America’s Founding Hosts

The First Family of Hospitality (The Dalley/Fraunces/Simmons family)

Part 3 – Simmons’ Tavern

Prior to the advent of electronic communications, big city taverns and inns played an important role distributing news and information similar to the internet today. Taverns also facilitated commerce, travel and democratic engagement in their capacity as public meeting spaces. Due to its prominent location directly across from Federal Hall in New York City, Simmons’ Tavern became one of the most important locations in Manhattan when New York served as the nation’s capital from 1785 to 1790.

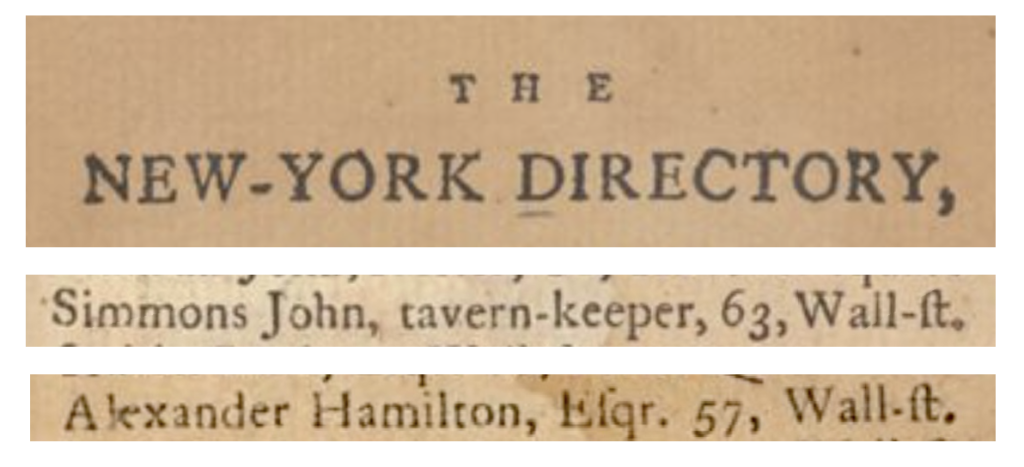

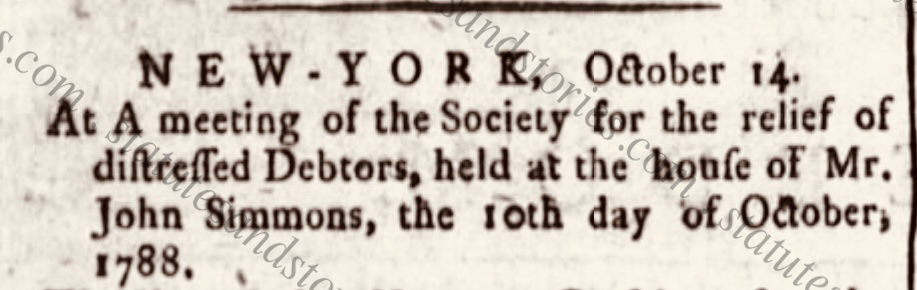

Located at 63 Wall Street on the northwest corner of Wall and Nassau Streets, Simmons’ Tavern was only doors away from Alexander Hamilton and other prominent members of the New York bar.[1] This may help explain why the New York Manumission Society was established at Simmons’ Tavern in January of 1785. Other organizations which regularly held meetings at Simmons’ Tavern included the trustees of Columbia College (formerly King’s College), the New-York Society Library[2], the Society for Relief of Distressed Debtors, and a variety of other civic organizations. Simmons’ Tavern also hosted governmental and court-related functions, including juries, grand juries, City committees and private arbitrations.

New research reveals that Simmons’ Tavern and Fraunces’ Tavern in New York formed an inter-connected network with the City Tavern and Miss Dalley’s boarding house in Philadelphia. It is thus not surprising that the proprietors of these patriotic businesses were in fact an extended family of siblings – the Dalley, Fraunces and Simmons families.

This post is the third in a multi-part series about the extended Dalley/Fraunces/Simmons family, who operated several of the most important boarding houses and taverns in the late 18th Century. America’s Founding Hosts – Part 1 discusses brother Gifford Dalley who was the doorkeeper to the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Congress when he wasn’t operating City Tavern, the Merchants’ Coffee House or Dalley’s Hotel in Philadelphia. Mary Dalley and her Philadelphia boarding house are discussed in Part 2.

Sisters Catherine and Elizabeth operated famous taverns in New York. As discussed here in Part 3 Catherine Dalley married John Simmons, who operated Simmon’s Tavern. Elizabeth Dalley married Samuel Fraunces, the proprietor of Fraunces’ Tavern. Samuel Fraunces also served as the steward of President Washington’s household in New York and Philadelphia. Fraunces’ Tavern is discussed in Founding Hosts – Part 4 (pending). Genealogical records of the Dalley/Simmons/Francis/Fraunces family and as yet unanswered questions for future researchers will be discussed in Founding Hosts – Part 5 (pending).

John Simmons and the Revolutionary War

John Simmons’ name first appears in newspaper advertisements circa 1770. He originally opened his tavern under the sign of Peter Warren, a famous British admiral.[3] It is unclear how long Simmons marketed his tavern using Warren’s name. Prior to the Revolutionary War Simmons’ Tavern periodically hosted meetings of the “Common Council” of the City of New York, the City’s governing body consisting of the mayor and city aldermen. The minutes of the Common Council in the 1770s refer to John Simmons as an “innkeeper” and “innholder,” which were used interchangeably.[4] As the City of New York reimbursed Simmons for the cost of “liquor,” it is clear that alcohol was served in his “house,” even during grand jury proceedings.[5]

