America’s Founding Hosts

The First Family of Hospitality (The Dalley/Fraunces/Simmons family)

Part 1 – Gifford Dalley

Historians have long recognized the central role played by taverns and boarding houses during formative periods in American history. In particular, delegates to the Continental Congress and Constitutional Convention were very familiar with City Tavern and Miss Dalley’s boarding house in Philadelphia. Fraunce’s Tavern and Simmon’s Tavern similarly played an important civic function in New York. New research reveals that these establishments formed an inter-connected network catering to the founding generation. It is thus not surprising that the proprietors of these patriotic businesses were in fact an extended family of siblings – the Dalley, Fraunces and Simmons families.

At various times from the late 1770s through the 1790s Gifford Dalley[1] operated City Tavern, the Merchant’s Coffee House, and Dally’s Hotel in Philadelphia.[2] His sister, Mary Dalley, operated a long-overlooked boarding house whose residents included Samuel Adams, Elbridge Gerry, Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris.[3]

Two other Dalley siblings, Elizabeth and Catherine, would have been well known in New York. Elizabeth Dalley married Samuel Fraunces, the proprietor of Fraunce’s Tavern famously located at 54 Pearl Street in Manhattan.[4] Sister Catherine Dalley married John Simmons, who operated Simmon’s Tavern located at 63 Wall Street near City Hall in Manhattan.[5] Recognizing its importance, City Tavern was reconstructed by the Park Service in connection with America’s bicentennial in 1976.

In an age before electronic communications, taverns provided a mechanism to share breaking news, conduct business and exchange political views in an emerging democracy. Taverns were a focal point for “political discussion, for social clubs, and for meetings of all kinds.”[6] They also served as transportation hubs which were “key nodes in Atlantic networks of communication.”[7] It is no accident that stage coaches between New York and Philadelphia regularly departed from the “stage-office” located across from City Tavern.[8] Tickets and schedules for stage coaches and packet boats were available at the stage office (or designated boarding houses), depending on the particular stage line.

Gifford Dalley’s Hospitality Ventures

Operating a tavern in the 18th century was a fickle line of work, as remains the case today. “Newspaper advertisements from the period demonstrate that tavernkeepers frequently switched locations, hung out different signs, started businesses and failed, converted public houses into dwellings, and vice versa.”[9] As illustrated below, this was particularly true for Gifford Dalley who operated taverns from three separate locations between 1778 to 1798.

Gifford Dalley appears to have been born around 1742 in Middlesex County, New Jersey.[10] During the Revolutionary War he served as a quartermaster in the New Jersey militia and was selected as the doorman for Congress in 1789, a job he would hold during the First, Second and Third Congress from 1789 to 1795. The doorkeeper was elected at the beginning of each Congressional session and was responsible for managing the chambers and maintaining order. When the First Congress relocated from New York to Philadelphia in 1790 Gifford moved with the federal government. Gifford likely played a logistical role, having operated City Tavern after the British departure from Philadelphia.

When Philadelphia’s famous City Tavern initially opened in 1773-1774 it was considered the finest boarding house of its kind in America. It was furnished “in style of the best London taverns.”[11] As described by John Adams, City Tavern was “the most genteel” tavern in America.[12] Designed with “several large club-rooms, two of which could be thrown together to make a large dining-room, fifty feet long.”[13] For many years City Tavern was “the most important public house in the most important city in British North America.”[14]

During the Revolutionary War the British captured Philadelphia in September of 1777 forcing Congress to flee America’s largest city. The nine-month occupation of Philadelphia ended in June of 1778 enabling Congress to return home. After General Howe’s departure, City Tavern was a shell of its former self. The owners of City Tavern retained Gifford Dalley to replace the former proprietor, Daniel Smith, a Tory who left the City with the British and 3,000 other loyalists.[15]

