An Act Relative to Quarantine

The first federal quarantine law

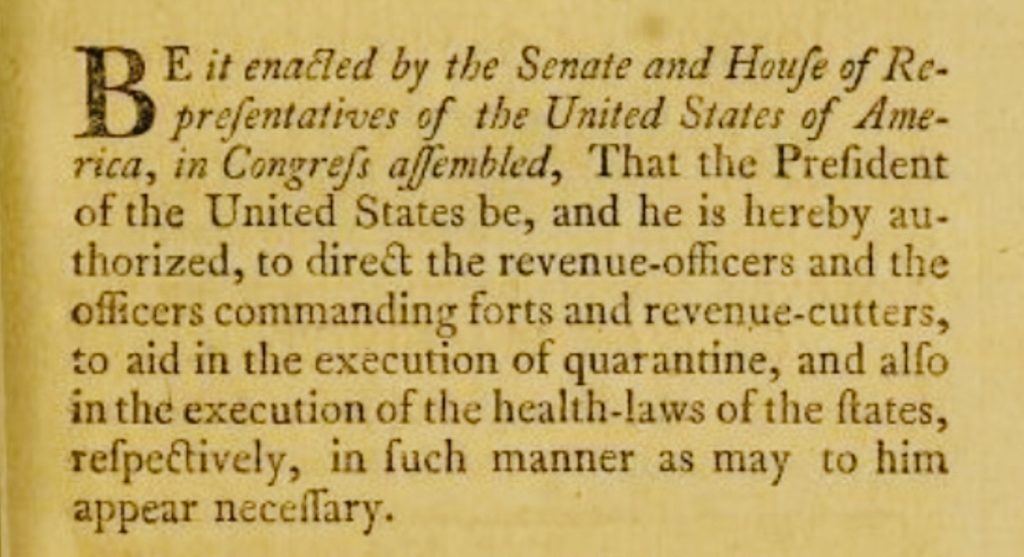

In May of 1796, Congress adopted the first federal quarantine law in response to a series of deadly yellow fever epidemics. The law, entitled “An Act Relative to Quarantine”, 1 Stat. 474, was adopted by the Third Congress and signed by George Washington without much controversy. The remarkably simple law consisted of a single paragraph which provided as follows:

. . . That the President of the United States be, and he is hereby authorized, to direct the revenue-officers and the officers commanding forts and revenue-cutters, to aid in the execution of quarantine and also in also in the execution of the health-laws of the states, respectively, in such manner as may to him appear necessary. Click here for a link to the Act Relative to Quarantine, which is pictured below:

The Act authorized President Washington to aid the states, in his discretion, “in the execution of quarantine” and in the execution of state “health-laws”. At the time the federal government was less than a decade old. The resources available for President Washington to deploy, “as may to him appear necessary,” were identified as revenue officers under the Treasury Department and military officials in the War Department. The primary responsibility for enforcing quarantines would nonetheless fall to the individual states.

Earlier, in 1794, Congress had authorized Maryland to impose duties on ships arriving in Baltimore from foreign ports to pay for a health officer in the Port of Baltimore. Permission from Congress for a state to impose taxes on ships was required by Art. I, Sec. 10, cl. 2 of the Constitution which provides that: No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it’s inspection Laws.

Three years later, a second and more comprehensive federal quarantine law was adopted in February of 1799 by the Fifth Congress. The “Act Respecting Quarantines and Health Laws”, 1 Stat. 619, repealed the 1796 Act (which was only a single paragraph) and replaced it with a more elaborate eight section bill described below. Click here for a link to the 1799 Act Respecting Quarantines and Health Laws.

The 1799 Act retained the model of federal agencies providing assistance to state authorities to enforce “quarantines and other restraints” adopted by the states. The Act authorized federal officials to aid in the execution of state “quarantine and health laws” as directed by the Secretary of the Treasury.

The Act also provides a mechanism for evacuation of federal employees from the scene of an epidemic. In the case of “prevalence of any contagious or epidemic disease,” the Secretary of the Treasury was empowered to order the removal of revenue officers, with the courts authorized to relocate and provide for the removal of prisoners. In the event that the an epidemic struck the seat of government, the President was given the discretion to direct the removal of public offices.

The 1799 Act was signed by President Adams, who understood the danger posed by Yellow Fever and other infectious diseases. Adams had been inoculated against smallpox years earlier by Dr. Joseph Warren (the hero of the Battle of Bunker Hill). Among those who contracted the feared disease were Abigail Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and Dr. Benjamin Rush (who heroically tried to treat patients in Philadelphia). Those who did not survive included Dolly Madison’s first husband, and Philadelphia newspaper publishers Benjamin Franklin Bache (Benjamin Franklin’s grandson) and John Fenno.

Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793

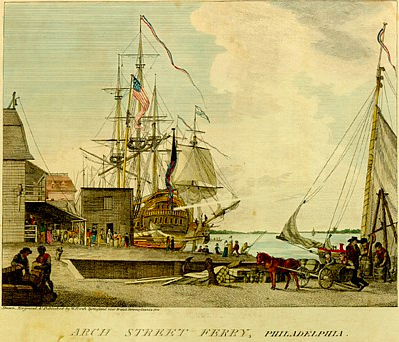

During the 1790s, repeated Yellow Fever epidemics struck the nation’s largest city, Philadelphia. The outbreaks were so severe that the federal government temporarily relocated away from Philadelphia, the federal government’s provisional capital, to escape the devastating epidemic.

