Cumberland Road, Internal Improvements & Clay’s “American System”

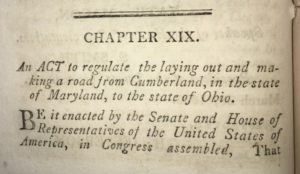

“An Act to regulate the laying out and making a road from Cumberland, in the state of Maryland, to the State of Ohio”

[9th Congress, First Session, Chapter 19] Click here for the text.

In March of 1806 Congress authorized the appointment of three commissioners to plot out a road to extend from Cumberland in western Maryland to the new state of Ohio. The Act further provided that construction would commence after the President approved the written report and survey for the project. The sum of $30,000 was appropriated for the President to draw upon to defray the expense of “laying out and making said road.”

The commissioners were required to be “discrete and interested citizens” who were subject to Senate confirmation. The Act specified that the commissioners were to be paid $4 per day and were authorized to employ one surveyor (at $3 per day), two chainmen (at $1 per day), and one marker (at $1 per day), “for whose faithfulness and accuracy” the commissioners would be responsible.

The commissioners were required to be “discrete and interested citizens” who were subject to Senate confirmation. The Act specified that the commissioners were to be paid $4 per day and were authorized to employ one surveyor (at $3 per day), two chainmen (at $1 per day), and one marker (at $1 per day), “for whose faithfulness and accuracy” the commissioners would be responsible.

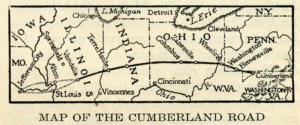

The Cumberland Road (also called the “National Road”) would become the first federal highway and “gateway to the West.” Construction began in 1811 and approximately twenty years later the Cumberland Road would extend from Maryland across Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana to Vandalia, Illinois, within reach of the Mississippi River. In many respects the Road became Main Street in many early settlements along its route, earning it the nickname “The Main Street of America.”

The Cumberland Road (also called the “National Road”) would become the first federal highway and “gateway to the West.” Construction began in 1811 and approximately twenty years later the Cumberland Road would extend from Maryland across Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana to Vandalia, Illinois, within reach of the Mississippi River. In many respects the Road became Main Street in many early settlements along its route, earning it the nickname “The Main Street of America.”

Background: In 1803, when Congress admitted Ohio in the Union as a state, it set aside 5% of the net proceeds from the sale of public lands for purposes of “laying out, opening and making roads.” By 1806, Congress was satisfied that sufficient funds had been accumulated to begin the surveying process. President Jefferson signed the Act into law.

Background: In 1803, when Congress admitted Ohio in the Union as a state, it set aside 5% of the net proceeds from the sale of public lands for purposes of “laying out, opening and making roads.” By 1806, Congress was satisfied that sufficient funds had been accumulated to begin the surveying process. President Jefferson signed the Act into law.

Cumberland had served as a military headquarters for Colonel George Washington during the French and Indian War. During the Whiskey Rebellion President Washington returned to Cumberland in 1794 to review his troops before marching to western Pennsylvania. Click here for a link to a discussion of the Whiskey Tax and Whiskey Rebellion.

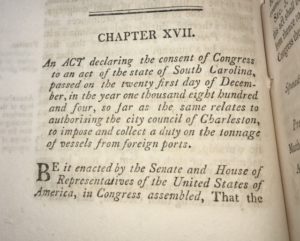

Internal Improvements: The Cumberland Road Act was not created in isolation. The Ninth Congress also adopted several related bills aimed at improving national infrastructure. For example, Congress authorized Philadelphia to collect a duty of 4 cents per ton on all ships departing the port. The revenue was dedicated to building piers and improving navigation on the Delaware River. See Chapter XII, Acts of the 9th Congress, 1st Session. Similarly, Congress authorized Charleston, South Carolina, to impose a levy on ships, not exceeding six cents per ton, from any foreign port. See Chapter XVII, Acts of the 9th Congress, 1st Session.

Other bills provided for the building of light houses in the Long Island Sound in New York and Rhode Island. See Chapter IV, Acts of the 9th Congress. Congress also directed the Secretary of the Treasury to survey the coast of North Carolina between Cape Hatteras and Cape Fear for purposes of erecting lighthouses. See Chapter XXIV, Acts of the 9th Congress. While not an infrastructure project per se, the Ninth Congress also approved appropriations for the Library of Congress. See Chapter VI, Acts of the 9th Congress.

