Melancton Smith’s Fingerprints

The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” (Part 3)

Adam P. Levinson, Esq. & John P. Kaminski, PhD

During his first speech at the New York ratification convention Melancton Smith delivered a damning criticism of slavery and the proposed Constitution. Refusing to pull any punches, Smith described slavery as “utterly repugnant.” He observed that the rule of apportionment governing the House of Representatives was “absurd,” founded on “unjust principles,” and the result of an accommodation “with the southern states.” Calling out those who benefitted from the Three-Fifths compromise, Smith declared that “the very operation of it was to give certain privileges to those people who were so wicked as to keep slaves.”[1]

The same bold, outspoken criticism of slavery appeared seven months earlier in Brutus III. Addressing the same rule of apportionment, Brutus sarcastically observed: “What a strange and unnecessary accumulation of words are here used to conceal from the public eye” what might have been more concisely stated. Brutus quoted Montesquieu for the proposition that “in a free state” the legislature should reside in the whole body of the people. Why Brutus asked should slaves, “who are not free agents” and have “no share in government” be included in the representation formula? Brutus derisively answered:

Is it because in some of the states, a considerable part of the property of the inhabitants consists in a number of their fellow men, who are held in bondage, in defiance of every idea of benevolence, justice, and religion, and contrary to all the principles of liberty, which have been publickly avowed in the late glorious revolution?

Next, Brutus proceeded to lay bare the illogic of the clause:

If this be a just ground for representation, the horses in some of the states, and the oxen in others, ought to be represented—for a great share of property in some of them, consists in these animals; and they have as much controul over their own actions, as these poor unhappy creatures, who are intended to be described in the above recited clause, by the words, “all other persons.”

Finally, Brutus condemned the inhumanity and hypocrisy of slavery and the slave trade:

What adds to the evil is, that these states are to be permitted to continue the inhuman traffic of importing slaves, until the year 1808—and for every cargo of these unhappy people, which unfeeling, unprincipled, barbarous, and avaricious wretches, may tear from their country, friends and tender connections, and bring into those states, they are to be rewarded by having an increase of members in the general assembly.[2]

These were not hollow words for Melancton Smith. When he delivered his convention speech of 20 June 1788 decrying slavery, Smith was “very likely the most actively anti-slavery man in the entire Congress.”[3] Smith was a founding member of the New York Manumission Society and would continue to be an active opponent of slavery for years to come.[4] Unlike many of the speakers at the New York ratification convention, there is no evidence that Smith ever owned slaves.[5] In fact, all of the other leading Antifederalists who have been suggested as authors of Brutus were slaveowners.[6] Accordingly, Smith’s consistent and profound opposition to slavery is compelling attribution evidence that helps confirm the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.”[7]

Overview of Brutus Attribution

This blog post is the third of a multi-part series exploring the authorship of the sixteen letters of Brutus. The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” argues that Brutus was Melancton Smith, Alexander Hamilton’s chief opponent at the New York ratification convention in Poughkeepsie. Part 1 provides an overview of existing scholarship and a summary of the new evidence compiled by Statutesandstories.com in collaboration with John P. Kaminski. Part 2 and 3 set forth the detailed attribution evidence summarized in Part 1.

Part 2 focused on pre-authorship attribution evidence arising prior to the printing of the Brutus essays from 18 October 1787 to 10 April 1788. Part 3 continues with a discussion of post-authorship attribution evidence primarily arising from Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention.[8] Part 4 will present the remaining categories of attribution evidence, with a focus on Smith’s syllogistical reasoning style. Part 5 (pending) will discuss newly uncovered speeches by Melancton Smith which further confirm Melancton Smith’s identity as Brutus.

The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” is based on a detailed review of decades of correspondence, pamphlets, legislative history, records of the New York ratification convention, and recently uncovered speeches by Smith. Much of this work is only made possible after the completion of the monumental forty-seven volumes of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (DHRC). Readers are advised that Parts 2 and 3 are not intended to be a quick read. Unlike more traditional and reader friendly blog posts, Parts 2 and 3 might best be consumed in digestible installments.

Earlier this year, Statutesandstories released a related seven-part series about the Antifederalist Federal Farmer. Historians have long recognized Brutus and the Federal Farmer as the two most important Antifederalist authors. For decades, the Federal Farmer was believed to have been Richard Henry Lee. In 1974, historian Gordon Wood challenged this longstanding attribution, but did not offer a replacement author. In 1988, John P. Kaminski released a paper arguing that Elbridge Gerry was the Federal Farmer. Click here for a link to the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis (“FEAT”) which surveys newly uncovered evidence that Elbridge Gerry was in fact the Federal Farmer. With Elbridge Gerry confirmed as the Federal Farmer, the field is cleared for Melancton Smith to be recognized as Brutus.

Part 2 was organized into the following categories of attribution evidence:

- Smith’s 1784 pamphlet opposing the holding in the case of Rutgers v. Waddington which made Smith a leading early critic of judicial review;

- the choice of the pseudonym Brutus and Smith’s political rivalry with Alexander Hamilton;

- Smith’s speech to Congress defending New York’s conditional adoption of the impost requested by Congress;

- Smith’s two pamphlets as A Republican defending New York’s actions on the impost;

- the nexus and political relationship between Smith and New York Governor George Clinton, as evidenced in Charles Tillinghast’s letter to Hugh Hughes dated 27 January 1788; and

- logistical considerations which place Smith in Brutus’s shoes.

Part 3 continues with a discussion of the following Melancton Smith “fingerprints,” additional attribution evidence which flows in large part from Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention in June and July of 1788:

- Brutus’s frequent use of biblical references which aligns with Smith’s biography as an “ardent Presbyterian” and “pillar of his church”;

- Smith’s ardent and abiding opposition to slavery which aligns with Brutus;

- Smith’s linguistic fingerprints (words and phrases reoccurring in Smith’s correspondence and speeches) which align with Brutus.

Part 4 will present the remaining categories of attribution evidence and fingerprints which connect Smith to Brutus:

- Smith’s logical and syllogistic reasoning style which aligns with Brutus;

- Brutus’s lack of insider knowledge relating to the Constitutional Convention, in contrast to the Federal Farmer;

- Brutus’s intimate knowledge of the workings of the Confederation Congress which aligns with Smith’s service in Congress beginning in 1785.

Brutus’s frequent use of biblical references aligns with Smith

Brutus’s letters are replete with biblical and religious references, as are the pages of Plebeian which is also believed to have been written by Smith. Taken together, Brutus and Plebeian contain over three dozen biblical references, including prayers. As discussed below, this same pattern of frequent biblical allusions occurs in Smith’s correspondence throughout his life. It should thus not be surprising that several of Smith’s convention speeches likewise contain similar biblical references. This is particularly true for Smith’s early convention speeches which are more likely to have been prepared in advance of the convention, compared with later speeches which were more narrowly focused.

The following chart evidences over thirty biblical and/or religious references in Brutus 1-7, 9, 10, 15 & 16, including four biblical references in Brutus 1.

| Biblical References by Brutus | ||

| Brutus 1 | “generations to come will rise up and call you blessed.” | Luke 1:48 |

| Brutus 1 | “The most important question that was ever proposed to your decision, or to the decision of any people under heaven, is before you…” | |

| Brutus 1 | “The territory of the United States is of vast extent; it now contains near three millions of souls” | |

| Brutus 1 | “perfection is not to be expected in any thing that is the production of man” | |

| Brutus 2 | “Law of nature or of God” | |

| Brutus 2 | “If they had been disposed to conform themselves to the rule of immutable righteousness, government would not have been requisite.” | |

| Brutus 3 | “Is it because in some of the states, a considerable part of the property of the inhabitants consists in a number of their fellow men, who are held in bondage, in defiance of every idea of benevolence, justice, and religion, and contrary to all the principles of liberty, which have been publickly avowed in the late glorious revolution?” | |

| Brutus 4 | “As it is true what the Apostle Paul saith, that “no man ever yet hated his own flesh, but nourisheth and cherisheth it.” | Ephesians 5:29 |

| Brutus 4 | “Thus when the prophet Elisha told Hazael, “I know the evil that thou wilt do unto the children of Israel; their strong holds wilt thou set on fire, and their young men, wilt thou slay with the sword, and wilt dash their children, and rip up their women with child.” Hazael had no idea that he ever should be guilty of such horrid cruelty, and said to the prophet. ‘‘Is thy servant a dog that he should do this great thing.” Elisha answered. “The Lord hath shewed me that thou shalt be king of Syria.” The event proved, that Hazael only wanted an opportunity to perpetrate these enormities without restraint, and he had a disposition to do them, though he himself knew it not.” | 2 Kings 8:12–13 |

| Brutus 4 | painted sepulcher | Matthew 23:27 |

| Brutus 4 | “they will then have to wrest from their oppressors, by a strong hand, that which they now possess, and which they may retain if they will exercise but a moderate share of prudence and firmness.” | |

| Brutus 5 | “so oppressive, as to grind the face of the poor” | Isaiah 3:15 |

| Brutus 5 | “and which will introduce such an infinite number of laws and ordinances, fines and penalties. courts, and judges. collectors, and excisemen, that when a man can number them, he may enumerate the stars of Heaven.” | |

| Brutus 6 | “Contradicts the scripture maxim: which saith: no man can serve two masters’ ” | Matthew 6:24 |

| Brutus 6 | “it will be a constant companion” | |

| Brutus 6 | “…..even at church” | |

| Brutus 6 | “light upon the head of every person” | Job 29:3 |

| Brutus 6 | “immutable laws of G-d and reason” | |

| Brutus 6 | “unless the people rise up, and, with a strong hand, resist and prevent the execution of constitutional laws” | |

| Brutus 7 | “matter of mere grace and favor” | |

| Brutus 7 | ‘Let the monarchs in Europe, share among them the glory of depopulating countries, and butchering thousands of their innocent citizens, to revenge private quarrels, or to punish an insult offered to a wife, a mistress, or a favorite: I envy them not the honor, and I pray heaven this country may never be ambitious of it.” | |

| Brutus 9 | “making the Alcoran a rule of faith” | |

| Brutus 9 | “the establishment of the Mahometan religion” | |

| Brutus 10 | “What the consequences of such a determination would have been, heaven only knows….as it ever did in any country under heaven.” | |

| Brutus 15 | “and which indeed transcends any power before given to a judicial by any free government under heaven.” | |

| Brutus 15 | “There is no authority that can remove them, and they cannot be controuled by the laws of the legislature. In short, they are independent of the people, of the legislature, and of every power under heaven. Men placed in this situation will generally soon feel themselves independent of heaven itself.” | |

| Brutus 15 | “required the spirit of a martyr” | |

| Brutus 15 | “without the spirit of prophecy” | |

| Brutus 15 | “any free government under heaven; every power under heaven; independent of heaven itself” | |

| Brutus 15 | “High hand and an outstretched arm” | Deuteronomy 26:8 |

| Brutus 16 | “…forget the hand that formed them” | Paradise Lost by John Milton – quoting devil |

