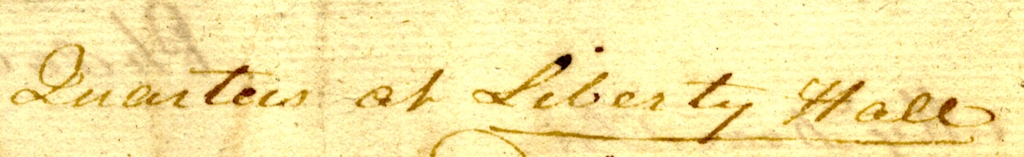

Quarters at Liberty Hall

(Miss Dally Part VIII)

Although history may not repeat, there are times when it rhymes. In such cases history can be prophetic.[1] Miss Dally’s long forgotten boarding house presents a striking example. During the summer of 1787 Gouverneur Morris (the “Penman of the Constitution”) boarded with Miss Dally. A decade earlier Miss Dally’s boarding house was known as “Liberty Hall.” Although additional research is ongoing, history is now ringing with the discovery that Gouverneur Morris boarded at “Liberty Hall” when he “drafted” the Constitution.

Miss Dally’s boarding house comes to life in a remarkable series of letters between New Hampshire Congressional delegate William Whipple and Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee. The “Whipple – Lee correspondence” illustrates the deep friendships that were forged around Miss Dally’s hearth. Massachusetts delegates, including Samuel Adams, began boarding with Miss Dally in 1778 during the Revolutionary War. Members of the founding generation continued boarding with Miss Dally during and after the Constitutional Convention.[2]

Upon his return to Congress in November of 1778, William Whipple wrote to Richard Henry Lee that he had “taken my quarters at Liberty Hall.”[3] This blog post will describe the extraordinary correspondence between Whipple and Lee which demonstrates that Miss Dally’s boarding house was affectionately known as Liberty Hall. Indeed, the evidence suggests that Richard Henry Lee created the label “Liberty Hall” based on the fact that Samuel Adams and the Massachusetts delegation to the Continental Congress were boarding with Miss Dally.

Residents of Liberty Hall

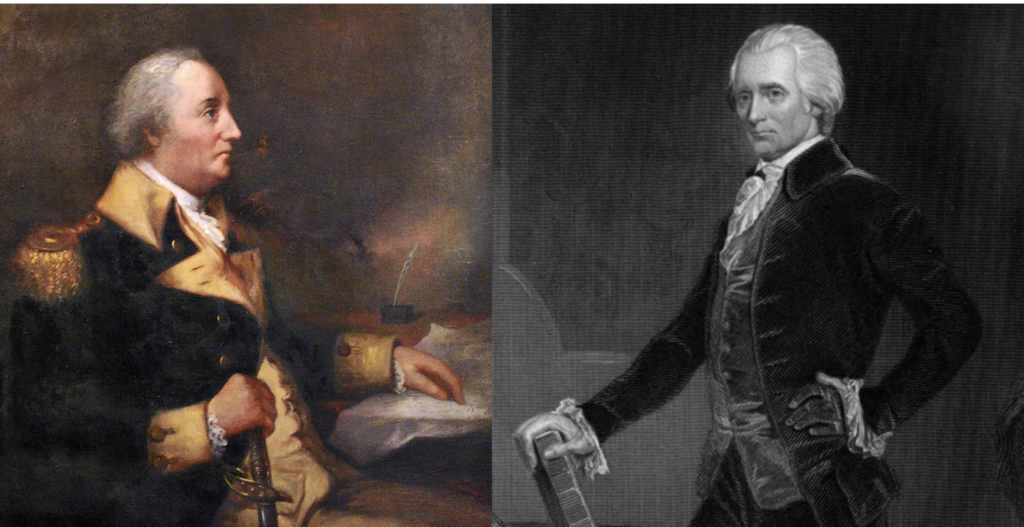

It is likely that William Whipple and Richard Henry Lee first met as delegates to the Second Continental Congress in 1776, a momentous year in American history. Lee represented Virginia at the First Continental Congress beginning in 1774.[4] He became the sixth “President of Congress” in November of 1784.[5] Lee may be best known for the June 1776 “Lee Resolution,” a motion which precipitated the vote to declare independence from Great Britain. Although they shared a similar name, Richard Henry Lee should not be confused with his nephew, Henry Light-Horse Harry Lee.[6] As described by John Adams, in Virginia Richard Henry Lee was considered the “Cicero…of the age,”[7] who was “the first who dared explicitly to propose a Declaration of Independence.”[8]

