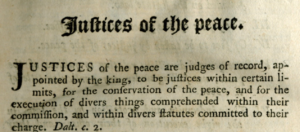

The position of justice of the peace (“JP”) was officially created in 1360 in England with the adoption of the Justice of the Peace Act (34 Ed. III, ch. 1). Some historians date the position back even further to the reign of Richard the Lion-Hearted (1189-1199), when knights crossed the kingdom and preserved the king’s peace. The Justice of the Peace Act of 1360 empowered justices of the peace to try and imprison “offenders, rioters, and all other barators” (a barator was a brawler). In England, the JP’s jurisdiction gradually expanded as political power moved from lords of the manor to the landed gentry. By the 1600s local governmental functions were firmly rooted in justices of the peace (also known as “magistrates” or “commissioners”).

The position of justice of the peace (“JP”) was officially created in 1360 in England with the adoption of the Justice of the Peace Act (34 Ed. III, ch. 1). Some historians date the position back even further to the reign of Richard the Lion-Hearted (1189-1199), when knights crossed the kingdom and preserved the king’s peace. The Justice of the Peace Act of 1360 empowered justices of the peace to try and imprison “offenders, rioters, and all other barators” (a barator was a brawler). In England, the JP’s jurisdiction gradually expanded as political power moved from lords of the manor to the landed gentry. By the 1600s local governmental functions were firmly rooted in justices of the peace (also known as “magistrates” or “commissioners”).

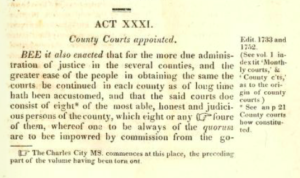

The English tradition of local control overseen by the county justice of the peace was transplanted to America. For example, in 1662 Virginia adopted Act XXXI (II Hening 69) which empowered justices of the peace to act according to the laws of England and “doe all such things as by the laws of England are to be done by justices of the peace there.” The 1662 Act further provided that justices of the peace should be “of the most able, honest and judicious persons in the county.” The County Court in each county county consisted of eight justices of the peace, any four of which would constitute a quorum to hold court.

The English tradition of local control overseen by the county justice of the peace was transplanted to America. For example, in 1662 Virginia adopted Act XXXI (II Hening 69) which empowered justices of the peace to act according to the laws of England and “doe all such things as by the laws of England are to be done by justices of the peace there.” The 1662 Act further provided that justices of the peace should be “of the most able, honest and judicious persons in the county.” The County Court in each county county consisted of eight justices of the peace, any four of which would constitute a quorum to hold court.

In colonial America JPs exercised both judicial and administrative powers, making justices of the peace among the most important public offices in their day. As in England, the office was reserved for “men of means and standing.” A major difference, however, between the colonial justices and their English counterparts was jurisdictional. English justices lacked jurisdiction in civil matters, but sat as a “court of record” in criminal matters. Colonial justices had wide civil jurisdiction and also sat as a “court of record” in criminal cases. Compared with their northern counterparts, southern justices of the peace had additional powers pursuant to odious slave codes.

In colonial America JPs exercised both judicial and administrative powers, making justices of the peace among the most important public offices in their day. As in England, the office was reserved for “men of means and standing.” A major difference, however, between the colonial justices and their English counterparts was jurisdictional. English justices lacked jurisdiction in civil matters, but sat as a “court of record” in criminal matters. Colonial justices had wide civil jurisdiction and also sat as a “court of record” in criminal cases. Compared with their northern counterparts, southern justices of the peace had additional powers pursuant to odious slave codes.

Justices of the peace were responsible for maintaining order in the community as the arresting and arraigning magistrate. JPs also watched over the morals of the community (ranging from drunkenness, gaming, and adultery to property crimes). In their administrative role they also authenticated deeds and affidavits, were empowered to officiate marriage ceremonies, and raised the “hue and cry” against escaped prisoners.

Legal publications in colonial America:

Prior to the American Revolution, the overwhelming majority of law books in the colonies were English legal texts, treatises and other authorities. There were few formally trained lawyers and publication of law books was expensive. Distinctly American jurists and authors would gradually emerge following the Revolutionary War as the country established its own laws, legal precedents, and caselaw. For example, click here for to a discussion of Connecticut jurist Zephaniah Swift’s early works.

