History of religious freedom in Florida

Florida has a checkered, but ultimately proud history when it comes to religious freedom. This post explores the history of religious freedom in Florida, beginning before the sparsely settled territory joined the United States. The story continues through 1947, when Miami Beach adopted a first of its kind “Anti-Bias Sign Ordinance.”

The historic Miami Beach ordinance outlawed discriminatory advertising within city limits. The trail blazing ordinance was adopted at the urging of Jewish veterans returning from World War II. As described below, Miami Beach would set precedent across the nation, prior to the adoption of federal civil rights laws. The ordinance also preceded attorney Thurgood Marshall’s seminal United States Supreme Court case of Shelley v. Kraemer which held that discriminatory deed restrictions were unenforceable in the courts.

Spanish control of La Florida

In 1564, more than fifty years before the Pilgrims set sail on the Mayflower, French Huguenots established the settlement of Fort Caroline near present-day Jacksonville. At the time, La Florida was largely controlled by the Spanish, who were Catholic. The French Huguenots, who were Protestants, were fleeing religious persecution, including the particularly deadly French Wars of Religion which began in 1562.

Unfortunately, within a year, Spanish commander Pedro Menèndez de Avilès would write to Spanish King Phillip II that all of the Huguenots in Fort Caroline had been successfully eliminated. According to de Avilès’s report, he hanged “all those we found” in Fort Caroline because “they were scattering the odious Lutherance doctrine in these Provinces.” St. Augustine was established as a forward operating base by the Spanish and was used to remove the Huguenots. Two years later, the French recaptured Fort Caroline, this time slaughtering its Spanish defenders.

It is no surprise then that when Alexander Hamilton’s French Huguenot maternal grandparents arrived in the New World in 1658, they selected the British controlled island of Nevis in the British West Indies. Hamilton’s grandfather, Dr. John Faucett, and other French Huguenots were themselves fleeing religious discrimination following the revocation of the Edit of Nantes by King Louis XIV of France in 1685.

To its credit, Spanish controlled La Florida served as a refuge for runaway slaves from the American colonies. As long as they converted to Roman Catholicism and agreed to military service for Spain, runaway slaves were welcomed into Spanish Florida beginning in 1687. Of course, it was no surprise that Spain wanted loyal, freed slaves living in the area, where they served as a front-line defense against English attacks from the north and pirates by sea. Importantly, the first settlement of freed slaves in North America was established in 1738. Fort Mose (originally known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose) was strategically located two miles north of St. Augustine, the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the United States.

It is also useful to recognize that the native American Indian tribes never invited any European settlers to Florida. The largest group of indigenous peoples living in North Florida before Columbus were the Timucua. While the Catholic missionaries that eventually spread out across Florida were likely working with noble intentions on behalf of Spain, the Timucuan Rebellion of 1656 did not end well. It is estimated that the pre-Columbian population of Timucuan was approximately 200,000. By 1700, the population had been reduced to less than 1,000.

Two Treaties of Paris (1763 and 1783)

Following the American Revolution, American settlers gradually migrated west across the Appalachian Mountains and south into Florida. The trend began with the 1763 Treaty of Paris, under which Spain surrendered Florida to the British. After France lost the French and Indian War (otherwise known as the Seven Years War) lasting from 1754-1763, France surrendered its North American territories to Britain and Spain surrendered Florida. Spain would regain Florida from Britain two decades later under the 1783 Treaty of Paris, following the American Revolution.

As Britain was taking control of territories inhabited by largely Catholic populations in 1763, it wisely agreed to respect the religious freedoms of Catholic inhabitants in Canada and Florida. Section XX of the Treaty of Paris promised to grant “the liberty of the Catholick religion” and “consequently, give the most express and the most effectual orders that his new Roman Catholic subjects may profess the worship of their religion according to the rites of the Romish church, as far as the laws of Great Britain permit.”

Section XX further provided as follows:

His Britannick Majesty farther agrees, that the Spanish inhabitants, or others who had been subjects of the Catholick King in the said countries, may retire, with all safety and freedom, wherever they think proper; and may sell their estates, provided it be to his Britannick Majesty’s subjects, and bring away their effects, as well as their persons without being restrained in their emigration, under any pretence whatsoever, except that of debts, or of criminal prosecutions.