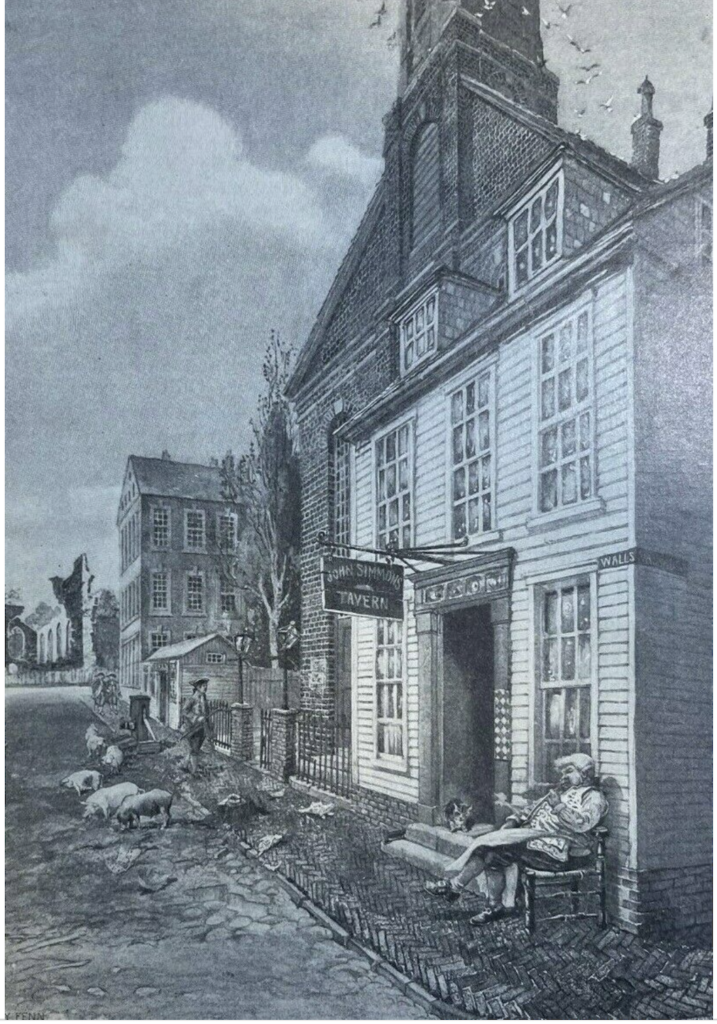

Pictured below is Simmons ‘Tavern on Wall Street in 1784, as imagined by Henry Fenn, appearing in Harper’s Magazine in July, 1908

Pictured above is Wall Street in 1789, with Simmons’ Tavern visible between the First Presbyterian Church and the newly redesigned Federal Hall

After the Revolutionary War Simmons’ Tavern “witnessed the formalities which gave birth to the new American city of New York” when James Duane was sworn in and installed as mayor at Simmons’ Tavern in February of 1784.[6] The tavern would continue operating for more than a decade after the Revolutionary War, including during formative periods in the history of New York and the new Federal government.

Although John Simmons was born in England[7], in 1776 he briefly served in the American “2d Regt. of the New York Troops Commanded by Colonel James Clinton”, a private volunteer militia.[8] Before the British captured New York City, John Simmons and his brother-in-law, Gifford Dalley, were given leave by the New York Provincial Congress to meet with Captain George Vandeput of the HMS Asia. The British warship had fired its cannons “damaging the upper part of several houses” in Manhattan on 23 August 1775.[9] The skirmish occurred during the “Raid on the Battery,” New York’s first military engagement of the Revolutionary War.[10]

The New York Provincial Congress authorized the raid on Fort George on 22 August 1775, which recovered almost two dozen cannons from the “Grand Battery” at the southern tip of Manhattan.[11] While details are sparse, it is reasonable to assume that Simmons and Dalley, the American representatives selected to meet with Captain Vandeput, were trusted members of the community. There is no doubt that the two brothers-in-law knew each other, as Catherine Dalley married John Simmons in 1758.[12] It is unclear why Samuel Fraunces was not selected to meet with Vandeput, as Fraunces’ Tavern was damaged by the British cannon fire.[13] Interestingly, a young Alexander Hamilton is also connected to the event. Hamilton was a member of the raiding party which seized twenty-one cannons while under fire from the HMS Asia.[14]

A year later the British captured Manhattan in the Battle of Long Island.[15] The British would hold the strategic port city from September of 1776 until Evacuation Day in November of 1783. During the British occupation of Manhattan, loyalists flooded into the city while those supporting the Revolutionary cause fled. Although there is no direct evidence when John Simmons and his family left New York City, “indirect evidence makes clear that they must have fled when, or soon after, the British arrived and they did not return until the fighting was over.”[16] The Simmons family spent at least part of the war years in Philadelphia, which is further evidence of the close connections between the Simmons and Dalley families, which also relocated to Philadelphia.[17]

Reopening of Simmons’ Tavern and City Hall after the War

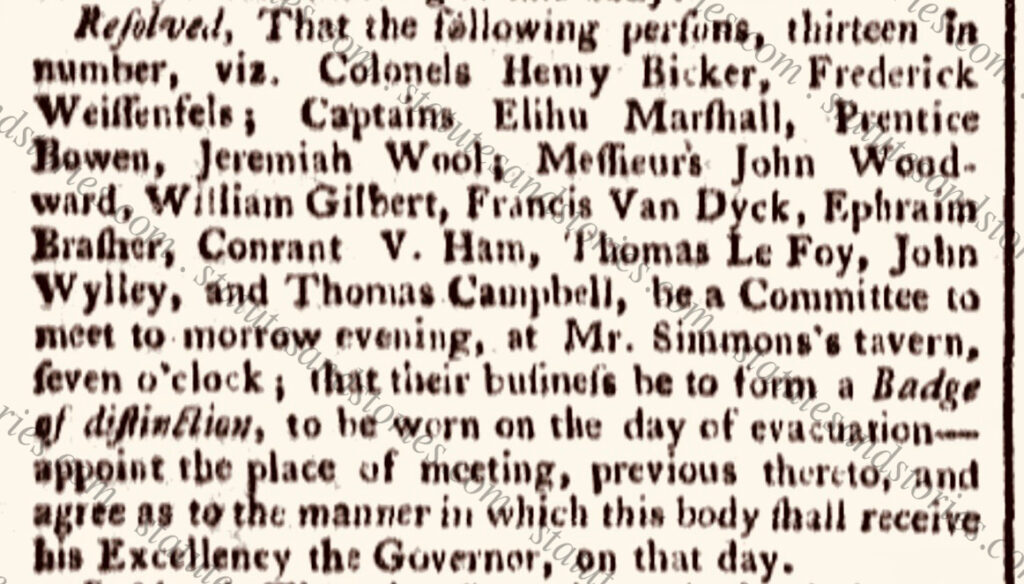

Pursuant to the Treaty of Paris which ended the Revolutionary War, the British departed New York City on 25 November 1783, celebrated for many years as “Evacuation Day.” It was said that General Washington attended an Evacuation Day banquet held at the Simmons’ Tavern on the evening of November 25.[18]Consistent with this claim, newspaper reports confirm that a committee of prominent New Yorkers met at Simmons’ Tavern on 19 November 1783 to plan security and the protocol to receive Governor George Clinton and General Washington. After triumphantly leading the victorious Continental troops parading down Broadway on Evacuation Day,[19] Washington also dined at Fraunces’ Tavern.[20] Three months later James Duane was installed as New York City’s first Mayor post-independence on 9 February 1784.[21]

After Mayor Duane was sworn into office, the New York City Common Council continued meeting at Simmons’ Tavern through March 30, 1784, while City Hall was being repaired following the British occupation.[22] It has been suggested that the tavern was selected as the temporary replacement for City Hall due to the popularity of its owner, who has been described as a “fixture on Wall Street.”[23] The fact that Simmons’ Tavern was conveniently located across the street from City Hall no doubt also played a role in its selection.