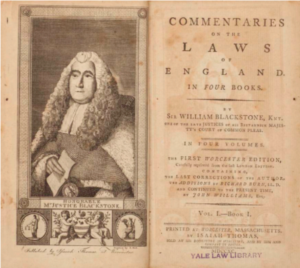

Nevertheless, at the turn of the 18th Century, American lawyers primarily relied on English legal texts (and Americanized editions of English publications). For example, in 1790 Isaiah Thomas published the first post-war American edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Click here for a discussion of Isaiah Thomas’ publications, including Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Interestingly, Blackstone’s personal opposition to American independence did not curb demand for his classic work. Joseph Story, who would later be appointed to the United States Supreme Court, became a leader in the movement to republish Americanized versions of leading English works.

Nevertheless, at the turn of the 18th Century, American lawyers primarily relied on English legal texts (and Americanized editions of English publications). For example, in 1790 Isaiah Thomas published the first post-war American edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Click here for a discussion of Isaiah Thomas’ publications, including Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Interestingly, Blackstone’s personal opposition to American independence did not curb demand for his classic work. Joseph Story, who would later be appointed to the United States Supreme Court, became a leader in the movement to republish Americanized versions of leading English works.

Justices of the Peace Manuals:

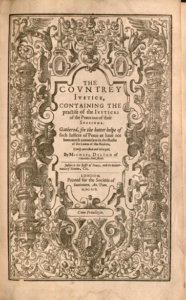

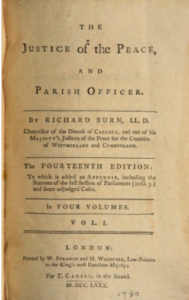

Another important resource for American lawyers and governmental officials, were manuals, form books and legal handbooks for justices of the peace. One of the most commonly used English legal manuals was Richard Burn’s The Justice of the Peace published in England in 1755. Burn’s Justice, as it was informally known, went through multiple editions and became the standard manual used in the colonies in the 18th century prior to independence. Click here for a link to the 14th edition of Burns’ Justice (1780). Burn’s Justice built upon Michael Dalton’s The Countrey Justice: Containing the Practise of the Justices of the Ceace out of their Sessions (London, 1619), which itself was republished in twenty updated editions over time.

Another important resource for American lawyers and governmental officials, were manuals, form books and legal handbooks for justices of the peace. One of the most commonly used English legal manuals was Richard Burn’s The Justice of the Peace published in England in 1755. Burn’s Justice, as it was informally known, went through multiple editions and became the standard manual used in the colonies in the 18th century prior to independence. Click here for a link to the 14th edition of Burns’ Justice (1780). Burn’s Justice built upon Michael Dalton’s The Countrey Justice: Containing the Practise of the Justices of the Ceace out of their Sessions (London, 1619), which itself was republished in twenty updated editions over time.

Justices of the peace manuals were among the earliest “American” works to be published in the colonies. The first colonial JP manual was George Webb’s The Office and Authority of a Justice of Peace and also the Duty of Sheriffs, published in 1736. Webb’s Justice heavily relied on earlier English works, but included specific citations to Virginia law. Among the duties of a Virginia justice were regulation of hunting, hog-stealing, Indians, runaways, servants, slaves and tobacco. A Virginia JP was also charged with enforcing laws concerning adultery, bastardy, bigamy, defamation of public officials, blasphemy, and interracial marriage. Relying heavily on Webb’s manual, in 1774 James Davis published the first JP manual for North Carolina justices, The Office and Authority of a Justice of Peace.

After the Revolutionary War a void was created for updated American manuals for justices of the peace, town officers and public officials. As a practical matter, the new federal government was far removed from the lives of average Americans – who were far more likely to interact with their local government than federal officials.

Unlike today, local justices of the peace played an important role in both government administration and the adjudication of legal disputes. In fact, from 1760-1774 George Washington served as a justice of the peace in Fairfax County, Virginia. Washington followed in the footsteps of his father (who was also a sheriff), grandfather, and great grandfather who were also justices of the peace. Like Washington, Thomas Jefferson was also a member of the landed planter class in Virginia. Jefferson and his father both served as justices of the peace. Thomas Jefferson’s library contained the Webb, Burns, and Hening’s JP manuals. Click here to review Jefferson’s extensive book collection.

