The History of Jury Unanimity

Why do “The Twelve Angry Jurors” need to be unanimous?

A frequently asked question by jurors (and the audience and cast of the play Twelve Angry Jurors) is why do juries have to be unanimous? The answer is more complicated than you might think. Although the right to a jury trial is expressly protected by the Constitution, the word “unanimous” does not appear in the Constitution’s text. So what is the basis of the famous unanimity requirement?

There can be no doubt (reasonable or otherwise) that the right to a jury trial is sacrosanct under the American criminal justice system. Yet, the right to a unanimous jury is a more complex issue. Indeed, the United States Supreme Court only recently resolved this question in the year 2020. In the non-unanimous case of Ramos v. Louisana the Court held that it was unconstitutional for Louisiana and Oregon to allow felony convictions by 10-2 jury verdicts. [1]

History of the Right to Jury Trial

In order to understand the unanimity requirement, it is useful to begin with a review of the underlying right to a jury trial. As described by John Adams, representative government and the right to trial by jury were the heart and lungs of liberty. Without these rights, Adams explained, the people have “no other security against being ridden like horses, fleeced like sheep, worked like cattle, and fed and clothed like swine and hounds.” [2] When drafting the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson cited deprivation of the “benefits of trial by jury” in the list of grievances against King George III.

Jefferson was referring to the Intolerable Acts adopted by Britain in 1774 following the Boston Tea Party. In particular, the punitive “Massachusettes Government Act” limited the use of colonial juries, restricted who could serve on juries and gave royal judges control over jury selection. As described in 1961 by Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, impairment of the right to trial by jury and denial of related legal protections “led, first, to the colonization of this country, later, to the war that won its independence, and, finally, to the Bill of Rights.” [3]

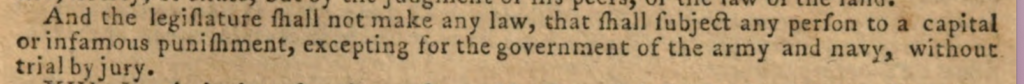

After America declared independence from England, each of the thirteen states recognized the importance of the right to trial by jury. For example, the Massachusetts Constitution required “trial by jury,” but did not specify a particular jury procedure. Written by John Adams in 1780, the Massachusetts Constitution is the oldest constitution in the world in continuous operation. Part 1, Article XII, of the Massachusetts Constitution provides as follows and is pictured below:

And no subject shall be arrested, imprisoned, despoiled, or deprived of his property, immunities, or privileges, put out of the protection of the law, exiled, deprived of his life, liberty, or estate, but by the judgment of his peers, or the law of the land. And the legislature shall not make any law, that shall subject any person to a capital or infamous punishment, excepting for the government of the army and navy, without trial by jury.

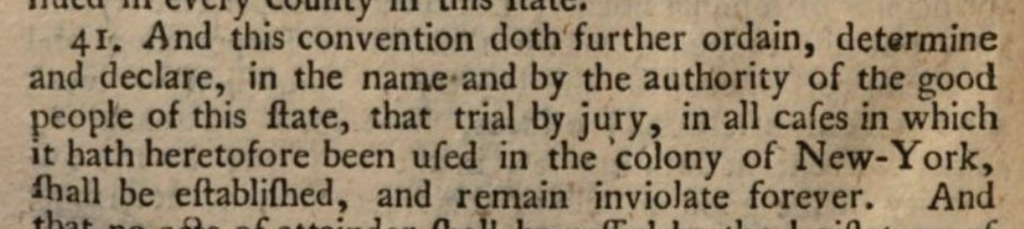

The New York Constitution adopted in 1777 similarly requires “trial by jury,” but is silent on the issue of jury unanimity. More detailed than the Massachusetts provision pictured above, Section 41 of the New York Constitution provided that the right to trial by jury would apply “in all cases in which it hath heretofore been used in the colony of New-York” and shall remain inviolate forever. Importantly, Section 35 of the New York Constitution also provided that the Common Law of England in 1775 shall remain “the law of this state.” It is through this mechanism, the Common Law of England, that jury unanimity becomes a constitutional requirement in America.

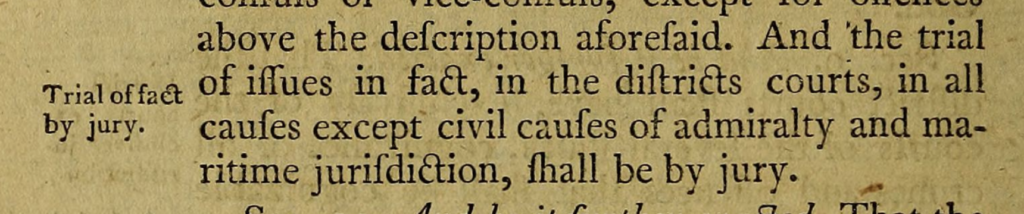

In addition to being protected by each of the original thirteen states, the right to trial by jury was also recognized by the First Congress. The Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the federal courts, was written prior to the Bill of Rights. Section 9 of the Judiciary Act provides that the trial of issues of fact in the federal district courts “shall be by jury.”

The Constitution and the Bill of Rights

The right to trial by jury is one of the few rights specifically mentioned in the body of the Constitution (Article III, Section 2). The 6th Amendment (criminal cases) and 7th Amendment (civil cases) further expand on the right to jury trial. So why did the Supreme Court wait over 230 years to finally conclude that criminal defendants have the right to a unanimous jury verdict? The quick answer is that when originally drafted in 1789 by James Madison and the First Congress, the Bill of Rights only applied to the states.

