This post is a continuation of a discussion of the framers, the Constitution, and the impeachment trial of President Donald J. Trump. Both the House Managers arguing for impeachment and the lawyers defending the President agree that intent of the founders is relevant in the Senate trial.

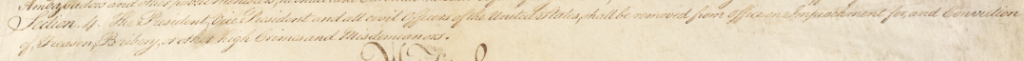

The phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” is not defined in Section 4 of Article II of the Constitution. Accordingly, the arguments and legal briefs cite to the notes of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, the state ratification debates in 1788, and The Federalist Papers. In particular, Federalist No. 65 is repeatedly mentioned in the briefs, the House Managers’ opening statements, and the Q & A’s before the Senate.

Part I of this post provides an overview and discusses the House Managers’ Trial Brief. This post (Part II), discusses the President’s Trial Brief and legal arguments. As discussed in Part I, the House Managers argue, among other things, that when drafting the Constitution, the founders intended “abuse of power” to be impeachable. By contrast, the President’s lawyers argue that the impeachment articles brought against President Trump are “structurally deficient and can only result in acquittal.”

While the House Managers emphasize Federalist No. 65 and the broad and flexible meaning of the phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors,” the President’s lawyers focus on the “real danger” of partisan impeachments recognized by Hamilton in Federalist No. 65. The President’s brief also cites to Jefferson’s concern that impeachment is “the most formidable weapon for the purposes of dominant faction that ever was contrived.”

Both sets of briefs ground their arguments in the drafting history of the phrase high Crimes and Misdemeanors. The President’s brief places particular emphasis on Gouverneur Morris’ position that “few” offenses “ought to be impeachable,” and the “cases ought to be enumerated and defined.” When the term “maladministration” was proposed as a ground for impeachment it was rejected based on Madison’s concern that “[s]o vague a term” would be equivalent to a tenure during the “pleasure of the Senate.” Citing William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, the President argues that the framers restricted impeachment to specified offenses of “already known and established law,” not amorphous abuses of power.

Click here for a link to the Constitution in the National Archives. A copy of the impeachment clause in Article II, Section 2 is copied below.

President Trump’s Trial Brief

Among the authorities cited in the President’s Trial Brief are Alexander Hamilton (cited 24 times); James Madison (cited 20 times); Gouverneur Morris (cited 6 times), James Iredell (cited 5 times); George Mason (cited 2 times); Charles Pinckney (cited once) and a letter from Thomas Jefferson to James Madison in 1798. The House Managers’ Trial brief cites to three of The Federalist essays (Nos. 65, 69, and 69). The President’s Trial Brief cites to Federalist No. 48, 49, 51, 65, and 66.

Click here for a link to the President’s Trial Brief, which contains an entire background section describing the “Text and Drafting History of the Impeachment Clause.”

Copied below are selections from the President’s Trial Brief:

- The Framers foresaw that the House might at times fall prey to tempestuous partisan tempers. Alexander Hamilton recognized that “the persecution of an intemperate or designing majority in the House of Representatives” was a real danger in impeachments, and Jefferson acknowledged that impeachment provided “the most formidable weapon for the purposes of dominant faction that ever was contrived.” That is why the Framers entrusted the trial of impeachments to the Senate. The Federalist 65 (Alexander Hamilton); Letter from Thomas Jefferson to James Madison (Feb. 15, 1798).

- As Justice Story explained, the Framers saw the Senate as a tribunal “removed from popular power and passions . . . and from the more dangerous influence of mere party spirit,” and guided by “a deep responsibility to future times.” Now, perhaps as never before, it is essential for the Senate to fulfill the role Hamilton envisioned for it as a “guard[] against the danger of persecution, from the prevalency of a factious spirit” in the House. The Federalist 66 (Alexander Hamilton).

- On each of the two prior occasions that the House adopted articles of impeachment against a President, the Senate refused to convict on them. Indeed, the Framers wisely forewarned that the House could impeach for the wrong reasons. That is why the Constitution entrusts the Senate with the “sole Power to try all Impeachments.” The Federalist 65 (Alexander Hamilton); U.S. Const. art. I, § 3, cl. 6.

- House Democrats’ claim that the Senate can remove a President from office for running afoul of some ill-defined conception of “abuse of power” finds no support in the text or history of the Impeachment Clause. As explained above, by limiting impeachment to cases of “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors,” the Framers restricted impeachment to specific offenses against “already known and established law.” That was a deliberate choice designed to constrain the power of impeachment. Restricting impeachment to offenses established by law provided a crucial protection for the independence of the Executive from what James Madison called the “impetuous vortex” of legislative power. The Federalist 48 (James Madison).