Unlike today, local justices of the peace played an important role in both government administration and the adjudication of legal disputes. In fact, from 1760-1774 George Washington served as a justice of the peace in Fairfax County, Virginia. Washington followed in the footsteps of his father (who was also a sheriff), grandfather, and great grandfather who were also justices of the peace. Like Washington, Thomas Jefferson was also a member of the landed planter class in Virginia. Jefferson and his father both served as justices of the peace. Thomas Jefferson’s library contained the Webb, Burns, and Hening’s JP manuals. Click here to review Jefferson’s extensive book collection.

Although justices of the peace were commonly drawn from elite circles in the community, many lacked formal legal training. As a result, manuals for justices of the peace were necessary tools of the trade. By way of example, Jefferson was a highly trained lawyer. Washington wasn’t.

Justices of the peace had wide ranging duties, particularly in less developed, rural counties. While the position was originally created to enforce the “king’s peace,” as suggested by its name, the job grew in scope and importance during the Middle Ages. In colonial America JPs adjudicated and tried minor offenses and were responsible for pre-trial aspects of more serious crimes, including arrest, investigation and arraignment.

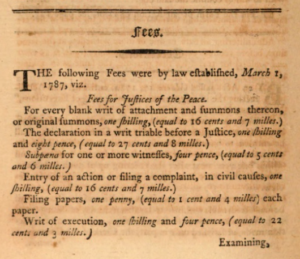

In England JPs were drawn from the economic elite, the landed gentry, and successful merchants and clergy in the cites. In the colonies, justices of the peace were generally appointed by the colonial governor from the planter class and served without compensation, particularly in the South. This practice carried over to Virginia’s Constitution of 1776. After the Revolutionary War, justices of the peace became more professionalized and the fees they could charge were increasingly specified by law.

In England JPs were drawn from the economic elite, the landed gentry, and successful merchants and clergy in the cites. In the colonies, justices of the peace were generally appointed by the colonial governor from the planter class and served without compensation, particularly in the South. This practice carried over to Virginia’s Constitution of 1776. After the Revolutionary War, justices of the peace became more professionalized and the fees they could charge were increasingly specified by law.

Freeman’s Massachusetts Justice and Hening’s New Virginia Justice – American manuals written by Americans for Americans:

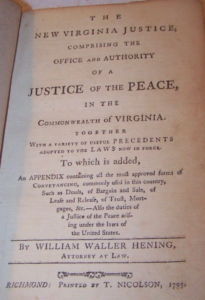

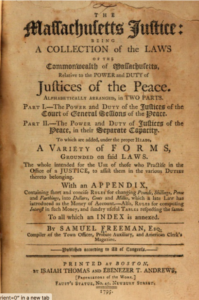

Two examples of popular JP manuals following the adoption of the U.S. Constitution were Samuel Freeman’s THE MASSACHUSETTS JUSTICE: Being a Collection of the Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts relative to the Power and Duty of Justices of the Peace (Samuel Freeman, published by Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer Andrews, 1795) and William Hening’s THE NEW VIRGINIA JUSTICE, Comprising the Office and Authority of a Justice of the Peace, in the Commonwealth of Virginia, together with a Variety to Useful Precedents Adopted to the Laws Now in Force (William Waller Hening, published by T. Nicolson, 1795). Click here for further discussion of Hening’s extraordinary career and other publications.

Two examples of popular JP manuals following the adoption of the U.S. Constitution were Samuel Freeman’s THE MASSACHUSETTS JUSTICE: Being a Collection of the Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts relative to the Power and Duty of Justices of the Peace (Samuel Freeman, published by Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer Andrews, 1795) and William Hening’s THE NEW VIRGINIA JUSTICE, Comprising the Office and Authority of a Justice of the Peace, in the Commonwealth of Virginia, together with a Variety to Useful Precedents Adopted to the Laws Now in Force (William Waller Hening, published by T. Nicolson, 1795). Click here for further discussion of Hening’s extraordinary career and other publications.

