Gouverneur Morris’ Amputation and Recovery

Newly uncovered receipts shed light on medical care in 1780

Of the fifty-five delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention, Gouverneur Morris was one of the most recognizable. Along with George Washington and Ben Franklin, Gouverneur Morris stood out in a crowd due to his height and his prosthetic left leg. Although he would briefly experiment with a more cumbersome copper leg, Morris was famous for his simple wooden peg leg and brilliant oratory. [1] A newly uncovered set of receipts sheds light on the state of medical care in 1780 and Morris’ recovery.

While tall tales would subsequently be told about Morris’ injury, his left leg was amputated following a carriage accident on May 14, 1780. At the time, Morris was twenty-eight years old. Despite his youth, Morris was one of the authors of the New York Constitution (1777) and the youngest signatory to the Articles of Confederation (1778). In 1787 Morris would be selected to prepare the final draft of the Constitution.

Carriage Accident

Although rumors circulated that Morris lost his leg as a “consequence of jumping from a window in an affair of gallantry,” [2] there is abundant evidence that his injury was the result of a mundane accident in Philadelphia which mangled his leg in the spokes of a carriage wheel. News of Morris’ unfortunate injury is repeatedly mentioned in correspondence between the founding generation which reached as far as John Jay in Spain (who was serving as the American minister to Madrid).

The first accounts of Morris’ accident appear in Philadelphia diaries on May 14, 1780. Samuel Holten, a Congressional delegate from Massachusetts, merely noted on May 14 that “Governeur Morris had his leg cut off.” In a letter dated May 16 to Congressman George Partridge, Holten elaborated that, “last Sunday morning Governr Morris got into his carriage at the city tavern to ride out and his horses took fright and he endeavoring to get out shattered one of his legs to pieces so that it was immediately taken off.” Jacob Hilzheimer recorded in his diary on May 14 that, “Gouverneur Morris Esq., a member of Congress broke his leg by jumping out of a phaeton as the horses were running away.”

Congressional delegate Wiliam Churchill Houston provides a more detailed account in a letter to Philip Schuyler written between May 13 through May 15:

I am unhappy this morning to inform you of an accident which happened yesterday to Mr. Gouveneur Morris. He was riding out in a phaeton, and the horses taking a fright ran away in the street, struck the carriage against a post, broke it all to pieces and in the shock fractured Mr. Morris’s ankle to such a degree that it became necessary to take off his leg immediately. He bore the operation with amazing firmness.

On July 6 Robert R. Livingston wrote to John Jay in Madrid that, “You have I dare say heard of poor Morris misfortune in the loss of his leg. He bears it with magnanimity & is in a fair way of recovery. I feel for him & yet am led to hope that it may turn out to his advantage & tend to fix his desultory genius to a point in which case it can not fail to go far.”

At the time of his injury Morris was a bachelor with a reputation for seeking companionship from single and married women. By contrast, John Jay was known as a devout family man. In an uncharacteristic, off-color remark, Jay joked with Livingston in letter dated September 16 that Gouverneur’s injury “has been a Tax on my Heart. I am almost tempted to wish he had lost something else.” [4]

As recently described by Professor Dennis Rasmussen, there have been “persistent rumors throughout Morris’s life that the carriage accident was merely a convenient cover story and that he had actually shattered his ankle jumping out of a bedroom window in order to avoid the wrath of an ill-timed husband.” Rasmussen concludes that while there is no corroborating evidence supporting the rumor, it “cannot be disproven.” [5]

