Why did Alexander Hamilton leave the Constitutional Convention?

“The Penman-Publius Axis” – Part 1

It is generally understood that “[t]he Constitutional Convention was Hamilton’s child. No one had wanted it more than he did, or had fought for it so long.”[1] His biographers emphasize that when he arrived in Philadelphia nobody had a “better right to be there” than Hamilton.[2] If so, why would he purportedly flee[3] the Convention during the summer of 1787 ?

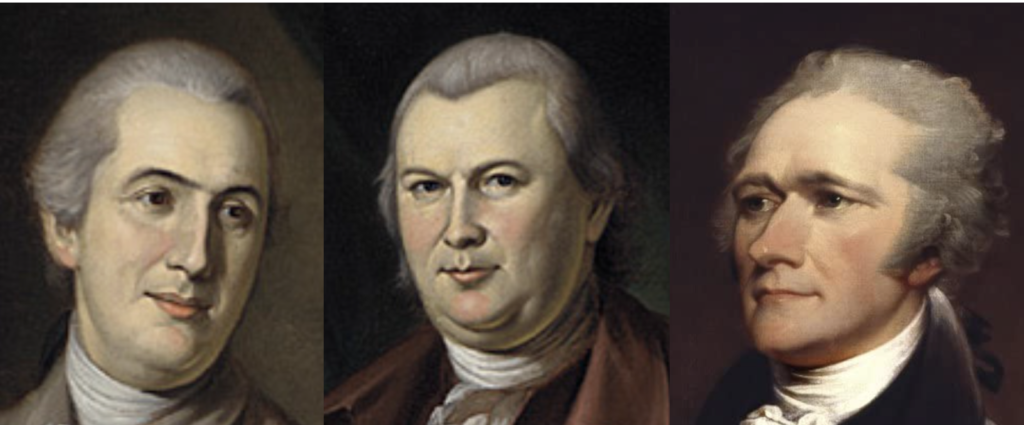

During the Revolutionary War Alexander Hamilton was one of the first to publicly propose a Constitutional Convention. Years ahead of his time, Hamilton recognized and diagnosed the defects with the Articles of Confederation. He then played an instrumental role in calling for the Philadelphia Convention, which finally convened in May of 1787. Yet, Hamilton prematurely departed the Convention on June 30. Although he subsequently returned, why did he leave in the first place? Hamilton famously became the only New York delegate to sign the Constitution on September 17. But what would have motivated one of the most ardent champions of Constitutional reform to be absent from Philadelphia during critical debates in July and August?

Historians invariably explain that Hamilton was “frustrated”[4] when he left the Convention on June 30. Some focus on the fact that it was frustrating for Hamilton that he was consistently undermined by his co-delegates from New York who repeatedly voted against him. Other historians emphasize that Hamilton was frustrated by the lack of support for his five-hour speech on June 18. While the lack of support for Hamilton’s proposals may have been disappointing, was mere frustration in fact the reason for Hamilton’s departure? Hamilton admitted that he feared that a “golden opportunity of rescuing America” was slipping away.[5] So why did he leave?

According to the traditional narrative Hamilton was in “a hopeless position” within his delegation.[6] “When it came to being impatient and impetuous, Hamilton had few peers.”[7] At the time he departed he “no longer felt his presence useful, and the strains had become too great for him to bear.”[8] “His departure was prompted by a combination of hurt feelings over the cool reception to his June 18 speech” along with “the realization that he was doomed to be outvoted on any important question by his two antinationalist New York colleagues.”[9] Hamilton was “frustrated and restless”[10] when he left, “more in sorrow than anger.”[11] Or was the reason for his departure that he “overwhelmed with a sense of alienation”?[12] While the conventional wisdom may accurately describe Hamilton’s dilemma at the Convention as a “minority delegate from a dissenting state,”[13] the notion that he voluntarily decided to leave out of frustration is inconsistent with Hamilton’s own explanation for his departure.

During the New York Ratification Convention in 1788 Hamilton explained that “private business” called him back to New York.[14] In a letter to George Washington shortly after his departure, Hamilton explained that “I shall of necessity” remain in New York “ten or twelve days.”[15] Nevertheless, historians have been unable to identify what pressing matters would have justified Hamilton’s departure.[16]

New evidence has come to light about the circumstances surrounding Hamilton’s return to New York. As far as can be determined, no historian has advanced the explanation described below. This post is divided into two parts. Part I: The Hamilton-Morris Axis introduces the hypothesis that Hamilton departed Philadelphia in response to breaking news from London of a credit crisis implicating Robert Morris’ financial empire. Who better than Alexander Hamilton to help address this financial crisis?