It is noteworthy that Brutus’s biblical lens is in stark contrast with the letters of the Federal Farmer (Elbridge Gerry), which contain only a single passing reference to “the days of Adam.” This dichotomy between Brutus and the Federal Farmer has been noted by historians for decades. According to David E. Narrett, “[t]he more plainspoken Smith quoted from the Bible, a practice fairly common in Brutus but not in the Federal Farmer.” By contrast, the “Federal Farmer’sprose style is more ornate and more replete with classical allusions than is Smith’s.”[9]

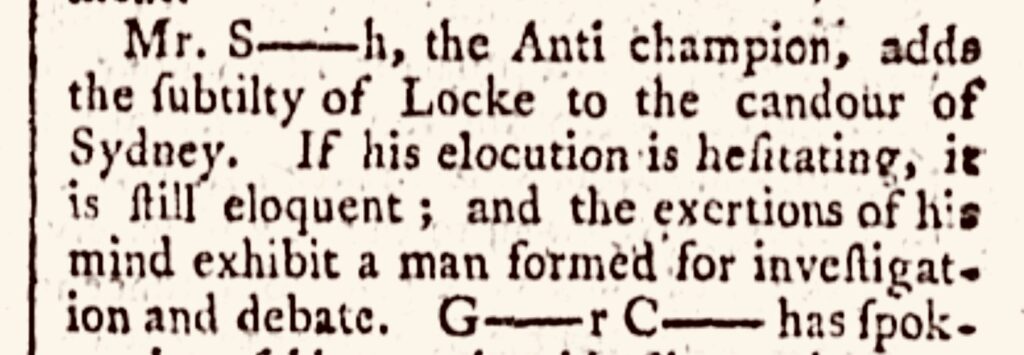

This comparison is consistent with efforts by scholars to categorize Antifederalist schools of thought. For example, Saul Cornell describes Brutus as a “middling” Antifederalist.[10] In comparison, the Federal Farmer arguably falls into the “elite” strand of Antifederalist thinking.[11] As noted by David J. Siemers, elite Antifederalists quoted from a “broad array” of sources, compared to the middling Antifederalists who quoted “more familiar sources, like John Locke or the Bible.”[12] This matches Michael J. Faber’s similar classifications of Brutus as a “Power Anti-Federalist” and the Federal Farmer as a “Rights Anti-Federalist.”[13]

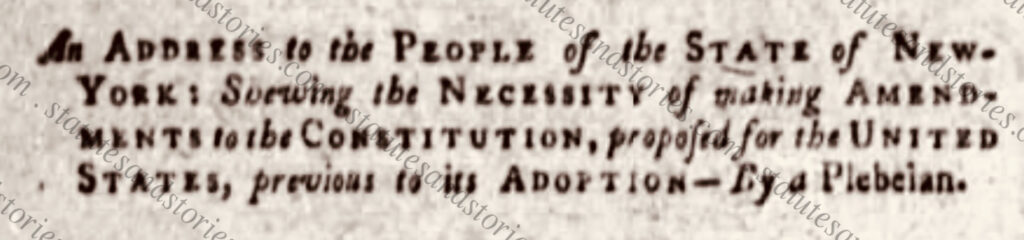

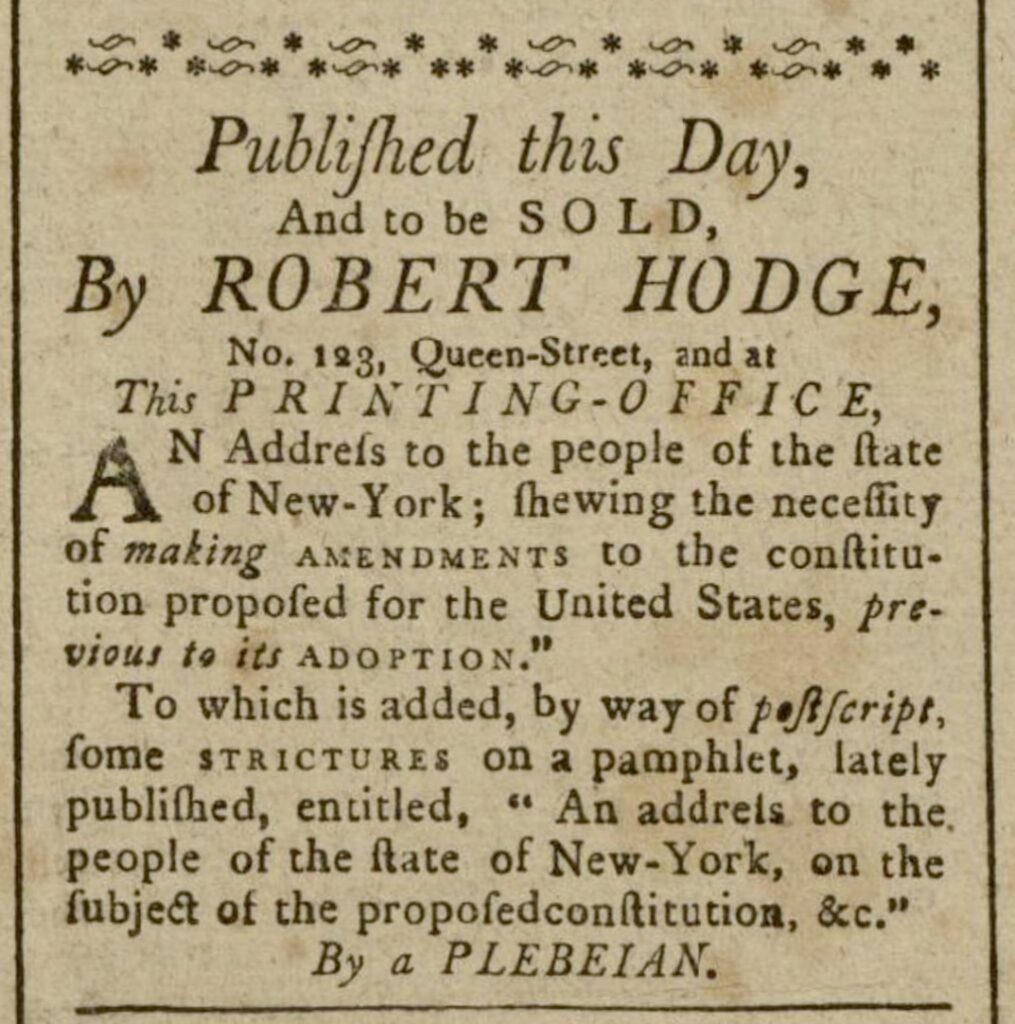

A Plebeian’s frequent use of biblical references aligns with Smith/Brutus

The final Brutus essay, Brutus 16, was published on April 10 in Thomas Greenleaf’s New York Journal.[14] A week later Greenleaf’s newspaper advertised on April 17 that a twenty-six page pamphlet by A Plebeian was now available for sale.[15] The election of delegates to the New York ratification convention was scheduled to begin on April 29th.[16]Although Brutus 16 contemplated that it would be followed by a future 17th essay, it appears that Brutus’s efforts were redirected into what became A Plebeian.[17] If so, A Plebeian can properly be considered as Smith’s final Brutus essay (and a magnum opus of sorts), timed to correspond with the pending election of delegates to Poughkeepsie.

It is noteworthy that Brutus 1 begins by describing the decision facing America as the most important question ever proposed “of any people under heaven.” Brutus warns that if the decision “be a wise one” calculated to preserve the invaluable blessings of liberty, “generations to come will rise up and call you blessed.” With this phrase, Brutus invokes Mary’s prediction of praise by future generations, as recounted in the Gospel of Luke. Similarly, A Plebeian opens with an extended discussion of Paul’s conversation with King Agrippa. It should thus not be surprising that the final paragraph of A Plebeian ends with a prayer from the book of Psalms, which completes the circle.

Connecting the dots, Brutus 1 begins with the prospect of future generations rising up “to call you blessed,” based on the wisdom of your decision. Plebeian completes what can be viewed as an extended sermon with a prayer for wisdom, as the voters of New York headed to the polls. Brutus 1 describes the ratification vote as “the most important question” ever proposed “of any people under heaven.” Plebeian concludes with a prayer that “heaven inspire you with wisdom” and preserve our country while the “sun and moon endure.” Thus, the beginning of Brutus 1 perfectly aligns with the final paragraph of Plebeian:

May heaven inspire you with wisdom, union, moderation and firmness, and give you hearts to make a proper estimate of your invaluable privileges, and preserve them to you, to be transmitted to your posterity unimpaired, and may they be maintained in this our country, while Sun and Moon endure.

While it is true that Plebeian contains a postscript after this concluding paragraph, it is clear that the postscript was specifically added after “the foregoing pages have been put to the press.” In other words, the purpose of Plebeian’s postscript was to directly respond to John Jay’s recently published pamphlet. Accordingly, the beginning of Brutus 1 and the conclusion of Plebeian flow together as one cohesive whole, tied together with related biblical references.