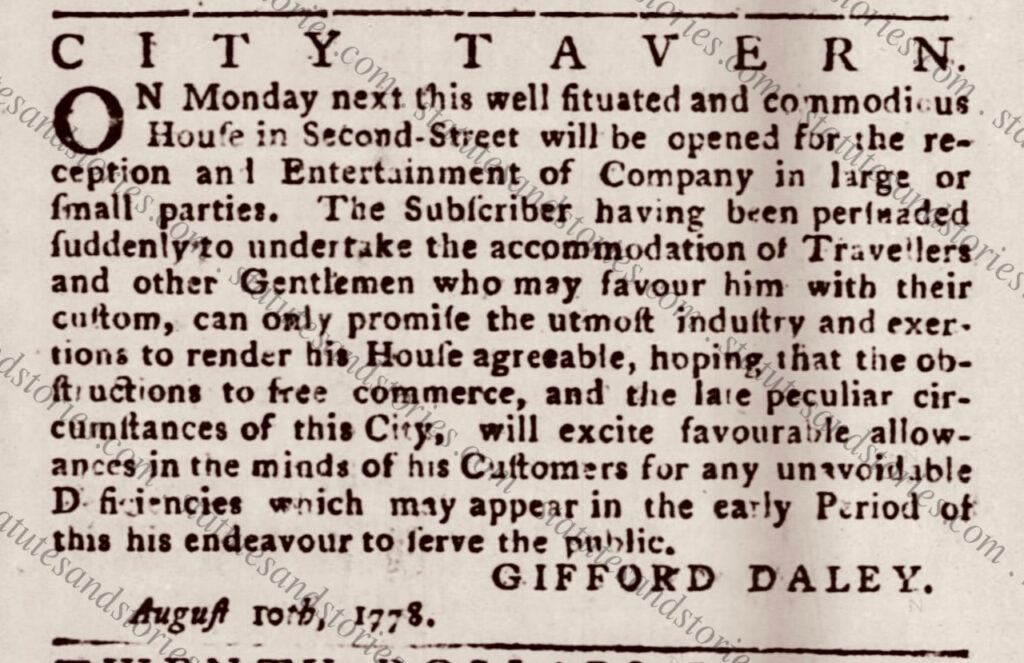

Gifford Dalley reopened the City Tavern in August of 1778 following the British departure from Philadelphia.[16] According to Gifford he was persuaded “suddenly to undertake accommodation of travelers.” He promised to provide “the utmost industry and exertions” hoping that the “obstructions to free commerce and the late peculiar circumstances of this City” would excuse any “unavoidable deficiencies.”

Before opening his doors to the public Dalley celebrated Congress’ return to the city from exile with a “decent entertainment” on July 4th.[17]

The entertainment was elegant and well conducted. There were four tables spread, two of them extended the whole length of the room, the other two crossed them at right angles. At the end of the room opposite the upper table was erected an orchestra…As soon as the dinner began, the music consisting of clarinets, haut-boys, French horns, violins and bass violins…Then the toasts followed each by a discharge of fieldpieces, were drank and so the afternoon ended. In the evening there was a cold collation and a brilliant exhibition of fireworks.[18]