William Whipple was also a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He represented New Hampshire in the Continental Congress from 1776 to 1779. When he wasn’t on the floor of Congress Whipple was leading troops during the Revolutionary War. Famously, Whipple was a commanding officer during the pivotal Battle of Saratoga in 1777. Whipple was one of two American officers selected to negotiate the terms of General Burgoyne’s surrender. Whipple is pictured in the famous Saratoga surrender scene painted by John Trumbull. Prior to the war Whipple was a prosperous merchant with experience as a ship captain.[9]

During their time together in Congress Whipple and Lee formed a close friendship which is evidenced by years of heartfelt correspondence. While it is reasonable to assume that the term “Liberty Hall” referred to “Independence Hall”[10] in Philadelphia, the Whipple-Lee correspondence discussed below makes clear that Liberty Hall was the “quarters” where Whipple, Lee, Samuel Adams, John Adams and other Massachusetts delegates “spent long winter evenings…with a social pipe and friendly glass.” It made sense that Whipple would board with the Massachusetts delegates as they were all from the same region of the country.[11] Moreover, when Whipple returned to Congress in November of 1778 he was the only New Hampshire delegate in Philadelphia at the time.[12]

Whipple – Lee correspondence

On or about 31 October 1778, Richard Henry Lee departed Philadelphia after having served in Congress since 1774. Prior to leaving, Lee left a letter for William Whipple apologizing that, “I should have been well pleased to have had the pleasure of seeing you here, before my return to Virginia.”[13] In early November Whipple returned to Congress following the stunning victory a year earlier at the Battle of Saratoga. Lee’s letter was delivered to Whipple by Samuel Adams, who was also a boarder at Miss Dally’s.

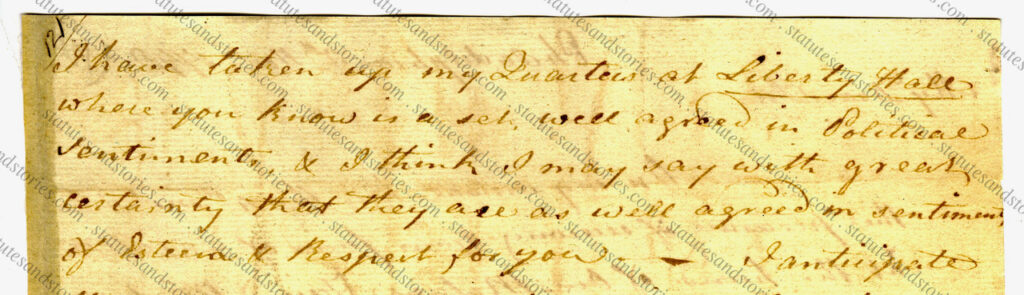

Whipple replied to Lee by letter dated 8 November 1778 indicating that on my arrival I had the pleasure of receiving your letter delivered by “our mutual friend Mr. Adams.” According to Whipple:

I have taken up my quarters at Liberty Hall where you know is a set, well agreed in political sentiments and I think I may say with great certainty that they are well agreed in sentiments of esteem and respect for you. I anticipate the pleasures of some long winter evenings where with a social pipe and friendly glass we shall call to mind our worthy friend and heartily join in wishing he may soon add to our little circle.

The esteem that Lee held for Liberty Hall and the delegates who resided there is evident in his correspondence. In a letter dated November 29, Lee discusses his admiration for the inhabitants of Liberty Hall and the “sociable evenings they pass there.” Writing from his home in Chantilly after his “retirement” to Virginia, Lee expressed his pleasure that the “vessel of state is well steered and likely to be conveyed safely and happily into port.”[14]

Referring to their colleagues from Massachusetts residing at Miss Dally’s, Lee wrote that “[t]hey first taught us to dread the rocks of despotism, and I rest with confidence in their skill in the future operations.” Further confirmation that the Liberty Hall label applied to Miss Dally’s boarding house, Lee’s letter of November 29 provides more details about the venerated quarters of the Massachusetts delegates boarding with Miss Dally.

According to Lee:

I venerate Liberty Hall, and if I could envy its present inhabitants anything it would be the sensible sociable evenings they pass there. I have not yet been able to quit the entertainment of my prattling fireside, when I have when I heard every little story and settled all points, I shall pay a visit to Williamsburg where our Assembly is now sitting.

Lee concludes the November 29th letter by asking Whipple to “[r]emember me with affection to the Society at Liberty Hall, to my friends of Connecticut, R. Island, Jersey, Pennsyln’a & Delaware.” It is clear that by mentioning the “inhabitants” of Liberty Hall, Lee was referring to the quarters where the Massachusetts delegates resided and spent “sociable evenings” with Lee and Whipple. Moreover, the fact that Lee distinguishes between the “Society at Liberty Hall” compared to delegates from other states, is further confirmation that the “inhabitants” at Liberty Hall refers to the Massachusetts delegation residing with Miss Dally.

