Miss Dally’s Boarding House: Questions, Answers & More Questions (Part V)

Gouverneur Morris is widely regarded as the “penman” of the Constitution. Until recently, the location where Morris boarded during the summer of 1787 was an open question. Two hundred and thirty-five years later, following an exhaustive review of archival records, it can be safely concluded that Gouverneur Morris boarded/sublet from Miss Mary Dally in the same boarding house/property where Alexander Hamilton and Elbridge Gerry boarded during the Constitutional Convention.

Regrettably, Mary Dally’s enormously important boarding house has largely been overlooked by historians. Unlike the well-known “Declaration House” where Thomas Jefferson resided during the summer of 1776, there are no historical markers commemorating Miss Dally or her boarding house. This is unfortunate as the location where Gouverneur Morris resided in 1787 is likely the site where he “drafted” the Preamble and the September 12th draft of the Constitution. As described in a series of recent blog posts on StatutesandStories.com, newly discovered evidence helps piece together Miss Dally’s untold story.

As far as can be determined, Miss Dally did not leave behind any personal correspondence or memoirs. Scholars of the Constitutional Convention have understandably focused on the fifty-five delegates who assembled in Philadelphia between May and September of 1787. Nevertheless, clues about Miss Dally and her sister, Miss Clark, have begun to emerge from the correspondence of her famous boarders who lived together as an extended “family” for months at a time. In particular, perennial Massachusetts delegate Elbridge Gerry boarded with Miss Dally dating back to 1778 when he was attending Congress. Other long-term boarders included Philadelphia residents Gouverneur Morris and Dr. John Jones. Unlike short-term boarders, Morris and Jones may have operated law/medical offices in or alongside Miss Dally’s boarding house in four “out houses” on the property.

This blog post – Miss Dally Part V – is intended to summarize what we know – and don’t know – about Miss Dally. Part V is also an effort to identify as yet unanswered questions for further research. The emerging but disparate landscape of primary sources relating to Miss Dally is outlined for others to explore. While these records are housed in archives around the country, scanned copies have been assembled by StatutesandStories.com in support of the pending Miss Dally historical marker petition with the State of Pennsylvania. Among the questions discussed below are the following topics:

- Did Hamilton board at the same location during his three trips to Philadelphia? Alexander Hamilton made three trips to the Constitutional Convention. It remains unclear whether he boarded at the same location during all of his time in Philadelphia. Nevertheless, it is clear that he was boarding at Miss Dally’s in August and likely in September as well.

- Which delegates boarded with Miss Dally during the Constitutional Convention: Unmistakable archival evidence places three delegates at Miss Dally’s boarding house during the Constitutional Convention: Gouverneur Morris, Alexander Hamilton, and Elbridge Gerry. Given the incomplete nature of the historic record, is it possible that other delegates also boarded at Miss Dally’s during the Constitutional Convention?

- The significance of Elbridge Gerry’s letters to his wife Ann: Without any doubt, the most reliable and detailed records mentioning Miss Dally are Elbridge Gerry’s letters to his wife Ann during the summer of 1787. Ten of Gerry’s letters to Ann were published by James Hutson in 1987. Yet, as discussed below, James Hutson did not publish the full text of Gerry’s May 30 letter. Importantly, this omitted text is highly relevant to Miss Dally’s emerging story.

- Which other famous Americans boarded with Miss Dally? Miss Dally and her sister, Mrs. Clark, began housing boarders during the Revolutionary War in 1778. By providing room and board for members of the Continental Congress they would have been assisting the war effort. Doing so would also have been in keeping with the family business as their father, Gifford Dally/Dalley, worked as a tavern keeper in Philadelphia for many years, at several different famous locations.

- Miss Dally’s politics: Other than providing room and board to her guests, did Miss Dally participate in political discussions with her boarders? It is clear that over years of close interactions with members of Congress, Miss Dally developed meaningful relationships with the framers of the Constitution. Despite the Convention’s rule of secrecy, might Miss Dally have been aware of the detailed deliberations in 1787? Or was she merely a passive observer? Parisian women famously played an outsized role in the salons of 18th Century Paris? Might Miss Dally’s boarding house have afforded similar opportunities for a hostess and her sister who closely interacted with the Revolutionary Generation for well over a decade? A recently discovered letter from Dr. John Jones – which has heretofore never been published – provides remarkable insights into Miss Dally’s personal politics.

- The physical structure of the boarding house: The Philadelphia tax rolls in 1798 indicate that Miss Dally operated out of one “dwelling house” and four “out houses,” located on a 3,570-square foot property. Did the boarders reside in the out parcels, or were the out parcels used as offices by Doctor John Jones and Gouverneur Morris?

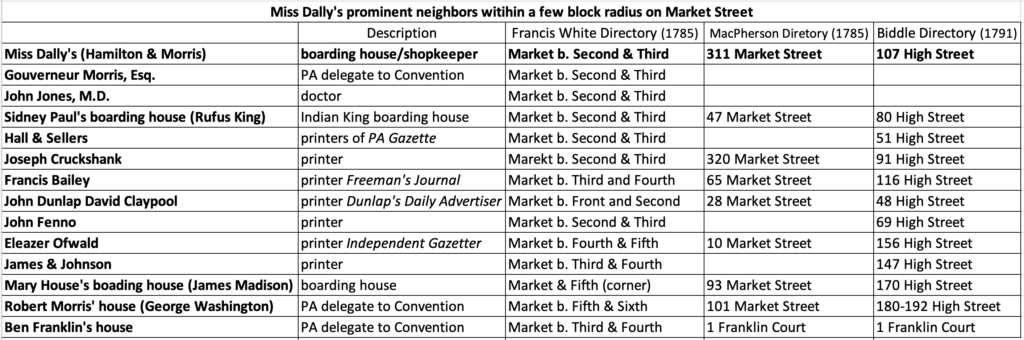

- The neighborhood: Miss Dally’s was located on the north side of Market Street near the corner of Third Street. What other taverns, lodging houses and businesses were located nearby? For example, Claypool and Dunlap, the printers for the Convention, were located only a block away on Market between Front and Second Street. Were there other reasons why Alexander Hamilton might have wanted to board with Miss Dally, apart from the proximity to Gouverneur Morris, his friend and colleague on the five-member Committee on Style?