Receipts purchased by the American Philosophical Society

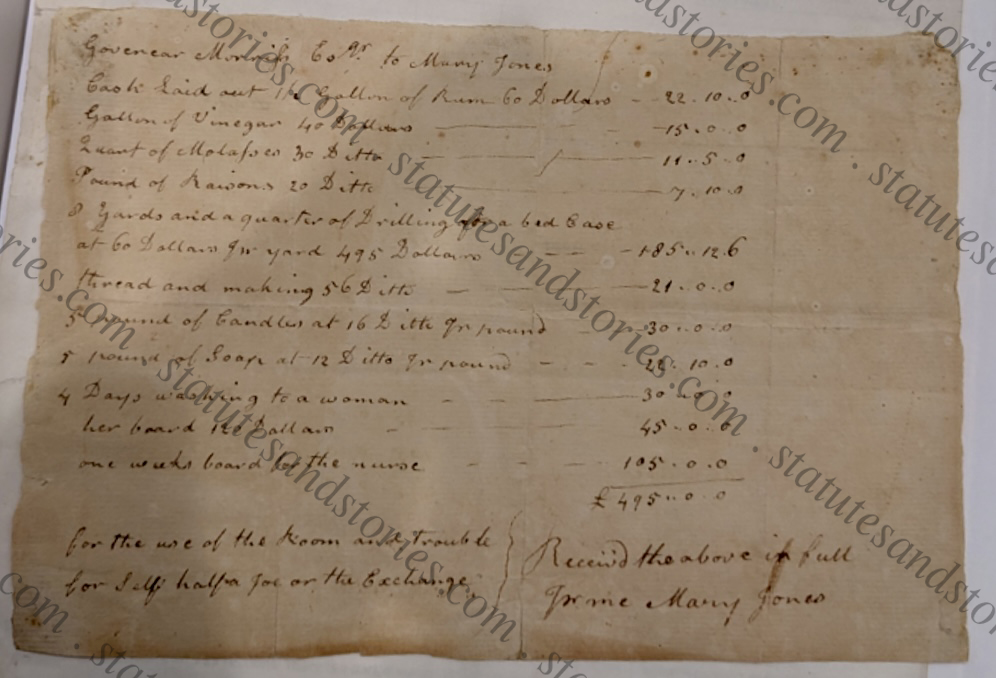

Recently uncovered receipts held by the American Philosophical Society provide insights into what can be understood as state-of-the-art medical care in 1780. At the time of his injury, Morris was a former Congressional delegate from one of America’s most influential, aristocratic families. [6]

The following information is revealed in a receipt from Mary Jones, a Philadelphia shopkeeper. [7] During his convalescence, Morris was charged for the following goods and services:

- 1/2 gallon of rum

- 1 quart of molasses

- 1 pound of raisins

- 1 gallon of vinegar (likely used as an antiseptic)

- 2 1/4 yards of fabric (drilling) for a “bed case”

- 5 pounds of candles

- 5 pounds of soap

- board and washing for a nurse

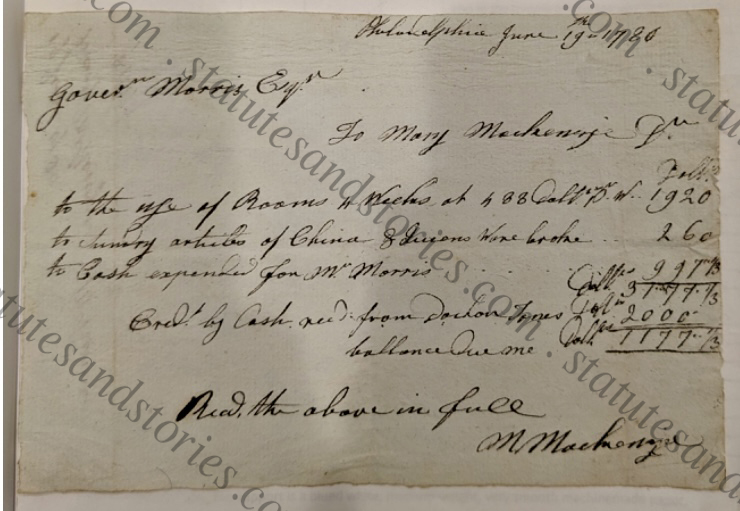

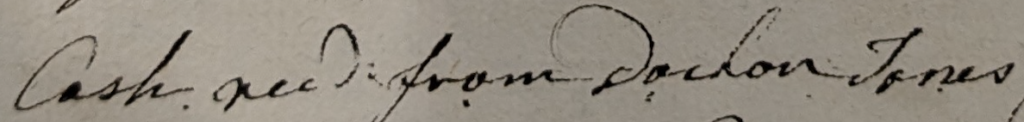

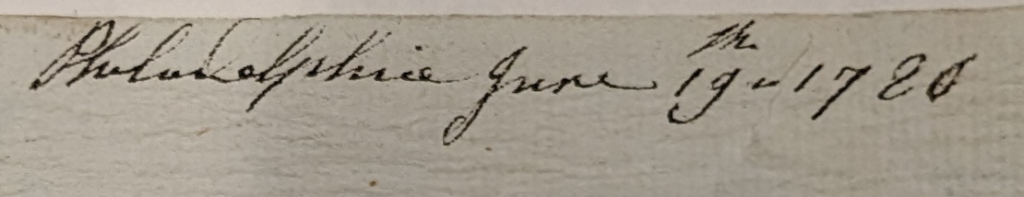

A second receipt dated 19 June 1786 from Mary Mackenzie indicates that Morris was charged for:

- the “use of rooms” for 4 weeks;

- “sundry articles”

Philadephia’s first street directories were published in 1785. Assuming that she hadn’t moved locations, Mary Mackenzie operated a boarding house on the corner of Second and Union Streets, which was only a few blocks from the location of Morris’ carriage accident.

Interestingly, MacKenzie’s receipt reflects that Morris received a credit for cash which was extended by “Doctor Jones.” This is consistent with contemporaneous reports that Gouverneur Morris was good friends with doctor John Jones, who happened to be out of town at the time of the injury. For this reason, the amputation was performed by another doctor, James Hutchinson.

