Where was the Constitution drafted?

Mystery Solved: Gouverneur Morris drafted the Preamble and penultimate version of the Constitution while lodging at Miss Dally’s Boarding House on Market between 2nd and 3rd Streets

It is universally acknowledged that Gouverneur Morris “drafted” the United States Constitution in 1787. On or about September 8th, he was assigned the task of preparing the final draft of the Constitution by the Committee on Style and Arrangement. In less than four days Morris crafted the Preamble and “polished” the Constitution into its present formulation. But where did the “penman of the Constitution” draft one of the most important documents in American history? After more than two hundred and thirty-five years we now have a definitive answer.

It has long been known that Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence in the “Declaration (Graff) House” during the summer of 1776. As a member of the Second Continental Congress, Jefferson rented two furnished rooms from the owner, Jacob Graff. Today the rebuilt three-story Declaration House is a museum and tourist destination located at the corner of Market and 7th Street in Philadelphia. Jefferson’s portable desk is on display at the Smithsonian Institution. But what do we know about the drafting of the Constitution?

As described below, we can now safely answer the question where Gouverneur Morris was staying when he drafted the enduring phrase “We the People of the United States…” Based on recently revealed primary sources it is now clear that Gouverneur Morris was boarding/subletting space at Miss Dally’s/Dalley’s during the summer of 1787. Miss Dally’s boarding house was located on Market Street between Second and Third Street, only a few blocks away from Independence Hall.

This blog post – Part I – provides documentary proof where Gouverneur Morris was lodging during the summer of 1787. It is also clear that at various times during the summer of 1787 Alexander Hamilton and Elbridge Gerry also boarded with Miss Dally. Part I also discusses Gouverneur Morris’ role as a member of the Committee on Style and Arrangement selected to write the September 12 draft of the Constitution.

Part I is based on a wide-ranging investigation of Gouverneur Morris’ papers, financial records and correspondence located at the Library of Congress, the Morris Papers at Columbia University and other archives. These primary sources demonstrate that Gouverneur Morris began boarding/subletting space with Miss Dally in late 1782. When he wasn’t traveling on business Morris continued boarding at Miss Dally’s through September of 1787.

This discovery builds on research involving Gouverneur Morris’ purchase of Morrisania, the Morris family estate. Morris acquired Morrisania in April of 1787 following the death of Gouverneur Morris’ mother, Sarah, in January of 1786. Click here for a discussion of the protracted process by which Morris acquired Morrisania in the months leading up to the Constitutional Convention.

Part II focuses on Miss Dally and her largely forgotten boarding house. Following an exhaustive analysis of available primary sources it is now possible, for the first time, to paint a more complete picture about Miss Dally. Part II uses correspondence between delegates at the Constitutional Convention, newspaper ads by Miss Dally, memoirs, and diaries to piece together as much as can be learned about Miss Dally and her sister, Mrs. Clarke. Because Miss Dally and her sister had operated their boarding house for a decade, their names appear in the correspondence between members of Congress as early as 1778. In fact, Miss Dally’s lodging house was appropriately referred to by Congressman William Whipple as “Liberty Hall.”

Part III builds on Gouverneur Morris’ bank records by compiling overlooked property tax rolls and receipts/expense reports involving Miss Dally’s boarding house. These primary sources uncovered in the Massachusetts and Pennsylvania State Archives further solidify the conclusion that Gouverneur Morris resided in Miss Dally’s building in September of 1787 when he drafted the Preamble.

Part IV theorizes that the Committee on Style operated out of Miss Dally’s boarding house between September 8 to September 12 (hereinafter the “Committee on Style Venue Hypothesis”). While there is no direct evidence for the Committee on Style Venue Hypothesis, the body of growing circumstantial evidence suggests that Miss Dally’s boarding house was the most convenient, central location for the Committee on Style to meet when drafting the all-important September 12 draft of the Constitution, which included the Preamble.

Part V identifies unanswered questions for further research. For example, who else boarded with Miss Dally in 1787? What other taverns, lodging houses and businesses were located near Miss Dally’s? It is possible to locate more receipts or other records which might help flesh out the work of the Committee on Style between September 8th to September 12? Historians and researchers are invited to explore these and other questions.