A further example connecting Brutus and Plebeian is the recognition in Brutus 1 that “perfection is not to be expected in any thing that is the production of man.” Brutus 1 explains that he would have held his peace if he didn’t believe that the Constitution was fundamentally defective.[18] The final paragraph of Plebeian connects with this same theme. Plebeianreminds his readers that “[i]t must be recollected, that when this plan was first announced to the public, its supporters cried it up as the most perfect production of human wisdom.” Plebeian reinforces the point by referring to a speech by Democritus (Benjamin Rush) which “went so far, in the ardour of his enthusiasm in its favour, as to pronounce, that the men who formed it were as really under the guidance of Divine Revelation, as was Moses, the Jewish lawgiver.”[19] Yet now, on the verge of the New York ratification vote,[20] Plebeian observes “[t]he same men who held it almost perfect, now admit it is very imperfect; that it is necessary it should be amended.”

The following chart illustrates biblical references found in A Plebeian, which is also believed to have been written by Melancton Smith:

| Biblical References by Plebeian | ||

| A Plebeian 1st paragraph | “As the favourers of the constitution, seem, if their professions are sincere, to be in a situation similar to that of Agrippa, when he cried out upon Paul’s preaching—“almost thou persuadest me to be a christian,” I cannot help indulging myself in expressing the same wish which St. Paul uttered on that occasion, “Would to G-d you were not only almost, but altogether such an one as I am.” But alas, as we hear no more of Agrippa’schristianity after this interview with Paul, so it is much to be feared, that we shall hear nothing of amendments from most of the warm advocates for adopting the new government, after it gets into operation.” | Acts 26:28–29 |

| A Plebeian | “Does not every man sit under his own vine and under his own fig-tree, having none to make him afraid?” | Micah 4:4 |

| A Plebeian | “One gentleman in Philadelphia went so far, in the ardour of his enthusiasm in its favour, as to pronounce, that the men who formed it were as really under the guidance of Divine Revelation, as was Moses, the Jewish lawgiver.” | |

| A Plebeian | “The present is the most important crisis at which you ever have arrived. You have before you a question big with consequences, unutterably important to yourselves, to your children, to generations yet unborn, to the cause of liberty and of mankind; every motive of religion and virtue” | |

| A Plebeian | “The farmer cultivates his land, and reaps the fruit which the bounty of heaven bestows on his honest toil.” | |

| A Plebeian ending | “May heaven inspire you with wisdom, union, moderation and firmness, and give you hearts to make a proper estimate of your invaluable privileges, and preserve them to you, to be transmitted to your posterity unimpaired, and may they be maintained in this our country, while Sun and Moon endure.” | Psalm 72:5 |

The biblical references in Smith’s convention speeches align with Brutus/Plebeian

The New York ratification convention was dominated by two speakers, Melancton Smith and Alexander Hamilton.[21]During the period when shorthand notes were being taken, Smith delivered nineteen speeches, more than any other Antifederalist speaker.[22] Unfortunately, Francis Childs stopped transcribing the New York Convention speeches after July 2.[23] Yet, it does not appear that Smith lost any steam as the Convention continued for another three weeks through July 26. For example, DeWitt Clinton described Smith’s speech of July 11 as “very long and masterly.”[24]

The following chart displays biblical and religious references in Smith’s convention speeches, including more than half a dozen examples with Smith’s very first convention speech on June 20:

| Biblical References in Smith’s convention speeches | ||

| June 20 speech | “the great number of souls were spread over this extensivecounty” | |

| June 20 speech | “The nation of Israel having received a form of civil government from Heaven, enjoyed it for a considerable period; but at length labouring under pressures, which were brought upon them by their own misconduct and imprudence, instead of imputing their misfortunes to their true causes, and making a proper improvement of their calamities, by a correction of their errors, they imputed them to a defect in their constitution” | 1 Samuel 8:11-18 |

| June 20 speech | “they rejected their Divine Ruler, and asked Samuel to make them a King to judge them, like other nations. Samuel was grieved at their folly; but still, by the command of God, he hearkened to their voice; tho’ not until he had solemnly declared unto them the manner in which the King should reign over them. “This, (says Samuel) shall be the manner of the King that shall reign over you.” | |

| June 20 speech | “He had one more observation to make, to show that the representation was insufficient – Government, he said must rest for its execution, on the good opinion of the people, for if it were made in heaven, and had not the confidence of the people, it could not be executed: that this was proved, by the example give by the gentleman of, the Jewish theocracy.” | |

| June 20 speech | “Golden images, with feet part of iron and part of clay” | Daniel 2:31-33 |

| June 20 speech | “Beast dreadful and terrible, and strong exceedingly, having great iron teeth, which devours, breaks in pieces, and seeps the residue with his feet” | Daniel 7:7 |

| June 20 speech | “how long it might continue, God only knew!” | |

| June 25 speech | “Heaven only knows when they will be.” | |

| June 27 speech | “with as much Zeal as now used to shew that the Con. is perfect and like a System framed in Heaven & given to us by express Revelation” |

Biblical references in Smith’s correspondence are consistent with Brutus/Plebeian

While Melancton Smith has not been studied as closely as other more prominent members of the founding generation, historians have uniformly recognized Smith’s religious background and faith. It is believed that the first biographical sketch about Smith was written in the late 19th century. Without elaboration, Smith was described as “a strict churchman.”[25] In the 1940s, Julian Boyd wrote an entry in the Dictionary of American Biography indicating that Smith manifested a “life-long interest” in religion and metaphysics.[26] Boyd observed that Smith helped organize the Washington Hollow Presbyterian Church in 1769, where he owned a pew. Two hundred years later, historian Broadus Mitchell described Smith as an “an ardent Presbyterian.”[27] By far the most detailed account of Smith’s life can be found in Robin Brooks’ Ph.D. dissertation which describes Smith as a “pillar” of his church.[28]

Brooks confirms that “[t]here is little question that Melancton Smith remained a devout Christian” during his lifetime.[29]In particular, Brooks points to a letter written by Smith to Gilbert Livingston where “Smith burst out in praise of the Kingdom of Heaven and its Ruler who shapes all mortal acts to His good purposes.”[30] A close examination of Smith’s surviving correspondence reveals biblical references and allusions which align with his convention speeches, the letters of Brutus and the Plebeian pamphlet. For example, Smith’s 1 January 1789 letter to Gilbert Livingston cites to Psalms as does Plebeian.[31]

As a delegate to the New York Provincial Congress from Dutchess County, Smith voted with his delegation in favor of the controversial resolution to open each daily session with a prayer.[32] Smith’s religious convictions were also evident in June of 1775 when he sought to add a “right of conscience,” otherwise known as freedom of religion, to the proposed Plan of Accommodation with the British. This early work would subsequently serve as a model for New York’s first constitution.[33]

The first example of Smith’s religiosity expressed in his correspondence dates back to 1771. In a letter from Smith to his friend Henry Livingston, Smith invokes the blessings of Heaven three times. These examples of Smith seeking the blessings from Heaven (“May the smiles of a kind and indulgent Heaven cheer you”; “may Heaven grant”; “Heaven bless you”) align with references to heaven in Smith’s convention speeches (on June 20, 25, 27), five of Brutus’s letters (Brutus1, 5, 7, 10, 15) and two examples in Plebeian. The 1771 letter also refers to “eternity,” “a God of infinite Wisdom & immaculate goodness,” “divine Providence,” and “egyptian Bondage.”

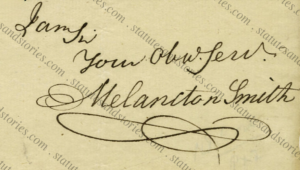

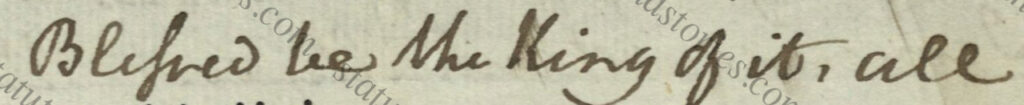

Smith’s letter to Gilbert Livingston two decades later is consistent with this same religious perspective. Writing in January of 1789, Smith updated Livingston as to post ratification developments in New York City. Smith reassured Livingston that he retained the same sentiments as he ever did, that the new Constitution was not “of divine Original.” Smith uses a metaphor from Psalms 125 that they “ought therefore to strive to maintain our union firm and immoveable as the mountains”[34] in pursuing their object of amendments. Smith also quotes Psalms 76 as follows:

“Blessed be the king of it, all things are under his controul, and however great the ambition of frail mortals may be, he will conduct every event to produce the best end. For even the wrath of Man shall praise him and the remainder will he restrain.”

It is clear that Smith took comfort in scripture as he declared, “May we stand in our Lot in that Kingdom,” referring to the “Kingdom which can never be moved.”[35] He concluded his letter with the request that Livingston “[t]ell all our friends to stand fast.”

The following chart displays biblical and religious references in Smith’s correspondence which is consistent with Brutus, Plebeian and Smith’s convention speeches:

| Biblical References in Melancton Smith Correspondence | |

| Smith to Henry Livingston 2 Feb 1771 | “May the smiles of a kind an dindulgent Heaven cheer you while travelling through the gloomy vale of life, till you arrive to the bright regions of a happy Eternity….Were it not that I firmly believed a God of infinite Wisdom & immaculate goodness presided over Human Affairs, who is able & determined to so dispose of Things as finally, to, bring about the Greatest Good, I should be quite distracted with the shameless Conduct of Men in Power.” |

| Smith to Henry Livingston 2 Feb 1771 | “I think, we are bound to be very grateful to divine Providence, that the majority of the House of Asses, have not understanding equal to the Wickedness of their Hearts, for if this was the case, we should have awful Reason to fear, the province would soon be ensalved in egyptian Bondage.” |

| Smith to Henry Livingston 2 Feb 1771 | “may Heaven grant a dissolution and open peoples eyes to a sese of their true interest…..I am to set out by leave of providence, on a journey to N. England….expect much pleasure in explaining philosophical & theological subjects. Heaven bless you.” |

| Smith to A Yates, 23 Jan 1788 | “I could easily lengthen my epistle but I am in haste” |

| Smith to Gilbert Livingston, 1 Jan 1789 | “…that Kingdom which can never be moved. May we stand in our lot in that kingdom.” |

| Smith to Gilbert Livingston, 1 Jan 1789 | “Blessed be the king of it, all things are under his controul, and however great the ambition of frail mortalsmay be, he will conduct every event to produce the best end. For even the wrath of Man shall praise him and the remainder will he restrain.” |

| Smith to Gilbert Livingston, 1 Jan 1789 | “…who did not believe the new constitution was of divine Original.” |

| Smith to Gilbert Livingston, 1 January 1789 | “We ought therefore to strive to maintain our union firm and immoveable as the mountains” |

| Smith to John Smith 10 January 1789 | “engaging heaven on their side” |

| Smith to James Cooper, 28 March 1795 | “for Gods sake change your course” |

Smith’s ardent and abiding opposition to slavery which aligns with Brutus

As discussed above, Melancton Smith was a “strict churchman” who manifested a “life-long interest” in religion. Both Smith and Brutus frequently used biblical imagery and references. Not surprisingly, Smith was both an “ardent Presbyterian” and an ardent opponent of slavery. Brutus 3 declared that slavery was “in defiance of every idea of benevolence, justice, and religion, and contrary to all the principles of liberty, which have been publickly avowed in the late glorious revolution.” Brutus’s outspoken criticism of slavery aligns with Smith’s June 20 convention speech and abiding opposition to slavery.

