The Founders and the Impeachment Trial of President Donald J. Trump

Part I – Overview and House Trial Brief

The framers of the Constitution figure prominently in the impeachment trial of President Donald J. Trump. Given the limited number of precedents for presidential impeachment in American history, the intent of the founders is certainly relevant to both the prosecution and defense. The phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” is not defined in Section 4 of Article II of the Constitution. It is thus only natural to look to the notes of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, along with the state ratification debates, and The Federalist Papers, which are widely regarded as providing the best evidence of the founding father’s intent.

This post will discuss the multiple references to the founding fathers in the trial briefs submitted to the Senate. This post will also discuss the controversy over a particular letter Hamilton wrote to George Washington in 1792, which has been repeatedly invoked during the trial along with Federalist No. 65.

Overview of Senate Trial Briefs

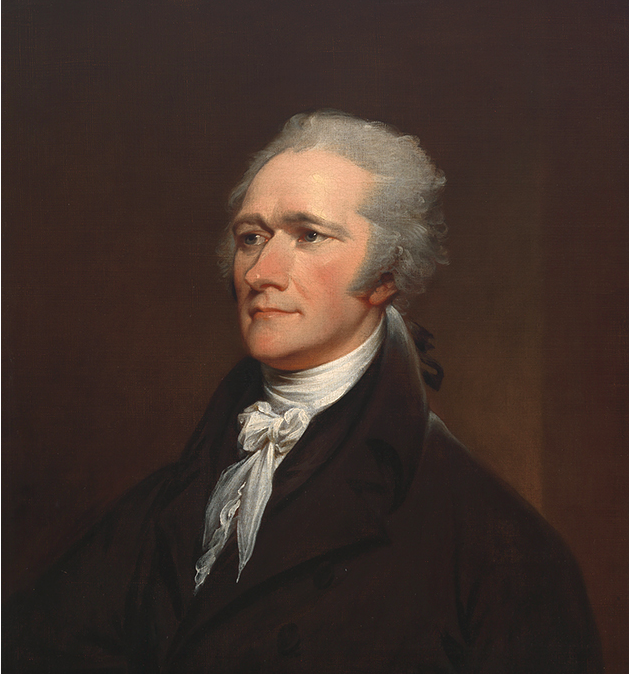

At least ten members of the founding generation are cited in trial briefs submitted by the House Managers and the President’s lawyers. Not surprisingly, citations to Alexander Hamilton and James Madison outpace the other founders, as they were principle drafters of The Federalist Papers. Moreover, James Madison, George Mason and Gouverneur Morris are cited for their central roles in the drafting of the phrase, “Treason, Bribery and other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

The House Managers’ Trial Brief cites to Alexander Hamilton nine times. The President’s Trial Brief cites to Hamilton twenty-four times. Even though Hamilton did not draft the impeachment clause, there is bi-partisan agreement that Hamilton’s opinions bear on this subject. Some might find it surprising that Hamilton was cited more times by the President’s team than by the House Democrats. With that said, the President’s legal brief is substantially longer (109 pages excluding appendices) compared to the House Brief (61 pages).

In addition to multiple citations to Hamilton (cited a combined total of 33 times), Madison (cited 21 times) and The Federalist Papers, eight additional founders make appearances in the trial briefs, including: George Mason, Gouverneur Morris, Edmond Randolph, James Iredell, George Washington, Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams.

During the Senate Trial, it was observed that Alexander Hamilton was mentioned at least 48 times, Madison approximately 35 times, with Washington, Adams, Jefferson and Franklin receiving less love.

