1790 – ACT PROVING FOR MORE EFFECTIVE COLLECTION OF DUTIES

(Hamilton creates the Coast Guard)

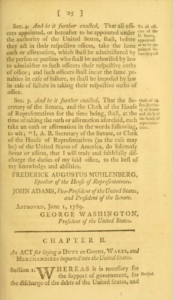

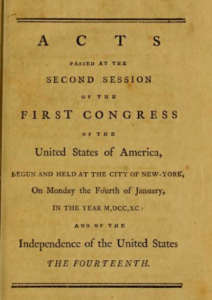

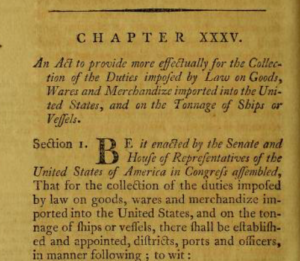

“An Act to provide more effectually for the collection of the duties imposed by law on goods, wares and merchandise imported into the United States, and on the tonnage of ships or vessels”

[First Congress, 2nd Sess., Chapter XXXV] Click here for a link to the Act.

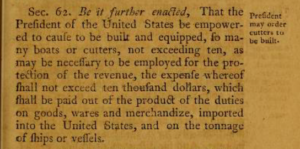

On August 4, 1790, Congress adopted the detailed proposals recommended by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton to more effectively collect the needed import duties that would be the primary source of revenue for the Federal government. Sections 62 through 65 of the Act authorized Hamilton to build ten boats (revenue cutters) to enforce the new tariffs, which had been adopted a year earlier on July 4, 1789. The resulting fleet would become known as the “Cutter Service,” also known as the “Revenue Marine.”

On August 4, 1790, Congress adopted the detailed proposals recommended by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton to more effectively collect the needed import duties that would be the primary source of revenue for the Federal government. Sections 62 through 65 of the Act authorized Hamilton to build ten boats (revenue cutters) to enforce the new tariffs, which had been adopted a year earlier on July 4, 1789. The resulting fleet would become known as the “Cutter Service,” also known as the “Revenue Marine.”

August 7 is now officially celebrated as the birthday of the Coast Guard, which was initially placed under the jurisdiction of the Treasury Department. After the Continental Navy was disbanded after the Revolutionary War, until 1798 when the United States Navy was created, the Treasury’s cutter service was the nation’s only naval force. The first cutter, the Massachusetts, was commissioned in 1791 in Newburry, Massachusetts. The program was so successful that three years later, in June of 1794, the Third Congress authorized construction of ten more cutters.

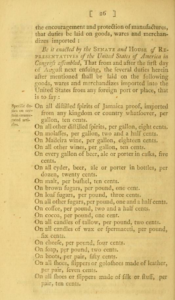

The first substantive act of Congress imposing tariffs on imports was adopted on July 4, 1789. The Tariff Act of 1789 (First Congress, 1st Session, Chapter II) recognized that its was necessary to discharge the debts of the United States and encourage the production of manufactures. The Tariff imposed duties on broad categories of imported goods, ranging from commodities to manufactured goods. The Tariff was accompanied by an “Act imposing Duties on Tonnage,” (First Congress, 1st Session, Chapter III) which imposed a tax of 6 cents per ton on American ships and 50 cents per ton on foreign ships.

Need and Role for the Coast Guard: On his second day in office as the first Secretary of Treasury, Hamilton issued a circular to all customs agents requesting exact figures of the duties collected in each state. When the reported revenue was suspiciously low, Hamilton realized that “guard boats” were necessary to curtail widespread smuggling. In his Report to Congress of April 22, 1790 Hamilton explained the reasons why ten boats were needed for “securing the collection of the revenue” at a time when 90% of federal revenue would be coming from tariffs and related import duties. Hamilton indicated that the majority of Merchants would comply with the law, but he wanted to guard against the “fraudulent few” who would not.

Need and Role for the Coast Guard: On his second day in office as the first Secretary of Treasury, Hamilton issued a circular to all customs agents requesting exact figures of the duties collected in each state. When the reported revenue was suspiciously low, Hamilton realized that “guard boats” were necessary to curtail widespread smuggling. In his Report to Congress of April 22, 1790 Hamilton explained the reasons why ten boats were needed for “securing the collection of the revenue” at a time when 90% of federal revenue would be coming from tariffs and related import duties. Hamilton indicated that the majority of Merchants would comply with the law, but he wanted to guard against the “fraudulent few” who would not.

According to Hamilton:

Justice to the body of the Merchants of the United States, demands an acknowlegment, that they have very generally manifested a disposition to conform to the national laws, which does them honor, and authorises confidence in their probity. But every considerate member of that body, knows, that this confidence admits of exceptions, and that it is essentially the interest of the greater number, that every possible guard should be set on the fraudulent few; which does not in fact tend to the embarassment of trade.