Within a few months Hamilton would assume the pseudonym Publius and Gouverneur Morris would be selected as the “penman of the Constitution.” Hence, the label “Penman-Publius Axis” for Part 1 is appropriate to describe the growing evidence of collaboration between Hamilton and Morris, who were close friends and colleagues for decades. Of course, Hamilton had been appointed by Robert Morris as the Receiver of Continental Taxes for the State of New York in 1782. As one of the founders of the Bank of New York, Hamilton was well-versed in this subject.

Hamilton was not the only delegate with underwhelming attendance at the Convention. For example, on May 30 Gouverneur Morris departed the Convention after only six days. Until recently, historians have incorrectly assumed that Morris returned to the Convention on July 2, after spending a month attending to his recently purchased Morrisania estate. Part 1 argues that this traditional explanation is flawed.

A newly uncovered invoice changes our understanding of Gouverneur Morris’ Convention timeline. According to the invoice, Gouverneur Morris arrived in Philadelphia on June 30, the same day that Hamilton departed for New York. In other words, the Penman-Publius Axis theorizes that Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris were closely collaborating to avert a bank run involving former Superintendent of Finance, Robert Morris.

Part 2: Unanswered Research Questions acknowledges that we are working from an incomplete historic record. Hamilton’s correspondence files – legal and personal – are admittedly and unfortunately sparse during this critical period. For this reason it is useful to sketch out further research questions to be pursued to help prove the merits of the Penman-Publius Axis as a tool to understand Hamilton’s June 30th departure from the Convention.

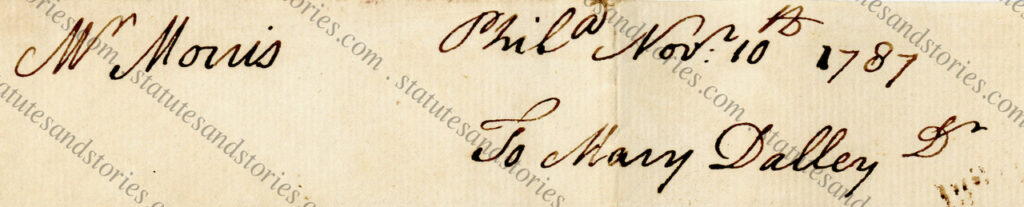

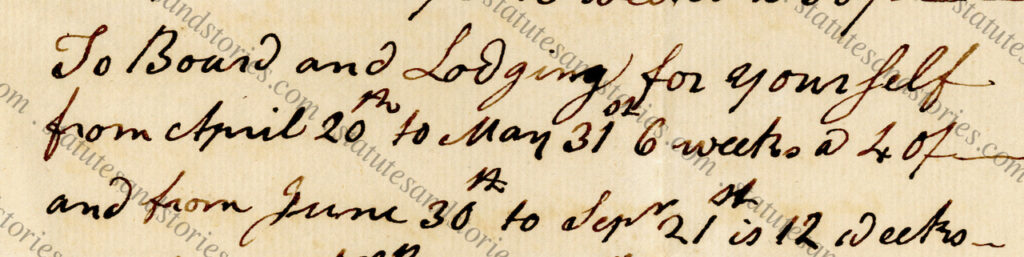

Gouverneur Morris’ newly uncovered receipt from Miss Dalley

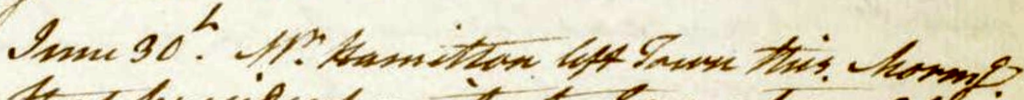

Earlier this year, a seemingly mundane receipt was uncovered in Philadelphia. This single slip of paper has the potential to reshape our understanding of key moments at the Constitutional Convention. Pictured below is Miss Dalley’s receipt to Gouverneur Morris for “board and lodging” during the Constitutional Convention. Click here for a discussion of other newly discovered evidence of Hamilton’ s arrival at the Convention earlier than previously understood.

Importantly, the receipt is clear that Morris was charged by Miss Dalley for room and board through May 31. After he returned to Philadelphia from New York, charges began accruing again on June 30. This June 30 date is significant for several reasons.

For decades, historians have assumed that Morris returned to Philadelphia on July 2, not June 30. Given incomplete information, this was a safe assumption as Morris’ name reappears in Madison’s Convention notes beginning on July 2. Indeed, Max Farrand concluded that Gouverneur Morris “was absent until July 2.”

So why would two days on a timeline make a difference? The answer is that Gouverneur Morris’ June 30 return to Philadelphia precisely aligns with evidence that Hamilton departed Philadelphia on June 30. The Penman-Publius Nexus argues that this is not a mere coincidence. In particular, stunning news had just recently arrived in Philadelphia that Robert Morris’ financial operations were hanging in the balance, with dire implications for the already precarious credit of the United States.