Hamilton in the Spotlight

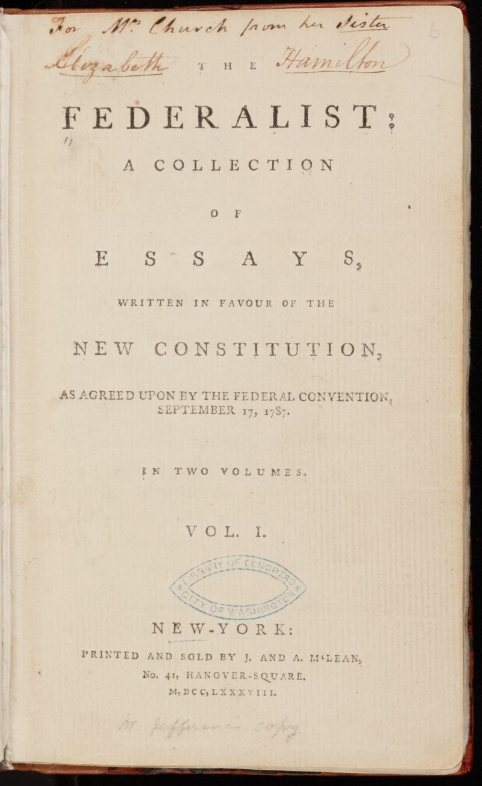

Alexander Hamilton and James Madison were the principal drafters of The Federalist Papers, eighty-five essays written between October of 1787 and August of 1788 to help convince the “People of New York” to ratify the U.S. Constitution. The Federalist Papers were written anonymously under the pseudonym Publius. A closely guarded secret, Publius’ identity did not become public until Hamilton’s death in 1804. Today scholars agree that Hamilton wrote 51 of The Federalist essays, Madison wrote 29, and John Jay, who became ill, only wrote 5 essays.

Before delving into the arguments made to the Senate, it is useful to start with the very first Federalist essay. Although it was not cited by the litigants the Trump Senate trial, Federalist No. 1 provides a “general introduction” for the “series of papers” that followed in the 84 subsequent Federalist essays. In this introductory essay, Hamilton observed that “wise and good” people can disagree even on questions of “the first magnitude to society.” This fact, Hamilton argued, should “furnish a lesson in moderation” to us all.

Citing Hamilton, Justice Neil Gorsuch makes this exact point in his recent book, A Republic If You Can Keep It. The title of Justice Gorsuch’s book is taken from a famous quote attributed to Benjamin Franklin at the close of the Constitutional Convention. As curious Americans waited on the steps of Independence Hall, Franklin was asked, “What do we have, a republic or a monarchy?” According to the oft repeated anecdote, Franklin replied, “A republic, if you can keep it. Our responsibility is to keep it.”

In Federalist No. 1, Hamilton explained the importance of ratifying the proposed constitution, which was drafted behind closed doors in Philadelphia. According to Hamilton, the consequences were “nothing less than the existence of the UNION, the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world.” Click here for a link to Federalist No. 1.

In a famous passage in his first Federalist essay, Hamilton asked the following question:

It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force. If there be any truth in the remark, the crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind.

Alexander Hamilton is widely acknowledged as a pivotal figure in President Washington’s first cabinet. He was also one of the most vocal proponents of the Constitution. Hamilton thus provides fertile material for historians, lawyers and judges to survey the founder’s thinking. It also helps that Hamilton was arguably the most prolific and productive writers of his day. According to historian Ron Chernow, Hamilton was the “foremost political pamphleteer in American history.”

Riding the storm and directing the whirlwind

The above passages from Federalist No. 1 above were not cited by the Senate trial briefs. Representative Adam B. Schiff’s Opening Statement began by quoting a letter written by Hamilton to Washington in 1792, several years after the Constitution was written. In dramatic warning to President Washington, Alexander Hamilton discussed the unlikely, but nonetheless possible danger of “popular demagogues” subverting the Constitution to pursue their personal gain.

In a letter marked “Private and Confidential,” Washington had asked Hamilton to address twenty-one criticisms that Washington had heard while traveling the country toward the end of his first term. Click here for a link to Washington’s July 29, 1792 letter to Hamilton. While Washington did not identify Jefferson by name, Ron Chernow suggests that Hamilton would clearly have known the source of the grievances Washington listed. Among the list of complaints, Washington wrote to Hamilton that critics were alleging that the real intent of Hamilton’s policies was to replace the new Constitution with a monarchy based on the British model.

In a passage quoted by both Representatives Schiff and Nadler, Hamilton rejected any suggestion that there was a plot by Hamilton or anyone else in the administration to reinstitute a monarchy. Hamilton, in his exhaustive 14,000 page letter entitled “Objections and Answers Respecting the Administration,” methodically responded to all criticisms identified by Washington. Click here for a link to Hamilton’s August 18, 1792 letter to Washington. With regard to criticism 14 in Washington’s letter, Hamilton explained the circumstances which theoretically could present a threat to our democracy:

When a man unprincipled in private life desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper, possessed of considerable talents, having the advantage of military habits—despotic in his ordinary demeanour—known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty—when such a man is seen to mount the hobby horse of popularity—to join in the cry of danger to liberty—to take every opportunity of embarrassing the General Government & bringing it under suspicion—to flatter and fall in with all the non sense of the zealots of the day—It may justly be suspected that his object is to throw things into confusion that he may “ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.”