While serving in Congress in 1787 Smith was a member of the Congressional committee that drafted the Northwest Ordinance which banned slavery in the territories acquired from Britain during the war.[36] Unlike other Antifederalist delegates to the New York ratification convention who owned slaves, Smith was one of nineteen founders of the New-York Manumission Society (NYMS). Consistent with his religious background, Smith assumed an active and longstanding leadership role with the NYMS.

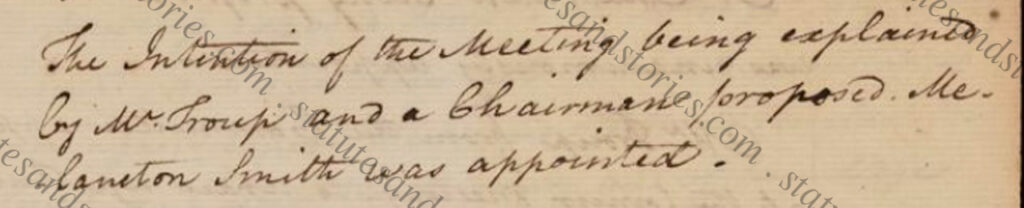

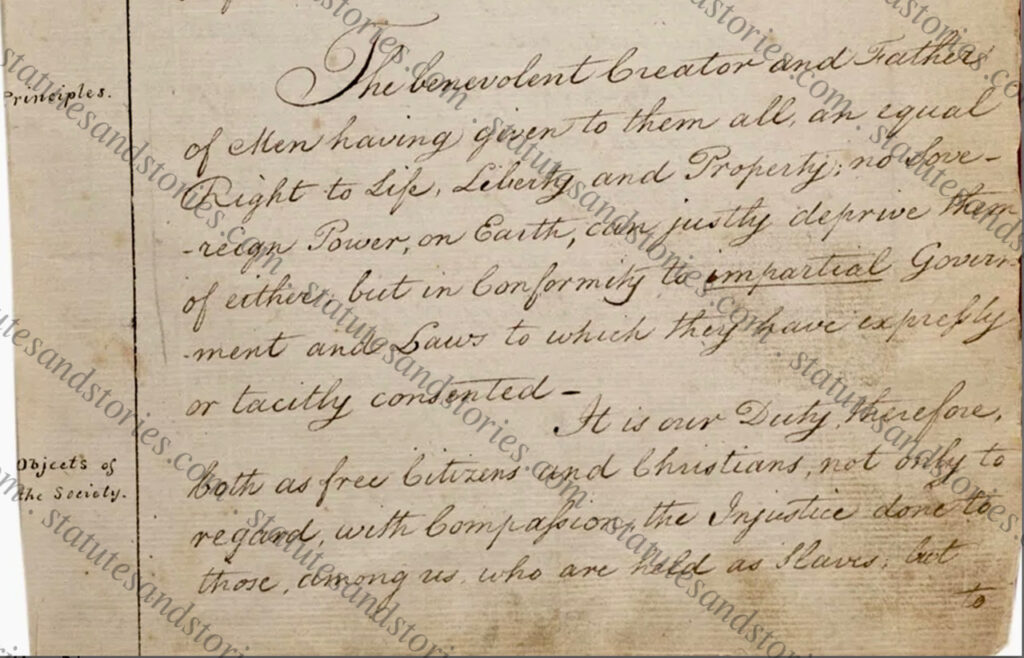

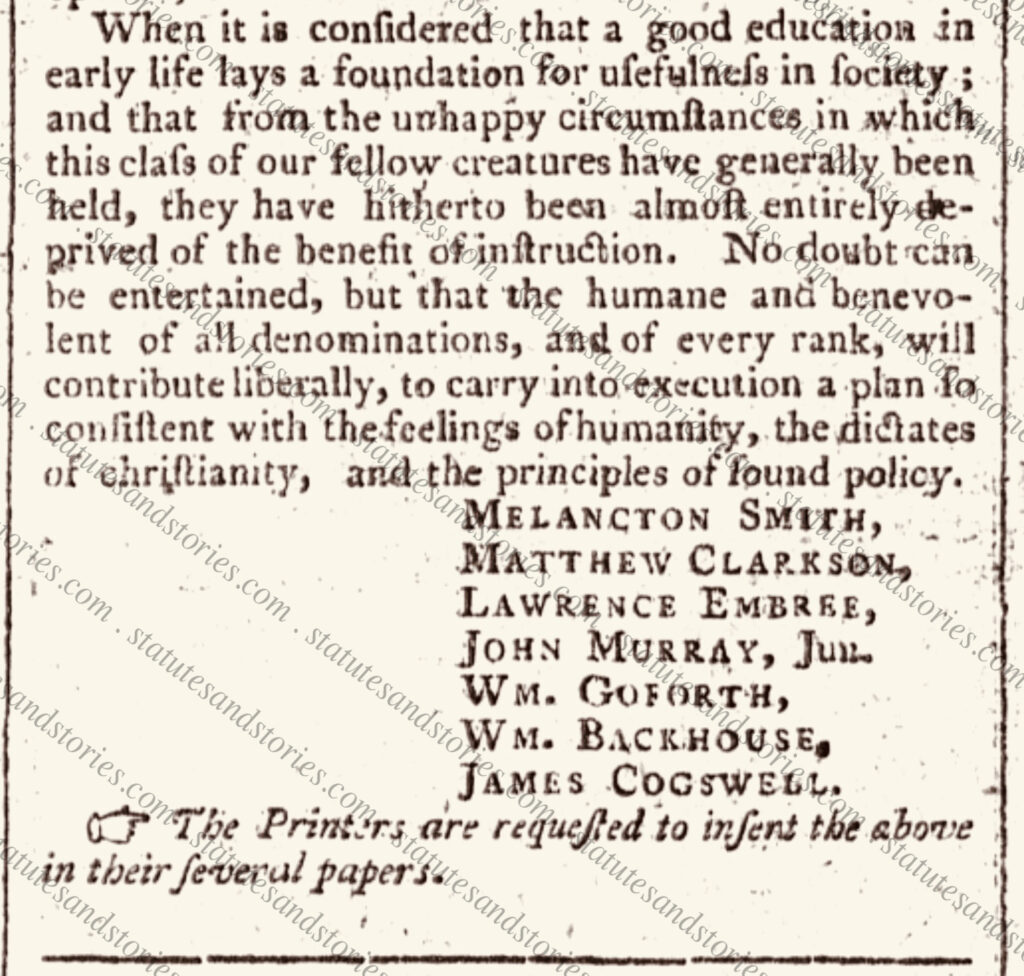

Smith was elected chairman of the NYMS at its first meeting held on January 25, 1785 in Simmons’ Tavern in New York City.[37] Click here for a discussion of Simmons’ Tavern. Smith was one of five members on the committee that prepared the NYMS’ statement of rules and principles which fully aligns with Brutus 3 and Smith’s New York ratification convention speech on June 20th.

Borrowing from the Declaration of Independence, the NYMS statement of rules and principles declared that “all men had an equal right to life, liberty and property.” The NYMS statement further declared that “free citizens and Christians” had a duty to recognize injustice and act with compassion to spread liberty “by lawful Ways and Means.” Thus, the NYMS was established with the goal of enabling slaves to “share, equally with us, in that civil and religious Liberty” with which providence had blessed the American states. The same concept would be used by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton with the Declaration of Sentiments which kicked off the Women’s Rights movement in Seneca Falls in July of 1848.

The first two paragraphs of the NYMS declaration setting forth its “principles” and “objects” are copied below:

The benevolent Creator and Father of Men having given to them all, an equal Right to Life, Liberty and Property; no Sovereign Power, on Earth, can justly deprive them of either, but in Conformity to impartial Government and Laws to which they have expressly or tacitly consented —

It is our Duty therefore, both as free Citizens and Christians, not only to regard, with Compassion, the Injustice done to those, among us who are held as Slaves, but to endeavour, by lawful Ways and Means, to enable them to Share, equally with us, in that civil and religious Liberty with which an indulgent Providence has blessed these States; and to which these, our Brethren, are by Nature, as much entitled as ourselves.