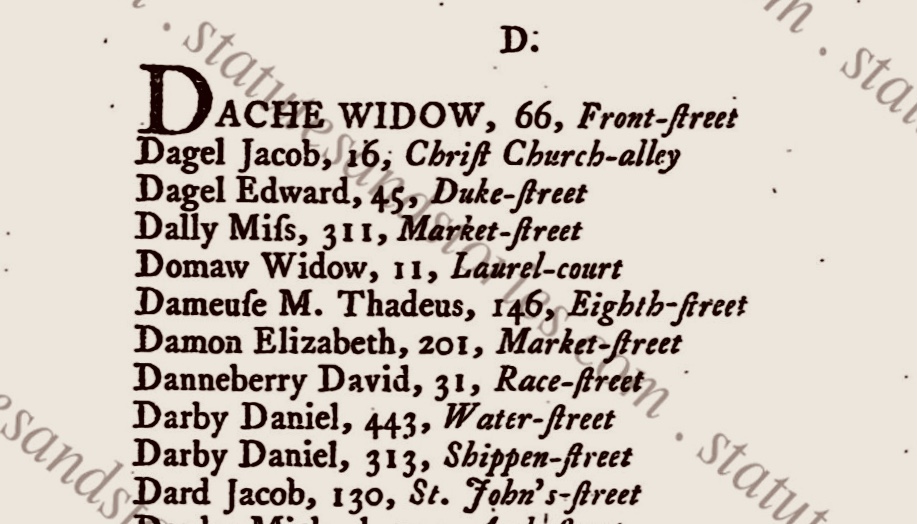

According to Philadelphia’s first city “directory” printed in 1785, “Dally Mifs” resided at “311 Market-ftreet.” Is it possible to build a consensus that a historic marker for Miss Dally’s boarding house should be affixed to an appropriate location on Market between Second and Third Streets in Philadelphia? The historic location where the Preamble was drafted deserves no less.

Background about the drafting of the Constitution

On June 11, 1776, the Second Continental Congress appointed five members to draft the Declaration of Independence. The members of the “Committee of Five” (John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston) selected Thomas Jefferson to prepare the initial draft. Between June 12 and June 27, Jefferson drafted the Declaration, which was presented to Congress in the Pennsylvania State House on June 28th. Famously, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence in what is now known as Independence Hall on July 4, 1776.

Eleven years later, on September 17, 1787, thirty-nine members of the Constitutional Convention signed their names to the Constitution. Meeting in Philadelphia at the same location where the Declaration of Independence was approved, the Constitutional Convention voted to send the Constitution to the states for ratification. The rest is history. But who “drafted” the Constitution and where in Philadelphia did he do it?

It is widely accepted by historians that Gouverneur Morris (pictured above) was the “penman” of the United States Constitution. Two years before his death, Morris took credit for writing the Constitution. In a letter to Timothy Pickering dated December 12, 1814, Morris admitted that the Constitution “was written by the fingers, which write this letter.” Click here for a link to Morris’ letter.

No less authority than James Madison, the so-called “father of the Constitution” agreed that “[t]he finish given to the style and arrangement of the Constitution fairly belongs to the pen of Mr. Morris.” Madison further acknowledged that “[a] better choice could not have been made, as the performance of the task proved.” Click here for a link to Madison’s letter to historian Jared Sparks. At the time, Sparks was researching the drafting of the Constitution for a biography about Gouverneur Morris. Accordingly, there is little doubt that Morris’ title as the “penman of the Constitution” is well deserved.

As was the case with the Declaration of Independence, the drafting of the final version of the Constitution was delegated to a five-member committee. On September 8th, the Constitutional Convention appointed the Committee on Style and Arrangement to “revise the stile and arrange the articles which had been agreed to by the House.” The five-member committee consisted of four young nationalists (Gouverneur Morris, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, Rufus King) and Chairman William Samuel Johnson.