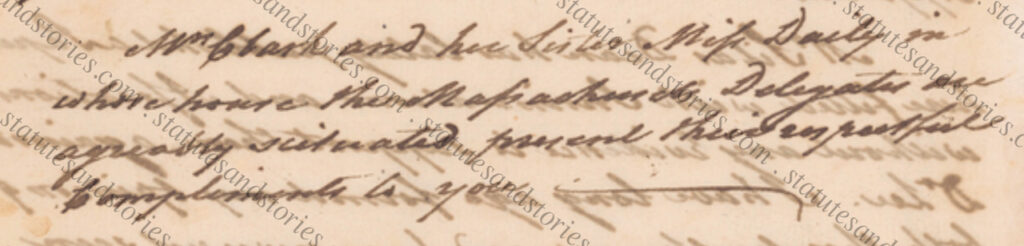

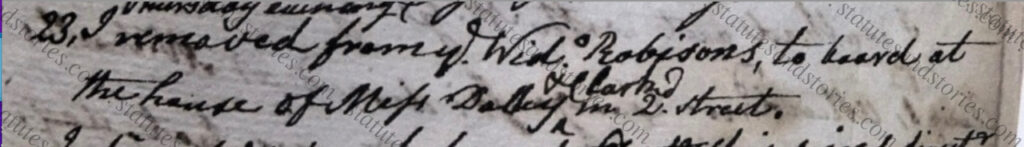

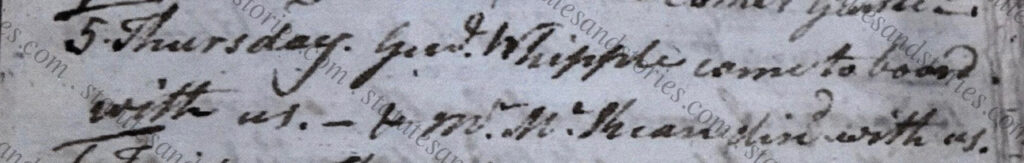

In a letter dated 13 December 1778, Samuel Adams wrote to his wife Betsy indicating that “Mrs Clark and her sister Miss Daily in whose house the Massachusetts delegates are agreeably situated present their respectful complements to you.” According to Massachusetts delegate Samuel Holten, he began boarding with “Miss Dolley & [her sister Mrs.] Clarke” on 23 July 1778, after briefly boarding with the widow Robison. Holten recorded in his diary that “Genl. Whipple came to board with us” on 5 November 1778. [15]

In November of 1778 Samuel Adams shared Lee’s confidence. Although General Howe had taken Philadelphia with 15,000 troops in September of 1777, the British withdrew in June 1778 after occupying the city for nine months. Congress was able to return to Philadelphia in July. No doubt spirits were also buoyed by the fact that earlier in the year the newly independent American nation entered into a formal alliance with France.[16]

In a letter dated November 9, Samuel Adams wrote to James Warren in Boston indicating that “[w]e now begin to hope for peace soon on our own terms….” Adams also reported that “General Whipple is again returned to Congress.”[17] For Adams, Whipple was “a man of sense and great experience in marine affairs” who had served on the Marine Committee. Adams expressed the hope that Whipple could act as the committee chair during Lee’s return to Virginia.

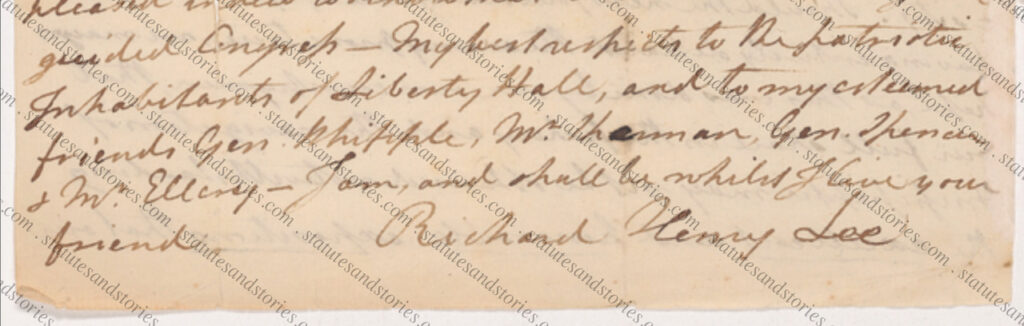

Further confirmation that the term Liberty Hall referred to Miss Dally’s boarding house and the Massachusetts delegates residing there can be found in correspondence between Richard Henry Lee and Samuel Adams and in John Adams’ autobiography. In a letter to Samuel Adams dated 6 June 1779, Lee extended “[m]y best respects to the patriotic inhabitants of Liberty Hall, and to my esteemed friends Gen. Whipple, Mr. Sherman, General Spencer & Mr. Ellery. I am and shall remain whilst I live your friend.”[18]