The American Revolution ended in 1783 with yet another Treaty of Paris. Negotiated by Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay, the 1783 Treaty of Paris did not specifically address religious liberties, but did attempt to protect British loyalists. Of course, both the loyalists who elected to remain in the newly liberated states and the victorious Americans largely shared similar religious views. Most British colonists and their American brothers and sisters were generally Protestants, with the exception of the large Catholic populations in Maryland.

In Article V of the 1783 treaty, the Confederation Congress promised to “earnestly recommend to the several states a reconsideration and revision of all acts or laws regarding the premises, so as to render the said laws or acts perfectly consistent not only with justice and equity but with that spirit of conciliation which on the return of the blessings of peace should universally prevail.” Article 5 also required the Continental Congress to “earnestly recommend” that the state legislatures recognize the rightful owners of all confiscated lands and “provide for the restitution of all estates, rights, and properties, which have been confiscated belonging to British subjects.” Not until the new federal Congress was established in 1789 would aspirational treaty obligations truly be binding on the states. Click here for a discussion of the legal battle to protect loyalists from discrimination and Alexander Hamilton’s legal representation of loyalist clients in New York.

Adams-Onis Treaty

The United States acquired Florida from Spain with the 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty. As evidenced by its name, the Treaty was negotiated by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and signed by President James Monroe. Under Article 5 of the treaty, the United States guaranteed “free exercise of religion without any restriction” in the former Spanish territory, which became the provinces of East and West Florida, until they were merged together in 1822.

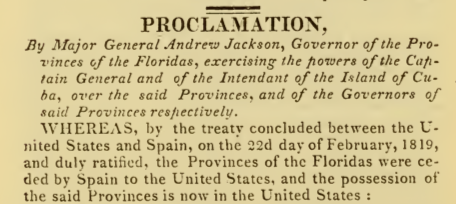

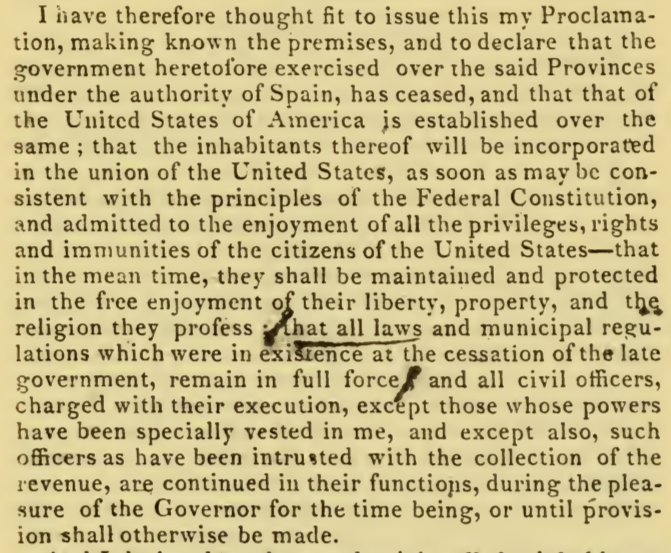

After the Adams-Onis Treaty was ratified, Major General (and Territorial Governor) Andrew Jackson issued a Proclamation on July 17, 1821 declaring that religious and other liberties would be protected. In accordance with the Treaty and U.S. law, Jackson’s proclamation promised that the inhabitants of the new Florida territory would be entitled to “the enjoyment of all the privileges of the Federal Constitution” including the “free enjoyment of their liberty, property, and the religion they profess”.

Of course, under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, freedom of religion was already protected for all Americans. Moreover, Article VI of the U.S. Constitution prohibited “religious test[s]” as a qualification for “any office or public trust under the United States.” Click here for a link to a discussion of the history of religious liberties under American law. Over time, the protections contained in the First Amendment would be interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court to apply to both the states and Federal government, under the “incorporation doctrine.” It would take another hundred years, however, before religious and racial minorities were protected from “social” discrimination by individuals and corporations.

1838 Florida Constitution and David Levy

Florida’s first constitution was adopted by a state convention of Florida territorial delegates on December 3, 1838. The Florida Constitution became fully effective on March 3, 1845 when Florida and Iowa were admitted as states into the Union, by an Act of Congress signed by President John Tyler. At the time, the population of Florida was approximately 66,000.