Other bills provided for the building of light houses in the Long Island Sound in New York and Rhode Island. See Chapter IV, Acts of the 9th Congress. Congress also directed the Secretary of the Treasury to survey the coast of North Carolina between Cape Hatteras and Cape Fear for purposes of erecting lighthouses. See Chapter XXIV, Acts of the 9th Congress. While not an infrastructure project per se, the Ninth Congress also approved appropriations for the Library of Congress. See Chapter VI, Acts of the 9th Congress.

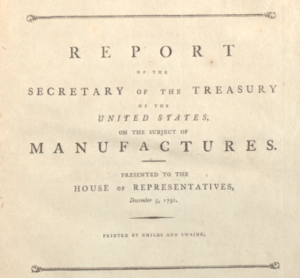

Hamilton’s 1791 Report on Manufactures and Gallatin’s 1808 Report on Roads and Canals: Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of Treasury, and Albert Gallatin, Jefferson’s Secretary of Treasury, both agreed on the importance of internal improvements. Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures contained an entire section devoted to the importance of the “facilitating of the transport of commodities.” Hamilton argued that “There can certainly be no object, more worthy of the cares of the local administrations; and it were to be wished, that there was no doubt of the power of the national Government to lend its direct aid, on a comprehensive plan. This is one of those improvements, which could be prosecuted with more efficacy by the whole, than by any part or parts of the Union.” Click here for the text of Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures. Click here to read about Hamilton’s Report on the Public Credit.

Hamilton’s 1791 Report on Manufactures and Gallatin’s 1808 Report on Roads and Canals: Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of Treasury, and Albert Gallatin, Jefferson’s Secretary of Treasury, both agreed on the importance of internal improvements. Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures contained an entire section devoted to the importance of the “facilitating of the transport of commodities.” Hamilton argued that “There can certainly be no object, more worthy of the cares of the local administrations; and it were to be wished, that there was no doubt of the power of the national Government to lend its direct aid, on a comprehensive plan. This is one of those improvements, which could be prosecuted with more efficacy by the whole, than by any part or parts of the Union.” Click here for the text of Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures. Click here to read about Hamilton’s Report on the Public Credit.

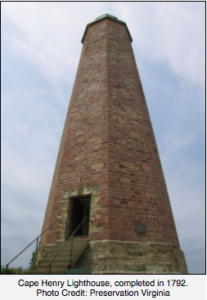

Constitutionality: While some, including Jefferson and Madison, were strong believers in state sovereignty, the very first Congress approved the Lighthouse Act of 1789 within months of taking office. Click here for the “Act for the Establishment and Support of Lighthouses, Beacons, Buoys, and Public Piers,” which was the 9th official Act of Congress and the first ever federal public works project. The Cape Henry lighthouse pictured above was the first lighthouse built under the Lighthouse Act of 1789, making it the first federal construction project under the new federal Constitution. When it opened 1792 it accomplished the Act’s mandate to open a lighthouse “near the entrance of the Chesapeake Bay.” Not surprisingly, Alexander Hamilton was actively involved in the construction project, investigating the site in Virginia, overseeing contracts and monitoring progress on construction.

The Postal Clause of the Constitution, Article I, Section 8, Clause 7, authorizes Congress “To establish Post Offices and Post Roads.” To the extent that the Cumberland Road would serve as a post road its construction was expressly authorized. Of course, the Commerce Clause in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3, authorizes Congress to “regulate Commerce” with foreign nations and “among the several States,” serving as as an implied power supporting infrastructure spending.

In Federalist 42, Madison wrote in favor of establishing post roads as a national responsibility. He argued that, “The power of establishing post roads, must, in every view, be a harmless power; and may, perhaps, by judicious management, become productive of great public conveniency. Nothing, which tends to facilitate the intercourse between the states, can be deemed unworthy of the public care.”

After the Louisiana Purchase and the prospect of land sales and federal surpluses, President Jefferson embraced internal improvement. In his final Annual Address to Congress in 1808 he advocated for appropriating surplus revenue “to the improvements of roads, canals, rivers, education, and other great foundations of prosperity and union under the powers which Congress may already possess or such amendment to the Constitution as may be approved by the States?” Click here for a link. Historian Henry Adams would later write that Jefferson (the Sage of Monticello) astutely “gave up his Virginia dogmas” and abandoned his traditionally pro-agriculture and anti-industrial views.