To be sure, Hamilton did not think that this scenario was likely. But he did identify the “path” whereby a demagogue could subvert the new Republican form of government:

The truth unquestionably is, that the only path to a subversion of the republican system of the Country is, by flattering the prejudices of the people, and exciting their jealousies and apprehensions, to throw affairs into confusion, and bring on civil commotion. Tired at length of anarchy, or want of government, they may take shelter in the arms of monarchy for repose and security.

In his opening statement, Representative Schiff argued that President Trump “has acted precisely as Hamilton and his contemporaries had feared.” Of course, President Trump’s attorney, Jay Sekulow, promptly rejected this comparison. For Sekulow, the famous Hamilton quote was “inapplicable and completely out of place” since it wasn’t about impeachment and was primarily about policy disputes five years after the Constitution was adopted. “They’re not only taking the wrong law, they’re taking the wrong quotes from the Founding Fathers. . . It would be really appropriate if they cited the right provisions and what the Founding Fathers were actually talking about,” Sekulow asserted.

House Manager Gerald Nadler went even further in implicitly connecting Hamilton’s warning to President Trump. According to Representative Nadler, Hamilton’s 1792 letter was an “an especially striking portrait.” For Nadler, “Hamilton was a wise man. He foresaw dangers far ahead of his time.”

Conservative columnist William Kristol, in a piece for the now-defunct Weekly Standard, quoted the same Hamilton letter in a January 2018 article entitled “Did Alexander Hamilton Predict the Rise of Donald Trump?” It is safe to conclude that the 1792 Hamilton quote does not directly support the Democratic argument for impeachment. The quote was not written in the context of impeachment and Hamilton’s musings were addressed only to Washington. Nevertheless, at the time of this writing, it will be for the Senate to decide what the letter warned against.

In an earlier op-ed in the Wall Street Journal entitled “Hamilton Wouldn’t Impeach Trump,” attorney Alan Dershowitz hinted at the arguments that he would later make on the Senate floor. Thus, there should have been no surprise that Hamilton and the founders would be cited as authorities by both sides in the Senate trial.

Federalist 65

One of the disputed legal questions in the trial of President Trump is whether the House’s allegations of “abuse of trust” rise to the level of an impeachable offense. The most frequently cited Federalist essay, by both parties, is Federalist No. 65. Not surprisingly, Federalist No. 65 was written by Hamilton. The relevant language from Federalist No. 65 is cited below. In the remainder of this blog post sets forth the arguments by the parties in their Senate briefs citing the founding fathers.

A well-constituted court for the trial of impeachments is an object not more to be desired than difficult to be obtained in a government wholly elective. The subjects of its jurisdiction are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself. The prosecution of them, for this reason, will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused. In many cases it will connect itself with the pre-existing factions, and will enlist all their animosities, partialities, influence, and interest on one side or on the other; and in such cases there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.

Click here for a link to Federalist No. 65. While both the House Managers and the President cite to Federalist No. 65, they disagree about how to interpret it, as set forth below.

The following discussion focuses on the meaning of the term “high crimes and misdemeanors” and the specific debates by the founders in 1787 and 1788 over the impeachment power. The House Managers’ Trial Memorandum is discussed below. In Part II, the President’s Trial Brief will be discussed.

House Managers’ Trial Brief

The House Managers’ Trial Brief cites historical sources, including quotes to the founders and The Federalist Papers. Among the quoted authorities are Hamilton (cited 9 times); George Mason (cited 2 times); James Madison (cited 1 time); a letter between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson (1 time); and The Federalist Papers – No. 65, 69, and 69 (cited 6 times).

Click here for a link to the House Managers’ Trial Brief, which contains an entire background section dedicated to the “Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment.”

Copied below are selections from the House Managers’ Trial Brief:

- One of the Founding generation’s principal fears was that foreign governments would seek to manipulate American elections—the defining feature of our self-government. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams warned of “foreign Interference, Intrigue, Influence” and predicted that, “as often as Elections happen, the danger of foreign Influence recurs.” Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson dated Dec. 6, 1787.

- Fresh from their experience under British rule by a king, the Framers were concerned that corruption posed a grave threat to their new republic. As George Mason warned the other delegates to the Constitutional Convention, “if we do not provide against corruption, our government will soon be at an end.” 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, at 392 (Max Farrand ed.,1911) (Farrand).