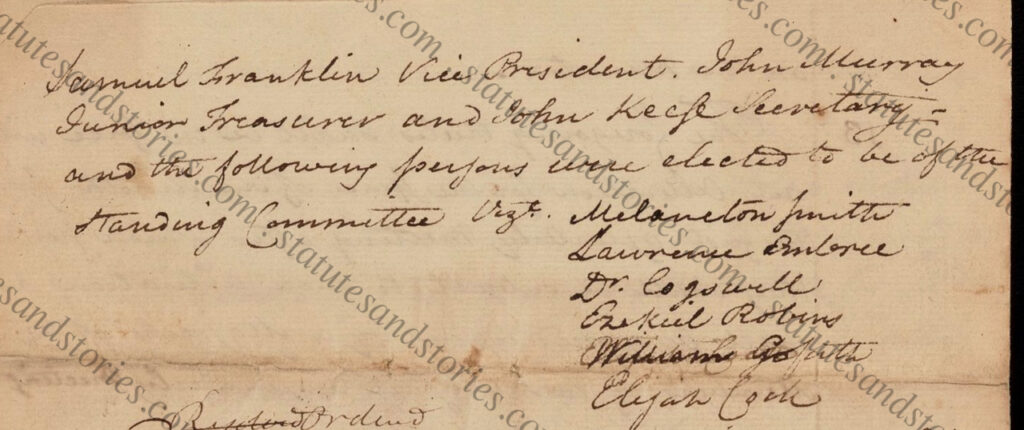

After chairing the inaugural meeting of the NYMS, Smith continued in an active leadership role.[38] Smith was the first member elected to the six-member standing committee charged with implementing the society’s agenda. Among other things, the committee prepared and presented a petition to the New York legislature for an act gradually abolishing slavery in New York, publicized the NYMS’ activities, and collected dues.[39]

At its May 1785 meeting, Smith’s committee reported on the efforts to publicize the society’s work and objective “to remove that Prejudice which has unhappily prevailed over Justice and the Dictates of Religion.” Working with dispatch, the standing committee also reported on the society’s petition to the New York legislature for the abolition of slavery which was signed by “a great number of respectable Persons.”[40] Having served in the New York legislature and as a member of Congress, Smith was frequently selected as a NYMS lobbyist for the New York legislature and Congress.[41]In January of 1788 Smith was appointed to a committee that petitioned the legislature to prevent the exportation of slaves from New York.[42]

Smith’s committee also worked on securing freedom for individual slaves and “to prevent kidnappers from leaving the city on ships with free Black people onboard, to intervene in situations where slaves were being improperly treated by their owners, and forced jailers in the city to release those who had been illegally detained.”[43] For example, Smith was involved with the filing of a habeas corpus petition to prevent a free Black citizen kidnapped in Connecticut from being transported to South Carolina.[44]

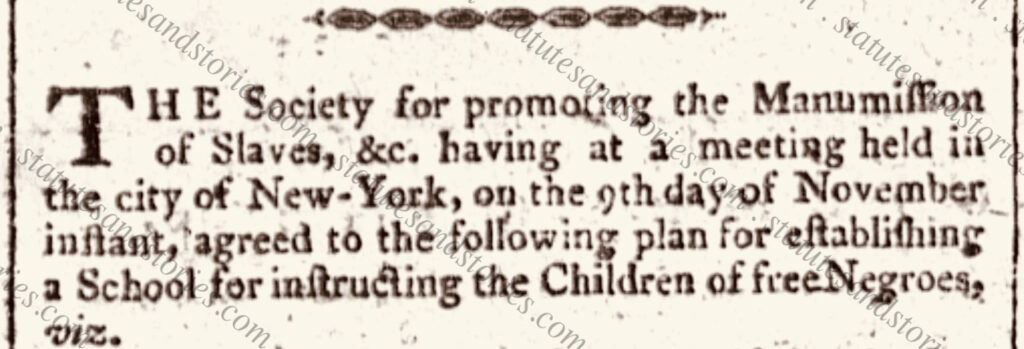

Another objective of the NYMS was to provide education. One way the NYMS did so was with the founding of the African Free School. Smith was the first trustee appointed when the school was established in November of 1787.[45] A related problem confronted by the committee involved situations where manumissions by wills were being ignored by surviving family members. Although some slave owners wanted to free their slaves upon their death, widows and family sought “to keep the slave in their household to avoid having to support the slave if he ever became unable to care for himself.”[46]

When John Jay was appointed chief justice of the United States and Congress relocated from New York to Philadelphia, Jay and Alexander Hamilton were forced to step down as the first and second presidents of the NYMS. Smith was elected vice-president after their departure. He would be reelected as the vice president of the NYMS in 1792 and 1793.[47]

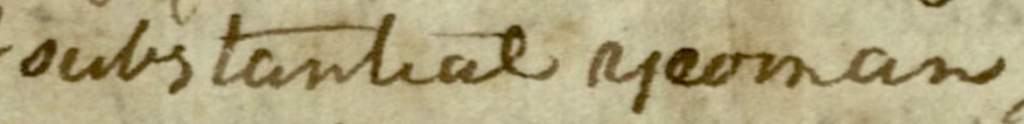

A fundraising subscription for the African Free School spearheaded by Smith[48] is pictured below. The concluding paragraph of the detailed description contains sentiments that align with Brutus 3 and Smith’s June 20th convention speech. For example, Brutus 3 condemned slavery and referred to slaves as “unhappy people” torn from their tender connections and as “poor unhappy creatures.” This aligns with Smith’s subscription for the NYMS which referred to the “unhappy circumstances in which this class of our fellow creatures have been held.” Moreover, Smith’s subscription sought donations from “humane and benevolent” New Yorkers to implement their plan “consistent with the feelings of humanity” while Brutus 3 referred to slaves being held in bondage in defiance of every idea of “benevolence, justice and religion” and condemned the “inhuman traffic of importing slaves.”

Unlike other prominent New Yorkers who merely professed opposition to slavery, Smith was a committed member of the NYMS who “rendered yeoman service to the society.”[49] According to Zuckert and Webb, “Smith’s outspoken opposition to slavery, as demonstrated by his opposition to the three-fifths clause at the ratifying convention, his membership on the committee that drafted the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 barring slavery from the territories, and his eleven-year membership and active participation in the New York Manumission Society, indicate that he was quite capable of denouncing slavery in the terms in which Brutus did.”[50]

Almost two decades ago, Zuckert and Webb contemplated a Melancton Smith “circle.” Based on the totality of newly compiled attribution evidence it is now time to affirmatively recognize that Elbridge Gerry was the Federal Farmer and Melancton Smith was Brutus. Click here for a link to Part 1 of the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis (“FEAT”). Set forth below are detailed linguistic fingerprints supporting the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.”

Smith’s linguistic fingerprints which align with Brutus and Plebeian

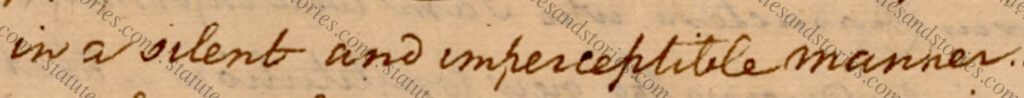

Gradual expansion of federal power in a “silent and imperceptible manner” by “insensible degrees”

Set forth below is a detailed discussion of Melancton Smith’s linguistic fingerprints which taken together prove that he was the Antifederalist Brutus. As indicated in Part 2, the timing and content of Smith’s 23 January 1788 letter to Abraham Yates provides powerful attribution evidence. Smith worried that the proposed judicial powers under Article III would clinch all other powers and extend them in a “silent and imperceptible manner to any thing and every thing.” In evaluating Article III, Brutus 11 used the identical phrase that judicial power would operate in a “silent and imperceptible manner” resulting in “an entire subversion of the legislative, executive and judicial powers of the individual states.”[51]As this unique phrase was used by Smith prior to Brutus 11, it is properly viewed as a useful attribution fingerprint.

The same concern was expressed by Smith in Brutus 4, indicating that federal expansion would occur silently as the chains were gradually rivetted together until it was too late:

This may be effected constitutionally, and by one of those silent operations which frequently takes place without being noticed, but which often produces such changes as entirely to alter a government, subvert a free constitution, and rivet the chains on a free people before they perceive they are forged.[52]

Brutus 15 raises the similar concern that the judicial power granted to the Supreme Court was immense and would gradually expand federal control “by insensible degrees” over time. As described by Brutus 15:

Perhaps nothing could have been better conceived to facilitate the abolition of the state governments than the constitution of the judicial. They will be able to extend the limits of the general government gradually, and byinsensible degrees, and to accommodate themselves to the temper of the people.

Writing as Plebeian Melancton Smith expressed the identical concern that the federal government would gradually expand over time “by insensible degrees.” According to Plebeian:

When the compact is once formed and put into operation, it is too late for individuals to object. The deed is executed—the conveyance is made—and the power of reassuming the right is gone…. It steals, by insensible degrees, one right from the people after another, until it rivets its powers so as to put it beyond the ability of the community to restrict or limit it.

After the Constitution was ratified Melancton Smith continued to actively support constitutional amendments. Writing as a Federal Republican[53] in December of 1788, Smith used the same phrase to express the concern that the federal government would gradually annihilate the state governments as it expanded “by insensible degrees.” According to the Federal Republican, amendments were necessary to prevent the establishment of a dangerous system of government which its supporters sought “to fix over the people of this country by insensible degrees, and without their perceiving it until it is accomplished.”

Accordingly, the phrases “silent and imperceptible manner” and “by insensible degrees” are properly recognized as Smith’s unique signature fingerprints. The two phrases are not used by other Antifederalists, despite the fact that the Federal Farmer, Cato, Centinel and other Antifederalists frequently made overlapping arguments.[54]

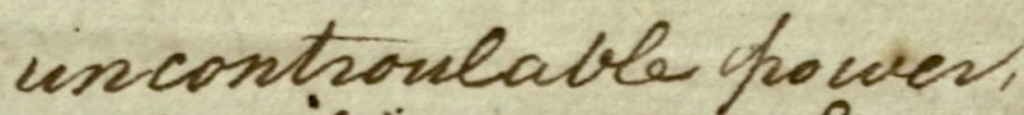

“totally independent” and “uncontroulable power” which would “swallow up” the states

Smith’s 23 January 1788 letter to Abraham Yates, Jr. also objected that the federal courts would have powers that were “totally independent, uncontroulable and not amenable to any other power.”[55] This directly aligns with the concern in Brutus 11 that the courts would be rendered “totally independent” and Brutus 12 that the courts would be vested with “supreme and uncontroulable power.” This phraseology and concern that a creeping federal government would eventually annihilate the states – and individual rights – appears in Brutus 1, 6 and 12. Smith makes the same argument in his convention speeches on June 21 and July 1.

Set forth below are examples of alignment between Brutus and Melancton Smith’s convention speeches illustrating his concern for the danger of a “totally independent” judiciary with the “uncontrollable power” of judicial review. In the following examples, Smith (Brutus) variously refers to “absolute and uncontroulable power,” “great and uncontroulable powers,” and “supreme and uncontroulable power” of the federal government:

- Brutus 1: “This government is to possess absolute and uncontroulable power, legislative, executive and judicial, with respect to every object to”; “But what is meant is, that the legislature of the United States are vested with the great and uncontroulable powers, of laying and collecting taxes, duties, imposts, and excises; of regulating trade, raising and supporting armies, organizing, arming, and disciplining the militia, instituting courts, and other general powers. And are by this clause invested with the power of making all laws, proper and necessary, for carrying all these into execution; and they may so exercise this power as entirely to annihilate all the state governments, and reduce this country to one single government.”