By 1788, New York City contained 330 licensed taverns. Yet, Simmons’ Tavern was “one of the city’s most popular establishments and its owner one of the city’s most prominent tavern keepers.”[24] For example, John Simmons appears in Washington Irving’s letters to James Brevoort.[25] The minutes of the New York City Common Council provide abundant examples of meetings, hearings and related court functions held at Simmons’ Tavern before and after the war.[26]

The Common Council periodically held meetings at Simmons’ Tavern until the British captured New York City in 1776.[27] Examples of official City meetings held at Simmons’ Tavern include jury proceedings inquiring into the death of Mary Murphy in August of 1773[28] and committee meetings involving city water supplies, wells and pumps in 1775.[29] Activity at Simmons’ Tavern resumed after the War, beginning in February of 1784. City records reflect payments for “public dinners” to celebrate American Independence on July 4th and Evacuation Day on November 25th.[30]

Alexander Hamilton and Simmons’ Tavern

It is not unreasonable to ask whether Simmons’ Tavern could be described as Alexander Hamilton’s neighborhood tavern? According to the first New York street directory published in 1786, Hamilton resided at 57 Wall Street while Simmons’ Tavern was located at 63 Wall Street.[31] As far as can be determined, Hamilton never singled out Simmons’ Tavern as his favorite watering hole. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that Hamilton regularly walked through its doors, as did other prominent New Yorkers.

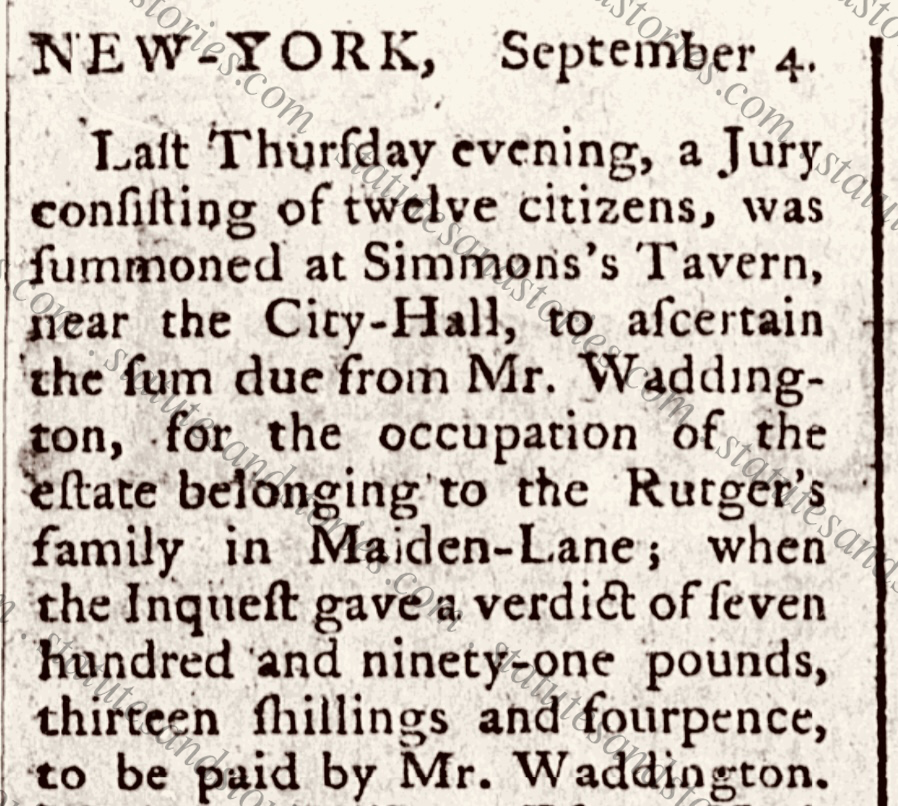

Rutgers v. Waddington was arguably Alexander Hamilton’s most famous legal case. Hamilton’s client, loyalist Joshua Waddington, was sued for rent accruing during the British occupation of New York City. Among other defenses, Hamilton claimed that Waddington had paid rent to the British authorities. Mayor Duane, one of the judges, delivered the Court’s decision on August 17, 1784. Duane held that Waddington was only liable for rent during the period when the building was under civilian control (September 1778 to April 1780), but not when rent was paid under order of the British military command (May 1780 to March 1783). After the Court’s decision a jury was required to calculate damages. The jury met in Simmons’ Tavern, where it awarded less than 1/10 of what Rutgers sought. Over his career, Hamilton argued more than 40 other “Trespass Act” cases, until the punitive law was repealed in 1787.[32]

Importantly, Rutgers was an early case establishing the principle that state law is void if it conflicts with federal law (or a U.S. treaty). Hamilton successfully argued that New York’s Trespass Act violated both the law of nations and the Treaty of Paris, which had been ratified by Congress. In so holding the Rutgers case created an important state court precedent for judicial review. Hamilton advanced his same arguments from the Rutgers case in Federalist 22 and 78. According to Hamilton, the “interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the Courts” and in the case of conflict “the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute.” [33] In 1803 Chief Justice Marshall agreed in the seminal case of Marbury v. Madison.