The 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever epidemic was one of the worst in American history. Ultimately, the disease would claim 5,000 lives between August and November of 1793, forcing 20,000 to flee the crowded city of 50,000. It is believed that the disease was spread by French refugees from Saint-Domingue. The 2,000 immigrants were fleeing a slave rebellion that would give birth to the new nation of Haiti.

The 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic is believed to begun along the Arch Street Wharf in Philadelphia, where the first cluster of cases were identified.

The 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic was described by Washington as a “calamitous situation in Philadelphia” which left the city “almost depopulated by removals & deaths.” Click here for a link to Washington’s October 14, 1793 letter to James Madison. In a letter to Hamilton describing the “calamity which has befallen Philadelphia”, Washington sought guidance on whether Congress could convene at another, safer location. Click here for Washington’s October 14, 1793 letter to Hamilton.

Thomas Jefferson, a strict constructionist, was of the view that the President could not unilaterally relocate Congress. Disagreeing with Jefferson, Hamilton wrote to Washington that under extraordinary circumstances the President had the discretion to set the time and place for the convening of Congress. Mindful that there were “respectable opinions against the power of the President to change the place of meeting,” Hamilton suggested that it was expedient for the President to recommend a location for Congress to reconvene.

Ultimately, Washington and Hamilton concurred that Congress should meet in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Other locations that were considered were Trenton, Reading, Lancaster, and Wilmington. Click here for a link to Hamilton’s October 24, 1793 letter to Washington. As a result, in November of 1793 Washington, his cabinet and Congress relocated to Germantown, until the Philadelphia epidemic ran its course. While it was not known at the time, Yellow Fever was primarily spread by mosquitos, which explains why seasonal epidemics ceased when winter arrived.

Congress acted the following year to explicitly authorize the President to respond to national emergencies. In April of 1794, Congress adopted an “Act to Authorize the President, in certain cases, to alter the Place of holding a session of Congress.” Click here for a link to the 1794 Act Authorizing the President to Alter the Place for Holding a Session of Congress.

The Act provided the President with the authority to convene Congress at an alternate location that he may judge proper “whenever in the opinion of the President a contagious illness “or the existence of other circumstances” would be “hazardous to the lives or health”.

History of quarantine

The practice of isolating disease dates back to antiquity. The book of Leviticus contains a discussion of the treatment and procedure to quarantine lepers. In the 7th century, Roman Emperor Justinian required all new arrivals from plague-infested areas be temporary isolated. In imperial China sailors and foreigners were also subject to quarantine.

Venice established the first regularized system of quarantine to combat bubonic plague (also known as the Black Death). The Venetians detained ships for 40 days (the word quarantine is derived from the Italian quaranta giorni, for “forty days”). The world’s first maritime quarantine station, or “lazaretto” (named for Saint Lazarus) was built on an island near Venice in 1403.

Quarantine laws were first adopted in colonial America in the 1600s. In 1647, Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the first sea-based quarantine in the American colonies. The regulation quarantined ships from Barbados in an effort to limit the plague from spreading.

Two decades later, in 1662, the Town of East Hampton, Long Island, instituted the first land-based quarantine to contain the spread of smallpox. The Town Records for March 2, 1662 provided that:

“…no Indian shall come to towne into the street after sufficient notice upon penalty of 5s. or be whipped until they be free of the smallpoxe… and if any English or Indian servant shall go to their wigwams they shall suffer the same punishment.”

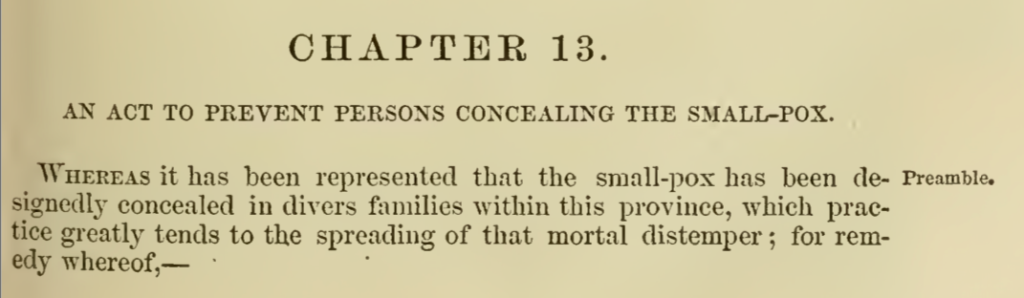

New York City followed suit in 1663 with additional quarantine restrictions to resist the spread of smallpox. Copied below is the Massachusetts Act to Prevent Persons Concealing the Small-Pox, adopted 1732. Among other things, the Massachusetts Act required the placement of a six foot pole with a red cloth in front of an infected house to warn the public. In the 1730s, New York City built a formal quarantine station on Bedlow’s Island in New York Harbor. Years later, after it was torn down, the island became the site of the Statue of Liberty.

Following Philadelphia’s 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic, Congress adopted An Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Seamen. Click here for a discussion of the Act, which created the nation’s first payroll tax to provide health care and hospital care for merchant seaman.

The first quarantine hospital in America was built in Philadelphia in 1799. The 10-acre “Lazaretto”, which included a hospital, offices and residences, was located on the banks of the Delaware River. It processed ships, cargo and passengers through the port of Philadelphia for nearly a century.

Similarly, in New York patients were quarantined at Riverside Hospital on Brother Island in New York’s East River between 1885 to 1938. The most famous patient quarantined there was “Typhoid Mary”. Similar facilities were used in other major port cities, including Angel Island off San Francisco and Boston’s pest house.

A pending post will discuss the history of immunization laws and Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine.

Additional reading:

History of Quarantine (Centers for Disease Control)

A Brief History of Quarantines in the United States (Washington Post)