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution provides that, “[t]he trial for all crimes shall be by jury and such trial shall be held in the state where the said crimes have been committed.” The Sixth Amendment further elaborates that “[i]n all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed.” The Seventh Amendment addresses the right to jury trial in civil cases.

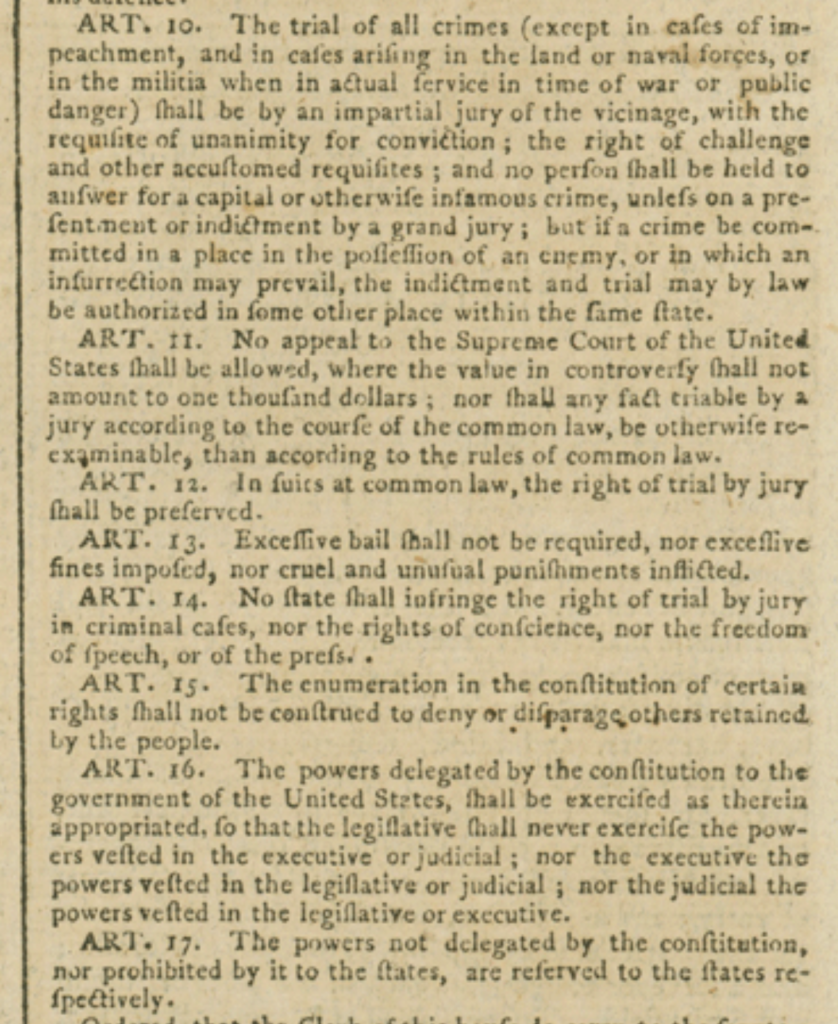

Pictured below is James Madison’s initial draft of the Bill of Rights introduced in the House of Representatives on June 8, 1789. [4] As envisioned by Madison, the proposed 10th Amendment would have afforded the right to an “impartial jury of the vicinage, with the requisite of unanimity for conviction.” You will note that Madison’s list contained seventeen proposed amendments. The Senate would revise and consolidate Madison’s list down to twelve amendments. Ultimately, the states only ratified ten of the twelve proposed amendments in December of 1791.

Over time the Supreme Court gradually held that most of the protections of the Bill of Rights were applicable to the states. According to the Court, the projections in the Bill of Rights were extended to the states through the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment. The process by which states were required to comply with the Bill of Rights is known as the selective “incorporation” doctrine. After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment required that “No state shall…deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law….” In other words, if a right in the Bill of Rights was essential to due process, the states were prohibited from violating that right.

As described in the Ramos case by Justice Gorsuch, the requirement of juror unanimity dates back under English Common Law to the 14th Century:

As Blackstone explained, no person could be found guilty of a serious crime unless “the truth of every accusation . . . should . . . be confirmed by the unanimous suffrage of twelve of his equals and neighbors, indifferently chosen, and superior to all suspicion.” A “ ‘verdict, taken from eleven, was no verdict’ ” at all.

The Ramos court also surveyed the history of the legal system in America. The court concluded that consistent with the English Common Law, American courts “appeared to regard unanimity to be an essential feature of the jury trial.” In a 6-3 decision, Ramos held that the 6th Amendment right to jury unanimity, as incorporated against the states through the 14th Amendment, “is fundamental to the American scheme of justice.”

[1]. Ramos v. Louisiana, 590 U.S. ___ (2020).

[2]. This quote appears in Adams’ diary and in a newspaper essay he wrote under the pseudonym Claredon.

[3] Cohen v. Hurley, 366 U.S. 117, 140 (1961) (Black, dissenting).

[4] After debating Madison’s proposal during the summer, on August 24, 1789 the House of Representatives approved a draft with seventeen proposed Amendments. On September 9 the Senate altered but approved twelve of the seventeen proposed amendments. Click here for a link to the Senate revisions to the House version. Articles three through twelve were ratified on December 15, 1791 and are now known as the Bill of Rights.