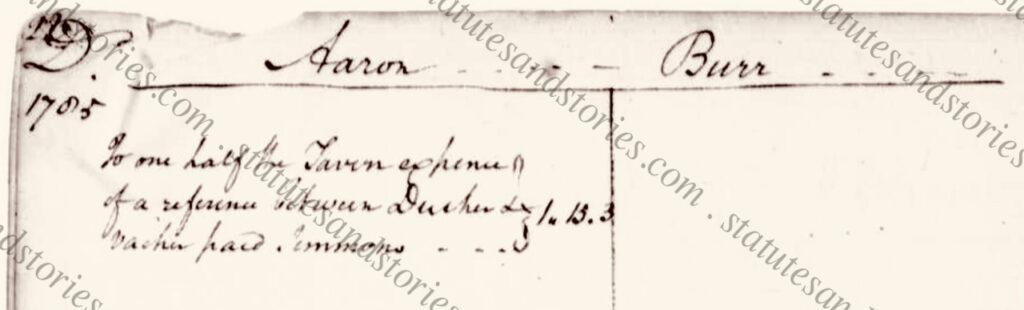

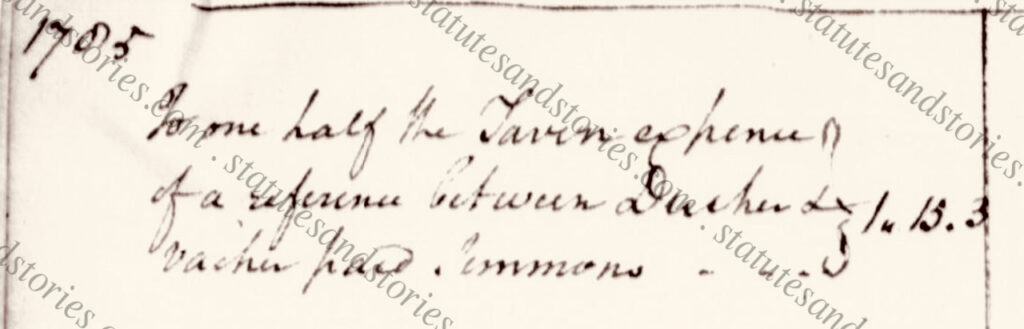

Alexander Hamilton’s “cash book” also illustrates his connection with Simmons’ Tavern.[34] In 1785 Hamilton and Aaron Burr split the cost for a “reference” held at Simmons’ Tavern. While the term is no longer used today, a reference was a referral to private arbitrators (“referees”) ordered by a court, or mutually agreed by litigants. References were commonly held in Simmons’ Tavern due to its location near City Hall.[35] Creditor meetings for insolvent debtors and probate estates were also frequently held at Simmon’s Tavern.[36] In many respects, Simmons’ Tavern served as an informal satellite courthouse. This helps explain why an ad in the New-York Morning Post claimed that Simmons’ Tavern was “frequented by Gentlemen of the law.”[37]

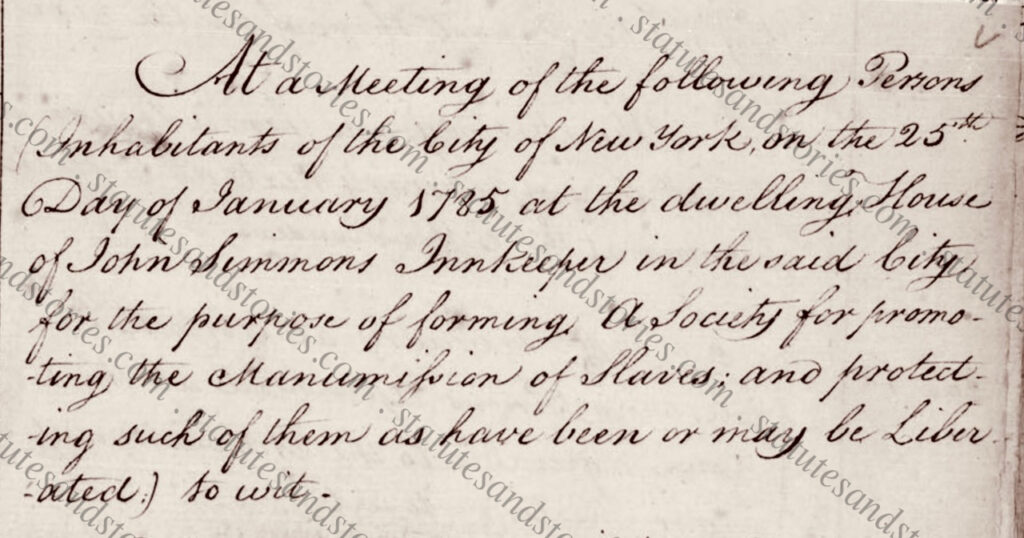

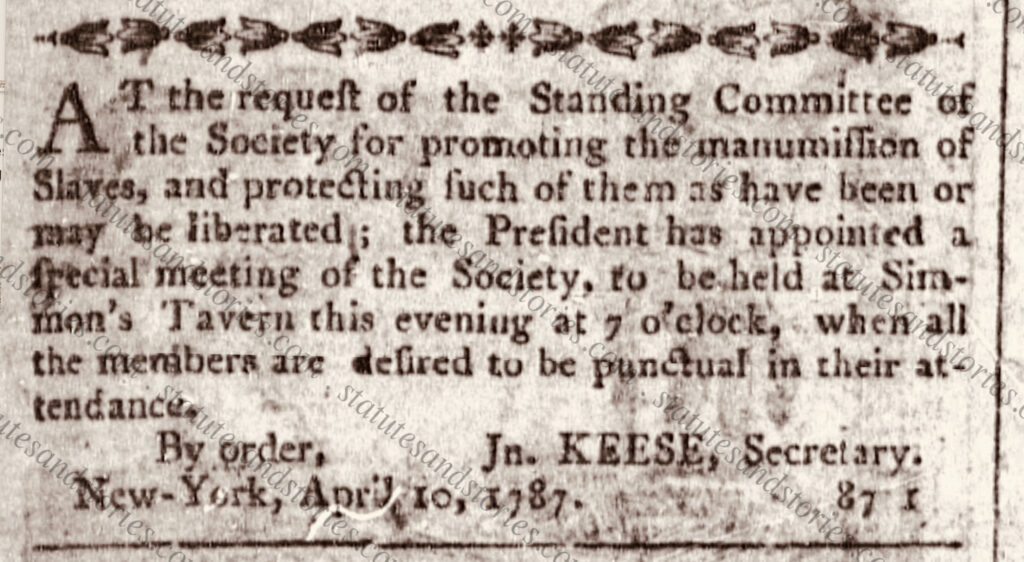

Perhaps the most consequential meeting held at Simmons’ Tavern was the establishment of the New York Manumission Society on 25 January 1785.[38] The Manumission Society met quarterly at Simmons’ Tavern for many years, including in April of 1787, the month before the Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia.