In his autobiography, John Adams indicates that the title Liberty Hall was conceived by Richard Henry Lee. In September of 1774 when the First Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia, Adams describes how “the Delegates from Massachusetts, representing the state in the most immediate danger,” were frequently visited by members of Congress and other supporters. The Massachusetts delegates initially lodged together “at the Stone House opposite the City Tavern then held by Mrs. Yard which was by some Complimented with the Title of Head Quarters, but by Mr. Richard Henry Lee, more decently called Liberty Hall.” As evidenced by Lee’s subsequent correspondence, he continued using the Liberty Hall designation to refer to any location where the Massachusetts delegation was boarding. In 1778, when the British evacuated Philadelphia, Miss Dally’s boarding house inherited the Liberty Hall title when the Massachusetts delegates returned to Philadelphia and took up residence with Miss Dally.[19]

When describing Samuel Adams, John Adams professed that his cousin had “the most thorough understanding of liberty…as well as the most habitual, radical love of it” was “zealous and keen in the cause” and embodied “steadfast integrity” and “universal good character.”[20] It is thus entirely possible that the association of liberty with Samuel Adams may have been one of the reasons why Richard Henry Lee coined the phrase “Liberty Hall” to describe the quarters where Samuel Adams was living with his Massachusetts colleagues. Similarly, John Adams noted in his diary that Charles Thomson of Pennsylvania was “the Samuel Adams of Philadelphia – the Life of the Cause of Liberty, they say.”[21]

As the war was winding down, Whipple wrote to Lee in April of 1783 to celebrate. Whipple congratulated Lee on the “happy event which for many years has been the great object of your labors and anxious cares. The very unequivocal part you, my dear friend, have taken, in this great revolution, much furnish your hours of retirement with the most pleasing reflections.” Whipple observed that the country was obliged to Lee for his exertions, which helped secure American trade and its fisheries. As a token of this obligation, Whipple enclosed a quintal (100 lbs) of fish.[22]

Lee replied to Whipple on 1 July 1783 indicating that while he enjoyed the fish:

it is also true that I receive it with infinitely more pleasure when it comes as a token of friendship from a gentleman who I shall never cease to respect and esteem, whilst I live. For I am very sure that if my labors in the vineyard of liberty have contributed to the glorious success of our common country, that yours have done none less so – And if the Friendships of the world being too often confedericies in vice or leagues of pleasure, are but short lived; the duration of ours will be as certainly lasting as it is certainly founded on the certain principals of virtuous love for our Country.

After reflecting on their friendship, Lee noted that, “[t]here is no circumstance in life that would make me happier than to see you at Portsmouth and our old Friends in Boston. I hope to do so, if necessary attention to a numerous family (for I have nine children) does not prevent me.”[23]

Postscript: Liberty Trees (and the Boston “Liberty Stump”)

During the Revolutionary War the concept of a liberty was a major theme. The Sons of Liberty would hold meetings under the famous “Liberty Tree” in Boston. The area beneath the “venerable Liberty-Elm” was called “Liberty Hall.” Boston’s beloved Liberty Tree inspired other Liberty Trees across the country. When the British captured Boston in 1775 they made it a point to cut down the Liberty Tree. Thereafter, Bostonians honored their “Liberty Stump.” For this reason when Lafayette visited Boston he paid his respects to the stump. The Provincial Council of Massachusetts used the iconic tree on battle flags.[24]

It should also be noted that the term “Liberty Hall” was not exclusive to Miss Dally’s boarding house when the Massachusetts delegates were boarding with her. For example, William Livingston’s New Jersey home was known as Liberty Hall. Washington and Lee University was founded as Liberty Hall Academy. Yet, history rhymes with the discovery that Gouverneur Morris (and Alexander Hamilton) boarded with Miss Dally at Liberty Hall during the Constitutional Convention. No doubt, “the Penman of the Constitution” was mindful of history when he decided to board with Miss Dally when drafting the Constitution. Perhaps the Liberty Bell was chiming as Morris drafted the Preamble.

Footnotes

[1] According to Mark Twain, “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.” Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World (Doubleday & McClure Co., 1897), 156. Mark Twain attributed the quote to Pudd’nhead Wilson, a fictitious character who Samuel Clemens invented a few years earlier in Pudd’nhead Wilson’s New Calendar.