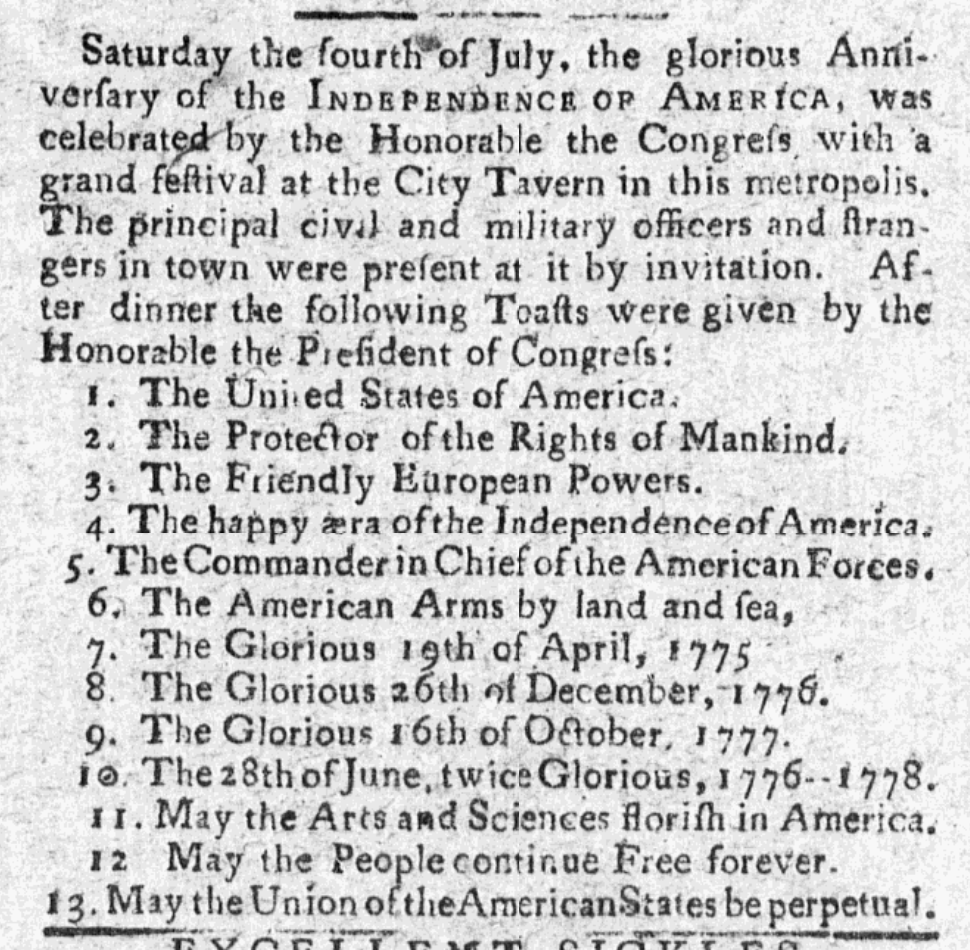

The thirteen toasts given on July 4, 1778 at City Tavern are listed below, as widely reported in newspapers around the nation. Attendees included the Honorable Congress and the principal civil and military officers. The toasts were led by Henry Laurens, the President of Congress in 1778.

The celebration with Congress at City Tavern was followed by other formal galas. On July 22 Dalley hosted “an elegant entertainment” provided by army officers and gentlemen of the city “to the young ladies who had manifested their attachment to the cause of virtue and freedom, by sacrificing every convenience to the love of their country.”[19] Shortly thereafter, Dalley catered French Minister Plenipotentiary Conrad Alexander Gerard’s reception by Congress on 6 August 1778.[20] “Nothing was spared in making this ‘entertainment’ suitable to the great event, signifying recognition of America by the world’s greatest power.”[21] Gerard responded with a “grand entertainment” of his own at City Tavern on 25 August 1778, on the occasion of the birthday of “His Most Christian Majesty Louis the Sixteenth.” Pennsylvania Packet, 27 August 1778.

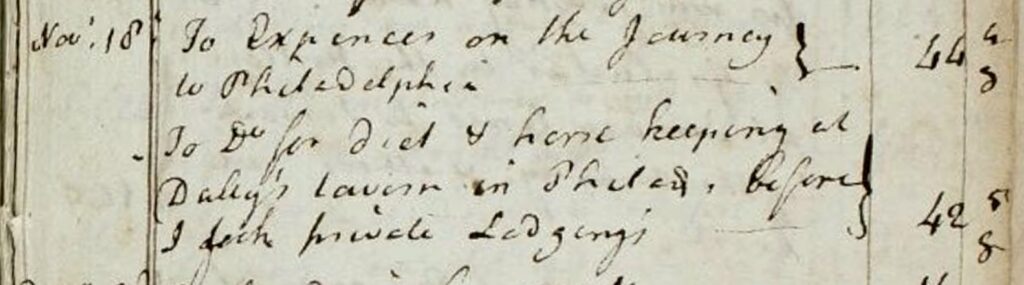

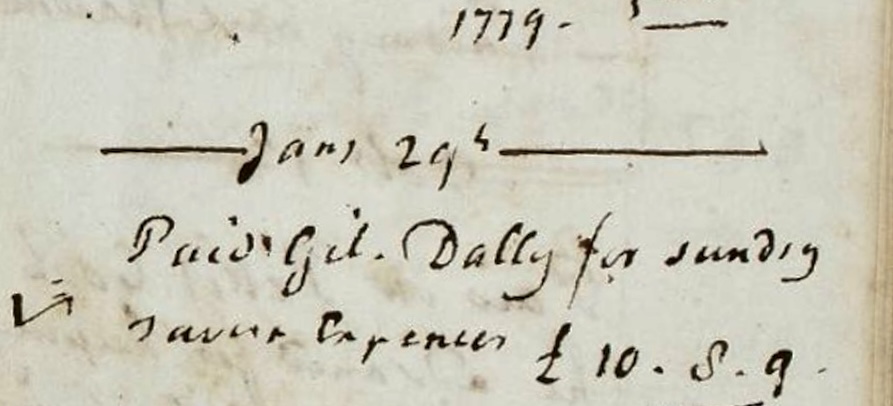

While operating City Tavern, Dalley catered to patriots in Philadelphia during the war. For example, the General Assembly of the State of Pennsylvania paid Dalley to host a “dinner for 270 gent” on 1 December 1778.[22] John Jay was a guest at City Tavern when elected President of the Continental Congress on 10 December 1778.[23] Pictured above are sample expenses paid by New York Congressional delegate James Duane to Gifford Dalley for room and/or board at City Tavern in November of 1778 and January of 1779.

