An Act to Encourage Vaccination and Early Public Health Laws

The struggle to protect public health from infectious disease predates the establishment of the United States. Congress first recognized the need for federal legislation to promote vaccination in 1813. The Act to Encourage Vaccination was signed into law by President Madision, only a decade after Edward Jenner’s discovery of a smallpox vaccine in 1796.

The need to quarantine those infected with disease, including sailors, had been understood for centuries. While the founding generation did not understand the mechanism for how disease was spread, they welcomed a federal role in protecting public health.

This two-part post tells the story of early federal efforts to fight disease. A prior post, Part I, discusses early American quarantine laws, including the 1796 Act Relative to Quarantine signed into law by President Adams following the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793. Part II continues the discussion of vaccination and public health in early American history.

The 1813 Act to Encourage Vaccination discussed below was the first federal health care law of its kind. While Congress had previously provided health care for sick sailors beginning in 1798, the 1813 Act to Encourage Vaccination was the first federal health care law that applied nationally to the general public, rather than a specific segment of the workforce. Click here for a discussion of the Act for the Relief of Sick & Disabled Seamen, 1 Stat. 605-06 (1798). The 1798 Act created the U.S. Marine Hospital Service, which ultimately evolved into the national U.S. Public Health Service.

Signed into law by President Madison, the 1813 Act to Encourage Vaccination established a national vaccination program. The concept of promoting vaccination had been warmly embraced by President Jefferson. Jefferson inoculated over 200 members of his family, slaves and neighbors in 1801.

Public health and the founders

During the colonial period, Benjamin Franklin supported early methods of inoculation, having lost his four-year-old son, Francis Folger Franklin, to smallpox in 1736. Franklin helped establish the country’s first public hospital and the nation’s first American medical school.

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress created a Hospital Department for the Continental Army. John Adams lamented the fact that more soldiers died of smallpox than British bullets. The frugal New Englander wrote to his wife, Abigail, that, “The expense will be great, but humanity overcame avarice.”

Fearing the spread of smallpox during the Revolutionary War, General Washington ordered the inoculation of all American troops in 1777. For several months, 40,000 troops were inoculated and quarantined en masse. Strict secrecy was maintained to prevent the British from discovering the inoculation program, lest they launch a surprise attack upon the recovering American troops. Washington’s order was the first mass inoculation in military history. The difficult decision proved pivotal in ensuring the American victory during the Revolutionary War.

The new country’s foremost nationalist and proponent of federal power, Alexander Hamilton, described the need for governmental flexibility to address “national emergencies” in Federalist 23:

BECAUSE IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO FORESEE OR DEFINE THE EXTENT AND VARIETY OF NATIONAL EXIGENCIES, OR THE CORRESPONDENT EXTENT AND VARIETY OF THE MEANS WHICH MAY BE NECESSARY TO SATISFY THEM. The circumstances that endanger the safety of nations are infinite, and for this reason no constitutional shackles can wisely be imposed on the power to which the care of it is committed. Click here for a link to Federalist 23.

The 1813 Act to Encourage Vaccination

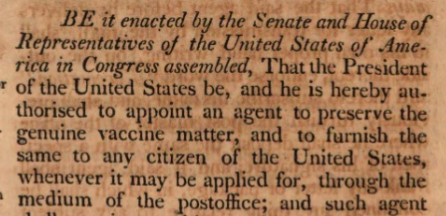

Congress adopted the Act to Encourage Vaccination during the War of 1812. The 1813 Vaccine Act [ch. 3, 2 Stat. 806 (1813)] was the first federal health program aimed at the general public. It has also been described as the first federal law dealing with consumer protection or pharmaceuticals. The 1813 Act was also the first instance where the federal government endorsed a particular medical practice. The Act is also significant as an early example of the federal government’s involvement with the American economy to promote the “General Welfare.”

The short, two section act authorized the President to appoint an agent to “preserve genuine vaccine matter, and to furnish the same to any citizen of the United States, whenever it may be applied for, through the medium of the post-office.” The Act subsidizes the shipment of vaccine around the country through the Post Office. Section 2 of the Act directed that “all letters or packages not exceeding half an ounce in weight, containing vaccine matter, or relating to the subject of vaccination, and that alone, shall be carried by the United States’ mail free of any postage, either to or from the agent who may be appointed to carry the provisions of this act into effect.”

It was hoped that the 1813 Act would establish a national source to make available and “preserve” reliable, uncontaminated and “genuine” smallpox vaccine. The Act was passed at the urging of Baltimore physician, Dr. James Smith who was promptly appointed the first National Vaccine Agent. The pioneering work of Dr. Smith and the establishment of the first public health program under the 1813 Act laid the groundwork for the Centers for Disease Control and the Food and Drug Administration.