- Who was Bartholomew Wistar (the building owner): The building where Miss Dally operated her boarding house in the 1780s and 1790s was owned by Bartholomew Wistar, a prominent Quaker. Wistar was elected to the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in April of 1787, along with Ben Franklin and Thomas Paine. Gouverneur Morris was arguably the most ardent opponent of slavery at the Constitutional Convention. Alexander Hamilton was a co-founder of the New York Manumission Society. Is it a coincidence that both Morris and Hamilton boarded at Miss Dally’s? What connections can be drawn between Gouverneur Morris, Hamilton and Wistar? Ongoing research about Bartholomew Wistar will be discussed in a pending post.

- Documentary record: Is it possible to locate additional receipts or other business records evidencing Miss Dally’s entrepreneurial activities? Might such records help flesh out Gouverneur Morris and Alexander Hamilton’s indispensable work with the Committee on Style between September 8th to September 12?

- Liberty Hall: During the Revolutionary War Miss Dally’s boarding house was known as “Liberty Hall.” The label “Liberty Hall” made sense for the location where the Massachusetts delegates to Congress were boarding. After all, Sam Adams was affectionately known as the “Life of the Cause of Liberty.” The fascinating correspondence between Congressional delegates referring to Miss Dally’s boarding house as Liberty Hall will be discussed in a subsequent post.

Miss Dally research

During the past several years StatutesandStories.com conducted wide-ranging archival research regarding Miss Dally’s boarding house. This blog post – Miss Dally Part V – is the latest installment of a multi-part series of articles outlining the resulting discoveries about Miss Dally. Accordingly, Parts I to V assemble together and discuss the largest collection of Miss Dally primary sources ever compiled (online or otherwise).

Historians have long suspected that Gouverneur Morris boarded with Miss Dally during the Constitutional Convention. Using Gouverneur Morris’ bank records at the Library of Congress, Part I confirms that Morris began boarding/sub-letting space with Miss Dally in late 1782. When he wasn’t traveling on business or visiting the family’s Morrisania estate in New York, Morris continued boarding at Miss Dally’s through September of 1787 when he acquired Morrisania from his brother. Click here for a discussion of Alexander Hamilton’s involvement in the loyalist claim and Morris family litigation involving the Morrisania estate; click here for a discussion of the complex financial transactions and arbitration which enabled Morris to purchase Morrisania.

Part II focuses on Miss Dally and her largely forgotten boarding house, which was appropriately referred to by Congressional delegates as “Liberty Hall” during the Revolutionary War. Because Miss Dally and her sister, Mrs. Clarke, operated boarding houses for approximately two decades, their names repeatedly appear in the correspondence between members of Congress. Part II uses correspondence, newspaper ads by Miss Dally, memoirs and diaries to piece together the list of founders who boarded with Miss Dally.

Part III builds on Gouverneur Morris’ bank records by compiling overlooked property tax rolls and receipts/expense reports involving Miss Dally’s boarding house. These primary sources uncovered in the Massachusetts and Pennsylvania State Archives further solidify the conclusion that Gouverneur Morris resided/sublet space in Miss Dally’s building in September of 1787 when he drafted the Preamble.

Part IV theorizes that the Committee on Style operated out of Miss Dally’s boarding house between September 8 to September 12 (hereinafter the “Committee on Style Venue Hypothesis”). While there is no direct evidence for the Committee on Style Venue Hypothesis, the body of growing circumstantial evidence suggests that Miss Dally’s boarding house was the most convenient, central location for the Committee on Style to meet when drafting the all-important September 12 draft of the Constitution, which included the Preamble.

Part V below examines the limited historical record mentioning Miss Dally. Part V is organized around a series of research topics, presented in a question-and-answer format. In other words, Part V is intended to provide a roadmap for future researchers and fellow travelers.

Part VI (pending) proposes the “Hamilton-Gerry Nexus Hypothesis” which theorizes that Alexander Hamilton collaborated with Elbridge Gerry at Miss Dally’s boarding house. Hamilton was famously one of the greatest defenders of the Constitution, whereas Elbridge Gerry was an outspoken Anti-federalist who refused to sign the Constitution. Yet, is it possible that their close quarters with Miss Dally facilitated efforts to engender compromise in the final week of the Convention? In particular, Hamilton and Gerry formed an unlikely alliance on September 10, in what may have been an orchestrated series of motions to accommodate Gerry.

Part VII (pending) presents the “Washington Gambit Hypothesis” which proposes that George Washington’s only substantive speech at the Constitutional Convention was a purposeful effort to persuade Elbridge Gerry and George Mason to sign the Constitution. The Gambit Hypothesis theorizes that George Washington’s “breaking of his silence” on the last day of the Convention was choreographed by Alexander Hamilton and Massachusetts delegates Nathaniel Gorham (the immediate past President of Congress under the Articles of Confederation) and Rufus King. If so, Washington’s gravitas and political capital as the future President of the United States was deployed in a final act of accommodation to Gerry on September 17. The Gambit Hypothesis argues that it was no coincidence that two of Gerry’s co-delegates from Massachusetts successfully obtained a last-minute amendment to make the Constitution more “republican friendly,” with George Washington’s assistance.