Other Meetings at Simmons’ Tavern

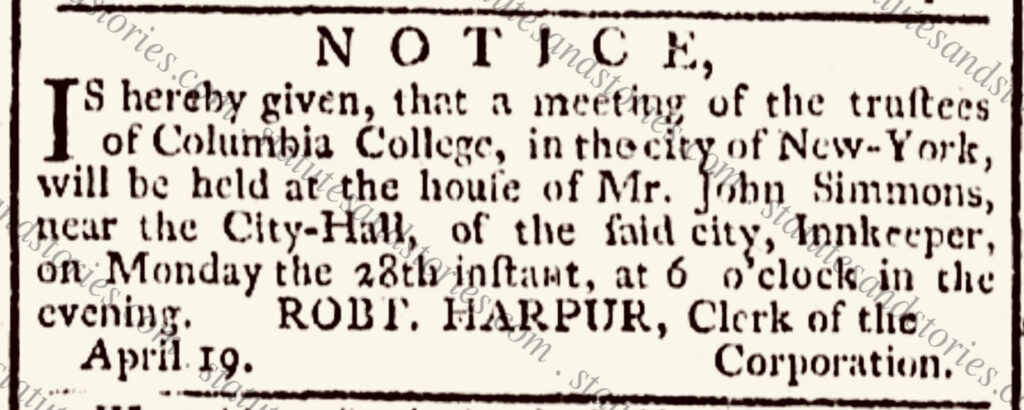

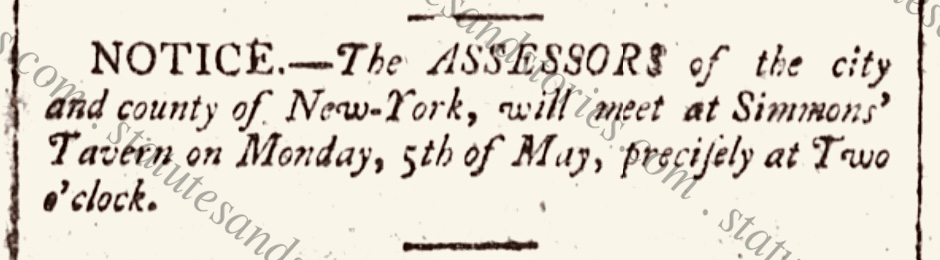

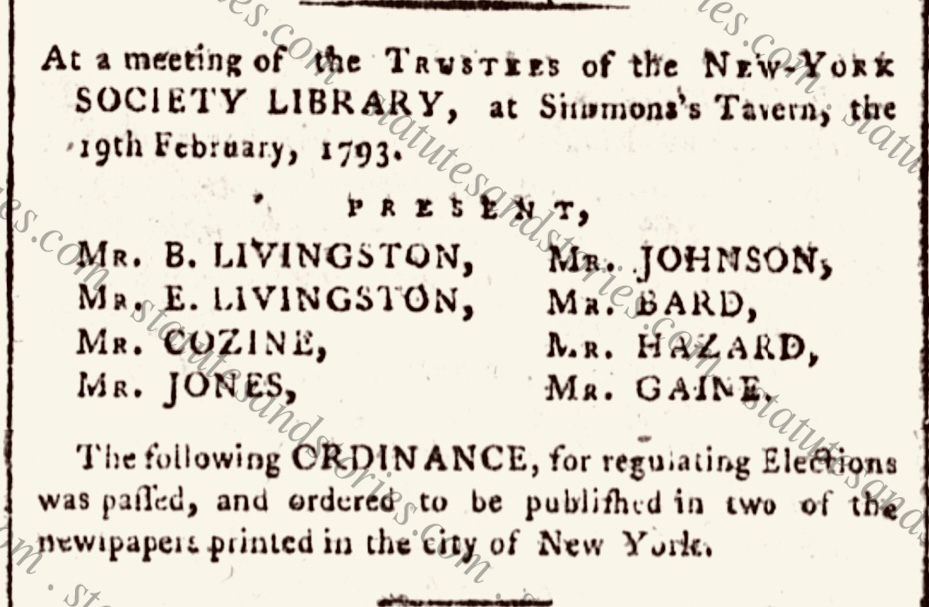

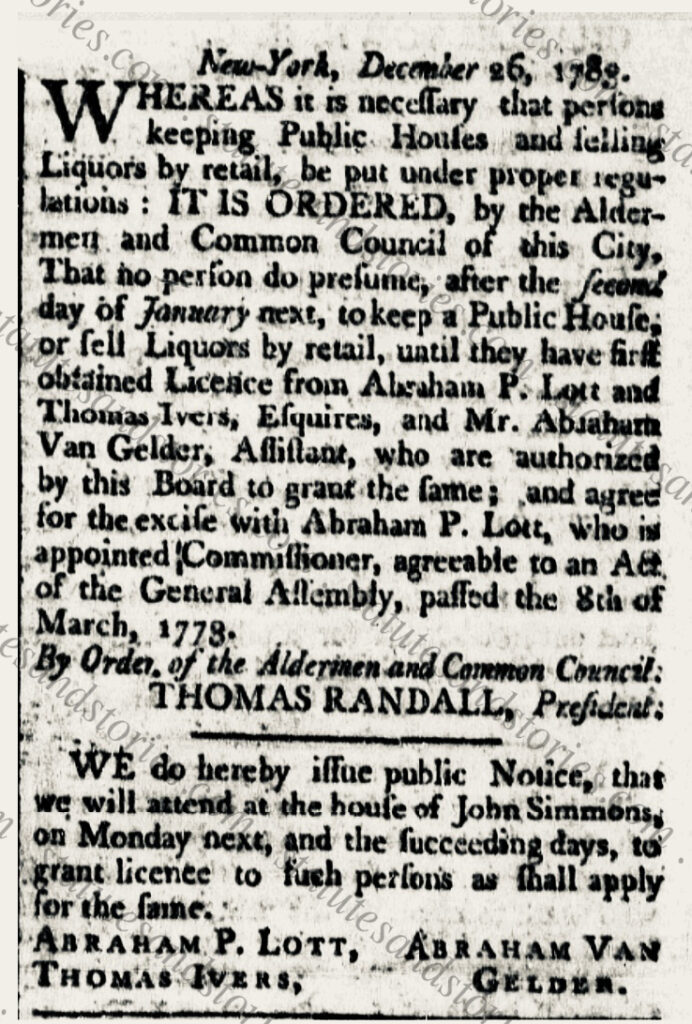

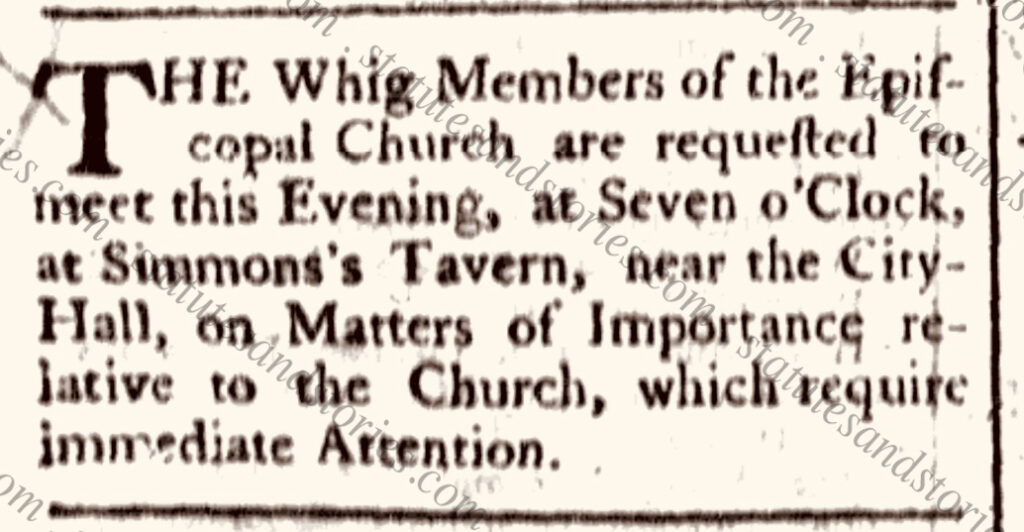

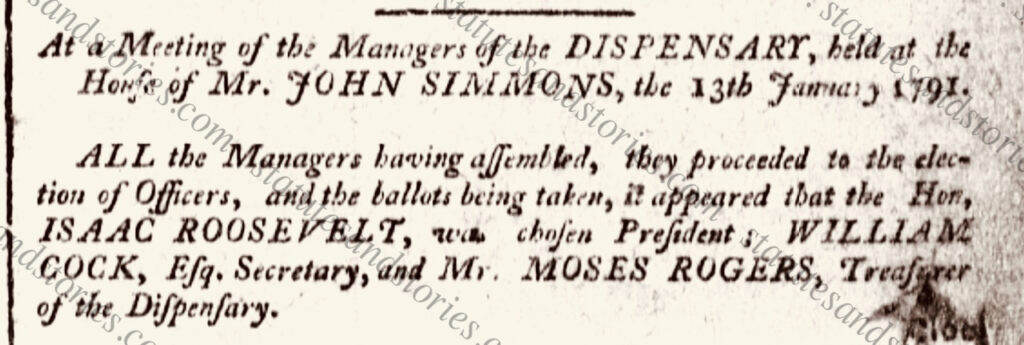

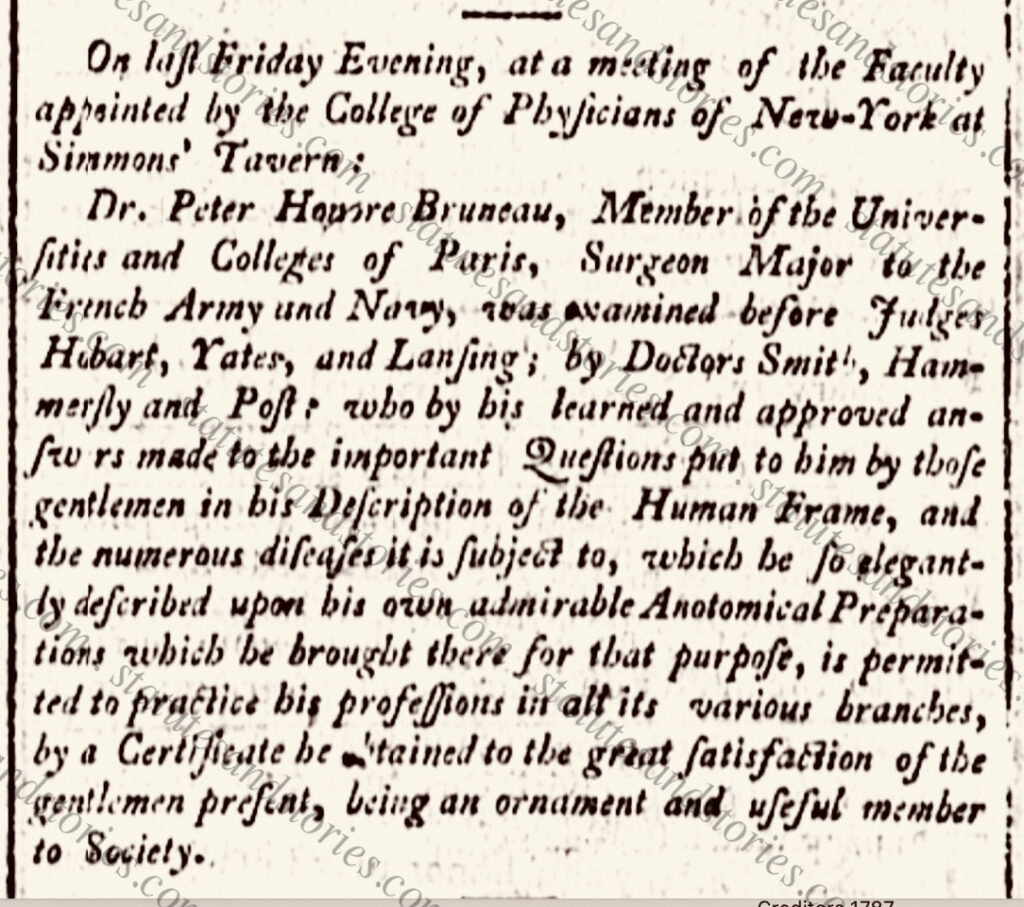

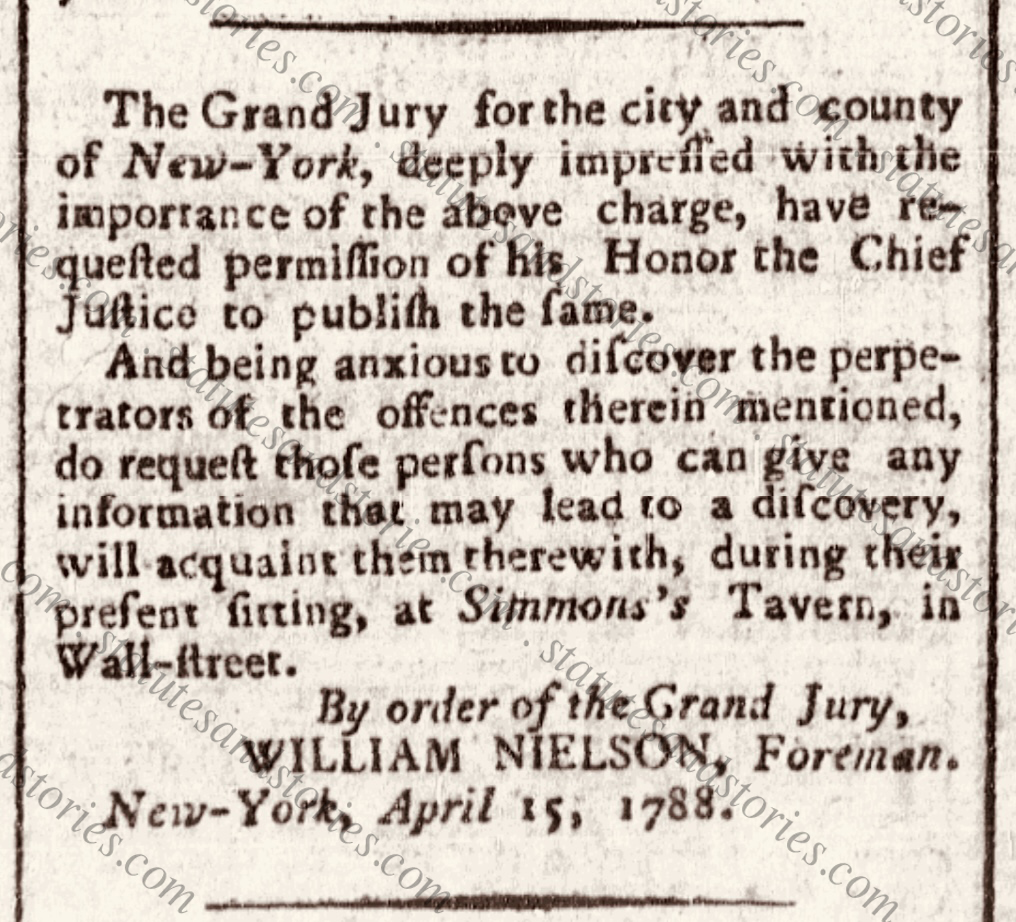

Other civic and business meetings held at Simmons’ Tavern were decidedly more mundane. From 1784 until John Simmons’ death in 1795 an enormous variety of meetings took place at Simmons’ Tavern. Copied below, in no particular order, are a sample of newspaper advertisements and legal notices evidencing the activity at Simmons’ Tavern:

- meetings of the trustees of Columbia College

- meetings of the tax assessors for the City of New-York

- a meeting of the Regents of University of the State of New-York on 2 Aug 1790[39]

- meetings of the trustees of the New-York Society Library

- meetings for the Society for Relief of Distressed Debtors

- a meeting of the Alderman and Common Council of the City of New -York to award liquor licenses for public houses in 1784

- meetings of the Whig Members of the Episcopal Church in 1783

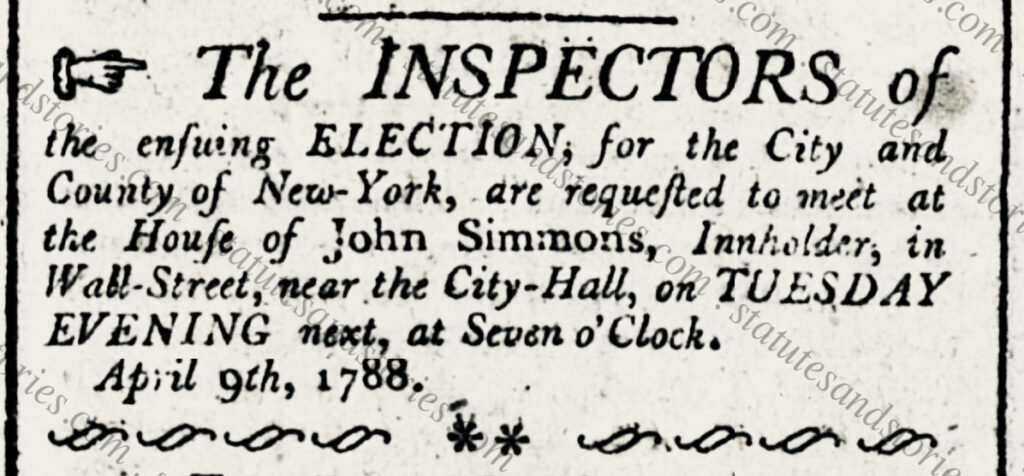

- meetings of the “Inspectors of the ensuing ELECTION” in 1788 (the New York Ratification Convention)

- meetings of the managers of the Dispensary in 1791

- a meeting of the faculty of the College of Physicians of New-York in April of 1794

- and a host of court-related proceedings

Not surprisingly, Simmons’ Tavern played a role in the ratification of the Constitution in New York. Election inspectors for the election of delegates to the New York Ratification Convention met at Simmons’ Tavern in April of 1788. [39a]