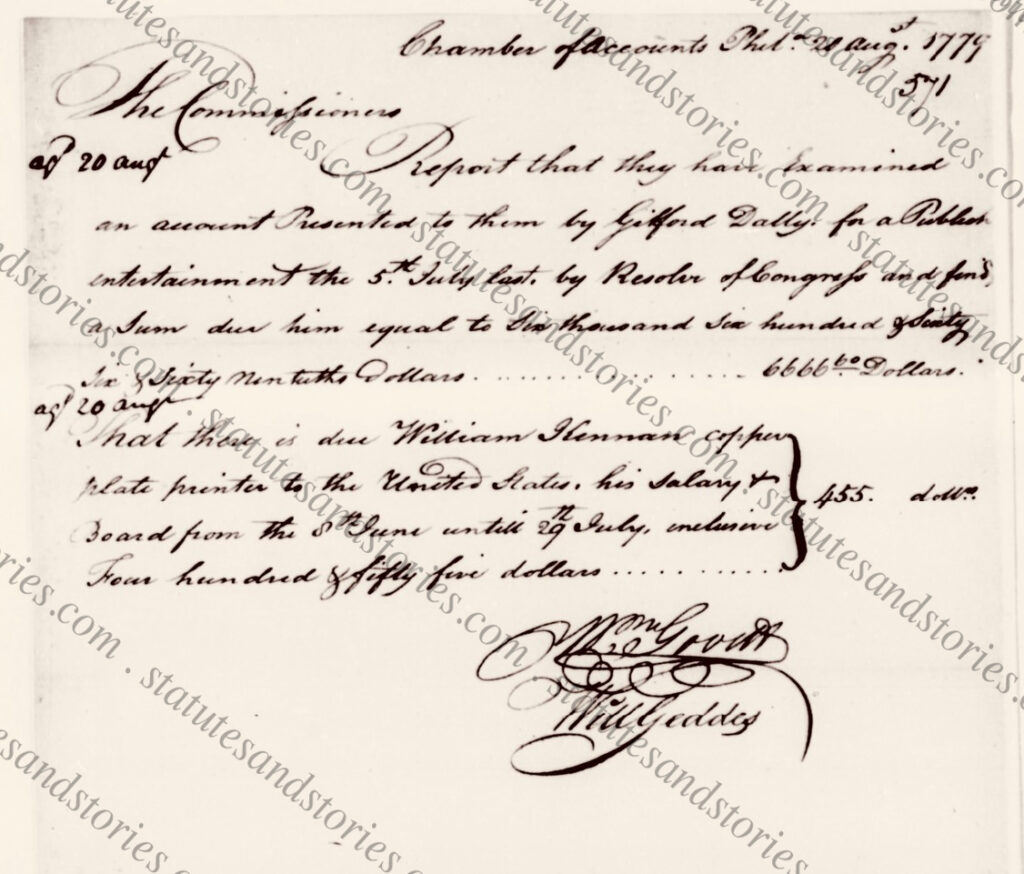

Pictured above is a Congressional report evidencing payment to Gifford Dalley for “public entertainment” on 5 July 1779.[24] Despite these elegant wartime affairs, Dalley discontinued operations at City Tavern in late 1779. During a period of inflation Dalley was likely impacted by the fixed scale of tavern prices set by the Philadelphia County’s Court of Quarter Sessions.[25]

