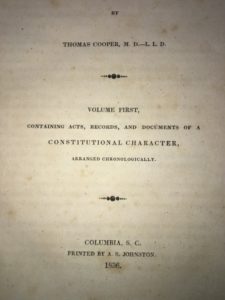

Thomas Cooper and the Statutes at Large of South Carolina: In the 1830’s the Legislature of South Carolina authorized the publication of all South Carolina statutes along with a comprehensive digest. The “fit and capable person” selected for the job was Thomas Cooper, the President of South Carolina College (today the University of South Carolina).

Cooper was one of the leading public intellectuals of his generation, among a very crowded field. John Adams described Cooper as “a learned, ingenious, scientific and talented madcap.” Click here for a link to Adams’ letter of July 22, 1813 to Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was a good friend and admirer of Cooper, who served as the first professor of natural science at the University of Virginia. Click here for a link to Jefferson’s letter of 9/1/1817 to Cooper describing Jefferson’s plans for the University of Virginia. Cooper was also personal friends with President James Madison and was recognized by Madison for his work on “Congreve” rockets which were used by the British during the War of 1812. Click here and here for letters from Cooper to Madison summarizing his analysis.

According to Jefferson “Cooper is acknowledged by every enlightened man who knows him, to be the greatest man in America, in the powers of mind, and in acquired information; and that, without a single exception.” Click here for a link to Jefferson’s letter of March 1, 1819 to Joseph Carrington.

His other works include Political Essays (1800); An English Version of the Institutes of Justinian (1812); Lectures on the Elements of Political Economy (1826); A Treatise on the Law of Libel and the Liberty of the Press (1830); a translation of Broussais’ On Irritation and Insanity (1831), various essays including, “The Scripture Doctrine of Materialism,” “View of the Metaphysical and Physiological Arguments in favour of Materialism,” and “Outline of the Doctrine of the Association of Ideas.

Cooper’s biographer, Dumas Malone, argues that “Perhaps no man of Cooper’s generation did more than he to advance the cause of science and learning in America.” Click here for a link to Dumas Malone’s THE PUBLIC LIFE OF THOMAS COOPER 1783–1839 (AMS Press 1979)

Additional reading:

Thomas Cooper, Early American Public Intellectual, Eugene Volokh

History of Science in America, Marc Rothenberg

Alien and Sedition Acts (Library of Congress)

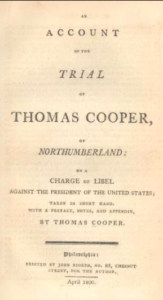

The Libel Trial of Thomas Cooper

An Early History of the University of Virginia (Nathaniel Cabell, 1856)

A Treatise on the Law of Libel and the Liberty of the Press (Thomas Cooper, 1830)

Copied below are links to Coopers’s nine volume Statutes at Large of South Carolina (the last few volumes were completed by David McCord):

Volume 1 (Acts of a Constitutional Character)

Volume 4 (1752-1786)

Volume 7 (Acts relating to Charleston, Slaves, Courts and Rivers)

Volume 8 (Acts relating to Corporations and the Militia)