Thus, the Hamilton-Gerry Nexus Hypothesis and the Washington Gambit Hypothesis point to “surprising,” yet ultimately unsuccessful efforts, to achieve unanimity on September 17. Were these last-ditch efforts at compromise stage-managed from Miss Dally’s by the members of the Committee on Style (Hamilton, Morris, Madison, King and Johnson)?

Did Hamilton board at the same location during his three trips to Philadelphia?

Unlike other delegates, Alexander Hamilton made three separate trips to the Constitutional Convention. Initially Hamilton attended the Convention from mid-May through the end of June. He briefly reappeared on the Convention floor on August 13. He returned on September 6th and stayed through the close of the Convention on September 17, when he was the only New York delegate to sign the Constitution.

According to Manasseh Cutler’s famous journal, Hamilton was also sighted in Philadelphia at the Indian Queen on July 13. [1] Yet, James Madison’s notes do not indicate that Hamilton attended the Convention in July. Moreover, Hamilton only billed the state of New York for three roundtrips to the Convention, which excludes a July visit by Hamilton to the Convention. For a discussion of the audited reimbursement records submitted by Hamilton to the State of New York click here. In particular, Hamilton only billed New York for 76 day’s attendance at the Convention “three several times.”

For many years scholars of the Constitutional Convention assumed that Alexander Hamilton exclusively boarded during the Convention at the Indian Queen on Third Street between Market and Chestnut. Invariably the only source cited for this conclusion was Manasseh Cutler’s journal of July 13. According to Ron Chernow, “Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia on May 18, 1787 and joined other delegates at the Indian Queen on Fourth Street.” [2]

In his two-volume Hamilton biography, Broadus Mitchell concluded that Hamilton lodged with numerous “gentlemen of the Convention at the Indian Queen.” [3] Similarly, William Sterne Randall wrote that Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia on May 18 and “checked into the Indian Queen Tavern.” [4] Click here for a discussion of recent discoveries relating to Hamilton’s arrival in Philadelphia and his Convention attendance timeline.

As described below, Hamilton may have boarded at the Indian Queen in the early months of the Convention (May and June). Nevertheless, the record is conclusive that Hamilton boarded with Miss Dally during his August visit to Philadelphia. Hamilton likely continued boarding with Miss Dally during his return trip in September, as discussed in Part IV.

Assuming that Manasseh Cutler’s journal is accurate, Hamilton may have been boarding at the Indian Queen in July in connection with specific business unrelated to the Convention. Moreover, it is useful to note that when Hamilton initially arrived in Philadelphia in May, he began his “first” trip by attending a meeting of the Society of the Cinncinatti. Click here for a discussion of the discovery that Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia earlier than previously understood. [5]

According to the minutes of the Proceedings of the Society of the Cincinnati, the May 1787 meeting took place at Carpenter’s Hall, located near Chestnut and 4th Street. As the Indian Queen was conveniently located on 4th Street near Chestnut, it may have made sense for Hamilton to stay at the Indian Queen in May. By contrast, in September it would have been more convenient for Hamiton to stay at Miss Dally’s for purposes of collaborating with his colleagues on the Committee on Style.

Who boarded with Miss Dally during the Constitutional Convention?

Early biographers of Morris and Hamilton had only limited access to primary sources. Max Farrand’s three-volume compendium of records from the Constitutional Convention does not mention Miss Dally. Likewise, Miss Dally’s name does not appear in the 27 volumes of Hamilton papers published by Professor Syrett.

By contrast, Miss Dally’s father, Gifford Dally, was the doorkeeper for the House of Representatives when Congress resided in Philadelphia. Gifford Dally also worked as a tavern operator at various times, including managing City Tavern in 1778, the Merchant’s Coffee House in 1780, and Dally’s Hotel in 1794. Unlike her father whose name crops up in George Washington’s diary, Miss Dally’s name does not appear in the 200,000 records in the National Archive’s Founders Online database.

Reverend Manasseh Cutler of Massachusetts kept detailed notes of his travels during the summer of 1787 when he briefly visited Philadelphia and New York. One hundred years later, his grandchildren published Cutler’s journals and correspondence in 1888. In 1911, Max Farrand published what has become the seminal work aggregating all records of the Constitutional Convention, including Manasseh Cutler’s journal entry of 13 July 1787.

Reverend Cutler arrived in Philadelphia on the evening of July 12 and departed on the evening of July 14th. On July 13 Cutler was introduced to nine delegates attending the Constitutional Convention. According to Cutler’s journal entry for July 13, the following delegates were boarding together at the Indian Queen: Strong, Gorham, Madison, Mason, Martin, Williamson, Rutledge, Pinckney, and Hamilton.

Cutler may not have understood that just because these delegates were conferring/eating together at the Indian Queen on the evening of July 13 does not mean that there were boarding there. As described by Richard Beeman in the methodically researched work, Plain, Honest Men:

On almost every evening of the summer, a group of eight or more delegates dined together as a “club” – which denoted simply a regular but informal gathering of dinners…usually at either City Tavern or the Indian Queen. All the delegates were invited to join whenever they pleased, and they do not appear to have grouped themselves in any consistent sectional or ideological pattern. [6]

Moreover, Cutler is mistaken about James Madison’s lodgings. It is well established that James Madison in fact boarded at Mary House’s boarding house on 5th and Market Streets with several of his Virginian colleagues. Moreover, Cutler only visited Philadelphia for two full days. Thus, he could easily have been confused about the housing arrangements of the famous delegates who he was meeting for the first time.