According to Chairman Johnson’s diary the Committee met for the first time on the evening of Saturday, September 8th. It is likely that at this initial committee meeting Gouverneur Morris was selected to draft the Constitution. According to Madison, “the task having, probably, been handed over to him by the Chairman of the Committee, himself a highly respectable member, and with the ready concurrence of the others.” The Committee delivered its draft to the Convention on Wednesday, September 12. Accordingly, Gouverneur Morris and the Committee on Style and Arangement used a four-day window between September 8 and September 11 to prepare the draft submitted on September 12.

Of course, Morris did not start from scratch when he drafted the Constitution. From May through September the Convention approved twenty-three articles which had travelled through the predecessor Committee of Detail. Morris’ job was to organize and arrange the summer’s work into a coherent “plan.” Here, Morris shined. He distilled twenty-three disjointed articles that he inherited into the seven cohesive articles that constitute a logical, coherent blueprint for a functioning government. And most famously, Morris deserves credit for crafting the Preamble.

According to Morris biographer Richard Brookhiser, the prior version of the Preamble “was as plain as paint” and did not opine “what the ends of government might be.” As described by Brookhiser, Morris’ revisions were momentous:

Morris’s Preamble names “the people,” rather than the thirteen states, as the source of legitimacy and power…. When Morris changed “We the people of the states” into “We the people,” he created a phrase that would ring throughout American history, defining every American as part of a single whole.

So where did Gouverneur Morris craft one of the most famous phrases in American history? Where was Morris lodging from September 8 to September 12 when he drafted the Constitution?

Finding Gouverneur Morris: The Park Service Bicentennial Map of Philadelphia

In preparation for the Bicentennial of the Constitution in 1987, researchers at the National Park Service and the Library of Congress scoured through old manuscripts and records. Their work resulted in a map of Philadelphia created by historian Anna Coxe Toogood and artist Bob Terrio. The “Philadelphia, 1787” map was prepared for a packet titled, Celebrating the Constitution 1787-1987. Among other things, the map depicts the locations where delegates were believed to have boarded during the summer of 1787.

The “Philadelphia, 1787” map indicates that Gouverneur Morris, Alexander Hamilton and Elbridge Gerry boarded at Miss Dally’s boarding house. Unfortunately, the map doesn’t cite to any primary sources.

At the same time that the “Philadephia, 1787” map was being prepared, Toogood and approximately forty historians and researchers from the National Park Service and other research institutions collaborated on an influential book: 1787: The day-to-day story of the Constitutional Convention, published by the Independence National Historical Park in 1987. Yet, the 1787 book is silent on the location where Morris boarded in 1787.

Another enormously important book was published in 1987 by James Hutson and Leonard Rapport. Hutson, the Chief of the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, and Rapport, a storied researcher with the National Archives, teamed up to update Max Farrand’s three-volume classic, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787.

Hutson’s Supplement to Farrand sought to collect all documentary material relating to the Constitutional Convention discovered since the publication of Farrand’s authoritative work in 1911. Nevertheless, Hutson’s Supplement does not contain any hint about where Gouverneur Morris was boarding in the summer of 1787. By contrast, Hutson’s Supplement contains a letter from Elbridge Gerry indicating that Hamilton and Gerry were both staying “at Miss Dally’s.” Gerry’s letter to his wife Ann Gerry dated August 9 will be discussed in Part II.

Relying only on the “Philadelphia, 1787” map several historians have taken for granted that Morris was boarding at Miss Dally’s with Hamilton and Gerry. John R. Vile’s two-volume encyclopedia of the Constitutional Convention contains a section discussing the “Lodging of the Delegates.” Vile summarizes available information about Philadelphia’s boarding houses, including the names of delegates who stayed at Mary House’s Boarding House, the Indian Queen, Mrs. Marshall’s Boarding House, and “Mrs. Dailey’s.”

Peter Charles Hoffer wrote an entire book about the Preamble. Hoffer’s book, For Ourselves and Our Posterity, dedicates a chapter to Miss Dally. Hoffer’s prologue envisions “Dinner at Mrs. Dailey’s Boarding House.” Yet, other than citing to the “Philadephia, 1787” map and those who rely on the map, no published work has provided any documentary proof that Gouverneur Morris was in fact staying at Miss Dally’s.