The Act was repealed nine years later in the wake of a fatal accident and public scandal. Click here for a link to the Act to Repeal the Act to Encourage Vaccination, ch. 50, 3 Stat. 677 (1822).

Edward Jenner and the smallpox vaccine

One of the most feared diseases of its day, smallpox was a highly contagious virus that killed one third of those infected during deadly epidemics that reoccurred every few decades. British doctor Edward Jenner, the “father of immunology”, correctly theorized that protection against smallpox could be achieved through inoculation with cowpox, a related but much milder virus. Jenner would then prove that those vaccinated with cowpox were in fact immune to smallpox. This revolutionary discovery has saved countless lives.

In 1796, Jenner inserted pus from a milkmaid with cowpox into the arms of a healthy 8-year-old boy. Jenner proceeded to “variolate” the child and prove that a person could be successfully protected from smallpox, without having to be directly exposed to it. Jenner thus discovered the world’s first modern “vaccine”, a term coined by Jenner himself.

Prior to Jenner, doctors used a more primitive and dangerous method of inoculation (also called “variolation”) which involved taking pus or powdered scabs from patients with a mild case of smallpox and inserting the smallpox virus into the skin or nose of healthy individuals. Unlike a variolated patient who was exposed to smallpox, a vaccinated patient could not spread smallpox to others. Additionally, Jenner’s smallpox vaccine was comparatively safe and provided lifelong immunity. In contrast to vaccination, variation was a tedious process that would leave a patient sick for weeks and could trigger unintended smallpox outbreaks.

Thanks to Jenner’s discovery, smallpox has been completely eradicated. The smallpox vaccine is now obsolete precisely because of its effectiveness. The “germ theory” of disease was scientifically proven by Louis Pasteur in the 1860s. Jenner and Pasteur’s legacy continues today with the fourteen other diseases that American children are vaccinated against, including measles, mumps, rubella, tetanus and polio.

Vaccination in America

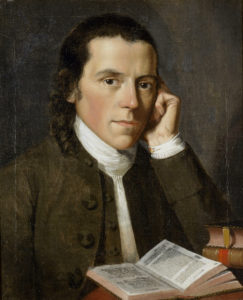

Jenner published his findings in 1798. Two years later, Harvard Professor Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse introduced smallpox vaccination to America. Waterhouse presented Jenner’s promising discovery to both President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson. In a letter dated December 25, 1800, Jefferson replied to Waterhouse that “every friend of humanity must look with pleasure on this discovery, by which one evil more is withdrawn from the condition of man…” A young Dr. Waterhouse is pictured below.

Jefferson was a leading proponent of inoculation. In a letter to Dr. Joseph Cox, another leading physican and medical professor of the day, Jefferson expressed him opinion that inoculation should be made available to the public at large:

I think it is important … to bring the practice of the [smallpox] inoculation to the level of common capacities, for to give to this discovery the whole of value, we should enable the great mass of the people to practice it on their own families & without an expense, which they cannot meet. Click here for a link to Jefferson’s April 30, 1802 letter to Dr. Coxe.

In his 1805 State of the Union, President Jefferson explained that “although the health laws of the States should be found to need no present revisal by Congress, yet commerce claims that [Congress’] attention be ever awake to them.” Thomas Jefferson, Fifth Annual Message to Congress (Dec. 3, 1805). Eight years later, Madison seized the initiative during the War of 1812 and made vaccination available with the 1813 Act.

Earlier efforts at Variolation

Prior to Dr. Jenner’s discovery of the cowpox vaccine to fight smallpox, variation was used intermittently to fight periodic epidemics. The Reverend Cotton Mather, an outspoken Massachusetts leader and scientist, was the first proponent of inoculation in the colonies. He convinced a local physician, Dr Zabdiel Boylston, to use variolation to fight smallpox. Mather had first learned of the medical practice in 1806 from African slaves. Mather also studied articles in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London promoting inoculation.

While controversial, variolation proved successful during a Boston epidemic in the early 1700s. Only 6 deaths were reported among 244 inoculated individuals (a mortality rate of only 2.5%), compared with 844 deaths among 5980 people (a mortality rate of 14%). This success led to wider adoption in the colonies, especially in Philadelphia. The procedure was still highly controversial. In 1721 Mather’s house was firebombed amid allegations that his efforts at inoculation were challenging God’s will.