In the aftermath of the War of 1812, it became clear to many that manufacturing and internal improvement were increasingly important. Riding a wave of nationalism, Henry Clay declared that the country needed a new integrated program, which he dubbed the “American System.”

President Monroe agreed that infrastructure was necessary, but thought that federal authority to build or operate internal improvements was limited. He proposed that Congress should introduce a constitutional amendment clarifying this power. Congress never acted, however, because many believed that the federal government already had the requisite authority for national infrastructure spending.

In 1822, Monroe vetoed a bill to repair the Cumberland Road. Nevertheless, after studying the issue, including discussing the matter with Supreme Court justices, Monroe changed his mind. In 1824, he agree to allocate funding for additional surveys. In 1825, he signed a bill into law to extended the Cumberland Road from Wheeling to Zanesville, Ohio.

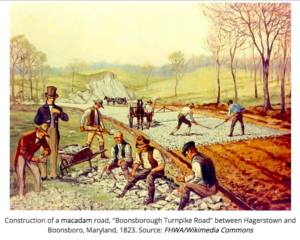

Post script: In its heyday, Cumberland was the second largest city in the state of Maryland, serving as the staging area for thousands of Americans to begin their westward migration on the Cumberland Road through the Appalachian mountains. The Cumberland Road applied the latest paving techniques developed in England by the Scottish engineer, John McAdam. The revolutionary construction process known as mcadamization employed a slightly raised, convex surface, which road allowed water to drain, rather than penetrate the foundation, made of gravel on a base of larger symmetrical stones.

Post script: In its heyday, Cumberland was the second largest city in the state of Maryland, serving as the staging area for thousands of Americans to begin their westward migration on the Cumberland Road through the Appalachian mountains. The Cumberland Road applied the latest paving techniques developed in England by the Scottish engineer, John McAdam. The revolutionary construction process known as mcadamization employed a slightly raised, convex surface, which road allowed water to drain, rather than penetrate the foundation, made of gravel on a base of larger symmetrical stones.

In 1818 the Cumberland Road extended to Ohio River at Wheeling, Virginia (now in West Virginia). In March of 1825, Congress appropriated funding to extend the Road from Wheeling to Zanesville, Ohio. President John Quincy Adams eventually transferred responsibility to the War Department and the Army Corp of Engineers. Beginning in 1833 Congress decided that portions of the road would become the financial responsibility of individual states, which could charge tolls to maintain the road.

In 1818 the Cumberland Road extended to Ohio River at Wheeling, Virginia (now in West Virginia). In March of 1825, Congress appropriated funding to extend the Road from Wheeling to Zanesville, Ohio. President John Quincy Adams eventually transferred responsibility to the War Department and the Army Corp of Engineers. Beginning in 1833 Congress decided that portions of the road would become the financial responsibility of individual states, which could charge tolls to maintain the road.

Following the Financial Panic of 1837 Congress declined to provide additional funding to continue construction beyond Vandalia, Illinois, which was the territorial capital of the Illinois Territory. Even Henry Clay, who had been a great proponent of internal improvements, understood that railroads and canals had eclipsed the importance of the once mighty Cumberland Road. For example, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) was chartered in 1827 to connect Baltimore with the Ohio River. Nevertheless, the Cumberland Road had established the precedent of successful federal funding of a national infrastructure project. Today the Cumberland Road forms part of U.S. Route 40. Interestingly, the Cumberland Road does not pass through the famous Cumberland Gap mountain pass, which is south of the Cumberland Road, along the Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee border.

Additional reading:

Alexander Hamilton Appreciation Society

Alexander Hamilton’s Manufacturing Message, Bruce Katz & Jessica Lee (CNN)

Thanks to my father who told me about this weblog, this weblog is truly amazing.

Edwin,

Thanks for the complement. Your site is also very impressive.

If you ever get a chance to come to South Florida, you might enjoy the Dezer Car Collection:

http://www.dezercollection.com

Best regards,

Adam

Nice to have a detective following the leads with us…