In 1789 Simmons’ Tavern was used as temporary quarters for City Hall when the newly re-named Federal Hall was being remodeled/renovated for the new federal Congress.[40] Simmons’ Tavern served this same function in 1784 when City Hall was renovated after the British evacuated New York. The newly created federal government’s first capital was briefly located in New York City beginning in March of 1789, until Congress relocated to Philadelphia in December of 1790.

After John Simmons’ death in 1795 Catherine Simmons continued to operate Simmons’ Tavern.[41] She would later relocate to Washington, D.C. where she lived with her eldest son, William, until her death in 1818.[42] William was a successful clerk who worked in Alexander Hamilton’s Treasury Department before being appointed by President Washington as accountant for the War Department in 1795.[43] Another Simmons son, Stephen, entered into the military. Stephen was appointed as a regimental pay master by Major General Alexander Hamilton in October of 1799, confirming the close connection between Hamilton and the Simmons extended family.[44] Stephen’s sad tale is told in the book, A Hanging in Detroit.[45]

This post continues in Part IV (pending) which will discuss sister Elizabeth Dalley Frances (Fraunces’ Tavern). Genealogical records of the Dalley / Simmons / Francis / Fraunces family and as yet unanswered questions for future researchers will be discussed in Part V (pending).

Endnotes