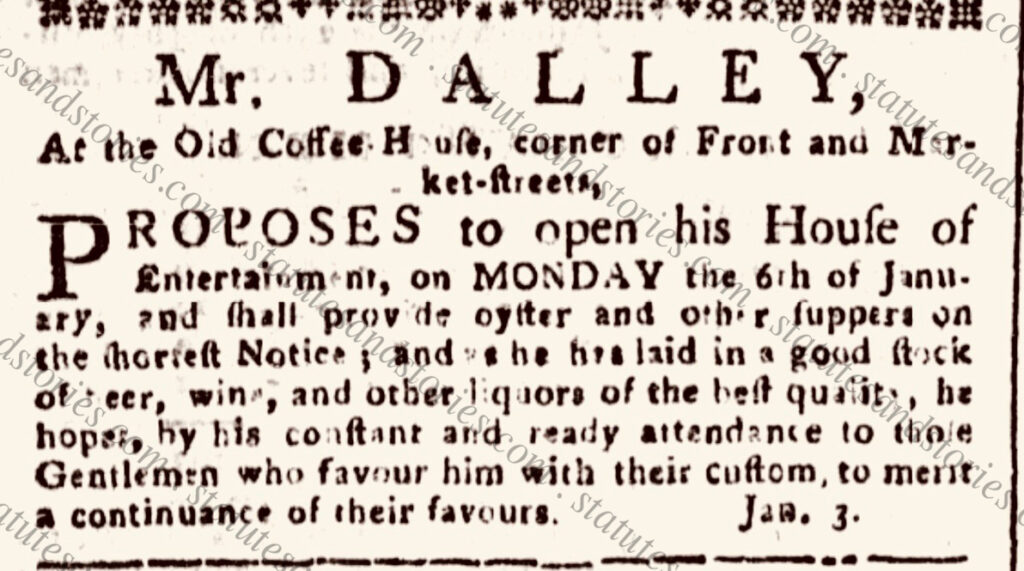

After the war, Dalley operated the Merchant’s Coffee House (also known as the London Coffee House) on the corner of Market and Front streets in Philadelphia. In an ad from January 1783 Dalley described the “good stock of beer, wine and other liquor of the best quality” that was available along with “oyster and other suppers on the shortest of notice.”[26]

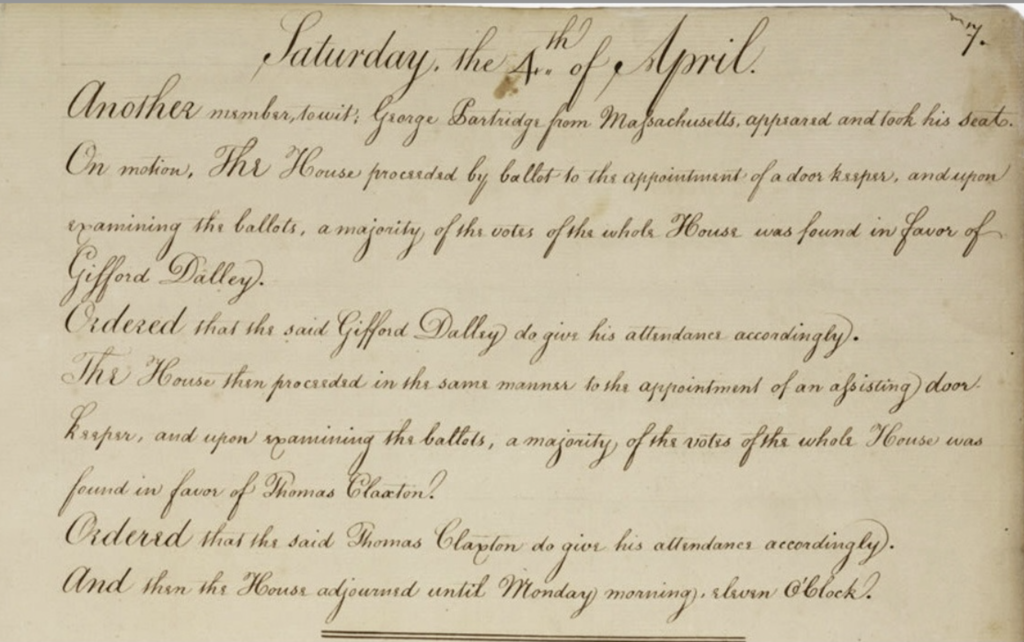

Gifford Dalley was elected doorkeeper for the House of Representatives on 4 April 1789, along with an assistant doorkeeper and sergeant at arms. [27] Dalley held the doorkeeper position during the 1st through 3rd Congress, moving from New York to Philadelphia with Congress in 1790.