The timing of when Cutler wrote his journal can also be questioned. Cutler’s journals were published by his grandchildren 100 years after the fact. According to William and Julia Cutler, “Dr. Cutler wrote out from his notes the full account of his journey to New York and Philadelphia.” It is unclear how much time elapsed between the “full account” and the original notes, which were expanded “at the request of his children.” For a critique of Cutler’s editors, see Lee Nathanial Newcomer, Manasseh Cutler’s Writings: A Note on Editorial Practice.

Whether or not Cutler is correct that Hamilton boarded at the Indian Queen in July, multiple contemporaneous letters from Elbridge Gerry definitively place Hamilton at Miss Dally’s in August of 1787. In a letter to his wife, Ann Gerry, dated August 9 Gerry explained that he just returned to Philadelphia with Colonel Hamilton. According to the August 9 letter both Hamilton and Gerry were staying at Miss Dally’s:

I arrived here, my dearest Life, about an hour ago with Colo. Hamilton, whom I met at the Hook….We are both at Miss Dally’s….

Based on the detailed correspondence between Gerry and his wife, it is unmistakably clear that Elbridge Gerry and Alexander Hamilton boarded together at Miss Dally’s in August of 1787.

The significance of Elbridge Gerry’s letters to his wife Ann

As discussed below, the most reliable and intimate primary sources mentioning Miss Dally are Elbridge Gerry’s letters to his wife Ann during the summer of 1787. Ten of Gerry’s letters to Ann were published by James Hutson in 1987. Yet, Hutson made editorial decisions not to publish the full text of Gerry’s eight-page May 30 letter to Ann. Importantly, the omitted text of the May 30 letter helps fill in significant details relevant to Miss Dally’s story.

Recently married in 1786, Elbridge Gerry and Ann were the newest parents attending the Convention. Over the course of the summer, Gerry wrote at least ten letters to Ann. It is possible to track Gerry’s changing attitude to the Convention over the summer. For example, in his August 29 letter to Ann Gerry admits that, “I have been a Spectator for some time; for I am very different in political principles from my colleagues.”

By letter dated September 1, Gerry expresses his concern for Ann’s health and mentions that he will prepare to leave Philadelphia unless she improves. “[I]ndeed I would not remain here two hours was I not under a necessity of staying to prevent my colleagues from saying that I broke up the representation, and that they were averse to an arbitrary System of Government, for such it is at present, and such they must give their voice to unless it meets with considerable alterations.” Of course, Gerry ultimately decided not to sign the Constitution on September 17th.

While Gerry’s letters have been used by historians to plumb the deliberations at the Convention, no historian has used Gerry’s letter to fill in the details of Miss Dally’s story. As discussed Part I, Miss Dally was an entrepreneurial businesswoman who sold tea in addition to operating her boarding house. In his August 9 letter Gerry discusses tea recommendations by Miss Dally. In his September 1 letter Gerry mentions that he would ask Miss Dally to assist with the purchase of silk for the Gerry family. Miss Dally’s expertise with fabric makes sense as she was listed as a tailor in Francis White’s 1785 Philadelphia Directory.

Gerry began boarding with Miss Dally when he arrived in Philadelphia in May. Because Hutson omitted substantial portions of Gerry’s May 30 letter, scholars of the Convention who have relied on James Hutson’s widely cited Supplement have not had access to the following details about Miss Dally’s boarding house.

On the third page of his May 30 letter Gerry mentions both Miss Dally and her “bespoke” tea. Because Hutson omitted Miss Dally’s name from the published excerpt of the May 30 letter, historians would not have connected the dots that Gerry was in fact boarding with Miss Dally in May. Once this important detail is filled in, the following insights from the May 30 letter become clear:

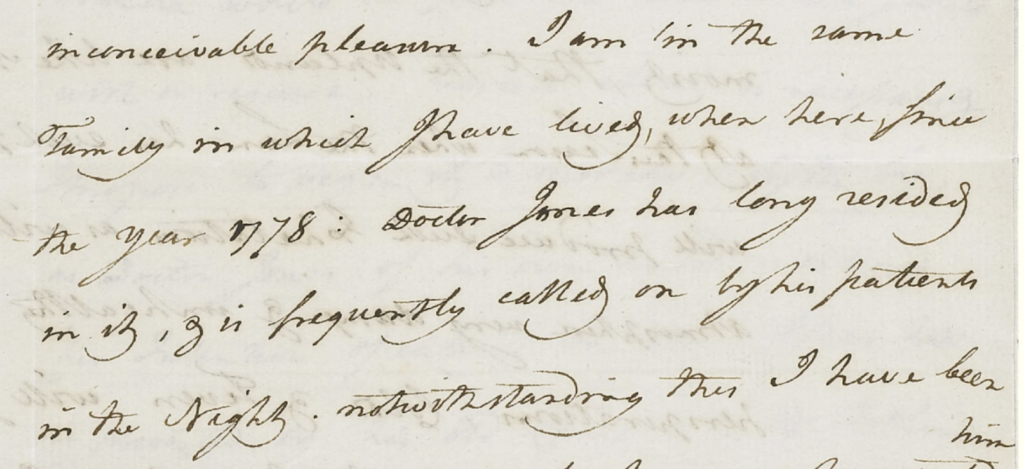

- Gerry boarded with Miss Dally in May: Gerry writes that “I am in the same Family in which I have lived, when here, since the year 1778.” This sentence makes clear that in May of 1787 Gerry had returned to Miss Dally’s, the same Philadelphia boarding house where he regularly boarded since 1778 as a delegate to Congress from Massachusetts. The fact that the Massachusetts delegation had a tradition of boarding with Miss Dally for years is discussed in Part III.