Hamilton described in painstaking detail the job duties for the proposed Coast Guard, including the need to “ply along” the coasts and harbors. Three years earlier, in Federalist 12, Hamilton had argued that “[a] few armed vessels, judiciously stationed at the entrances of our ports, might at a small expense be made useful sentinels of the laws.” Before he immigrated to America from the Carribean, Hamilton had experience with international trade which potentially provided useful background for his role as the first Secretary of Treasury. With regard to the professionalism and fidelity of the Coast Guard, Hamilton’s experiences as the aide-de-camp to George Washington during the Revolutionary War no doubt informed his thinking. Hamilton explained:

The utility of an establishment of this nature must depend on the exertion, vigilance and fidelity of those, to whom the charge of the boats shall be confided. If these are not respectable characters, they will rather serve to screen, than detect fraud. To procure such, a liberal compensation must be given, and in addition to this, it will, in the opinion of the Secretary, be adviseable, that they be commissioned as Officers of the Navy. This will not only induce fit men the more readily to engage, but will attach them to their duty by a nicer sense of honor.

Hamilton was also mindful of public perceptions when he outlined the rigorous standards of conduct that he expected for the Coast Guard. He cautioned cutter officers to “always keep in mind that their countrymen are free men and as such are impatient of everything that bears the least mark of a domineering spirit.” Hamilton advised the Guard to “refrain from whatever has the semblance of haughtiness, rudeness or insult.” Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow has written that Hamilton’s policies were so “masterfully” written that his directive about boarding foreign vessels was still in effect during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962.

Sections 62-65 of the Act specified that the cutter officers would have the authority to board every ship or vessel which shall arrive within the United States or within four leagues of the coast. Other duties included searching and examining ships and their manifests and placing “proper fastenings” on the hatches until they arrive at their places of destination. These precautions were designed to prevent smuggling, which had been rampant during the colonial period. Without the cutter fleet, smugglers were able to unload their cargoes on smaller “coaster” vessels to avoid paying custom duties on shore.

Hamilton further specified the locations where he wanted the ten cruisers to operate: two, for the coasts, bays and harbours of Massachusetts and New Hampshire; one, for the Sound between Long-Island and Connecticut; one, for

Hamilton further specified the locations where he wanted the ten cruisers to operate: two, for the coasts, bays and harbours of Massachusetts and New Hampshire; one, for the Sound between Long-Island and Connecticut; one, for

the Bay of New York; one, for the Bay of Delaware; two, for the Bay of Chesapeak; (these of course to ply along the neighboring coasts); one, for the coasts, bays and harbours of North Carolina; one, for the Coasts, bays and harbours of South Carolina; and one, for the Coasts, bays & harbours of Georgia.

Understanding full well the powers of patronage, Hamilton and Washington directed that the cutters be built in different ports around the country. Hamilton was sensitive to regional favoritism and advised Washington to build the cutters in “different parts of the Union.” As a result, the decentralized fleet lacked the uniformity of design taken for granted today. It is believed that the cutters variously displaced between 38 and 70 tons with a length between 36 to 40 feet. In certain cases, smaller schooners were re-rigged as sloops.

In an effort to promote domestic manufacturing consistent with his objectives that were later fleshed out in his Report on Manufacturing, Hamilton required all cutter materials to be produced domestically. Not known for a proclivity to delegate, Hamilton personally issued orders detailing the specific number of supplies, weapons (ten muskets and bayonets, twenty pistols), and tools (including two chisels and one broad ax) to be issued each cutter.

Hamilton opined that “[b]oats of from thirty six to forty feet keel, will answer the purpose, each having one Captain, one Lieutenant and six mariners, and armed with swivels. The first cost of one of these boats, completely equipped, may be computed at One thousand dollars.”

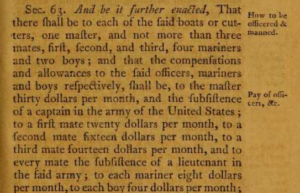

As envisioned by Hamilton, junior officers were necessary in case one or more had to ride on an inbound merchant vessel to secure the integrity of its cargo. Cutter officers were responsible for enlisting each cutter’s crew (consisting of the master, first, second and third mates, four enlisted men; and two cabin boys).

As an incentive and to supplement their base salary, officers and crew could participate in the proceeds of fines, penalties, and forfeitures on smuggled goods.

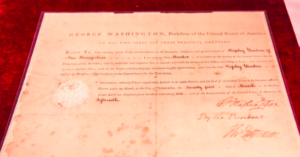

Pictured to the right is a commission dated March 21, 1791 appointing Hopley Yeaton as a Master in the Cutter service. The commission is signed by President Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. The original is held by the Library of Congress.

Pictured to the right is a commission dated March 21, 1791 appointing Hopley Yeaton as a Master in the Cutter service. The commission is signed by President Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. The original is held by the Library of Congress.

Additional reading:

Coast Guard Historian’s Office

Library of Congress – Coast Guard documents

Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (2004)

225th Anniversary of the Coast Guard and Its Treasury Department Origins