The conventional wisdom is correct – Morris boarded with Miss Dally

Since 1987 historians have routinely assumed that Gouverneur Morris was boarding with Miss Dally in 1787. While no documentary proof has been published to support this claim, the conventional understanding is correct. Gouverneur Morris’ bank records provide compelling evidence that he consistently boarded with Miss Dally for years, dating back to 1782. These financial records are reinforced by the fact that Philadelphia directories published in 1785 provide the same address for Morris and Miss Dally.

The Gouverneur Morris Papers are housed in 26 containers at the Library of Congress. The collection was microfilmed in the 1960s. Among Morris’ papers, in box 20, are Morris’ meticulous bank books which run from 1782 to 1788.

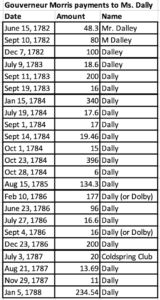

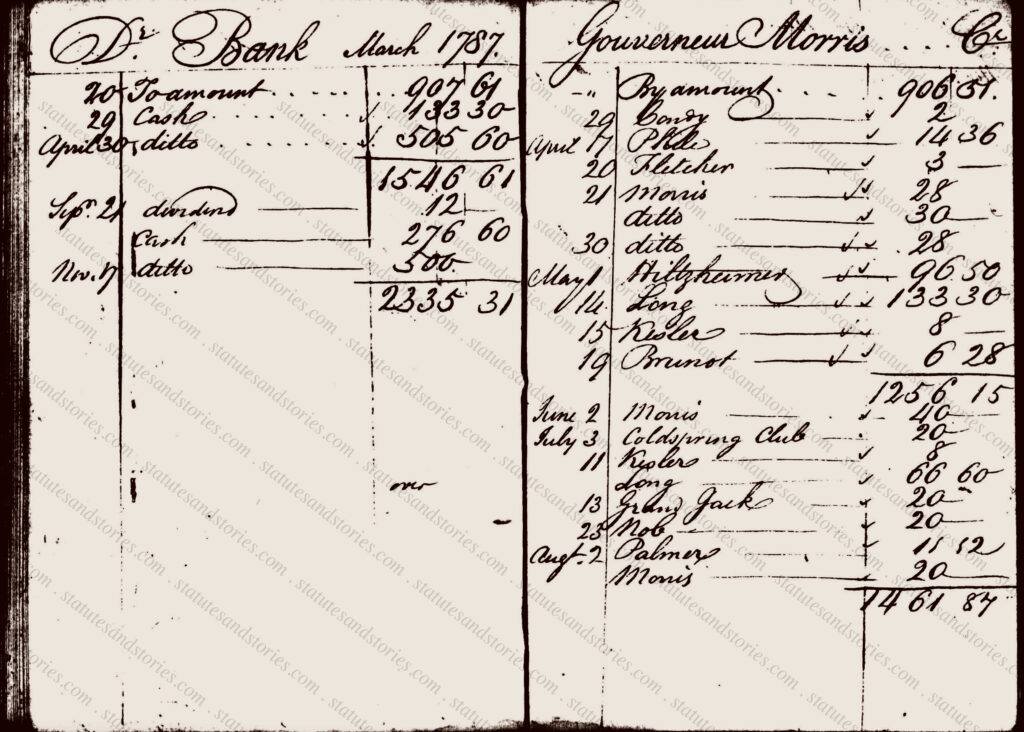

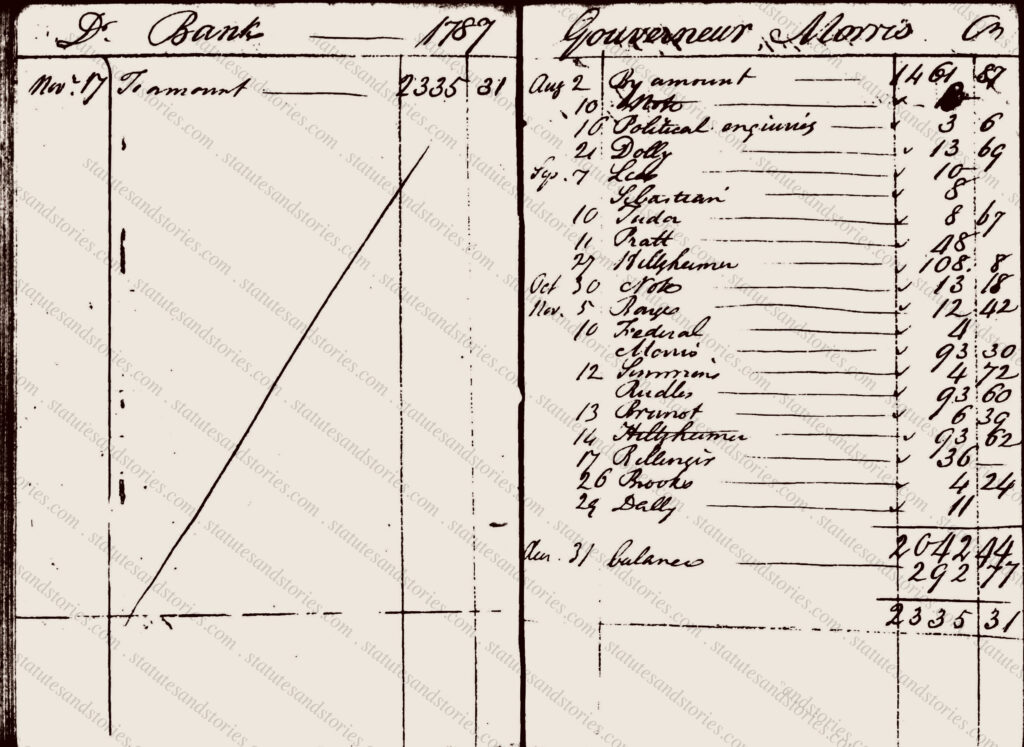

As illustrated by the following chart Morris began boarding with Miss Dally as early as June of 1782. While Gouverneur Morris initially spelled the name Dally with an “e” in 1782 and 1783, the name “Dally” consistently appears in Morris’ bank books through 1788. As far as can be determined, no biographer or researcher has systematically reviewed Morris’ financial records to validate where Morris lived during this period – until now.

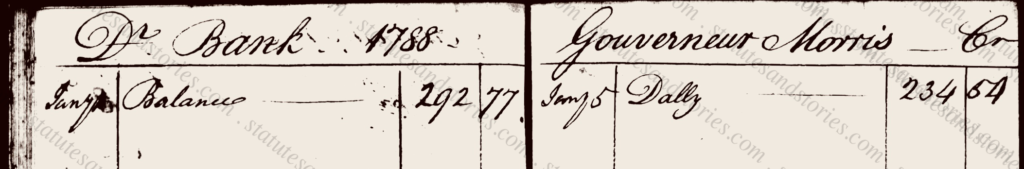

The Constitutional Convention met from May 14, 1787 through September 17, 1787. Interestingly, there are no meaningful payments to Miss Dally during the Convention. Yet, on January 5, 1788, Gouverneur Morris owed Miss Dally $234.54, which sum likely reflects a year’s worth of room and board.

Why would Gouverneur Morris have been so late in making payments to Miss Dally? The answer involves Gouverneur Morris’ purchase of Morrisania in April of 1787. Gouverneur Morris was forced to take out substantial loans of more than £7,000 to acquire his family estate from his brother, Staats Long Morris. Click here for a link to a discussion about the purchase of Morrisania. It would appear that Miss Dally was willing to extend credit to Gouverneur Morris because he had been a long-term client. And she likely knew that he was a good credit risk.