Protested Accounts in London

For many years Robert Morris had been the nation’s wealthiest and most influential merchant financier. Robert Morris played an indispensable role financing the Continental army during the Revolutionary War. For good reason he was selected as the first Superintendent of Finance under the Confederation Congress. After the Constitution was ratified, George Washington asked Morris to become the first Treasury Secretary, but Morris recommended Hamilton instead.

Morris’ far-flung global operations included shipping operations in China and affiliates in London and Paris. Morris’ partner in New York was William Constable, who extended credit across the Atlantic through their colleague John Rucker in London.

On May 7, John Adams, the American minister in London, learned that Robert Morris’ bills were being protested (the equivalent of bouncing checks). According to Adams, “[t]his catastrophe has shocked me, and will be a great disappointment to the Board of Treasury…”

A day later Adams wrote to the Board of Treasury in Congress explaining that “there is a great alarm in London and the consequences cannot be forseen…” Adams’ May 8 letter explained that “I was much hurt for Mr. Rucker and his Family, for the private Credit of American Merchants, and for the public Credit of the United States: but the Evil was without a Remedy.”

The alarming news of Morris’ distressed credit reverberated across political and diplomatic circles. On May 10 Abigail Adams described “an event which has spread an amazing alarm here within a few Days. I mean the protesting . . . of Mr. Morris & Co bills.” As noted by Abigail, this was “a terrible stab to what little remained of credit to America.” Fully understanding the implications of a bank run, Abigail worried, “as to his other Bills being protested, the whole city rings with it, and I suppose in consequence of it every House with which he is concerned will push him at once.”

The news of the pending “disaster” reached Thomas Jefferson in Paris on May 21. As described to Jefferson, “a late occurrence has very much alarmed every wellwisher.” Namely, Morris’ bills were being protested after Morris’ agent in London, Mr. Rucker, was unable to make payments and had abruptly returned to New York.

On May 23, Adams wrote to John Jay indicating that he was leaving for Holland to obtain alternate financing for American loan payments. Enclosing copies of the protested debts, Adams feared that Morris’ default threatened the “immediate and total ruin to the credit of the United States.”

Timing of Hamilton’s departure and Gouverneur Morris’ return from New York

The fact that Morris’ partner in London, John Rucker, had unexpectedly picked up and left for New York is not by itself proof of the reason why Alexander Hamilton departed the Convention on June 30. Admittedly, there is no direct evidence that Hamilton conferred with Morris or had any ability to assist. Yet, the timing of Hamilton’s departure for New York is significant, coupled with the date of the arrival of this news in Philadelphia.

During the Constitutional Convention, George Washington boarded with Robert Morris. He had planned on boarding with James Madison and other Virginian delegates at Miss Mary House’s boarding house, but Morris prevailed upon him to reside at the Morris mansion. On June 28, George Washington recorded in his diary that he was dining in a large company at Morris’ house when “the news of his bills being protested” became public. Washington also notes that the news arrived “last night” and apparently was “mal-apropos” for discussion during a dinner party.

The following picture emerges as several data points come together:

- news of Morris’ financial distress arrives in Philadelphia on the evening of June 27

- the news becomes public on June 28

- Hamilton departs the Convention on the morning of June 30

- Gouverneur Morris, Robert Morris’ lawyer, remains in Philadelphia because he had just returned from New York that same day.

For decades, historians have repeatedly offered two reasons for why Gouverneur Morris left the Convention at the end of May thereby missing the entire month of June. In 2005, Gouverneur Morris biographer James J. Kirschke[17] summarized that Morris left Philadelphia “primarily to make the final financial arrangements to take title of the Morrisania estate” that he had recently purchased. Among other things, Morris needed to train the new overseer, lay out plans for new construction, planting, and his laborers. Morris recognized that the “fate of America was suspended by a hair.” Yet, Kirschke concedes that Morris chose to prioritize “personal business over the nation’s formative process.”

Biographer Max Mintz explains that Morris took his one-month leave from the Convention “to attend to the affairs of his Morrisania estate.” After having hired an overseer and a large number of laborers, “Morris needed to lay out work for them.” Thus, Mintz too believed that Morris’ hiatus was based on “extensive building” in Morrisania along with the need for “tree and crop planting.”[18]

Is it possible that the domestic plans for his new Morrisania estate were not the only (or primary) reason why Morris left the Convention on May 31? Richard Brookhiser’s 2003 biography of Gouverneur Morris hints at another explanation:

A new estate manager at Morrisania required instructions, and one of William Constable’s agents had arrived in New York from Europe with the news that their partner Robert Morris’s bills were being protested (in effect, his checks were bouncing). America might be hanging by a hair, but Gouverneur Morris spent all of June tending to these matters.[19]

While Brookhiser does not specifically footnote his claim, he did not have access to Miss Dalley’s receipt. Of course, it is possible that both Robert Morris and Gouverneur Morris had advance knowledge of the pending financial difficulties, which would provide a better explanation for Gouverneur’s priorities in June. Thus, the Morrises would not have known when Rucker would be departing London and setting off alarms in European capitals, but they may have seen the writing on the wall.