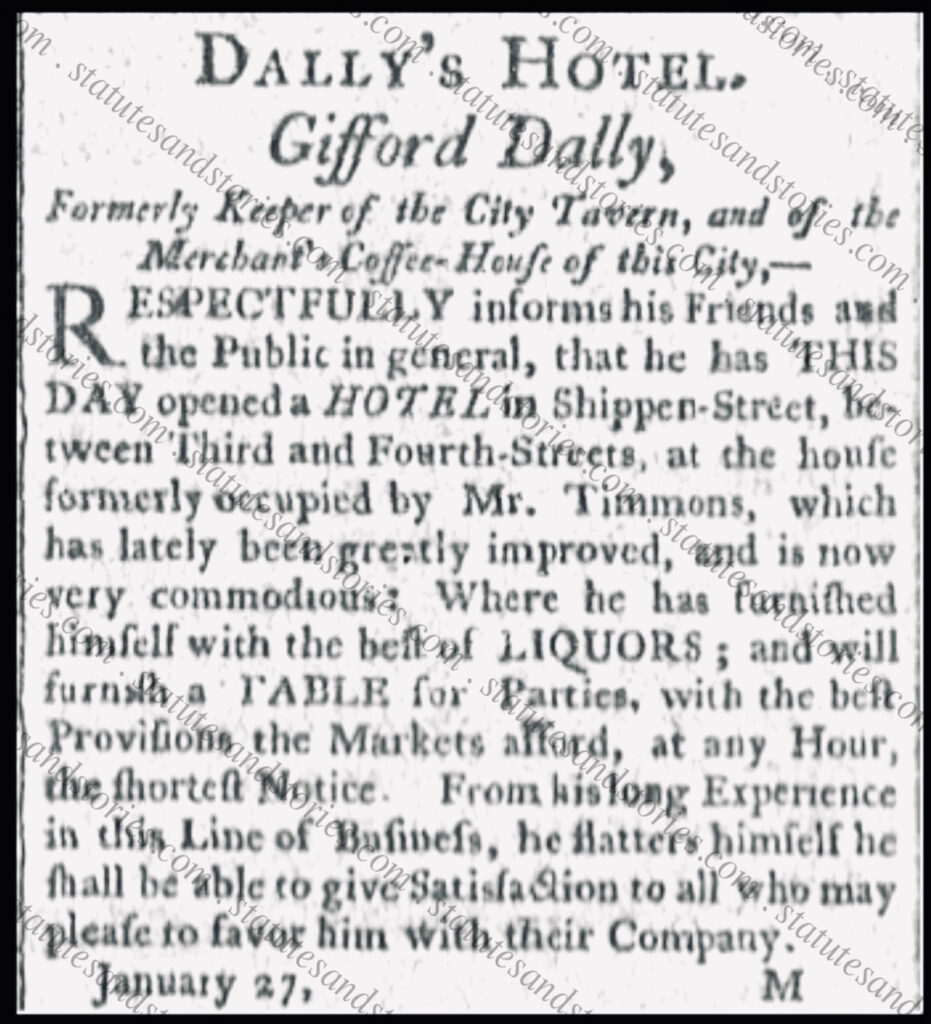

A decade later, after his tenure as the doorkeeper for Congress, Gifford opened Dally’s Hotel in Philadelphia on Shippen Street between Third and Fourth Streets. In the advertisement pictured below from 1794 he described that the newly renovated hotel was “greatly improved and is now very commodious.” In addition to offering the “best liquors” Gifford advertised that he would furnish “the best provisions the markets afford, at any hour” based on his “long experience in this line of business.” The top of the advertisement emphasized that Gifford was “formerly the keeper of City Tavern and the Merchant’s Coffee House.”[28]

The newly fashionable French concept of “hotel,” gained popularity after the American Revolution. The word hotel denoted an establishment which was fancier than an ordinary “tavern.” Two years after its well-publicized opening, Dalley’s Hotel closed its doors in 1796. Both Gifford and his daughter Kitty died of Yellow Fever in 1798.[29]

This post is part of a multi-part series discussing the extended Dalley family and the taverns/boarding houses that they operated. Part II continues with a discussion of Miss Marry Dalley’s boarding house. Part III discusses sister Catherine Dalley Simmons (Simmons’ Tavern). Sister Elizabeth Dalley Frances (Fraunces’ Tavern) will be discussed in Part IV (pending). Genealogical records of the Dalley/Simmons/Francis/Fraunces family and as yet unanswered questions for future researchers will be discussed in Part V (pending).