Pictured below is Morris’ bank book entry for January of 1788 reflecting a balance due to Miss Dally of $234.54. On January 5, 1788 Morris paid off the $234.54 balance. As far as can be determined none of the other itemized payments identified by Morris in 1787 during the Convention were credited to the owners of other boarding houses. In other words, there is no evidence that Morris boarded at any other boarding houses in Philadelphia, other than Miss Dally’s. Indeed, during the year 1787 Gouverneur Morris accumulated a sizable debt to Miss Dally of $234. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that Morris boarded with Miss Dally in September of 1787, as he had been doing since 1782.

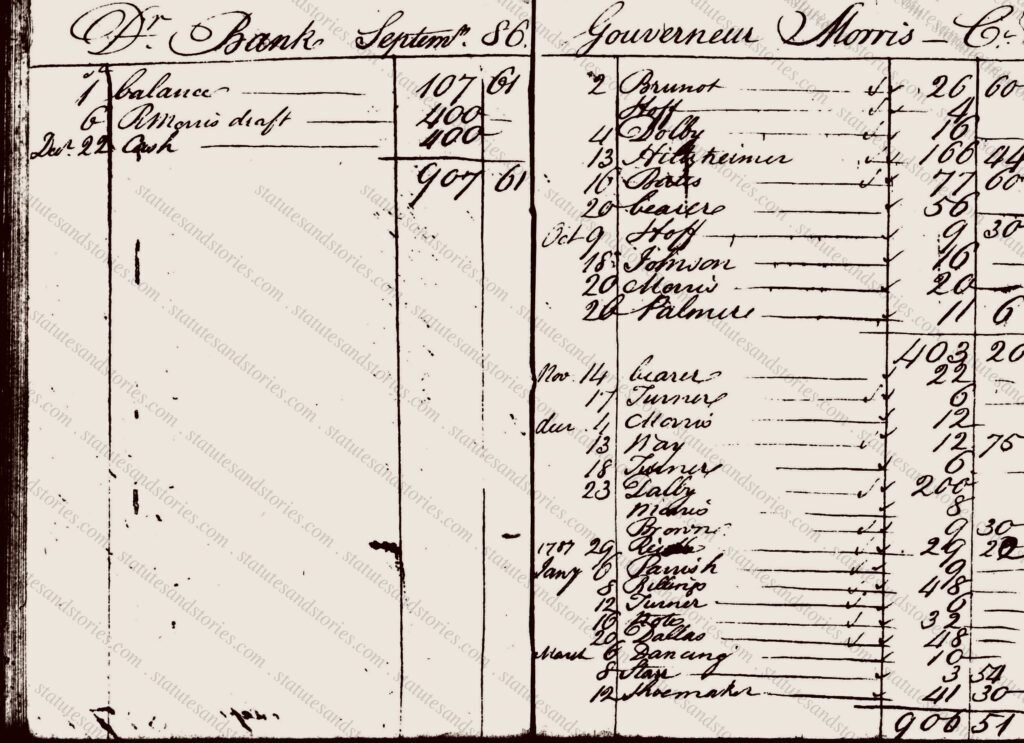

Based on the above chart it appears that the monthly boarding charge was approximately $16 in 1786. For example, Morris paid $16.6 to Miss Daily on July 27, 1786. A month earlier, Morris paid $96 on June 23, 1786. This $96 payment could represent 6 months of lodging ($96/$16 per month = 6 months). On September 4 Morris paid another $16. Morris ended the year 1786 by paying $200 to Miss Daily, which presumably covered his arrears for the year.

Following the December 23, 1786 payment, Morris pays the unusual sum of $13.69 on August 21, 1787. It is unclear what this smaller payment represents, but it is entirely possible that it represents an out-of-pocket expense charged by Miss Dally. Another charge of $11 is paid on November 29, 1787. No additional payments are made by Morris to Miss Daily until the $234.54 payment on January 5, 1788.

While additional research would be necessary to confirm the following speculation, it is entirely possible that the sum of $234 paid on January 5, 1788 represents 13 months at $18 per month ($234/$18 per month = 13 months). Or, the $234 might include additional interest or other charges. With that said, Morris temporarily departed the Convention in late May to attend to his new estate in Morrisania (and other business), returning to the Convention on July 2. When the Convention finally adjourned on September 17, Morris returned to his new home in Morrisania. It is unclear when Morris ultimately moved into Morrisania and permanently left Philadelphia.