- Brutus 6: “Upon the whole, I conceive, that there cannot be a clearer position than this, that the state governments ought to have an uncontroulable power to raise a revenue, adequate to the exigencies of their governments; and, I presume, no such power is left them by this constitution.” (concluding lines)

- Brutus 12: “And the courts are vested with the supreme and uncontroulable power, to determine, in all cases that come before them, what the constitution means; they cannot, therefore, execute a law, which, in their judgment, opposes the constitution, unless we can suppose they can make a superior law give way to an inferior.”

- June 21 convention speech: “The [– – –] [possess?] an uncontroulable power, to command the property of the Citizens, and they will have the power without restriction almost exclusively to direct all the force of the Country whether militia or regular Troops”

- July 1 convention speech: I admitted that the States wd. have concurrent jurisdn., in laying taxes, but I did not mean by this that they would have supreme, oruncontroulable power on this head—Two powers may exercise jurisdiction over the same object, and yet both be subordt. to a higher, and the one subordt. to the other”

While concern over federal power was routinely expressed by other Antifederalists, the phrase “uncontroulable power” appears to only have been used by Brutus.[56] This is not to say that Antifederalists disagreed with Brutus. To the contrary, Antifederalists commonly objected to the “unlimited power” proposed to be granted under the Constitution.[57]Indeed, Smith also used the phrase “unlimited power” which was synonymous with his signature phrase “uncontroulable power.”[58]

A related Smith fingerprint is the concern that the federal government would “swallow up” the states, which would be gradually annihilated under the Constitution. Smith used the phrase “swallow up” in Brutus 1, 6 and as Plebeian. He used the same phrase in a convention speech on June 27. This aligns with his related concern over gradual but “complete abolition of the state governments.” Examples of the use of the phrase “swallow up are set forth below, beginning with Brutus 1:

- Brutus 1: These courts will be, in themselves, totally independent of the states, deriving their authority from the United States, and receiving from them fixed salaries; and in the course of human events it is to be expected, that they will swallow up all the powers of the courts in the respective states. (Oct 18)

- Brutus 6: It is an important question, whether the general government of the United States should be so framed, as to absorb and swallow up the state governments? or whether, on the contrary, the former ought not to be confined to certain defined national objects, while the latter should retain all the powers which concern the internal police of the states?

- Brutus 6: A power that has such latitude. which reaches every person in the community in every conceivable circumstance, and lays hold of every species of property they possess, and which has no bounds set to it. but the discretion of those who exercise it[.] I say, such a power must necessarily, from its very nature, swallow up all the power of the state governments.

- Plebeian: But it never was in the contemplation of one in a thousand of those who had reflected on the matter, to have an entire change in the nature of our federal government—to alter it from a confederation of states, to that of one entire government, which will swallow up that of the individual states.

- June 27 convention speech: the powers of the confederacy will swallow up those of the members. I do not suppose that this effect will be brought about suddenly.

Admittedly, other Antifederalists used the phrase “swallow up,” but Smith (Brutus 1) used the phrase early in the ratification debate on October 18. While they no doubt agreed with the same concern, neither the Federal Farmer nor Cato used this identical fingerprint. Not surprisingly, Publius never used the phrase “swallow up.” Centinel II used the phase twice on October 24, but he was potentially lifting it from Brutus 1 published a week earlier. A related phrase used by Brutus was the observation that the states would “dwindle away.”[59] In his speech on June 25 Smith used the phrase “dwindle into insignificance.”[60]

Smith expressed the same concern when he warned that the states would be gradually “annihilated” / “abolished.” These terms are too common to be categorized as a signature fingerprint of Brutus. Nonetheless the following examples illustrate Brutus’s repeated warnings of the threat posed by the federal government to the states, which would gradually be “annihilated” / “abolished” / “swallowed up” until they “melted away”:

- Brutus 1: all that is reserved for the individual states must very soon be annihilated, except so far as they are barely necessary to the organization of the general government.

- June 27 convention speech: On the whole, it appears to me probable, that, unless some certain specific source of revenue is reserved to the states, their governments, with their independency, will be totally annihilated.

- Federal Republican No. 2: it will annihilate the state governments on whom we must depend

- Brutus 5: the complete abolition of the state governments

- Brutus 15: Perhaps nothing could have been better conceived to facilitate the abolition of the state governments than the constitution of the judicial. They will be able to extend the limits of the general government gradually, and by insensible degrees, and to accomodate themselves to the temper of the people.

- Brutus 15: I have, in the course of my observation on this constitution, affirmed and endeavored to shew, that it was calculated to abolish entirely the state governments, and to melt down the states into one entire government, for every purpose as well internal and local, as external and national.

- June 27: I contemplate the abolition of the state constitutions as an event fatal to the liberties of America.

For Brutus, this threat of annihilation/abolition of the states came from several directions, including the unlimited taxing power of Congress, the necessary and proper clause, the Preamble, and judicial supremacy.[61]

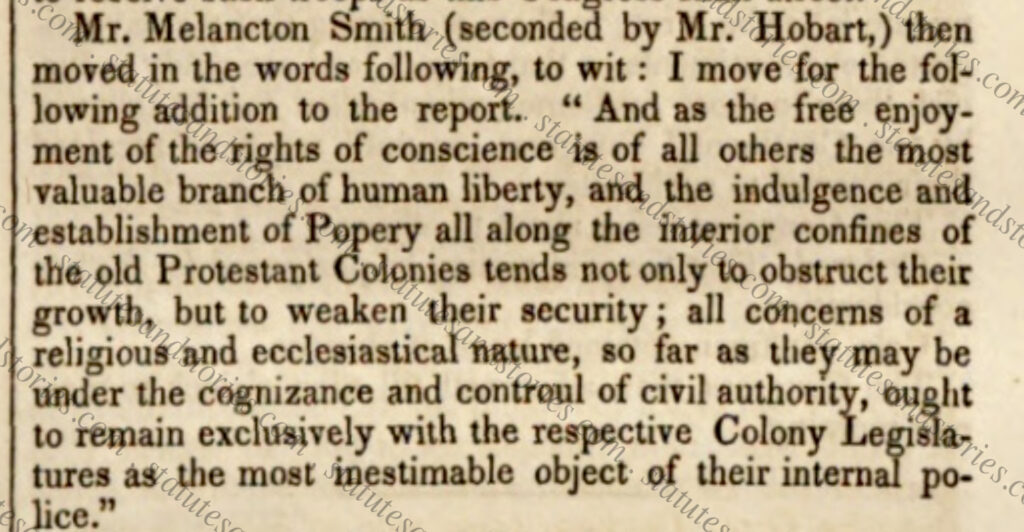

“Internal police” of the respective states

The phrase “internal police” has fallen from the modern lexicon. Today the same concept is referred to as the “police power,” which is generally reserved to the states and the people under the Tenth Amendment. Melancton Smith believed that the police power was the most important end of government. The following examples illustrate that Smith sought to project the “internal police” of the colonies from the British as early as 1775. A decade later, Smith raised alarms about federal encroachment on the internal police during the impost battle in 1786. The same phrase is used in Brutus 2, 6, 7, and 11. Smith also used a variant of the phrase, “the police” “state police” and “internal matters.”

In June of 1775 Melancton Smith was a delegate to the New York Provincial Congress. During negotiations with the British, New York offered a Plan of Accommodation which sought to protect basic liberties. The proposed plan lacked an article protecting freedom of religion, which was also known as the “right of conscience.” As discussed in a letter from Gouverneur Morris to John Jay, an article was proposed to address freedom of religion. The following proposed article was Melancton Smith which referred to the colonial rights for freedom of conscience which Smith described as “the most inestimable object of their internal police”:

“And as the free enjoyment of the rights of conscience is of all others the most valuable branch of human liberty, and the indulgence and establishment of Popery all along the interior confines of the old Protestant Colonies tends not only to obstruct their growth, but to weaken their security; all concerns of a religious and ecclesiastical nature, so far as they may be under the cognizance and controul of civil authority, ought to remain exclusively with the respective Colony Legislatures as the most inestimable object of their internal police.”[62]

In July of 1786, Smith gave a speech in Congress defending New York’s conditional adoption of the Impost of 1783. As discussed in Part 2, Smith argued that states should be free to implement the impost as they saw fit as long as revenue was generated. Smith pointed to examples from the other states which experimented with different means of collecting the impost while preserving their internal police. With regard to legislative protections, Smith indicated: “Connect[icut] provides the Ordinances shall not be incons[is]t[ent] with the cons[titution] & internal police of the State.” With regard to judicial projections, Smith explained: “Connecticut & Delaware in particul. by the reserve they make limit it, the one by the court & internal police, & the other bv the constant. & Laws, & the others limit the mode of trial to be according to the Laws & cons[titutions].”

Subsequent examples of Smith using the phrase internal police are set forth below:

- Brutus 3: “the powers vested in this branch of the legislature are very extensive, and greatly surpass those lodged in the assembly, not only for general purposes, but, in many instances, for the internal police of the states.”

- Brutus 6 (1st sentence): “It is an important question, whether the general government of the United States should be so framed, as to absorb and swallow up the state governments? or whether, on the contrary, the former ought not to be confined to certain defined national objects, while the latter should retain all the powers which concern the internal police of the states?

- Brutus 6: “If on the contrary it can be shewn, that the state governments are secured in their rights to manage the internal police of the respective states, we must confine ourselves in our enquiries to the organization of the government and the guards and provisions it contains to prevent a misuse or abuse of power.”

- Brutus 7: The most important end of government then, is the proper direction of its internal police, and œconomy; this is the province of the state governments, and it is evident, and is indeed admitted, that these ought to be under their controul. Is it not then preposterous, and in the highest degree absurd, when the state governments are vested with powers so essential to the peace and good order of society, to take from them the means of their own preservation?