- The “same family”: By indicating that he was “in the same Family in which I have lived,” Gerry helps clarify that Miss Dally’s boarding house was a family-centric boarding house, in contrast to the larger boarding houses such as the City Tavern and the Indian Queen. An insurance survey in 1767 described the Indian Queen as covering an area forty feet deep by 21 feet wide, with two large kitchens and 16 lodging rooms on the second and third floors. [7] Similarly, the City Tavern was a large structure with a frontage of fifty feet and a depth of forty-six feet. [8] It is expected that Miss Dally’s would have been a more intimate, family setting.

- Doctor John Jones was a long-term boarder with Miss Dally: Gerry’s May 30 letter continues that “Doctor Jones has long resided in it…” As also discussed in Part III, Philadelphia property tax rolls confirm that both Dr. John Jones and Gouverneur Morris were long-term tenants of Miss Dally. Indeed, several biographers of Gouveneur Morris have noted that Morris and Dr. John Jones were good friends. It thus makes perfect sense that Morris and Jones boarded/sublet from Miss Dally.

- Nighttime visits shed light on the size of Miss Dally’s boarding house: Gerry also mentions that Dr. Jones “is frequently called on by his patients in the Night. Notwithstanding this I have been alarmed, whenever awoke by persons who wanted him, and have dreaded to hear their Business…” This suggests that Dr. Jones was not residing in one of the four “out houses” on the property, but rather was living inside the boarding house itself. While far from conclusive, this suggests that Gouverneur Morris was also residing in the same building with Gerry, Dr. Jones and other boarders.

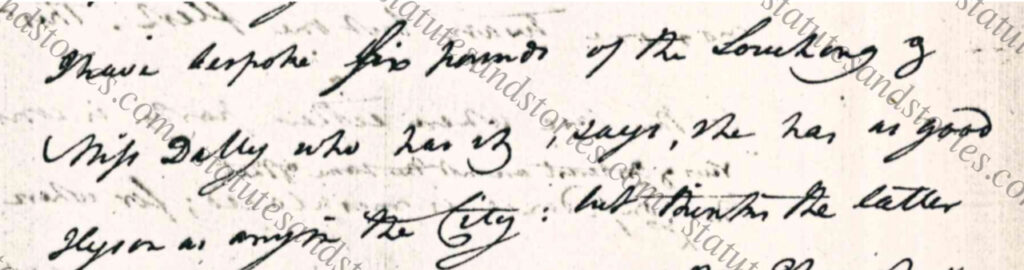

- Bespoke tea: In addition to mentioning Miss Dally by name and making clear that he is boarding with Miss Dally in May, Gerry also writes that, “I have bespoke six pound of the Soucheng [tea] & Miss Dally who has it, says she has as good Hyson as any in the City: but thinks the latter not so fresh as the other.” This detail suggests that Miss Dally isn’t just selling tea, she is selling relatively large quantities of high-quality “bespoke” tea.

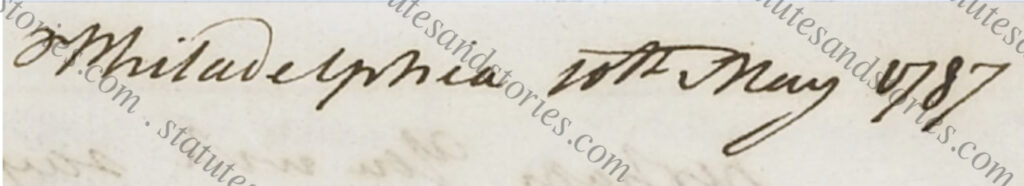

- May 30 date?: According to Hutson’s Supplement to Farrand, Gerry’s first letter to Ann is dated May 30. Yet, upon examination of the manuscript, it appears that the letter is dated May 20. If so, Gerry arrived in Philadelphia earlier than appreciated by historians. Admittedly, the handwriting is not perfectly clear, but it is hard to understand why Hutson dated the letter as May 30? One possible explanation why Hutson attributed a May 30 date is because Farrand determined that Gerry first attended the Convention on May 29. See 3 Farrand 588. Another possibility is that Hutson may have been working off of a poor quality photocopy rather than the original manuscript. Hutson himself notes on page 34 of his Supplement to Farrand that “[t]he copies of the Gerry documents that appear in this edition were acquired from the Sang Collection at Southern Illinois University, but the collection has since been sold at auction and dispersed. The present ownership of the Gerry documents is impossible to ascertain.”

Although it is now clear that Gerry began boarding with Miss Dally in May, he did not remain with Miss Dally when Ann and their newborn baby arrived later that summer. According to Manasseh Cutler’s journal, Gerry and his young wife were living on Spruce Street. Cutler’s July 13 journal entry reports that, “we took a walk to Mr. Gerry’s in Spruce street, where we breakfasted. . . . Mr. Gerry has hired a house, and lives in a family state…” The following month Gerry would escort Ann to New York. Doing so would enable Ann and their baby to escape the oppressive heat in Philadelphia, by living with her parents while Gerry remained in Philadelphia. In a letter dated August 12 to his brother Samuel, Gerry explained that he had “been to New York to accompany Mrs. Gerry and her baby, with whom this City did not very well agree.” When Gerry returned to Philadelphia he resumed boarding with Miss Dally, as evidenced by his August 9th letter which confirmed his arrival back in Philadelphia “with Colo. Hamilton.”