Copied below are Morris’ bank book pages from September of 1786 to January of 1788. Statutesandstories.com invites others to assist with a more exhaustive audit of Morris’ finances for further clues.

An entry of $20 paid for the “Coldspring Club” on July 3, 1787 is particularly noteworthy. The Coldspring club was a dinner club of delegates who would share dinner expenses when they ate together. Washington regularly attended this dinner club every seven days. According to George Washington’s diary, Washington dined with the ColdSprings Club on the following dates: June 30, July 7, July 14, July 21, July 28, August 11, August 25 and September 8.

The September 8th date is significant. If Gouverneur Morris also dined with the Coldsprings Club on September 8th, both Washington and Morris would have been having dinner together on the same day that the Committee of Style and Arrangement had its first meeting? Who else attended this dinner?

William Samuel Johnson’s diary for September 8th reads as follows: “in Conventn. Dind. Mifflins. Eveng. Comee.” In other words, on September 8th Johnson attended the Convention during the day, had dinner with Thomas Mifflin (one of the delegates from Philadelphia) and then attended the first meeting of the Committee of Style in the evening. This means that Chairman Johnson likely did not dine with Washington or Gouverneur Morris before the first committee meeting of the Committee of Style on the evening of September 8th. This begs the question who else attended dinner with the Coldspring Club? Did Hamilton, Madison, or other committee members?

These and other questions will be discussed in Part III. Click here and here for a discussion of the Hamilton Authorship Thesis which focuses on coordination between Gouverneur Morris and Alexander Hamilton during the summer of 1787 and the possibility that Alexander Hamilton wrote the Constitution’s 17 September Cover Letter.