According to Morris biographer Max Mintz, because doctor Jones was unavailable, several other well-known practitioners were called upon to treat Morris’ injured leg. [8] When doctor Jones subsequently arrived he was not convinced that amputation had been necessary. According to Morris’ first biographer, Jared Sparks, “Dr. Jones was never satisfied with the precipitancy of the attending physicians, in advising an amputation, believing the fracture was not such as to render that extreme process necessary…” Sparks recounts that the case was commonly cited as “proof of unskilled management and the rashness of hasty decision.” [9]

Whether or not amputation was ultimately necessary, Gouverneur Morris took his injury in stride. When a friend attempted to console Morris following his injury, Morris reportedly told him, “My good sir, you argue the matter so handsomely, and point out so clearly the advantages of being without legs, that I am almost tempted to part with the other.” [10]

As pointed out by Morris biographer James Kirchke, the surgical procedure was successful and never required revision to the stump. After his rehabilitation, Morris often walked nine miles per day. “On his wooden leg he climbed to the top of the steeple at the Cathedral of Bruges.” [11]

Use of Vinegar as an antiseptic

During the Revolutionary War, the “free use vinegar” was understood to help fight disease. For example, a letter dated 25 May 1777 from General Nathanael Greene to George Washington explained:

Upon enquiry I find the Camp feever begins to prevail among some of the Troops. Nothing will correct this evil like the free use of Vinegar—the men feed principally upon Animal food, which produces a strong inclination to putrefaction—Vegetables or any other kind of food cannot be had in such plenty as to alter the state of the habit—Vinegar is the only sovereign remidy. Cost what it may I would have it in such plenty as to allow the men a Gill if not a half Pinte a day. If cyder Vinegar cannot be had in such plenty as the State of the Army requires—Vinegar can be made with Molases Water & a little flour—to produce a fermentation one Hogshead of Molases & one Barrel of Rum will make Ten hogsheads of Vinegar.

Vinegar can be made from the simple state of the materials fit for use in a fortnights time—I think it my dear General an object of great importance to preserve the health of the Troops. What can a sickly army do, they are a burden to themselves & the State that employs them—All the accumulated expence of raising & supporting an Army is totally lost—unless you can find means to preserve the health of the Troops—No General however active himself or what ever may be his knowledge or experience in the Art of War, can execute any thing important while the Hospitals are crowded with the Sick—Besides such a spectacle as we beheld last Campaign is shocking to the feelings of humanity, distressing to the whole Army to accomodate the Sick—but above all the Country is robd of many useful Inhabitants and the Army of many brave Soldiers.

Thus, based on the two receipts discussed above we can conclude that Gouverneur Morris’ wound was sanitized with the healthy application of vinegar. Moreover, Morris used whiskey spiked with molasses and raisins for other medicinal purposes. It also helped that his nurse had access to five pounds of soap and new, clean bedding. If other rumors are true, Morris received additional care from Elizabeth Plater (the future First Lady of Maryland), but this is a story for another day.

Footnotes

[1] Morris’ thirty-nine-inch oak peg leg is on display at the New-York Historical Society. Referred to as “the tall boy” by his enemies, Morris was over six feet tall. According to Richard Brookhiser, Morris was “a man of imposing physical stature.” Morris subsequently experimented with copper and cork legs when he was in Europe, but refused to allow his injury to slow him down “physically or socially.” Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris, The Rake Who Wrote the Constitution (2008), 42, 63.

[2] Diary of Henry Temple, Viscount Palmerston (the father of British Prime Minister Henry John Temple), cited by Brookhiser at p. 61.

[3] Extracts from the Diary of Jackob Hiltzheimer of Philadelphia, 1768-1798, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Apr., 1892, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Apr., 1892), pp. 93-102.

[4] John Jay to Robert R. Livingston, 6 July 1780.

[5] Dennis Rasmussen, The Constitution’s Penman: Gouverneur Morris and the Creation of America’s Basic Charter (2023), 17.

[6] Morris’ half-brother, Lewis Morris, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Another half-brother, Richard Morris, was the Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court. Illustrating the divided loyalties within his family, another half-brother, Staats Long Morris, was a British general and member of Parliament.

[7] The front of the receipt is undated. The back is signed by Mary Jones with the year 1780 and a monetary value which matches the front, 495 pounds.

[8] As America’s largest city at the time, Philadelphia was known for its outstanding surgeons. While some may question Dr. Hutchinson’s young age when he performed Morris’ amputation, Hutchinson served as the surgeon-general of Pennsylvania and likely performed his fair share of amputations during the Revolutionary War. Nevertheless, he would later turn down an appointment as a professor of surgery at the University of Pennsylvania. James J. Kirschke, Gouverneur Morris: Author, Statesman, and Man of the World (2004), 117-118.

[9] Jared Sparks, The Life of Gouverneur Morris (1832), vol. 1, 223.

[10] William Howard Adams, Gouverneur Morris: An Independent Life (2003), 126.

[11] Kirschke, 117.