[2] Gouverneur Morris, Alexander Hamilton and Elbridge Gerry boarded with Miss Dally at various times during the summer of 1787. Gerry initially began boarding with Miss Dally years earlier as a delegate to the Continental and Confederation Congress. Gerry served at various times from 1776-1780 and 1783-1785. Ronald M. Gephart & Paul H. Smith, eds., 26 Letters of Delegates to Congress (2000), xviii.

[3] William Whipple to Richard Henry Lee, 8 November 1778, Letters of Delegates to Congress, ed. Paul H. Smith (1985), 11:187

[4] Other famous delegates to the First Continental Congress included Samuel Adams and John Adams from Massachusetts and George Washington, Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee from Virginia. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774, ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. (1904), 1:14.

[5] Lee served in the Continental Congress prior to, during and after the Revolutionary War: 1774-1779, 1784-1785, 1787. While Lee unsuccessfully opposed ratification of the Constitution in 1788 without amendments, he was elected as one of Virginia’s first senators. In the First Congress he championed the adoption of the Bill of Rights.

[6] Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee earned his nickname during the Revolutionary War as a daring officer in command of light cavalry. He penned the famous phrase “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen” to describe George Washington.

[7] According to John Adams’ diary, the Virginians “speak in raptures about Richard Henry Lee and Patrick Henry – one the Cicero and the other the Demosthenes of the age.” The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, 28 August 1774, vol. 2, 1771–1781, ed. L. H. Butterfield (1961), 113–114.

[8] John Adams to Mercy Otis Warren, 17 August 1807.

[9] Whipple’s maternal grandfather was a prominent shipbuilder. Both Whipple and his father worked as ship captains and became successful merchants in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

[10] At the time, Independence Hall was known as the Pennsylvania State House. The name Independence Hall was derived from “the Hall of Independence” which gradually gained currency beginning in 1824 when the Marquis de Lafayette visited the United and toured Philadelphia, The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, Independence Hall, Charles Mires (2012).

[11] While today New Hampshire is characterized as a “northern” state in New England, Lee referred to Massachusetts and New Hampshire as “eastern states,” as they were east of Virginia.

[12] New Hampshire’s other delegate to Congress, Josiah Bartlett departed Congress on November 3, the day before Whipple arrived on November 4, 1778. William Whipple to Meshech Weare (New Hampshire’s first governor), 24 November 1778, Letters of Delegates, 11:257.

[13] Letters of Delegates, 11:151 & 26:xxii.

[14] The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, ed. James Curtis Ballagh (1914), II:453.

[15] In a diary entry on 5 November 1778, Massachusetts delegate Samuel Holten recorded that “Genl. Whipple came to board with us.” Letters of Delegates, 11:182. According to Holten’s diary he began boarding with “Miss Dolley & [her sister Mrs.] Clarke” on 23 July 1778, after briefly boarding with the widow Robison. Letters of Delegates, 10:344. In a letter dated 13 December 1778, Samuel Adams wrote to his wife Betsy indicating that “Mrs Clark and her sister Miss Daily in whose house the Massachusetts delegates are agreeably situated present their respectful complements to you.”

[16] The British captured Philadelphia after Washington’s defeat at Brandywine and the Battle of the Clouds. The Continental Army wintered at Valley Forge. The Treaty of Alliance and a separate Treaty of Amity and Commerce were signed on 6 February 1778, having been negotiated by American commissioners Ben Franklin, Arthur Lee and Silas Deane. Office of the Historian, French Alliance, French Assistance, and European Diplomacy during the American Revolution, 1778-1782.

[17] Letters of Delegates, 11:189.

[18] The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, ed. James Curtis Ballagh (1914), II:59.

[19] The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 3, Diary, 1782-1804;Autobiography, Part One to October 1776, ed. L. H. Butterfield (1961), 307–313.

[20] The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 1, 1755–1770, ed. L. H. Butterfield (1961), 263–282.

[21] The Adams Papers, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, vol. 2, 1771–1781, ed. L. H. Butterfield (1961), 115-117.

[22] Whipple to Lee, 17 April 1783, Memoir of the Life of Richard Henry Lee, and His Correspondence, grandson Richard H. Lee (1825), 1:238.

[23] The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, ed. James Curtis Ballagh (1914), 2:283.

[24] According to historian David Hackett Fischer, while many cultures have honored trees, “Boston was unique for its reverence for a shattered stump, which became a double symbol of American rights and British tyranny.” Liberty and Freedom: A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas (2005), 23-30.