Miss Dally’s Boarding House

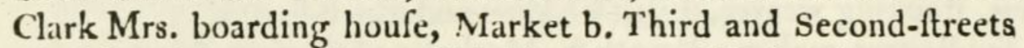

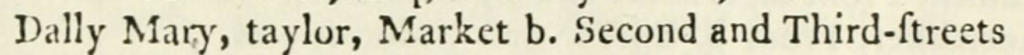

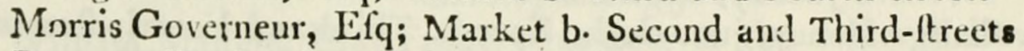

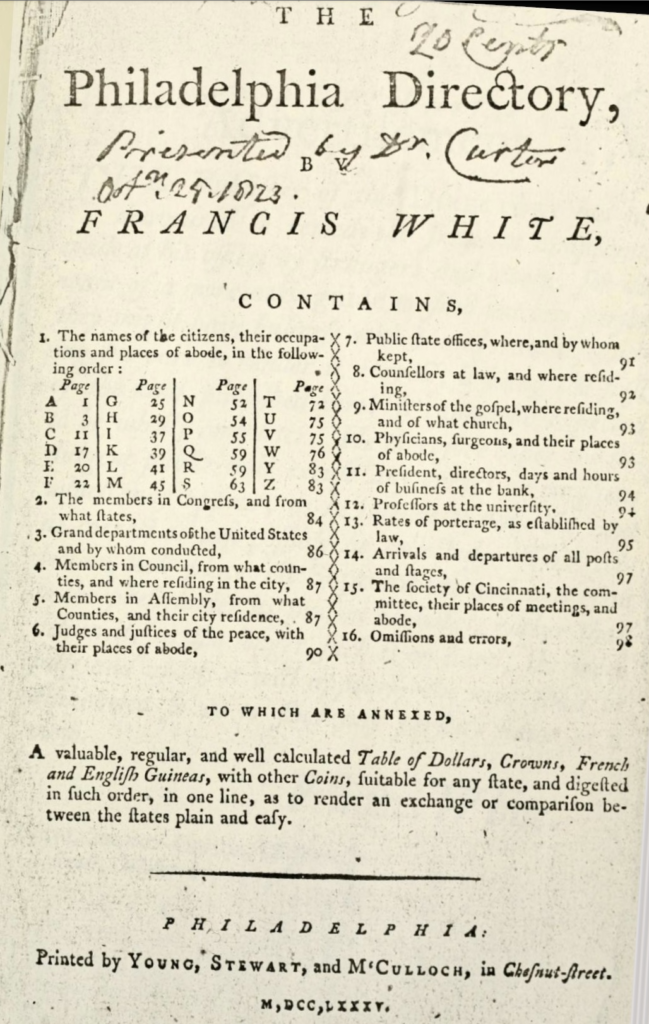

According to The Philadelphia Directory published by Francis White in 1785, Miss Dally’s boarding house was located on Market Street between Second and Third Street. This address matches the more specific street number – 311 Market Street – assigned by MacPherson’s Directory of the City and Suburbs of Philadelphia which was also published in 1785.

As described by the website Philahistory.net:

In 1785, in the foremost city in the two-year-old United States, two Philadelphia men raced to put out the first-ever city directory in America. Each took a different approach. Francis White gave almost everyone’s profession, but listed only the street and block they lived on, dealt more or less only with the city proper (back then, only between South Street and Vine) and at that, failed to list everyone. Captain John MacPherson was more methodical but less practical. He listed everyone, even those who refused to give their name or who gave impudent answers, and gave the professions only of subscribers. He was also the first to assign numbers to Philadelphia houses, but in doing so went straight up one side of a street and down the other, so that 1 Arch Street might be across the street from 300 Arch Street. He also assigned numbers to outbuildings such as stables and other utilitarian structures, and to where he thought houses might some day be built. S

Significantly, Francis White’s Directory lists the same address for Mary Dally and Gouverneur Morris: Market Street between Second and Third. Miss Dally’s sister, Mrs. Clark, is similarly listed as residing at Market between Third and Second. The fact that Mary Dally is described as a taylor is not surprising. In one of Elbridge Gerry’s letters to his wife, Gerry indicates that he would consult with Miss Dally about silk for a suit. Click here for a link to Gerry’s letter of September 1, 1787 to Ann Gerry.

This post continues in Part II with a discussion about Miss Dally. Although she has been overlooked for decades, her boarding house was referred to as “Liberty Hall” when the Massachusetts delegates to Congress boarded with Miss Dally in 1778.

Part III builds on Gouverneur Morris’ bank records by compiling overlooked property tax rolls and receipts/expense reports involving Miss Dally’s boarding house. These primary sources uncovered in the Massachusetts and Pennsylvania State Archives further solidify the conclusion that Gouverneur Morris resided/sublet space in Miss Dally’s building in September of 1787 when he drafted the Preamble.

Part IV theorizes that the Committee on Style operated out of Miss Dally’s boarding house between September 8 to September 12 (hereinafter the “Committee on Style Venue Hypothesis”). While there is no direct evidence for the Committee on Style Venue Hypothesis, the body of growing circumstantial evidence suggests that Miss Dally’s boarding house was the most convenient, central location for the Committee on Style to meet when drafting the all-important September 12 draft of the Constitution, which included the Preamble.

Part V examines the limited historical record mentioning Miss Dally. Part V is organized around a series of research topics, presented in a question-and-answer format. In other words, Part V is intended to provide a roadmap for future researchers and fellow travelers.

Miss Dally’s boarding house comes to life in a remarkable series of letters between New Hampshire Congressional delegate William Whipple and Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee which are discussed in Part VIII. The “Whipple – Lee correspondence” illustrates the deep friendships that were forged around Miss Dally’s hearth. Massachusetts delegates, including Samuel Adams, began boarding with Miss Dally in 1778 during the Revolutionary War. Members of the founding generation continued boarding with Miss Dally during and after the Constitutional Convention.

Additional correspondence relating to Miss Dally’s boarding house is discussed in Part IX. Finally, Part X presents the long-sought receipt from Miss Dally to Gouverneur Morris which conclusively establishes that he was boarding with Miss Dally during the Constitutional Convention in 1787.