Massachusetts Vaccination Law of 1810

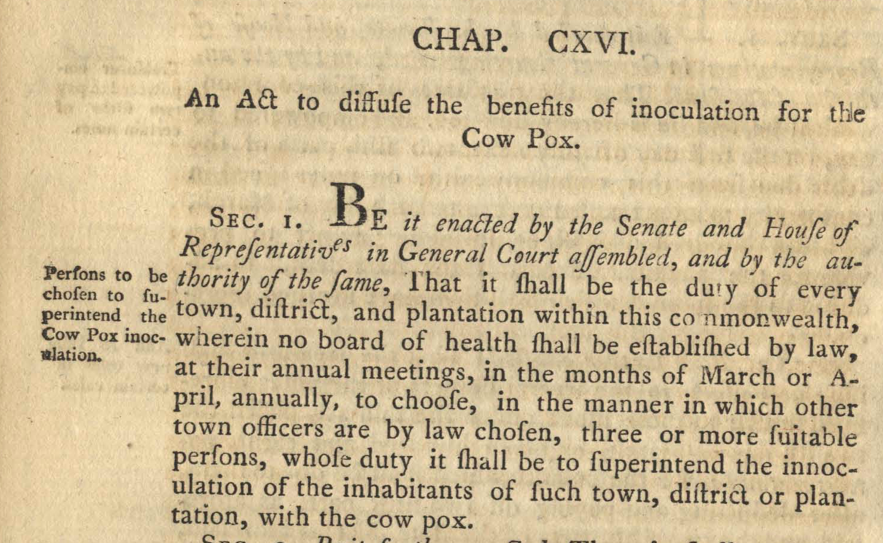

Massachusetts, an early leader in the development of public health, enacted the country’s first mandatory vaccination law in 1810. Click here for a link to the Massachusetts Act to Diffuse the Benefits of Inoculation for the Cow Pox, adopted March 6, 1810, which is pictured below.

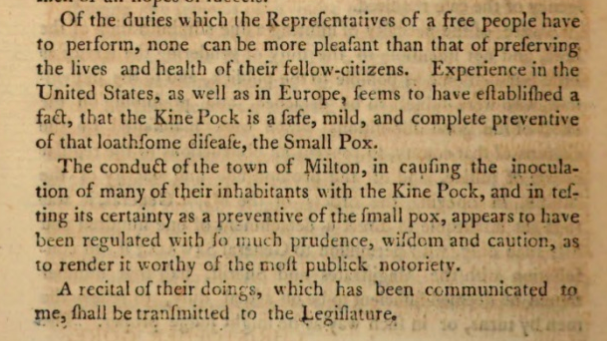

In a speech to the Massachusetts Assembly in January of 1810, Governor Christopher Gore cited the success by the Town of Milton Massachusetts which was an early adopter of Jenner’s vaccine. As described by the Governor, the vaccine was “a safe, mild and complete preventative of that loathsome disease, the Small Pox.” Click here for link to Governor Gore’s 1/25/1810 address to the Massachusetts Assembly. In 1827, Boston became the first city to require vaccination against smallpox for public school students.

Copied below is Governor Gore’s 1810 Address to the Massachusetts Assembly and the 1810 Act to Diffuse the Benefits of Inoculation for the Cow Pox.

Jacobson v. Massachusetts case:

In the 1905 case of Jacobson v Massachusetts, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the government’s right to require compulsory vaccination during a smallpox epidemic.

A Lutheran minister from Cambridge challenged a Massachusetts vaccination law authorizing the Board of Health to require vaccinations. In a seven to two ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court held that compulsory vaccination was a legitimate exercise of state “police powers” to guard public health, welfare, safety. The Court reasoned that vaccination of all citizens was not unreasonable if duly elected legislatures had determined that smallpox was a threat and that vaccination was an effective way to prevent. “Society based on the rule that each one is a law unto himself would soon be confronted with disorder and anarchy.”

Jacobson had argued that “a compulsory vaccination law is unreasonable, arbitrary and oppressive, and, therefore, hostile to the inherent right of every freeman to care for his own body and health in such way as to him seems best; and that the execution of such a law against one who objects to vaccination, no matter for what reason, is nothing short of an assault upon his person.” The Court disagreed holding that “the liberty secured by the Constitution of the United States to every person within its jurisdiction does not import an absolute right in each person, to be, at all times and in all circumstances wholly free from restraint.” Nevertheless, the Court acknowledged that there were limits to the state’s power to protect the public health and set forth the following reasonability test for public health laws:

I]t might be that an acknowledged power of a local community to protect itself against an epidemic threatening the safety of all, might be exercised in particular circumstances and in reference to particular persons in such an arbitrary, unreasonable manner, or might go so far beyond what was reasonably required for the safety of the public, as to authorize or compel the courts to interfere for the protection of such persons

Less than twenty years later, in 1922, the Supreme Court upheld mandatory vaccination requirements for public school attendance. Zucht v. King, 260 U.S. 174, 43 S.Ct. 24 (1922). In Zucht, the Court held that a school district could constitutionally exclude unvaccinated students from attending Texas schools. The Court observed that in the Jacobson case had determined that the law was “settled that it is within the police power of a state to provide for compulsory vaccination”.

Click here for a link to Part I, which discusses quarantine laws and Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793.

References:

History of Smallpox: Timelines (The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia: Inoculation (Monticello.org)