Which other famous Americans boarded with Miss Dally?

The Continental Congress began meeting in Philadelphia in 1774. During the Revolutionary War, the British occupied Philadelphia for approximately nine months from late September of 1777 to mid-June of 1778. The Britsh departed the city in the summer of 1778 after the French joined the war. When Congress returned to Philadelphia Miss Dally and her sister Mrs. Clark began taking in boarders. By providing room and board for members of the Continental Congress they would have been assisting the war effort. Doing so would also have been in keeping with the family business as their father, Gifford Dally, worked as a tavern keeper in Philadelphia for many years at many different locations.

While there is no evidence of any correspondence between Mary Dally and any of the founders, her name is mentioned in passing in the following primary sources discussed in Part III:

- Samuel Adams’ letter to Betsy Adams dated 13 December 1778;

- Massachusetts delegate Samuel Holten’s diary in 1778;

- Massachusetts delegate James Lovell’s letter to Nathaniel Peabody dated 3 October 1780;

- Massachusetts delegate James Lovell’s letters to Elbridge Gerry in 1781;

- Receipts/expense reports by Massachusetts delegates Samuel Adams, Artemus Ward and Samuel Holten located in the Massachusettes State Archives.

Statutes and Stories has not exhaustively evaluated correspondence to and from all Massachusetts delegates in the late 1770s to early 1780s. It is entirely possible that additional Miss Dally sightings will be uncovered in the future. Researchers are invited to assist with this exercise, particularly for correspondence back and forth to Philadelphia when Samual Adams, James Lovell, Elbridge Gerry, Artemus Ward and Samuel Holten were no longer delegates to Congress. As discussed below, a recently uncovered 1785 letter from Doctor John Jones to Elbridge Gerry is a perfect example.

Miss Dally’s personal politics and previously unpublished correspondence:

Other than providing room and board to her guests, scholars have been left to speculate whether Miss Dally participated in political discussions with her boarders/tenants? Yet, it is clear that over years of close interactions with members of Congress, Miss Dally developed meaningful relationships with the framers of the Constitution. Might Miss Dally have been aware of the specific detailed deliberations in 1787, or did her boarders rigorously follow the rule of secrecy? Was she merely a passive observer or did she offer insights from the perspective of a female business owner? Parisian women famously played an outsized role in the salons of 18th Century Paris. Might Miss Dally’s boarding house have afforded similar opportunities for a hostess and her sister, who closely interacted with Revolutionary leaders for well over a decade?

Part III contains a discussion of correspondence mentioning Miss Dally. The handful of letters were written by members of the Continental Congress beginning in 1778. For example, in a letter dated December 13, 1778 to his wife, Betsy, Samuel Adams indicated that Miss Dally and her sister “present their respectful Compliments.” This suggests that over time Miss Dally not only developed relationships with Congressional boarders but also their spouses. By far, the most detailed letters mentioning Miss Dally are Elbridge Gerry’s letters to Ann, discussed above.

Statutes and Stories.com is pleased to share for the first time previously unexplored and unpublished correspondence that shed new light on Miss Dally’s personal politics. One of Miss Dally’s long-term tenants was Dr. John Jones. Famous in his own right, Dr. Jones has been called the “father of American surgery.” Jones was the first professor of surgery in the new world, where he helped establish the medical school that would become Columbia University. Prior to the American Revolution, Jones wrote the first medical text published in America. Jones’ surgical field manual was used throughout the Revolutionary War.

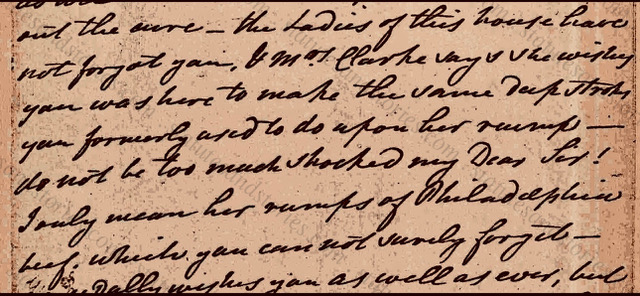

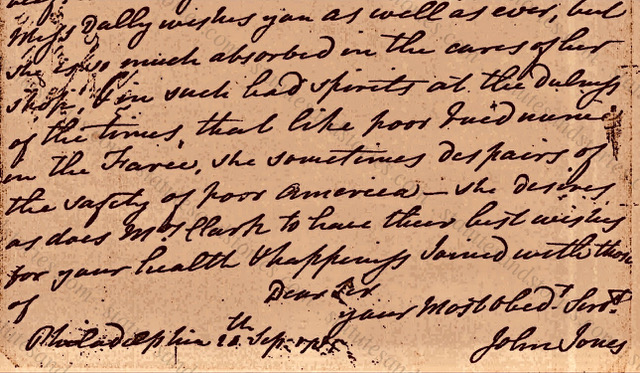

In a colorful letter dated September 20, 1785 to Elbridge Gerry, Dr. Jones shared “new” details about Miss Dally and her sister. [9] Dr. Jones likely met Gerry years earlier when they were both boarding with Miss Dally. In the September 1785 letter, Dr. Jones summarizes news from Philadelphia about Ben Franklin and other political developments. Jones mentions that he was responding to a letter from Gerry, which suggests that the two were in regular correspondence. After discussing Ben Franklin, Jones adds that Robert Morris presented his compliments and would be writing shortly.