[1] As described in the New-York Moring Post and Daily Advertiser on 27 February 1788, Simmons’ Tavern was “frequented by Gentlemen of the law” and “contiguous to City-Hall.” David Frank’s The New-York Directory (1786) lists the following addresses for members of the New York Bar: Alexander Hamilton (57 Wall Street); future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brockholst Livingston (12 Wall Street); Hamilton’s good friend, attorney Robert Troup (67 Wall Street); Judge Robert Morris (1 Wall Street); William Livingston (52 Wall Street); Daniel C. Verplanck (3 Wall Street); William Cock (66 Wall Street); Thomas Smith (9 Wall Street); John Lawrence (13 Wall Street).

[2] The New-York Society Library is the oldest library in New York, established in 1754. https://www.nysoclib.org

[3] New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, 8 Oct. 1770; Robert H. Dodd, The Iconography of Manhattan Island (1922), 614, 814. According to Dodd, the “Sign of Sir Peter Warren,” was the old name of Brock’s Tavern which was located across the street. By doing so Simmons was presumably attempting to attrack Brock’s former clientele.

[4] Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York:1675-1776 (1905), VIII:98, 103.

[5] Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York:1675-1776 (1905), VII:440

[6] W. Harrison Bayles, Old Taverns of New York (1915), 341.

[7] John Simmons was born in Cuckfield, Sussex, England. According to his will he owned property in England located “in Hanover Row, Portsmouth Common, England.” Chardavoyne, 9.

[8] Chardavoyne, n. 20 at 10, citing Frederic G. Mather, The Refuges of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut (1913), 1017.

[9] Peter Force, American Archives: A Collection of Authentic Records, State Papers, Debates, and Letters and other Notices of Public Affairs (December 1840), III:238, 260.