- As many constitutional scholars have recognized, “the Framers were far more concerned with protecting the presidency from the encroachments of Congress . . . than they were with the potential abuse of executive power.” The impeachment power necessarily implicated that concern. If the power were too expansive, the Framers feared that the Legislative Branch may “hold [impeachments] as a rod over the Executive and by that means effectually destroy his independence.” 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 at 66 (Max Farrand ed., 1911) (Charles Pinckney).

- One key voice at the Constitutional Convention, Gouverneur Morris, warned that, as they crafted a mechanism to make the President “amenable to Justice,” the Framers “should take care to provide some mode that will not make him dependent on the Legislature.” To limit the impeachment power, Morris argued that only “few” “offences . . . ought to be impeachable,” and the “cases ought to be enumerated & defined.” 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 at 65 and 69.

- Indeed, the debates over the text of the Impeachment Clause particularly reveal the Framers’ concern that ill-defined standards could give free rein to Congress to utilize impeachment to undermine the Executive. As explained above, when “maladministration” was proposed as a ground for impeachment, it was rejected based on Madison’s concern that “[s]o vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during [the] pleasure of the Senate.” 2 Records of the Federal Convention at 550.

- Madison rightly feared that a nebulous standard could allow Congress to use impeachment against a President based merely on policy differences, making it function like a parliamentary no-confidence vote. That would cripple the independent Executive the Framers had crafted and recreate the Parliamentary system they had expressly rejected. Circumscribing the impeachment power to reach only existing, defined offenses guarded against such misuse of the authority.

- Alexander Hamilton’s description in Federalist No. 65 does not support House Democrats’ theory of a vague abuse-of-power offense. In an often-cited passage, Hamilton observed that the subjects of impeachment are “offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust.” The Federalist 65. Hamilton was merely noting fundamental characteristics common to impeachable offenses—that they involve (or “proceed from”) misconduct in public office or abuse of public trust. He was no more saying that “abuse or violation of some public trust” provided, in itself, the definition of a chargeable offense than he was saying that “misconduct of public men” provided such a definition.

- As Luther Martin, who had been a delegate at the Constitutional Convention, summarized the point at the impeachment trial of Justice Samuel Chase in 1804, “[a]dmit that the House of Representatives have a right to impeach for acts which are not contrary to law, and that thereon the Senate may convict and the officer be removed, you leave your judges and all your other officers at the mercy of the prevailing party.” The Framers prevented that dangerous result by limiting impeachment to defined offenses under the law.

- There is no reason to think that the Framers designed a mechanism for the profoundly disruptive act of impeaching the President that could be accomplished through any unfair and arbitrary means that the House might invent. Impeachment is not just a political process unconstrained by law. “The subjects of [an impeachment trial] are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust”—that is, “POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.” The Federalist 65.

- But “Hamilton didn’t say the process of impeachment is entirely political. He said the offense has to be political.” Alan M. Dershowitz, Hamilton Wouldn’t Impeach Trump, Wall St. J. (Oct. 9, 2019). “Hamilton’s description in Federalist 65 should not be taken to mean that impeachments have a conventional political nature, unmoored from traditional criminal process.” J. Richard Broughton, Conviction, Nullification, and the Limits of Impeachment As Politics, 68 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 275, 288 (2017).

- Hamilton emphasized that impeachment and removal of “the accused” must be based on partially legal considerations involving “real demonstrations of innocence or guilt” rather than purely political factors like “the comparative strength of parties.” The Federalist 65.

- It would be incompatible with the Framers’ understanding of the “delicacy and magnitude of a trust which so deeply concerns the political reputation and existence of every man engaged in the administration of public affairs” to think that they envisioned a system in which the House was free to devise any arbitrary or unfair mechanism it wished for impeaching individuals. The Federalist 65.

- The Framers intended the impeachment power to be limited to “guard[] against the danger of persecution, from the prevalency of a factious spirit.” The Federalist 66.

- The Framers foresaw clearly the possibility of such an improper, partisan use of impeachment. As Hamilton recognized, impeachment could be a powerful tool in the hands of determined “pre-existing factions.” The Federalist 65.

- The Framers fully recognized that “the persecution of an intemperate or designing majority in the House of Representatives” was a real danger. That is why they chose the Senate as the tribunal for trying impeachments. Further removed from the politics of the day than the House, they believed the Senate could mitigate the “danger that the decision” to remove a President would be based on the “comparative strength of parties” rather “than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.” The Federalist 65.

- The Senate would thus “guard[] against the danger of persecution, from the prevalency of a factious spirit” in the House. The Federalist 66 (Alexander Hamilton). It now falls to the Senate to fulfill the role of guardian that the Framers envisioned and to reject these wholly insubstantial Articles of Impeachment that have been propelled forward by nothing other than partisan enmity toward the President.

- These Articles reflect nothing more than the “persecution of an intemperate or designing majority in the House of Representatives” that the Framers warned against. The Federalist 65.