At the end of the letter, Miss Dally and her sister make an appearance. The excerpts pictured above (and discussed below) are significant for several reasons. First, Jones indicates that “the Ladies of this house have not forgot you…” Second, Jones mentions Mrs. Clark’s cooking, indicating that “Mrs. Clark says she wishes you was [sic] here” to enjoy her “rumps of Philadelphia beef.” [10] The sense of humor by both Mrs. Clark and Dr. Jones is remarkable, suggesting a degree of familiarity that would only be expected among close friends and family. Third, Dr. Jones adds that “Miss Dally wishes you were as well as ever.” Taken together, the letter confirms that Miss Dally, her sister Mrs. Clark, and Elbridge Gerry shared longstanding friendships developed over years of living together in the same household.

Importantly, the September 20 letter from Dr. Jones provides insights into Miss Dally’s political thinking. Jones explains that Miss Dally:

is so much absorbed in the cares of her shop, and in such bad spirits at the dullness of the times, that like poor Guillaume on the Farce, she sometimes despairs of the safety of poor America.

The letter ends with Jones relaying that Miss Dally and Mrs. Clark desire to send their best wishes for your health and happiness.

Given that this may be the only extant example of Miss Dally’s “politics” it is useful to deconstruct the letter. Doctor Jones compares Miss Dally to the merchant Guillaume Joceaulme (“Guillaume”) from the famous French tragedy, La Farce of Master Pathelin (“La Farce”). Doctor Jones studied in France prior to the Revolutionary War, earning a medical degree from the University of Rheims. This may explain his familiarity with La Farce, in which Guillaume was forced to deal with both dishonest suppliers and customers. [11] Presumably this same difficulty confronted Miss Dally. This may partially explain why Miss Dally was “so much absorbed in the cares of her shop.”

It is unclear, however, why Miss Dally was in “such bad spirits at the dullness of the times.” Rather than referring to a “dull” social scene in Philadelphia, it is entirely possible that the “dullness of the times” referred to the economic conditions in 1785? Perhaps the most intriguing information in the letter is the statement that Miss Dally “sometimes despairs of the safety of poor America.” If indeed Miss Dally was despairing over the economic and political status of America, one can infer that she might have been supportive of the Federalists who would write the Constitution two years later. The fact that Miss Dally was expressing opinions about the “safety” of America similarly suggests that she was an active participant in political discussions taking place in her boarding house in 1785.

The physical structure of the boarding house:

The Philadelphia tax rolls in 1798 indicate that Miss Dally operated out of one “dwelling house” and four “outhouses,” located on a 3,570-square foot property. Did the boarders reside in the out parcels, or were the out parcels used as offices by Doctor John Jones and Gouverneur Morris?

As discussed above, the nighttime visits by Doctor Jones’ patients potentially shed light on the size of Miss Dally’s boarding house. Elbridge Gerry mentions in his May 20 (?) 1787 letter that Dr. Jones “is frequently called on by his patients in the Night. Notwithstanding this I have been alarmed, whenever awoke by persons who wanted him, and have dreaded to hear their Business…” This suggests that Dr. Jones was not residing in one of the four “out houses” on the property, but rather was living inside the boarding house itself. While far from conclusive, this suggests that Gouverneur Morris was also residing in the same building with Miss Dally, Gerry, Dr. Jones and other boarders.

The neighborhood:

Miss Dally’s was located on the north side of Market Street near the corner of Third Street. What other taverns, lodging houses and businesses were located nearby? For example, Claypool and Dunlap, the printers for the Convention, were located only a block away on Market between Front and Second Street.

The Committee on Style Venue Hypothesis – Part IV – theorizes that the Committee on Style operated out of Miss Dally’s boarding house between September 8 to September 12. There are no primary sources indicating where the Committee on Style met. Chairman Johnson’s diary only indicates the dates when the Committee met (September 8, 10th and 11th). While there is no direct evidence about the meetings of the Committee on Style, circumstantial evidence suggests that Miss Dally’s boarding house was the most convenient, central location. If so, the important September 12 draft of the Constitution, which included the Preamble, was drafted at Miss Dally’s.

Copied below is a chart of notable addresses on Market Street near Miss Dally’s boarding house.

Bartholomew Wistar, the building owner:

The building where Miss Dally operated her boarding house in the 1780s and 1790s was owned by Bartholomew Wistar, a prominent Quaker. A month before the Constitutional Convention began, Wistar was elected to the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in April of 1787, along with Ben Franklin, William Temple Franklin (Ben’s grandson), and Thomas Paine. On the floor of the Convention Gouverneur Morris called slavery the “curse of heaven on the states where it prevailed.” Morris was arguably the most ardent opponent of slavery at the Constitutional Convention. Similarly, Alexander Hamilton was a co-founder of the New York Manumission Society.

According to Richard Brookhiser, “the bitterest denunciation of slavery at the constitutional convention was uttered by Gouverneur Morris.” Historian Ron Chernow writes that “[f]ew, if any, other founding fathers opposed slavery more consistently or toiled harder to eradicate it than Hamilton.” Is it a coincidence that both Morris and Hamilton boarded at Miss Dally’s? What connections can be drawn between Gouverneur Morris, Hamilton and Wistar?