A similar argument was made by Robert Morris biographer, Charles Rappley, who also didn’t have access to Miss Dalley’s receipt. Importantly, Rappley’s proposed chronology is meaningfully different from Brookhiser’s. Rappley writes that there was no containing of the damage of the “tangled affairs Rucker had left behind in London.” According to Rappley’s 2010 biography:

It was a huge setback for Morris and his partners, serious enough that Gouverneur Morris had to leave the federal convention to spend two weeks in New York conferring with Constable.[20]

Rappley would be incorrect to suggest that Gouverneur Morris left Philadelphia at the end of May based on the news of Rucker’s arrival. Nonetheless, it remains to be seen whether Gouverneur Morris and Robert Morris were reading the tea leaves preparing for the inevitable news that arrived in Philadelphia on the night of June 27.

In 1787 it took approximately six weeks for a ship to sail across the Atlantic, depending on the weather, the direction of travel and other variables. Knowing that Rucker began protesting Robert Morris’ bills in early May, it makes sense that the alarming news arrived in Philadelphia in late June, approximately two months later.

This post will be continued in Part 2: Unanswered Research Questions (pending), which will examine what we know and don’t know about the “The Penman-Publius Axis” as an explanation for Hamilton’s departure from the Convention on June 30 and Morris’ absence in the month of June.

Footnotes

[1] Noemie Emery, Alexander Hamilton: An Intimate Portrait (1982), 92.

[2] Clinton Rossiter, Alexander Hamilton and the Constitution (1964), 42. “Only Madison did as much at the right moments to bring this event to fruition, and he must have been stiffened more than once in his own nationalism, and encouraged to fight on….by the example of his gallant friend from New York.”

[3] Marie B. Hecht, Odd Destiny: The Life of Alexander Hamilton (1980), 127.

[4] Hamilton biographer John C. Miller indicates that Hamilton was “frustrated at every turn,” and left, “unhappily, strife torn.” Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox (1959), 176. For Clinton Rossiter, Hamilton left “out of frustration over the pig headedness of his fellow delegates from New York.” 1787: The Grand Convention (1966), 165. John P. Kaminski writes that Hamilton left the Convention, “totally frustrated with his minority position within the New York delegation.” George Clinton: Yeoman Politician of the New Republic (1993), 120. Carol Berkin agrees that “the frustrating composition of the New York delegation had driven him away from Philadelphia.” Berkin further suggests that “it was humiliating for a man accustomed to dominate to be reduced to impotence by the likes of Yates and Lansing.” A Brilliant Solution: Inventing the American Constitution (2002), 119. According to Michael Meyerson, Hamilton’s departed after growing “impatient with prolonged debate” and frustrated with the direction the Convention was taking. Liberty’s Blueprint (2008), 71.

[5] Three days after he left the Convention for New York, Hamilton wrote to Washington that, “I own to you Sir that I am seriously and deeply distressed at the aspect of the Councils which prevailed when I left Philadelphia. I fear that we shall let slip the golden opportunity of rescuing the American empire from disunion anarchy and misery.”

Hamilton to Washington, 3 July 1787.

[6] David Stewart, Madison’s Gift: Five Partnerships that Built America (2015), 33.

[7] Stewart, 23.

[8] Noemie Emery, Alexander Hamilton: An Intimate Portrait (1982), 101.

[9] Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men (2009), 202.

[10] Ray Raphael, Mr. President: How and Why the Founders Created a Chief Executive (2012), 76.

[11] Charles A. Cerami, Young Patriots: The Remarkable Story of Two Men, Their Impossible Plan, and the Revolution that Created the Constitution (2005), 166.

[12] Marie B. Hecht, Odd Destiny: The Life of Alexander Hamilton (1980), 127-128.

[13] Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (2004), 227.

[14] DHRC, 22:1808.

[15] Hamilton to Washington, 3 July 1787.

[16] As far as can be determined, when he returned to New York Hamilton worked on several cases concerning business disputes. He also attended the circuit court in Albany, but “little of it” was pressing and “none urgent enough to justify his absence from the convention he had worked seven years to bring about.’ Emery, 102.

[17] James J. Kirschle, Gouverneur Morris: Author, Statesman, and Man of the World (2005), 167.

[18] Max M. Mintz, Gouverneur Morris and the American Revolution (1980), 185.

[19] Richard Brookhiser, Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris – The Rake Who Wrote the Constitution (2003), 81.

[20] Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution (2010), 437.