[10] Michael E. Newton, Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years (2015), 131; Paul R. Wonning, Time Line of the American Revolution – 1775: A Journal of the War of Independence (2019), 233; New York Almanac, “August 23, 1775”.

https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/2022/08/august-23-1775-the-british-bombard-the-city-of-new-york/

[11] Force, 260. The story of the Raid on the Battery is also recounted in several newspaper reports, including The New York Gazette, 28 August 1775 and The Pennsylvania Evening Post, 29 August 1775.

[12] In 1758 Simmons and Dalley became brother-in-laws when Catherine Dalley Salter married John Simmons. Catherine was born in Perth Amboy, Middlesex County, New Jersey in approximately 1741. She married John Simmons on 28 December 1758 at Trinity Church in New York City. This was Catherine’s second marriage after her first husband, Dr. William Salter, passed away after less than two years. According to Trinity Church records, Catherine Dalley and William Salter were married on 4 September 1756. “Earliest Trinity Church Marriages,” The New York Genealogical & Biographical Record 19 (October, 1888), XIX:147, 149. Catherine spent her last years living with her eldest son William Simmons. She died at William’s home in Washington, D.C., on 15 July 1818 at age 76.

[13] It is possible that Gifford Dalley was selected as the representative for Fraunces’ Tavern, as Gifford’s sister Elizabeth was married to Samuel Fraunces, the owner of Fraunces’ Tavern. According to contemporaneous accounts, “a house next to Roger Morris’s and Samuel Francis’s, as the corner of the Exchange, each had an eighteen-pound ball shot into their roofs….” Force, 259. It is possible that Gifford Dalley was selected as the representative for Fraunces’ Tavern, as Gifford’s sister Elizabeth was married to Samuel Fraunces, the owner of Fraunces’ Tavern. One can also conjecture that Gifford may have been employed by Samuel Fraunces or trained by him.

[14] Newton, 130-331. As described by Alexander Hamilton’s son, “Hamilton was present at this exciting scene, and was thus associated, in the minds of the people, with the first act of resistance to the first act of violence offered to the province.” John Church Hamilton, History of the Republic as Traced in the Writings of Alexander Hamilton and of his Contemporaries (1857), 1:99.

[15] The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn, was fought on 27 August 1776. John J. Gallagher, The Battle of Brooklyn: 1776 (1995), ix.

[16] David Chardavoyne reasons that it is unlikely that the patriots would have met at Simmons’ Tavern to make sensitive plans relating to the British evacuation if its owner had remained in New York City during the British occupation. Chardavoyne, 10.

[17] Stephen Gifford Simmons, the youngest son of John and Catherine Simmons, was baptized in Philadelphia’s Christ Church on 3 February 1780. Chardavoyne, 11 citing Archives of Christ Church, “Baptismal Record 1769-1794,” 953. Sister Mary Dalley and brother Gifford Dalley also show up in Philadelphia, as evidenced by multiple primary sources. By the late 1770s Mary Dalley is operating her boarding house in Philadelphia. Gifford Dalley takes over the operation of City Tavern following the British evacuation of Philadelphia.

[18] Henry Collins Brown, Glimpses of Old New York (1917), 54; Oswald Garrison Villard, “The Early History of Wall Street” in Historic New York (1897), Ed. Maud Wilder Goodwin, 107; David G. Chardavoyne, A Hanging in Detroit: Stephen Gifford Simmons and the Last Execution under Michigan Law (2003), 11; Fredrick Trevor Hill, The Story of a Street: A Narrative History of Wall Street from 1644 to 1908 (1908), 88.

[19] The scene is imagined in the 1879 painting “Evacuation Day and Washington’s Triumphal Entry” by Edmund P. Restein.

[20] W. Harrison Bayles, Old Taverns of New York (1915), 315. There is solid evidence that Washington dined at Fraunces’ Tavern. While it is possible that contemporary accounts confused the two taverns, it is also possible that Washington attended celebrations at both Fraunces’ Tavern and Simmons’ Tavern on Evacuation Day. As discussed in Part

[21] Hill, 87-88; Bayles, 340. Duane was installed at special meeting of the City Council, having been appointed by Governor George Clinton and the Board of Appointment. He took the oath of office in the presence of Governor Clinton and the Lieutenant Governor.

[22] City Hall had been used by the British as a prison during the war. Wall & Nassau: An Account of the Inauguration of George Washington, Henry Collins Brown and M. R. Werner (1939), 41; Hill, 88.

[23] Michael & Ariane Batterberry, On the Town in New York: The Landmark History of Eating, Drinking and Entertainments from the American Revolution to the Food Revolution (1999), 20.

[24] Chardavoyne, 8-9.

[25] Letters of Washington Irving to Henry Brevoort, Ed. George S. Hellman (1918 edition), 26; Brown, 54.

[26] Common Council periodically met at Simmons’ Tavern after the War. The minutes reflect meetings/functions at Simmons’ Tavern on the following dates: 17 September 1785, 9 July 1788, 7 January 1789, 12 October 1789, 10 September 1790, 2 July 1792, 23 July 1792, and 21 July 1793.

[27] The Common Council minutes reflect meetings at Simmons’ Tavern in April of 1774, July of 1775, September of 1775, and January of 1776.

[28] Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York:1675-1776 (1905), VII:440.

[29] The New-York Journal, 9 February 1775; Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York:1675-1776(1905), VIII:105.

[30] Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York: 1784-1831 (1917), I:732 & 764.

[31] Frank’s The New-York Directory, 47, 63.

[32] Julius Goebel, The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton (1964), I:310. The Trespass Act was repealed in 1787 pursuant to a bill introduced by New York Assemblyman Alexander Hamilton. Richard Brookhiser, Alexander Hamilton: American (2000), 59.

[33] https://history.nycourts.gov/case/rutgers-v-waddington/

[34] https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0007

[35] Julius Goebel, The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton (1969), II:376, 380.

[36] For examples of creditor meetings held at Simmons’ Tavern included: New York Daily Advertiser, 8 January 1787; New-York Daily Gazette, 15 December 1792; New York Daily Advertiser, 3 September 1793.

[37] New-York Morning Post & Daily Advertiser, 27 February 1788.

[38] https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-04-02-0013

[39] Bayles, 341.

[39a] John P. Kaminski, ed., Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (2005), 21:1494-1495.

[40] Hill, 88.

[41] Bayles, 341; Greenleaf’s New Daily Advertiser, 5 August 1796.

[42] http://tdpgenealogyblod.blogspot.com/2016/02/the-dally-family.html

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Dally-326#_note-2

[43] https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-18-02-0201

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-08-02-0066

[44] https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/02-01-02-1455

[45] David G. Chardavoyne, A Hanging in Detroit: Stephen Gifford Simmons and the Last Execution under Michigan Law (2003).