- Brutus 7: “My own opinion is, that the objects from which the general government should have authority to raise a revenue, should be of such a nature, that the tax should be raised by simple laws, with few officers, with certainty and expedition, and with the least interference with the internal police of the states.”

- Brutus 11: “I have not met with any writer, who has discussed the judicial powers with any degree of accuracy. And yet it is obvious, that we can form but very imperfect ideas of the manner in which this government will work, or the effect it will have in changing the internal police and mode of distributing justice at present subsisting in the respective states, without a thorough investigation of the powers of the judiciary and of the manner in which they will operate.”

Smith also used the following variants of the phrase “internal police”:

- June 21: “The same observations will equally apply to almost every power in this govt. that reaches to internal matters”

- June 25: “Answer It will scarce be found that two Men only in the State will be so Superior to all others—If there should be two such they will be sometimes wanted at home to assist in State Police”

- June 26: “Every person who knows the police of the Eastern States knows it is practicable”

- June 30: “They will be under the add[itiona]l inf[luenc]e of fear—they will do all they can to prevent Cong[ress] from interfering in the police—this will have the influence necessary”[63]

- Federal Republican No. 1: “It is of the highest moment that they use this right with prudence and discretion – The change which this new system of government will effect upon the police and condition of the United States will be very material.”

The use of the phrase “internal police” was not unique to Brutus (Smith). Federal Farmer repeatedly used the phrase “internal police.”[64] Antifederalists Luther Martin,[65] Mercy Otis Warren,[66] and Hugh Hughes[67] are examples of Antifederalists who also used the phrase, but not with the same frequency as Smith. Cato and Centinel are examples of Antifederalist who never used the phrase. John Williams used the phrase “internal police” during a speech at the New York convention on June 21, but Williams was quoting almost verbatim from Brutus 6. As Smith stressed the importance of the “internal police” as early as 1775 and again in 1786, the phrase is properly viewed as an attribution fingerprint connecting Melancton Smith with Brutus.

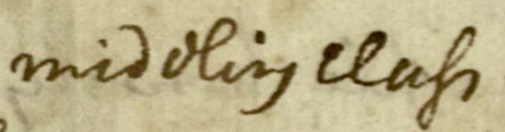

The “middling class” and a “shadow of representation”

A more famous example of a recurring Brutus fingerprint is his repeated concern for the “middling class,” when arguing that representation in the House was defective. Brutus believed that the poor and middling class were most in need of protection, yet representation of the House would primarily consist of the “rich and great.” Brutus variously referred to the middling class “of life,” “of people,” “of citizens,” and “of the community.” The common denominator was Brutus’s concern for an expanded representation of the “middling class” also known as the “yeomanry of the country.”

Examples of Brutus’s use of the phrase “middling class” are set forth below:

- Brutus 3: “will be ignorant of the sentiments of the middling class of citizens”

- Brutus 4: “while the middling class of the community would be excluded”

- Brutus 14: “the poor and middling class of people who in every government stand most in need of the protection of the law”

- Brutus 16: “will possess very little of the feelings of the middling class of people”

- Plebeian: “the middling class”; “every man of middling property”

- June 21: “it should admit those of the middling class of life”

- June 23: “in order to have a true and genuine representation, you must receive the middling class of people into your government”

Writing as Plebeian, Smith addressed his argument to the “common people, the yeomanry of the country” who would be the “principal losers, if the constitution should prove oppressive.” Plebeian observed that when tyranny takes root it produces masters and slaves. Consistent with the terminology employed in Brutus, Smith wrote that “the great and the well-born are generally the former, and the middling class the latter.”[68]

During the New York ratification convention Smith repeatedly argued that the number of representatives in the House should be expanded to better represent the middling class. For Smith, “the best possible security to liberty” was a representative body “composed primarily of respectable yeomanry.” Smith reasoned that when the interest of this class was pursued, the public good was pursued “because the body of the nation consists of this class.”

On June 21 Smith used the phrase “middling class” nearly a dozen times. Among other things Smith argued that the middling class had less temptation, more frugal habits, “better morals and less ambition than the great.”[69] On June 23 Smith summarized his argument that “in order to have a true and genuine representation, you must receive the middling class of people into your government.”[70]

Yet, in his speech of June 21 Smith predicted that “This Government is so constituted, that the representatives will generally be composed of the first class in the community, which I shall distinguish by the name of the natural aristocracy of the country.”[71] Smith feared that “the government will fall into the hands of the few and the great. This will be a government of oppression.” This directly aligns with the fears expressed in Brutus 3 and 4 as follows:

- Brutus 3: “the natural aristocracy of the country will be elected.”

- Brutus 4: “That the choice of members would commonly fall upon the rich and great, while the middling class of the community would be excluded.”

According to Smith’s speech on June 21, due to the inadequate representation in the House the democratic branch would be a “mere shadow of representation.” Smith used this identical expression in Brutus 4. He used substantially similar phraseology in Brutus 3, and 10 as follows:

- Brutus 3: “defective as this representation is, no security is provided, that even this shadow of the right, will remain with the people.”

- Brutus 4 (Nov. 29): “the people have no security that they will enjoy the exercise of the right of electing this assembly, which, at best, can be considered but as the shadow of representation.”

- Brutus 10: “I have, in some former numbers, shewn, that the representation in the proposed government will be a mere shadow without the substance.”

- June 21: “I confess, to me they hardly wear the complexion of a democratic branch—they appear the mere shadow of representation.”

- July 11: “my opinion is, that if it is not amended, that we have during the late revolution been fighting for a shadow….“

The only other pseudonymous writer to use the phrase “shadow of representation” when criticizing the Constitution was the Federal Farmer. Brutus 4 was published on 29 November 1787, preceding the ostensible date Federal Farmer 7 by over a month.[72A] The only speaker at a ratification convention to use the phrase was Melancton Smith on June 21. Smith also repeatedly used the phrase “middling class” on June 21. Accordingly, the use of the phrase “shadow of representation” to describe the inadequate representation of the “middling class” in the House is properly viewed as a powerful attribution fingerprint connecting Melancton Smith with Brutus.

Representatives “should resemble,” not be “mere to strangers” “not acquainted with” their constituents and “void of sympathy”

Smith used several related phrases to express his concern over the inadequacy of representation in the House. Brutusobjected that members of Congress “should resemble” the electorate, be “acquainted with” the voters, not be “mere strangers to” their constituents or otherwise “void of sympathy.” According to Brutus 3, the very concept of representation implies resemblance. As Smith summarized on June 21 at the New York convention, representatives in Congress should provide a “true picture of the people.” The following passage from Brutus 3 aligns with Smith’s speech on June 21:

- Brutus 3: The very term, representative, implies, that the person or body chosen for this purpose, should resemble those who appoint them—a representation of the people of America, if it be a true one, must be like the people. It ought to be so constituted, that a person, who is a stranger to the country, might be able to form a just idea of their character, by knowing that of their representatives. They are the sign—the people are the thing signified. It is absurd to speak of one thing being the representative of another, upon any other principle.

- June 21: The idea that naturally suggests itself to our minds, when we speak of representatives is, that they resemble those they represent; they should be a true picture of the people; possess the knowledge of their circumstances and their wants; sympathize in all their distresses, and be disposed to seek their true interests.

Examples of the use of this phraseology connecting Brutus and Smith are set forth below:

- Brutus 3: “those who are placed instead of the people, should possess their sentiments and feelings, and be governed by their interests, or, in other words, should bear the strongest resemblance of those in whose room they are substituted. It is obvious, that for an assembly to be a true likeness of the people of any country, they must be considerably numerous.”

- Brutus 4: “so small a number could not resemble the people, or possess their sentiments and dispositions”

- June 21: “should be the strongest resemblance to those in whose room they are substituted”

- June 21: “a true likeness”

- June 21: “just resemblance”

- June 21: “the more the Repres. resemble the people, the more likely they will be to declare their will—and the smaller the proport. of Rep. the less will be the resemb[lan]ce—the more numerous the more interested”

Brutus 1, 3, 4, 15 and 16 expressed the view that representatives should be “acquainted with” the public and its needs. Smith repeated this argument on June 21 and June 27:

- Brutus 1: “the people in general would be acquainted with very few of their rulers”

- Brutus 1: “The different parts of so extensive a country could not possibly be made acquainted with the conduct of their representatives”

- Brutus 1: “It cannot be sufficiently numerous to be acquainted with the local condition and wants of the different districts”

- Brutus 3: “acquainted with the wants and interests of this vast country”

- Brutus 4: “Those who are acquainted withthe manner of conducting business in public assemblies know how prevalent art and address are in carrying a measure”

- Brutus 15: “those who are acquainted with the costs that arise in the courts”

- Brutus 16: “Every body acquainted with public affairs knows how difficult it is to remove from office a person who is long been in it.”

- June 21: “Representation should be numerous to be acquainted with the Community and should have men of the midling Class”

- June 21: “Taxation requires men acquainted with the midling Ranks & paths of Life.”

- June 25: “A Senator will be by far the greatest part of his time from home, he will associate with none but those of his rank, and by this means he will forget the state of his constituents, be void of sympathy with them and in a considerable degree unacquainted with their true situation.”

- June 27: “It is not possible to collect a set of representatives, who are acquainted with all parts of the continent. Can you find men in Georgia who are acquainted with the situation of New-Hampshire?”

Likewise, Brutus 3 and 4 expressed the concern that representatives would be “strangers to” their constituents, which was repeated by Smith on June 25:

- Brutus 3: “The well born, and highest orders in life, as they term themselves, will be ignorant of the sentiments of the middling class of citizens, strangers to their ability, wants, and difficulties, and void of sympathy, and fellow feeling.”

- Brutus 4: “The people of this state will have very little acquaintance with those who may be chosen to represent them…. they are total strangers to”

- June 25: “by continuing long in office a man becomes a stranger to the condition and feelings of the people”

As a result of their detachment from the middling class, Brutus 3 feared that Congress would be “void of sympathy.” This concern was repeated by Smith on June 25:

- Brutus 3: “The well born, and highest orders in life, as they term themselves, will be ignorant of the sentiments of the middling class of citizens, strangers to their ability, wants, and difficulties, and void of sympathy, and fellow feeling.”