Henning’s New Virginia Justice codified and updated the traditional JP provisions but also provided valuable information for the legal and business community, including two well received appendices. In particular, the first appendix addressed the duties of a justice under the laws of the United States. Hening took care to minimize the use of Latin jargon and phrases. Thus, he continued a trend of democratization of the law the Webb had begun in 1736. However, by 1795 Webb’s Justice was obsolete. Hening also included an “explanation of law terms” section, which was effectively a mini-legal dictionary explaining fifty-eight legal phrases and abbreviations. Click here for a link to Hening’s explanation of legal terms.

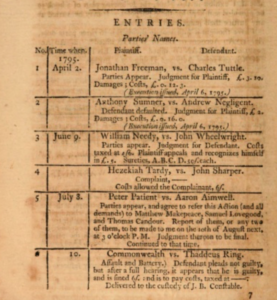

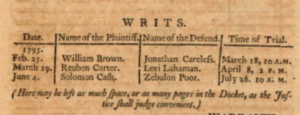

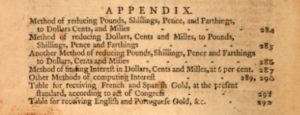

While Freeman’s Massachusetts Justice did not address federal law, it was an effort to codify and update the law and forms for Massachusetts justices of the peace. Freeman also provided a separate appendix of practical tables and charts, including instructions on how to convert Pounds, Shillings, Pence and Farthings into Dollars and Cents. Interestingly, in 1795 the conversion of French, Spanish and Portuguese gold warranted inclusion in the appendix for Americans justices. Freeman’s colorful examples of docket entries are also noteworthy. Notice below how “Solomon Cash” (spelled “Cafh” before Noah Webster’s spellings were universally accepted) is suing “Zebulon Poor.” Other parties include plaintiff “Hezeliah Tardy” and defendants “Andrew Negligent,” “Aaron Aimwell,” and “Hannah Heedless” who was prosecuted for the crime of fornication.

Other Justice of the Peace Manuals:

In colonial Virginia alone, historians have documented at least nineteen different justice of the peace manuals found in the libraries of colonial Virginians, including Thomas Jefferson.

The following list illustrates the ubiquity of JP manuals which proliferated in the late 18th Century and early 19th Century in the new United States: James Parker’s Conductor Centralis (N. Y. 1787); John F. Grimke’s Justices of the Peace (S. C. 1796); Francis X. Martin’s Office of Justice of the Peace (N. C. 1791), Jurisdiction of Justices of the Peace in Civil Suits (N. C. 1796), and Powers and Duties of Sheriff (N. C. 1806); Ewing’s Justice of Peace (N. J. 1805); Justices and Constables’ Assistant, by W. Graydon (Philadelphia, 1805); R. Bache’s Manual of Pennsylvania Justices of the Peace (Philadelphia, 1810, 1814); C. Read’s Precedents in Office of Justice of Peace and Short system of Convey ancing (Philadelphia, 1794, 1801); Samuel Whiting’s Connecticut Town Officer (1814); The Civil Officer (Boston, 1809, 1814); John Tappan’s County and Town Officers of New York (Kingston, N. Y. 1816); Rodolphus Dickinson’s Powers of Sheriff (Mass. 1810); Jonathan Leavitt’s Poor Law of Massachusetts (Mass. 1810); Probate Directory (Mass. 1812); Overseers Guide (Mass. 1815).

Marbury v. Madison:

One of the most famous cases in American history and certainly one of the most important, Marbury v. Madison, involves a dispute over the appointment of a justice of the peace, William Marbury. In the final days of John Adams’ administration, the lame duck federalist Congress adopted An Act Concerning the District of Columbia, Chapter XV, s. 11; 2 Stat. 103, 107 (1801) creating numerous appointments to be filled by Adams.

President Adams included Marbury among the twenty-three names he sent to the Senate as justices of the peace for Washington County. While Marbury’s appointment was confirmed by the Senate, his commission was not delivered by the incoming Secretary of State, James Madison. The rest of the story is history. Click here to read more about the Judiciary Act of 1801 and the Midnight Justices, including Justices of the Peace.

Additional reading and sources:

Esteemed Bookes of Lawe and the Legal Culture of Early Virginia (edited by Billings & Tarter, 2017)

Law Books in Action: Essays on the Anglo-American Treatise (edited by Frenandez & Dubber, 2012)