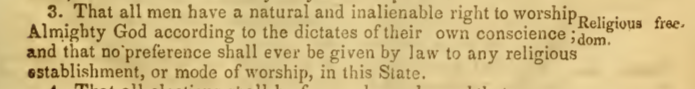

Article I, Section 1, of Florida’s 1838 Constitution provides that, “all men have a natural and inalienable right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their conscience and that no preference shall ever be given by law to any religious establishment, or mode of worship, in this State.”

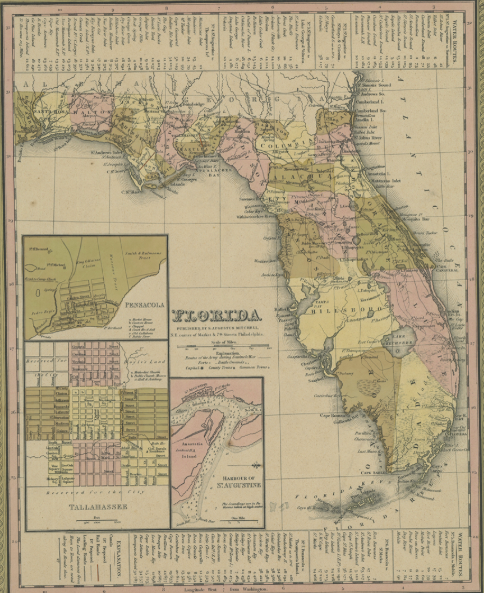

Mitchell Map circa 1845, Florida Historical Society

One of the delegates to the 1838 Florida constitutional convention was Jewish Floridian David Levy. In fact, Levy was the first Jewish American ever elected to the U.S. Senate. Serving in the territorial Florida Legislature from 1841 to 1845, Levy was a leader in the campaign for statehood. After Florida was admitted into the Union in 1845, Levy became one of Florida’s two senators, serving two terms.

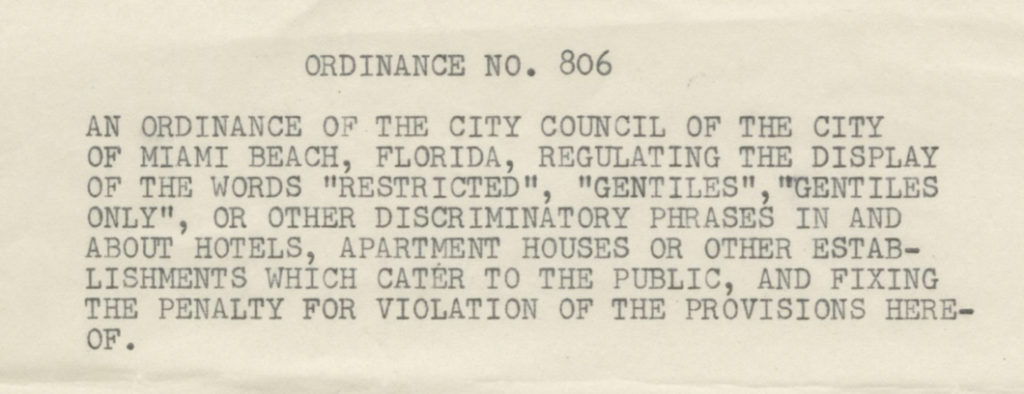

Miami Beach anti-discrimination sign Ordinance 806

While the U.S. and Florida Constitutions protected freedom of religion from adverse governmental action, private discrimination was widespread and accepted for far too long. With the memory of the Holocaust still fresh, Miami Beach anti-discrimination sign Ordinance 806 was adopted on May 7, 1947. This pioneering ordinance took big strides to eliminate private discrimination in Miami Beach.

As part of a coordinated campaign by the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith to remove discriminatory signs on Miami Beach, seventeen World War II veterans “paid quiet calls” on managers of hotels or apartment houses displaying discriminatory advertising. According to historian Gladys Rosen, these tactics proved effective as more than half of the discriminatory signs disappeared.