Wistar’s death:

Curiously Bartholomew Wistar died in Charleston, South Carolina in 1796 at the relatively young age of 42. Might his death have been connected to his abolitionist activities? During the late 1790s Quaker abolitionist societies were ratcheting up their public relations campaigns. Indeed, a North Carolina grand jury urgently declared in 1796 that the country “is reduced to a situation of great peril and danger” as a result of the activities of “the society of people called Quakers” which were corrupting the minds of slaves. Is it possible to link Wistar’s death in 1796 with Quaker anti-slavery activity in the South?

Documentary record:

Miss Dally’s is mentioned in Elbridge Gerry’s 1 September 1787 to Ann Gerry

Miss Dally’s is mentioned in Elbridge Gerry’s 1 September 1787 to Ann Gerry

As described above, Miss Dally’s name is repeatedly mentioned in correspondence by her famous boarders. Unfortunately, no letters to or from Miss Dally have been located thus far. Nevertheless, using the following records it is possible to sketch out Miss Dally’s story: 1) Samuel Adams’ letter to Betsy Adams dated 13 December 1778, 2) Samuel Holten’s diary in 1778, 3) James Lovell’s letter to Nathaniel Peabody dated 3 October 1780, 4) James Lovell’s letters to Elbridge Gerry in 1781, 5) receipts/expense reports by Massachusetts delegates Samuel Adams, Artemus Ward and Samuel Holten, 5) Doctor John Jones’ letter dated 20 September 1785 to Elbridge Gerry, 6) Elbridge Gerry’s correspondence with his wife on May 30 (20?), August 9 and September 1, 1787, and 7) newspaper ads in June of 1789 for Miss Dally’s tea shop.

Liberty Hall:

During the Revolutionary War several Congressional delegates referred to Miss Dally’s boarding house as “Liberty Hall.” The label “Liberty Hall” made sense as Miss Dally’s was the location where the Massachusetts Congressional delegation resided in 1778. In particular, Samuel Adams was affectionately known as the “Life of the Cause of Liberty.” [12] According to John Adams, his cousin Samuel had “the most thorough understanding of liberty…as well as the most habitual, radical Love of it.” [13] Thus, Liberty Hall was an appropriate name for Miss Dally’s boarding house, particularly when Samuel Adams was residing there.

Unanswered questions remain about the use of the “Liberty Hall” moniker. How widespread was the use of this term to refer to Miss Dally’s boarding house? Did members of the public at large refer to Miss Dally’s as Liberty Hall, or was the phrase only used by a small group of Congressional delegates? In particular, letters between Richard Henry Lee and William Whipple discussing their time and fond memories at Liberty Hall will be discussed in a subsequent post. Fellow travelers and researchers are invited to assist with this exercise.

SOURCES:

[1] Max Farrand, 3 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 at p. 58 (1911).

[2] Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton at p. 227 (2004)

[3] Broadus Mitchell, Alexander Hamilton: Youth to Maturity at 389 and n. 3 on p. 622 (1957).

[4] William Sterne Randall, Alexander Hamilton: A Life at p. 330 (2003); Jacob E. Cooke, Alexander Hamilton (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1982) at p. 48

[5] Hamilton biographers have frequently assumed that Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia on May 18 at which time he checked into the Indian Queen. Yet, the minutes of the Cincinnati make clear that he began attending the general meeting of the Cincinnati on May 17. When Professor Syrett compiled the Hamilton Papers, he included an excerpt from the Cinncinnati minutes indicating that Hamilton filed his credentials on May 18. Syrett did not mention, however, that Hamilton also attended the Cincinnati meeting on May 17. In other words, Hamilton took his seat on May 17 but “accidentally left behind” his credentials. Thus, Hamilton was undoubtedly in Philadelphia on Thursday, May 17. According to the Cincinnati minutes, meetings were consistently scheduled to begin at 9:00 every morning. As a result, it is safe to assume that Hamilton may have arrived in Philadelphia prior to 9:00 on May 17. If so, Hamilton could have attended an important dinner meeting at Ben Franklin’s house on May 16.

[6] Richard Beeman, Plain Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (Random House, 2009) at p. 78.

[7] Peter Thompson, Rum, Punch and Revolution: Taverngoing & Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia at p. 59 (1999)

[8] Thompson at p. 150.

[9] As best as can be determined, the 20 September 1785 letter from Jones to Gerry is in private hands. It was previously included in the Sang Collection, which was sold in five installments between 1978 to 1981. Fortunately, select manuscripts and/or copies of letters in the Sang Collection were retained at various institutions including Southern Illinois University, the University of Chicago, Brandeis and Yale. Periodically, letters from the Sang Collection reappear in auction catalogs.

[10] Readers are invited to appreciate Dr. Jones and Miss Clark’s humor, which would not necessarily be politically correct today.

[11] Through the use of flattery, the lawyer Pathelin convinces Guillaume — against his better judgment — to sell six yards of cloth on credit. The fact that Dr. Jones is comparing Miss Dally to the character Guillaume is interesting on several levels. Miss Dally not only sold tea and operated a boarding house, she was also a tailor. Indeed, Elbridge Gerry sought her expertise regarding fabric in 1787. It is also significant that she is being compared to a male merchant, which arguably suggests that Miss Dally could hold her own.

[12] Jack Rakove, Revolutionaries: A History of the Invention of America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) p. 54.

[13] Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 1, 1755–1770, ed. L. H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA (Harvard University Press, 1961) pp. 270–273.

James Hutson’s Supplement to Max Farrand dates Gerry’s letter to Ann as May 30, but it appears to be dated May 20 ?

James Hutson’s Supplement to Max Farrand dates Gerry’s letter to Ann as May 30, but it appears to be dated May 20 ?