Background about the founding of South Carolina: Following the English Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s death, the British monarchy was restored under King Charles II. After his restoration, King Charles was indebted and lacked cash. In 1663 he granted a Charter to the Carolina Territory to eight former generals.

In 1669, the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina was co-written by attorney/philosopher John Locke and Anthony Cooper. The document was modeled after Locke’s “A Letter Concerning Toleration.” The Fundamental Constitutions was signed by all eight “Lord Proprietors” who had been granted the Carolina charter, which included the majority of the land between Virginia and Florida. Locke would later become famous as a liberal political philosopher for his role developing the theory of a social contract and rule by “the consent of the governed.” Click here for a link to Locke’s Two Treatises on Government.

After the Fundamental Constitutions were prepared settlers brought the governing document to Charles Town, which was founded in 1670 on the inlet peninsula formed by the junction of the Ashley and Cooper rivers and the Atlantic Ocean. Charles Town was later renamed as Charlestown after the American Revolution in 1783.

During the colonial period, Charlestown became the busiest seaport south of Philadelphia. While New York, Boston and Philadelphia were larger, Charlestown became the wealthiest city in the colonies. Huge profits were amassed by importing slaves and exporting indigo, rice, sugar, tobacco and later cotton. It is believe that up to 40% of the slaves imported into American came through Charlestown harbor as part of the “Middle Passage” leg of the “Triangle Trade.” The notorious Gadsden Wharf, the site where more African Americans arrived and were sold than any other location, will be the future home in 2020 of the International African American Museum.

Voltaire praised the religious tolerance permitted by Locke’s Fundamental Constitutions when he exclaimed, “Cast your eyes over the other hemisphere, behold Carolina, of which the wise Locke was the legislator.” Nevertheless, the Fundamental Constitutions were far from being democratic since they enshrined a powerful aristocracy, serfdom and slavery in the colony.

In particular, Article 110 of the Constitutions provided that “Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves, of what opinion or religion soever.” Under this provision owners held the absolute power of life and death over their slaves. It is hard to reconcile Article 110 with Article 107 which attempted to grant freedom of worship to all as follows:

Since charity obliges us to wish well to the souls of all men, and religion ought to alter nothing in any man’s civil estate or right, it shall be lawful for slaves, as well as others, to enter themselves, and be of what church or profession any of them shall think best, and, therefore, be as fully members as any freeman. But yet no slave shall hereby be exempted from that civil dominion his master hath over him, but be in all things in the same state and condition he was In before.

South Carolina’s Slave Code and Act of 1740: The 1690 “Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves” codified the institution of chattel slavery in South Carolina. Among other things, slaves were required to get written passes to travel. Those who lacked permission to travel were considered runaways. Barbaric punishments under the 1690 Act included whipping, branding, nose-slitting. Runaways were subject to being branded with an R on the cheek and/or loss of an ear. Other penalties for a range of offenses included castration and the severing of a tendon.

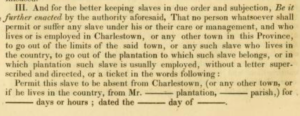

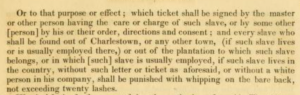

Section III of the 1690 Act contained the travel requirements is copied below:

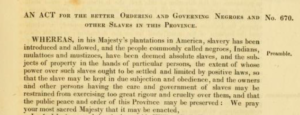

In 1739 the Stono slave rebellion resulted in the imposition of an even stricter slave code, the “Bill for the better ordering and governing of Negroes and other Slaves in this Province,” known as the “Negro Act” of 1740 (hereinafter the “Act of 1740”). The Act of 1740 codified the denial of rights for slaves under English common law and deemed them legal nonentities. Slaves could not testify under oath, writing was prohibited, and drumming and playing horns was outlawed. The 1740 Act even regulated clothing for slaves. The Act became the basis for the institution of slavery in South Carolina until 1865 and influenced slave codes throughout the South.

The statutes pictured above are taken from Thomas Cooper’s 1838 codification of the Statutes at Large of South Carolina. In the late 1830’s the Legislature of South Carolina authorized the publication of all South Carolina statutes along with a comprehensive digest. Click here for a link a separate post about Thomas Cooper, his publications and prosecution under the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Copied below are links to Coopers’s nine volume Statutes at Large of South Carolina (the last few volumes were completed by David McCord):

Volume 1 (Acts of a Constitutional Character)

Volume 4 (1752-1786)

Volume 7 (Acts relating to Charleston, Slaves, Courts and Rivers)

Volume 8 (Acts relating to Corporations and the Militia)

Volume 9 (Acts relating to Roads, Bridges and Ferries)

Additional reading:

History of South Carolina (Snoweden, ed. 1920)

Impact of the Steno Rebellion (Thoughco.com)

South Carolina Encyclopedia, Slaves Codes

Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America (Douglas Egerton, 2009)

Water from the Rock, Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age (Sylvia Frey 1991)