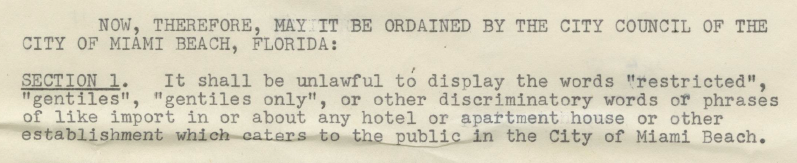

But the Anti-Defamation League and the growing class of Jewish politicians were not satisfied with only partially effective voluntary compliance. On My 7, 1947, the Miami Beach City Council unanimously approved a one-page ordinance drafted by the Anti-Defamation League that outlawed signs displaying the coded words “restricted,” “gentiles,” “gentiles only,” or other discriminatory words or phrases in any “hotel or apartment house or other establishment which caters to the public in the City of Miami Beach.” Click here for a link to a June 17, 1947 article in the Jewish Floridian newspaper.

The Florida courts, however, refused to enforce the Miami Beach Ordinance on jurisdictional grounds in a test case decided by Dade County Circuit Court Judge Stanley Milledge. The defense attorney representing the offending apartment manager asserted that the sign “had no particular meaning and merely expressed the landlord’s desire to get tenants who are ‘peaceful, genial and of good repute.’” The defense also argued that the unconstitutional ordinance deprived property owners of “free speech, free press, and the full use” of their property. The City pointed out that between 35,000 to 40,000 residents of Miami Beach were Jewish and that signs discriminating against this population were “detrimental to the general welfare.”

In ruling merely on jurisdictional grounds, Judge Milledge made clear that he did not object to the constitutionality of the ordinance, but rather had concluded that the “police powers” delegated to Miami Beach by the Florida Legislature were insufficient to support the Ordinance.

Undeterred by the ruling, the Anti-Defamation League proceeded to the Florida Legislature, as described below. Interestingly, the seminal U.S. Supreme Court case of Shelley v. Kraemer had not yet been decided. Attorney Thurgood Marshall would later prevail on behalf of J.D. and Ethel Lee Shelley in 1948 when the Supreme Court ruled that discriminatory restrictive covenants could not be enforced in the courts.

Thus, Miami Beach was ahead of the times in fighting discrimination, including racial discrimination when it adopted Ordinance 806 in 1947. The Florida Legislature corrected the jurisdictional defects with the Miami Beach ordinance in 1949, with the adoption of Chapter 26026, described below.

Chapter 26026, Laws of Florida

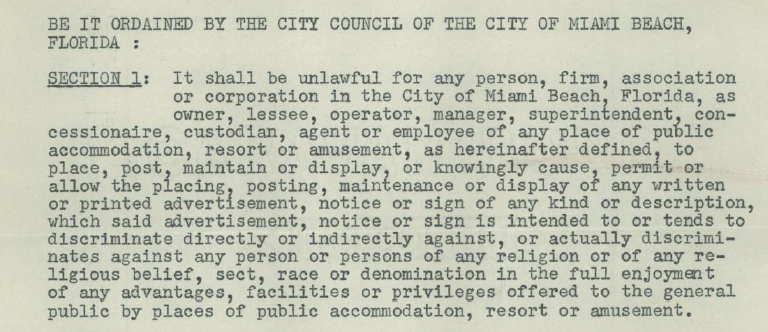

Recognizing that Judge Milledge’s ruling was not fatal to the cause, the proponents of Miami Beach Ordinance 806 took the fight to the Florida Legislature. Chapter 26026, Laws of Florida, specifically enabled Miami Beach to adopt an anti-discrimination sign ordinance. The Florida statute was adopted in May of 1949 and signed by Governor Fuller Warren.

The broadly written state statute provided authorization for Miami Beach to prohibit any “written or printed advertisement in any form or of whatever nature” that “is intended to or tends to discriminate directly or indirectly against…any person…of any religion, or of any religious belief, sect, creed, race or denomination.” The law applied to “inns, taverns, road houses, hotels, and apartment hotels,” along with restaurants, saloons, stores, barber shops, theatres, parks and similar public accommodations.

Sadly, discrimination continued for many years, but the use of discriminatory signs was now punishable by municipal law, authorized by state statute. The law was adopted due to lobbying by the Florida Regional ADL Office. The Dade County Legislative delegation unanimously endorsed the bill. The bill was written by attorney George J. Talianoff, former ADL director, in cooperation with the Miami Beach City Attorney’s Office.

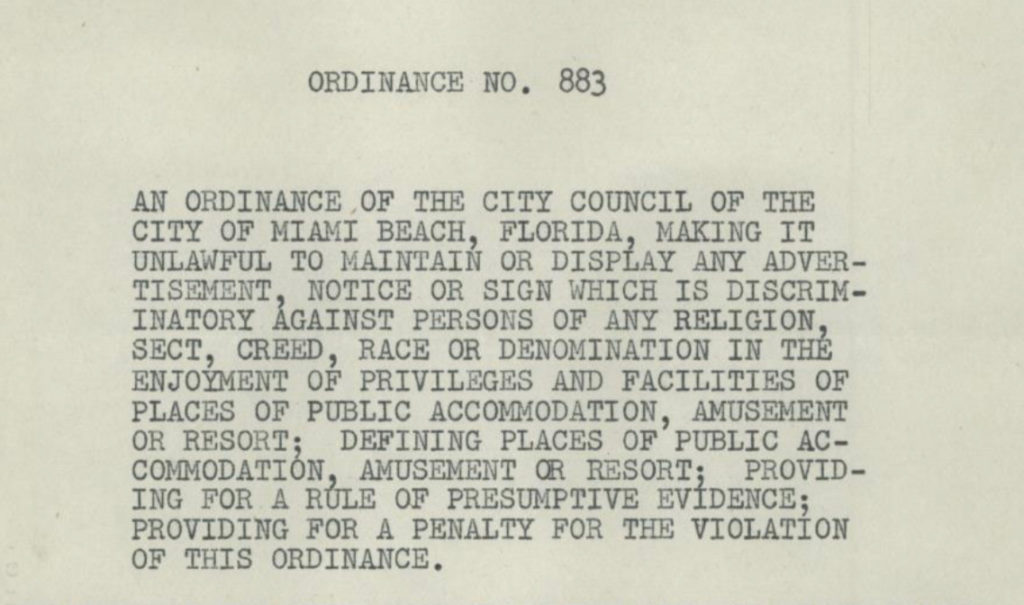

Miami Beach anti-discrimination sign Ordinance 883:

The last step was the easiest. Miami Beach anti-discrimination sign Ordinance 883 was approved on June 15, 1949. The re-adopted ordinance largely tracks the provisions of the state statute cited above.

Ordinance 883 was enforceable with a fine not exceeding $500 and imprisonment of up to 90 days in “City Jail.” As described by University of Michigan History professor Deborah Dash Moore, the Miami Beach Ordinance “reverberated as a loud rejection of discrimination.” By passing the law, the Miami Beach City Council “hung out a welcome sign for Jews, at least on Miami Beach.”

Surfside Ordinance 190

Less than two years later, the nearby Town of Surfside hung up a similar welcome sign to religious and ethnic minorities. Surfside Ordinance 190 was adopted on April 9, 1951. The comprehensive sign ordinance prohibited advertising which was “discriminatory in nature, such as the use of the words ‘Restricted’ or ‘Select Clientele.’” Building upon Miami Beach Ordinance 806 (and 883), Surfside Ordinance 190 similarly provided penalties of up to $500, or imprisonment, not to exceed 60 days.

The Surfside Ordinance was the result of educational efforts by the ADL Committee of the B’nai B’rith, North Shore Lodge. It was spearheaded by Surfside City Council member David Pollack. After the Surfside ordinance was adopted, B’nai B’rith Florida Regional Director, Gilbert J. Balkin, declared that, “Passage of this ordinance in Surfside is a notable indication of the movement to eradicate social discrimination and the blight of discriminatory displays from the State of Florida.” Click here to a June 29, 1951 article in the Jewish Floridian newspaper.

Today Florida is the third most populous state and one of the most religiously and ethnically diverse in the nation.

Click here for a discussion of the history of religious freedom in America.

Additional reading and selected sources:

Fort Caroline National Park (National Park Service)

America’s True History of Religious Tolerance (Smithsonian Magazine)

Deborah Dash Moore, Jewish Migration in Postwar America: The Case of Miami and Los Angeles

Seth Bramson, L’Chaim!: The History of the Jewish Community of Greater Miami

Frontier Religions (Florida Historical Society)

Key Dates in Colonial American Religious History (Facinghistory.org)

Jewish Heritage in Florida (Florida State Archives)

Florida Jewish Newspaper Project (George Smathers Library at UF)