- The Framers stressed that a President who “act[s] from some corrupt motive or other” or “willfully abus[es] his trust” must be impeached, because the President “will have great opportunitys of abusing his power.” James Iredell, speaking at the North Carolina Ratifying Convention on July 28, 1788; 2 Farrand at 67.

- The Framers recognized that a President who abuses his power to manipulate the democratic process cannot properly be held accountable by means of the very elections that he has rigged to his advantage. 2 Farrand at 65.

- The Framers specifically feared a President who abused his office by sparing “no efforts or means whatever to get himself re-elected.” 2 Farrand at 64.

- Mason asked: “Shall the man who has practised corruption & by that means procured his appointment in the first instance, be suffered to escape punishment, by repeating his guilt?” 2 Farrand at 65.

- Thus, the Framers resolved to hold the President “impeachable whilst in office” as “an essential security for the good behaviour of the Executive.” 2 Farrand at 64.

- By empowering Congress to immediately remove a President when his misconduct warrants it, the Framers established the people’s elected representatives as the ultimate check on a President whose corruption threatened our democracy and the Nation’s core interests. The Federalist No. 65 (Alexander Hamilton).

- The Framers particularly feared that foreign influence could undermine our new system of self-government. 2 Farrand at 65-66; Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson dated Dec. 6, 1787.

- In his farewell address to the Nation, President George Washington warned Americans “to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government.” Washington Farewell Address.

- Alexander Hamilton cautioned that the “most deadly adversaries of republican government” may come “chiefly from the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils.” The Federalist No. 68 (Alexander Hamilton).

- James Madison worried that a future President could “betray his trust to foreign powers,” which “might be fatal to the Republic.” 2 Farrand at 66.

- And, of particular relevance now, in their personal correspondence about “foreign Interference,” Thomas Jefferson and John Adams discussed their apprehension that “as often as Elections happen, the danger of foreign Influence recurs.” Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson dated Dec. 6, 1787.

- In drafting the Impeachment Clause, the Framers adopted a standard flexible enough to reach the full range of potential Presidential misconduct: “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” U.S. Const., Art. II, § 4.

- The decision to denote “Treason” and “Bribery” as impeachable conduct reflects the Founding-era concerns over foreign influence and corruption. But the Framers also recognized that “many great and dangerous offenses” could warrant impeachment and immediate removal of a President from office. 2 Farrand at 550.

- These “other high Crimes and Misdemeanors” provided for by the Constitution need not be indictable criminal offenses. Rather, as Hamilton explained, impeachable offenses involve an “abuse or violation of some public trust” and are of “a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated political, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.” The Federalist No. 65 (Alexander Hamilton).

- The Framers thus understood that “high crimes and misdemeanors” would encompass acts committed by public officials that inflict severe harm on the constitutional order. These issues are discussed at length in the report by the House Committee on the Judiciary. H. Rep. No. 116-346, at 28-75.

- The Framers, the courts, and past Presidents have recognized that honoring Congress’s right to information in an impeachment investigation is a critical safeguard in our system of divided powers. The Federalist No. 65 (Alexander Hamilton) (referring to the House as the “inquisitors for the nation” for purposes of impeachment).

- President Trump’s directive rejects one of the key features distinguishing our Republic from a monarchy: that “[t]he President of the United States [is] liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction . . . removed.” The Federalist No. 69 (Alexander Hamilton).

- To the extent President Trump claims that he has concealed evidence to protect the Office of the President, the Framers considered and rejected that defense. Several delegates at the Constitutional Convention warned that the impeachment power would be “destructive of [the executive’s] independence.” 2 Farrand at 67.

- But the Framers adopted an impeachment power anyway because, as Alexander Hamilton observed, “the powers relating to impeachments” are “an essential check in the hands of [Congress] upon the encroachments of the executive.” The Federalist No. 66 (Alexander Hamilton).

- When the Framers entrusted the House with the sole power of impeachment, they obviously meant to equip the House with the necessary tools to discover abuses of power by the President. Without that authority, the Impeachment Clause would fail as an effective safeguard against tyranny. A system in which the President cannot be charged with a crime, as the Department of Justice believes, and in which he can nullify the impeachment power through blanket obstruction, as President Trump has done here, is a system in which the President is above the law.

This Post continues in Part II, which discusses the Trial Brief submitted by President Trump.