- June 25: “A Senator will be by far the greatest part of his time from home, he will associate with none but those of his rank, and by this means he will forget the state of his constituents, be void of sympathy with them and in a considerable degree unacquainted with their true situation.”

If the “substantial yeomanry” were excluded from the representation, Smith feared that Congress would not be able to “sympathize in all their distresses.” Smith argued that the “first class” would be unable to have that “sympathy with their constituents which which is necessary to connect them closely to their interest.” In 2023, Trevor Latimer proposed the “sympathy theory of representation,” which he attributes to Melancton Smith and his circle, citing to Smith’s convention speeches, Brutus and the Federal Farmer. [72B]

“radically defective”

Based on the inadequacy of the representation Brutus argued that the proposed Constitution was “radically defective.” Brutus also argued that the lack of a bill of rights rendered the Constitution “radically defective.” Brutus 3 used this identical phrase twice. Smith shared this same view and used the same phrase in Plebeian and in a speech on July 23 at the New York ratification convention.

- Brutus 3: “One man, or a few men, cannot possibly represent the feelings, opinions, and characters of a great multitude. In this respect, the new constitution is radically defective.-The house of assembly, which is intended as a representation of the people of America, will not, nor cannot, in the nature of things, be a proper one—sixty-five men cannot be found in the United States, who hold the sentiments, possess the feelings, or are acquainted with the wants and interests of this vast country.”

- Brutus 3: “the plan is radically defective in a fundamental principle, which ought to be found in every free government; to wit, a declaration of rights.”

- Plebian: “When we consider the nature and operation of government, the idea of receiving a form radically defective, under the notion of making the necessary amendments, is evidently absurd.”

- July 23: “He was as thoroughly convinced then as he ever had been, that the Constitution was radically defective”[73]

- In a newly discovered speech dated July 11 Smith called the Constitution “greatly defective.”[74]

By no means was Smith wedded to the phrase “radically defective.” For example, on June 21 he called the Constitution “defective & bad in its fundamental and radical principles that of a Representation of the people.”[75] Likewise, Brutus 1also stated that the “scheme was defective in the fundamental principles.” Brutus 3 mentioned its “principal defects.” Not surprisingly, Hamilton called the Articles of Confederation “radically defective”[76] and “defective and rotten.”[77]

free government / free republic / free state / free people

Antifederalists and Federalists alike attempted to invoke the best writers on the “science of government”[78] to support their claims, including Locke, Beccaria and Montesquieu.[79] Antifederalists in particular commonly referred to principles of the Revolution and “principles of a free government,” which they felt were threatened by the proposed Constitution.[80] For example, Brutus 16 objected that the “supreme controlling power” vested in the Supreme Court was “repugnant to the principles of a free government.”[81] On June 20 at the New York ratification convention Melancton Smith used this identical phrase – twice. Smith objected that the Three Fifths clause and the House representation formula were contrary to “the fundamental principle of a free government” and “inconsistent with every principle of a free government.[82] Melancton Smith observed on June 21 that “[a] few years ago we fought for liberty—We framed a general government on free principles.”[83]

These observations by Smith were not unusual, as the founding generation commonly attempted to ground their arguments in principles of “free government.”[84] Yet, Brutus also used the phrase “free republic” interchangeably with the phrase “free government.” Using the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, FoundersOnline, and the Rotunda Founding Era Collection it is possible to search tens of thousands of manuscripts which were not readily available to prior generations of scholars.[85] The pattern that emerges is useful attribution evidence. As will be demonstrated below, Melancton Smith and Brutus were the only founders during the ratification campaign to repeatedly use this phrase “free republic.” This is properly recognized as a distinctive Brutus / Melancton Smith fingerprint. By comparison, Federal Farmer, Publius and other colleagues never used the phrase “free republic.”

As previously discussed, Brutus and the Federal Farmer made many similar and overlapping Antifederalist arguments. This makes sense as Melancton Smith and Elbridge Gerry were both moderate Antifederalists who collaborated in New York City in September and October of 1787 before Gerry returned to Massachusetts following the Constitutional Convention. The following chart illustrates the frequency of the use of the phrase “free government,” “free republic,” “free people,” and “free state” by Brutus, Federal Farmer and Publius.

| Brutus | Federal Farmer | Publius | |

| free government | 20 | 19 | 18 |

| free people | 2 | 7 | 4 |

| free republic | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| free state | 1 (quoting Montesquieu)[86] | 2 (quoting Montesquieu and Dickinson)[87] | 0 |

Brutus, Federal Farmer and Publius regularly used the phrase “free government.” All three pseudonymous authors also used the relatively interchangeable phrase “free people.” None of the writers used the phrase “free state,” unless they were directly quoting Montesquieu or Dickinson. Brutus used the phrase “free republic” nine times and the phrase “free government” twenty times. Curiously, Federal Farmer and Publius never use the phrase “free republic,” but regularly used the phrase “free government.”

This pattern repeats across the entire DHRC. Although the phrase “free government” generates 194 hits, the phrase “free republic” only results in 11 hits. Of these 11 hits, Brutus is the first ratification era author to use the phrase, which he used repeatedly in Brutus 1, 10 and 16. Importantly, the phrase “free republic” was only used at the New York ratification convention. There is no evidence that the phrase was used at any of the other twelve state ratification conventions. The first speaker who used the phrase “free republic” was Melancton Smith on 21 June 1788.[88] The only other speaker to use the phrase was Alexander Hamilton, who immediately followed and was replying to Smith. In sum, the use of the phrase “free republic” is a telltale fingerprint of Melancton Smith and Brutus, the only author to use the uncommon phrase repeatedly, in multiple essays, and at a ratification convention.

Set forth below are the instances where Brutus uses the phrase “free republic.” In each case he could have used the similar term free government, free people, or free state.

- Brutus 1: “If respect is to be paid to the opinion of the greatest and wisest men who have ever thought or wrote on the science of government, we shall be constrained to conclude, that a free republic cannot succeed over a country of such immense extent.”

- Brutus 1: “History furnishes no example of a free republic, any thing like the extent of the United States.”

- Brutus 1: “In a free republic, although all laws are derived from the consent of the people, yet the people do not declare their consent by themselves in person, but by representatives, chosen by them, who are supposed to know the minds of their constituents, and to be possessed of integrity to declare this mind.”

- Brutus 1: “But they have always proved the destruction of liberty, and is abhorrent to the spirit of a free republic.”

- Brutus 1: “A free republic will never keep a standing army to execute its laws.”

- Brutus 1: “The confidence which the people have in their rulers, in a free republic, arises from their knowing them, from their being responsible to them for their conduct, and from the power they have of displacing them when they misbehave.”

- Brutus 1: “These are some of the reasons by which it appears, that a free republic cannot long subsist over a country of the great extent of these states.”

- Brutus 10: “He (Caesar) changed it from a free republic.“

- Brutus 16: “legislature in a free republic are chosen by the people at stated periods, and their responsibility consists, in their being amenable to the people.”

This begs the question why didn’t Federal Farmer, Publius and other founding era authors use the term “free republic” as did Brutus? One possible explanation is that some might have considered the phrase “free republic” to be redundant. By definition, in a republic power is held by the people who elect their representatives. Perhaps, Federal Farmer, Publius and others avoided the phrase “free republic” because they thought all republics were ipso facto free. If so, Federalists might have avoided the term “free republic” to avert the implication that some republics were not necessarily free.

This explanation that Federalists avoided the phrase “free republic” is consistent with the fact that the handful of writers who used the phrase “free republic” were Antifederalists. It is also likely that these Antifederalist authors were borrowing from Brutus 1. For example, Cato 3 used the phrase “free republic” twice on 25 October 1787, one week after the publication of Brutus 1 on 18 October.[89] The only other pseudonymous authors to use the unusual phrase “free republic” were An Old Whig 5 on November 1, Cincinnatus 5 on November 29 (“freest republics”), Aristides on January 31, A Farmer 2 on February 29 and A Farmer on April 16. Of course, Brutus 1, 10 and 16 used the phrase, as did Smith at the New York ratification convention.

A “complex system” with “complex powers” and a “complex form” and the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction over “law and fact” leaves “no room” for juries.

Two related Smith fingerprints involve his concern over the “complex” nature of the Constitution, which he believed would create conflict with the states. Today, we would call this complexity federalism. Yet, for Smith this complexity contained the “sure seeds of its own dissolution.” Smith was also concerned over the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction over both “law and fact,” which he felt would jeopardize the right to jury trials and leave “no room” for juries.

Brutus 6 objected to the “complex” nature of the proposed Constitution. Brutus feared among other things that the state governments would be deprived of revenue and eventually consolidated / swallowed up into the national government. Brutus then applied this reasoning to the case of revenue fearing that states would be deprived of their taxing authority. Brutus 6 concluded by presuming that “no such power is left them by this constitution.” Brutus 7 likewise described the system as “intended to be complex and not simple.”

- Brutus 6: The government then, being complex in its nature, the end it has in view is so also; and it is as necessary, that the state governments should possess the means to attain the ends expected from them, as for the general government. Neither the general government, nor the state governments, ought to be vested with all the powers proper to be exercised for promoting the ends of government. The powers are divided between them—certain ends are to be attained by the one, and other certain ends by the other; and these, taken together, include all the ends of good government. This being the case, the conclusion follows, that each should be furnished with the means, to attain the ends, to which they are designed.

- Brutus 7: It has been shewn, that no such allotment is made in this constitution, but that every source of revenue is under the controul of the Congress: it therefore follows, that if this system is intended to be a complex and not a simple, a confederate and not an entire consolidated government, it contains in it the sure seeds of its own dissolution.

These concerns over the “complex” structure of the Constitution relative to the states aligns with Smith’s convention speeches on June 27 & 30:

- June 27: part of a complex system… complex powers cannot operate peaceably together…. Because it is to form part of a complex plan – the state governments are to exist for certain local purposes… in its complex

- June 30: a complex system like ours, in which all of the objects of government were not answered by the national head, and which, therefore, ought not to possess all the means.

In newly transcribed notes of his June 30 speech, Smith referred to the Constitution as a complex system which did not reserve revenue for the states. This directly aligns with the objections raised by Brutus 6 and 7: