Breaking News: The “Hamilton Plan” from 1787 was leaked to the press in 1798

Newly rediscovered leak suggests deeper and earlier rift between Madison and Hamilton

By: Professor John P. Kaminski, PhD, & Adam P. Levinson, Esq.

DRAFT

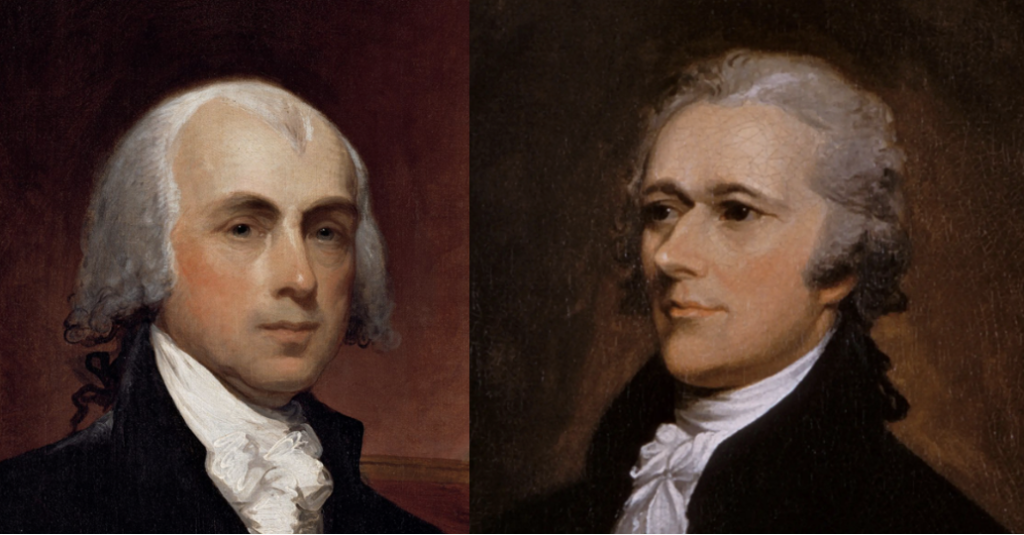

Today, the details of the “Hamilton Plan” are no secret. In addition to the more famous Virginia and New Jersey Plans, Alexander Hamilton presented his own plan at the Constitutional Convention on June 18, 1787. Under the Convention’s strict secrecy rules, members of the Convention were encouraged to speak freely as their speeches and deliberations were intended to be confidential during the Convention.

James Madison’s Convention notes were not published until 1840, after his death as the last surviving member of the Philadelphia Convention. Accordingly, historians have generally assumed that the full text of the Hamilton Plan only became public in 1840 after Madison’s death. As set forth below, recently rediscovered sources prove that the verbatim text of the Hamilton Plan was leaked to the press in January of 1798, during the vitriolic newspaper war of the 1790s.

Alexander Hamilton and James Madison were allies during the early 1780s and at the Constitutional Convention. They famously coauthored the Federalist Papers with John Jay. After the Constitution was ratified, Madison and Hamilton eventually parted company. During the Washington administration, Jefferson and Madison founded the Democratic-Republican party which opposed Hamilton’s Federalist party. Yet, the depth of the schism between Madison and Hamilton is revealed by the fact that the full text of the leaked Hamilton Plan could only have come from Madison’s papers. Whether Madison personally authorized the leak will require additional scholarship, which will be discussed in the pending book, My Most Ardent Wish: New discoveries and insights into the framing of the Constitution.

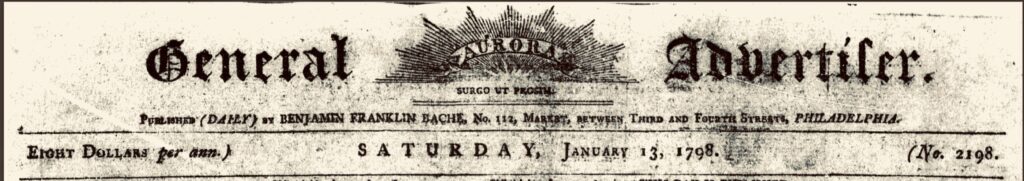

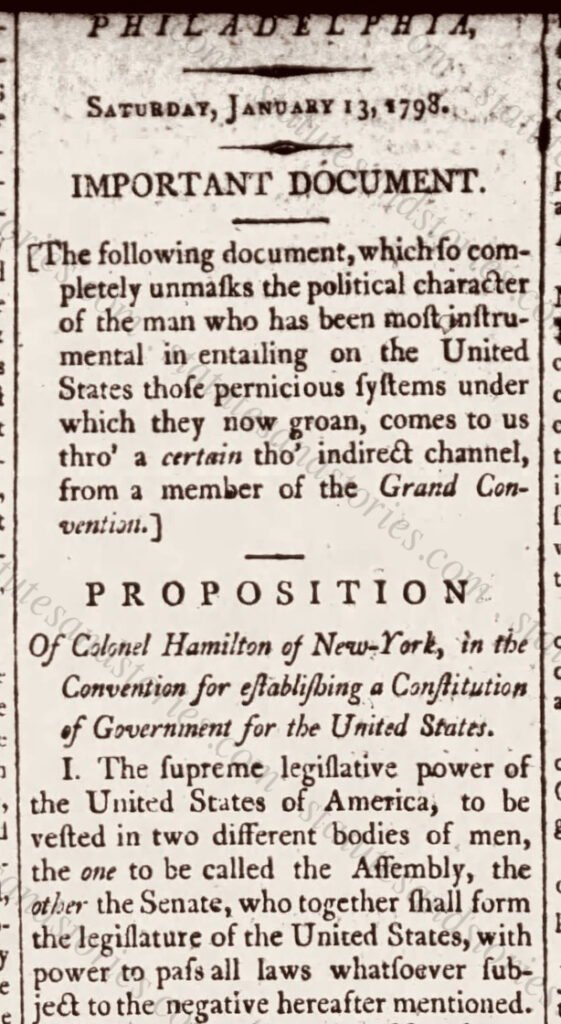

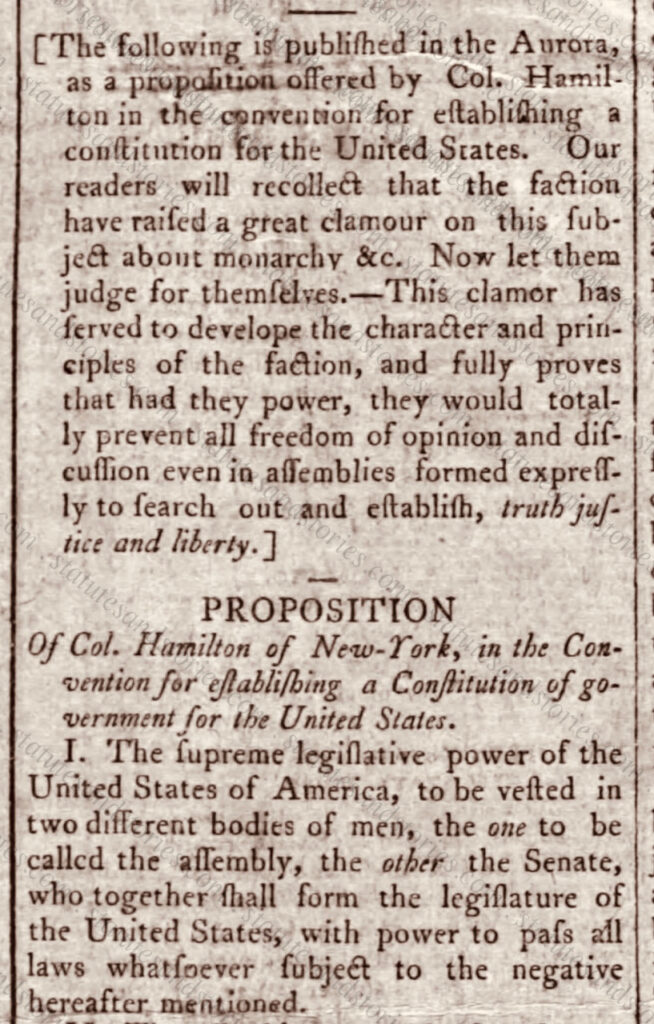

Pictured below is the leaked publication of the Hamilton Plan which was published by Benjamin Franklin Bache’s Aurora on January 13, 1798. Less than a year later Bache would die of Yellow Fever while awaiting trial under the Sedition Act. [1]

Although the Aurora newspaper did not identify the source of the leak, the introductory paragraph preceding the text of Hamilton’s Plan contains several clues. Bache’s Aurora indicates that the following “important” document “comes to us through a certain though indirect channel, from a member of the Grand Convention.” It will be up to future researchers to answer the following questions:

(i) Who was the member of the Grand Convention whose notes were leaked? The answer is almost certainly James Madison.

(ii) What was the “indirect channel” that was used to leak the Hamilton Plan to the Aurora? Note that James Monroe/John Beckley were possible henchmen working for Madison to facilitate this attack against Hamilton. By way of background, during the preceding year Beckley or Monroe were likely responsible for leaking the salacious details of Hamilton’s adulterous affair with Maria Reynolds. Hamilton vigorously defended himself against charges of corruption, but admitted to the affair when he published his notorious “Reynolds Pamphlet.” Subsequently, disagreements between Hamilton and Monroe almost led to a duel in late 1797.

(iii) Did Madison have knowledge that his notes were being leaked? Was Jefferson in on the plan? As Madison assuredly kept his Convention notes in a secure location, it is likely that he would have known if someone was seeking access to his papers. Giving Madison the benefit of the doubt, he departed Philadelphia for Virginia at the conclusion of his Congressional term in mid-1797. In theory somebody might have broken into Madison’s papers, but the culprit presumably would have needed to know what to look for and where to search.

(iv) Was there any specific event that precipitated the leak? For example, hostilities with France were increasing following the XYZ affair and the pending Quasi-War. Was the possibility of a duel between Monroe and Hamilton a precipitating factor? Was the looming election of 1800 sufficient justification to violate the Constitutional Convention’s secrecy rules?

(v) What was Hamilton’s reaction to the leak? Did he blame Madison for what could have been considered an act of dishonesty and personal betrayal?

Other newspapers that republished the leaked Hamilton Plan

Eighteenth Century newspaper archives are not exhaustive. Nevertheless, it has recently been discovered that after the Aurora published Hamilton’s Plan several Democratic-Republican newspapers quickly followed suit. In early 1798 the following newspapers republished the Hamilton Plan as a means of “unmasking” and attacking Hamilton’s “political character” as a monarchist:

- Greenleaf’s New York Journal, January 17, 1798

- The Alexandria Advertiser, January 23, 1798

- The Independent Chronicle, January 25, 1798

- The Bee, January 31, 1798

- The Albany Register, February 2, 1798

- The Poughkeepsie Journal, March 13, 1798

The Federalist leaning Gazette of the United States also republished the full text of the Hamilton Plan, but with the admonition to its readers to draw their own conclusions regarding the attacks against Hamilton. As described by Federalist John Fenno, the Democratic-Republican faction has “raised a great clamour” on the subject of “monarchy” et. cetra. For Fenno, the actions of the Democratic-Republicans proved that if they had power, “they would totally prevent all freedom of opinion and discussion even in assemblies formed expressly to search out and establish truth, justice and liberty,” namely the Constitutional Convention. Fenno’s reprinting of the Hamilton Plan in the Gazette of the United States is pictured below.

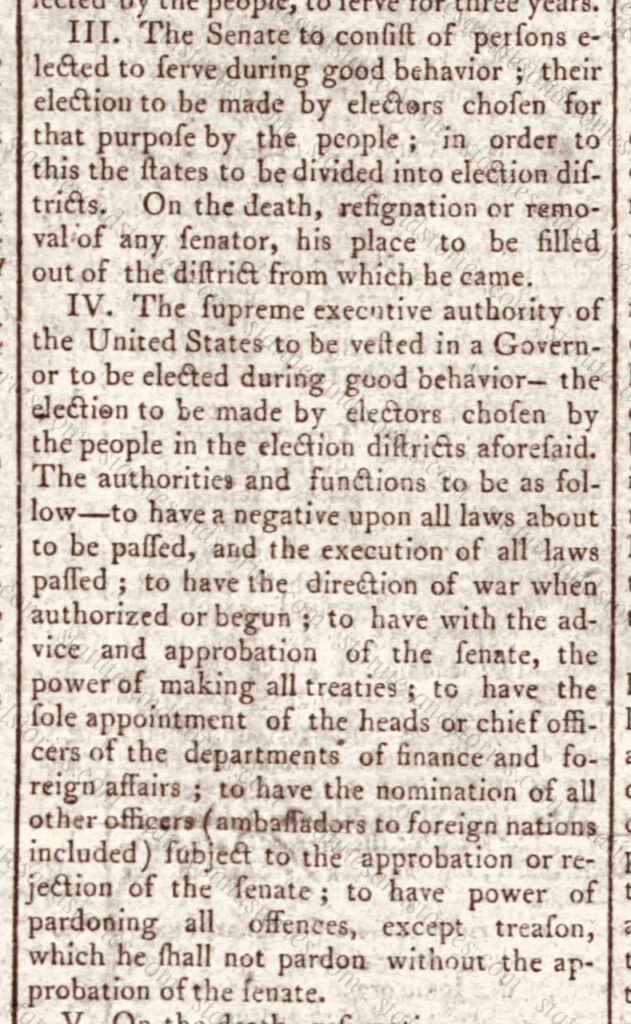

The heart of the objection to Hamilton’s Plan was no doubt sections 3 and 4 which proposed that the President and Senate would have lifetime tenure “on good behaviour.” Hamilton did not hide his admiration for the British system of government. As one of the most outspoken nationalists, he was a vocal proponent of a powerful President and energetic Federal government capable of “vigorous execution.” Nevertheless, Hamilton’s detractors ignore his proposal for a House of Representatives elected by universal male suffrage, “a proposal more democratic than that which ultimately emerged” in the final draft of the Constitution. [2]

Sections 3 and 4 of the Hamilton Plan are pictured above. Click here for a link to the full text of the Hamilton Plan. As indicated years later by Gouverneur Morris, Hamilton’s “generous indiscretion” in speaking his mind “subjected him to censure and misrepresentation.” [3]

Monarchism Allegations

In the book, Alexander Hamilton and the Persistence of Myth, Stephen F. Knott describes the common Republican tactic of accusing the Federalists of plotting to establish a monarchy. “[D]uring the twelve years of Federalist governance, ‘aristocrat’ or ‘monarchist’ was the epithet of choice hurled by the Republican opposition, despite any evidence of a Federalist scheme to establish a monarchy.” According to Knott, “[a]ccusing a public figure of being a monarchist or monocrat was the 1790’s equivalent of accusing someone of being a Communist in 1950.” [4]

As described by Hamilton and Madison biographer Richard Brookhiser, “the 1790s were a frantic time, and Madison’s paranoia on the looming threat of monarchy was not his alone.” As told by Brookhiser, “Republicans looked for monarchists under every bed, because republicanism was so new and seemed so fragile.” [5] For Brookhiser, who was himself a journalist and editor, journalism in the 1790s “was a free-for-all.” In his biography of Madison, Brookhiser indicates that newspapers had created a “modern media culture: lively, au courant, hysterical, salacious.”

Noah Feldman’s biography of Madison mentions that in 1792 the Senate had voted to put George Washington’s head on the first federal coin. James Madison was the leader of the opposition in the House which attacked this proposal as a feature of monarchy along with Hamilton’s financial plans. “It was in this environment that Madison wrote and published what would be his single strongest statement of his break from Hamilton.” According to Feldman, the goal of Madison’s essay entitled The Union: Who Are Its Real Friends? was to divide the political universe into friends and enemies of republican government. [6]

Feldman argues that by the year 1792 Madison was “[n]ot content with the claim that Hamilton was against a government of limited powers….” Madison’s essay, published in the National Gazette, described that the enemies of the union “avow or betray principles of monarchy and aristocracy in opposition to republican principles of the union, and the republican spirit of the people.” [7]

In September of 1792 Madison published another essay entitled A Candid State of the Parties, which asserted that “no doubt, some who were openly or secretly attached to monarchy and aristocracy; and hoped to make the constitution a cradle for these hereditary establishments.” For Feldman this was a reference to Hamilton. According to Feldman, “Madison believed that Hamilton’s private monarchism was becoming public policy.” [8]

Hamilton biographer Forrest McDonald writes that “[t]he task that Jefferson and Madison set for themselves was no small undertaking, for Hamilton was a national hero. His doings were immensely popular in their own right, and Washington’s sanction made them doubly so.” [9]

So the question is squarely presented: If Madison had broken with Hamilton earlier in the decade, what changed in early 1798? Why was Madison now willing to submit “proof” of the oft repeated Hamilton is a monarchist allegation which had been circulating for years?

In the months to follow Statutesandstories.com and the Center for the Study of the American Constitution invite scholars to join in a deep dive into the Madison, Jefferson and Monroe papers looking for clues as to the reason(s) for releasing the confidential Hamilton Plan. While generations of historians and biographers have written about the growing schism between Madison and Hamilton, as far as can be determined no biographer has cited the leak of the Hamilton Plan in the Aurora on January 13, 1798. [10] Why then? And to what end?

Sources:

[1] Benjamin Franklin Bache was named after his grandfather, Ben Franklin. Bache accused “the blind, bald, crippled, toothless, querulous Adams” of nepotism and monarchical ambition. He was arrested for “libeling the President & the Executive Government, in a manner tending to excite sedition, and opposition to the laws, by sundry publications and republications.” James Morton Smith, Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties (Cornell University Press, 1956) at p. 185-187; John C. Miller, Crisis in Freedom: The Alien and Sedition Acts (Little, Brown and Company, 1951) at p. 95. Bache’s Aurora was also the first paper to publish a leaked copy of Jay’s Treaty in 1795.

[2] Stephen F. Knott, Alexander Hamilton and the Persistence of Myth (University Press of Kansas, 2002) at p. 25.

[3] John C. Miller, Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox (Harper Collins, 1959) at p. 170.

[4] Knott at p. 24 & 217. Among other sources Knott cites to Donald H. Stewart, The Opposition Press of the Federalist Period (1969) 498-489 538-541.

[5] Richard Brookhiser, James Madison (Basic Books, 2011) at p. 141.

[6] Noah Feldman, The Three Lives of James Madison (Random House, 2017) at p. 354.

[7] Feldman at p. 356.

[8] Id.

[9] Forrest McDonald, Alexander Hamilton: A Biography (W. Norton & Co. 1979) at p. 238. See page 239-241 for a discussion of the newspaper attacks on Hamilton.

[10] In 1907, Max Farrand published an article in the American Historical Journal indicating that by the year 1801 the Hamilton Plan had been leaked. “Political capital was made of the fact that Hamilton was supposed to have proposed in the Convention a monarchical form of government, and in support of that contention his sketch of a plan of government, submitted in his speech of June 18, was printed at least as early as 1801, ‘with a view of destroying his popularity and influence.’ ” Farrand quotes John Franklin Jameson, Studies in the History of the Federal Convention of 1787 in the Annual Report of the American Historical Association for 1902. Jameson’s source is the first volume of William Corbett’s Porcupine’s Works in 1801, “which tell us that ’the plan of a Convention, which Mr. Hamilton…proposed to the Convention, has since been published by his enemies, with a view of destroying his popularity and influence.” In his comprehensive encyclopedia of the Constitutional Convention, John Vile cites to Farrand’s 1907 article, but no Hamilton, Madison or Jefferson biographers appear to have written about the leak of the Hamilton Plan in January of 1798.