Endnotes

[1] Primary sources, including correspondence, newspapers, and the Congressional Journal spell Gifford and Mary’s last name as Dalley, Dally, Dailey and Daley.

[2] Gifford Dalley operated City Tavern beginning in August of 1778 after the British departed Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Packet, 6 August 1778, page 3. In 1783 he became the proprietor of the Merchant’s Coffee House in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Packet, 14 January 1783. He opened Dalley’s Hotel in January of 1794. Dunlap & Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, March 10, 1794.

[3] In the early 1780s the Massachusetts delegates to Congress boarded with Miss Dally, including Artemas Ward and Samuel Holten. Other notable boarders included Dr. John Jones who is credited as being the “Father of American Surgery” due to his widely circulated surgical handbook.

[4] Elizabeth Dalley married Samuel Fraunces at Trinity Church on 30 November 1757.

“New York, Church Records, 1660-1954,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QGPJ-9Q8S:10 October 2019), Samuel Francis and Elizabeth Dally, 30 Nov 1757; citing Marriage, New York City, New York, United States, multiple churches, New York.

[5] Catherine Dalley married John Simmons on 28 December 1758 after her first husband, William Slater, passed away two years earlier.

[6] W. Harrison Bayles, Old Taverns of New York (1915), xv-xvi.” In the years preceding the Revolutionary War, “taverns or public houses brought together a cross-class political network that would be necessary for the coherence of a revolutionary alliance.” Benjamin L. Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2007), 18-19. Taverns became “the perfect venues for revolutionaries seeking to surmount the challenges of political mobilization.” Carp at 63. Indeed, the very name of the “Sons of Liberty” may have been inspired by tavern clubs prior to the war. Carp at p. 85.

[7] In the years preceding the Revolutionary War, “taverns or public houses brought together a cross-class political network that would be necessary for the coherence of a revolutionary alliance.” Benjamin L. Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2007), 18-19. Taverns became “the perfect venues for revolutionaries seeking to surmount the challenges of political mobilization.” Carp at 63.

[8] During the 18th Century Philadelphia was the nation’s largest city. In 1787, Philadelphia’s population numbered around 40,000. New York, the nation’s second largest city, had approximately 25,000 residents. Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (2009), 73.

During most of the Revolutionary War, Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital. Congress resided in New York from 1785 until 1790. Congress returned to Philadelphia in 1790 until the Jefferson Administration moved into Washington, D.C., in the year 1800.

[9] Carp at 65.

[10] History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “DALLEY, Gifford,” https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/D/DALLEY,-Gifford/ (July 02, 2023)

[11] Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884 (1884), 1:291, note.

[12] John Adams diary, 29 August 1774, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-02-02-0004-0005.

[13] Scharf & Westcott, 1:291.

[14] Constance V. Hershey, Historic Furnishings Plan: City Tavern (Independence National Historic Park, 1974), p. iii. http://npshistory.com/publications/inde/hfp-city-tavern.pdf

[15] Gifford Dalley was retained under an agreement dated 8 July 1778 by the investor/subscribers who owned City Tavern. Hershey, p. 19.

[16] Dunlap and Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, 20 August 1778.

[17] John D.R. Platt, Historic Resource Study: The City Tavern (Independence National Historic Park, 1973), 139.

[18] William C. Ellery, “Diary, June 28-July 23, 1778”, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 11 (1887): 477-78. Ellery was a member of the Rhode Island delegation who likely participated in the usual thirteen toasts during dinner. Pennsylvania Evening Post, 8 July 1778.

[19] Pennsylvania Evening Post, 25 July 1778.

[20] Platt, 141.

[21] Platt, 140-144.

[22] Fold 3….(cite pending).

[23] Platt, 148-149.

[24] Congressional Report, 20 August 1779….(cite pending)

[25] Platt, 156; Charles R. Barker, “Colonial Taverns of Lower Merion,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, III, 227.

[26] Pennsylvania Packet, January 14 1783.

[27] https://todaysdocument.tumblr.com/post/81678502292/congressarchives-on-april-4-1789-the-house

[28] Gazette of the United States, 17 February 1794.

[29] https://philahistory.org/2014/05/05/the-black-bear-tavern-and-ball-alley/