Crimes Act of 1790: the first federal crimes codified by the first Congress

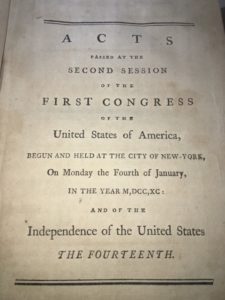

[First Congress, 2nd Session; Ch. 9, 1 Stat. 112]

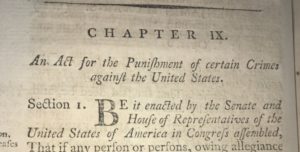

“An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes Against the United States,” adopted on April 30, 1790.

The Crimes Act of 1790 (otherwise known as the “Federal Criminal Code of 1790”) was the first effort by the first Congress to establish criminal offenses punishable by the new federal government. The Act created twenty-three federal crimes and set forth their respective punishments. The Act also addressed criminal procedures for the federal courts and amended the recently adopted Judiciary Act of 1789.

The newly adopted Constitution explicitly enumerated Congressional authority to define and punish the crimes of piracy, counterfeiting, felonies on the high seas, and “offenses against the Law of Nations.” Other crimes were not specifically mentioned in the Constitution, but could be implied from other delegated Congressional powers. Constitutional scholars have observed that the first acts passed by the first Congress provide a particularly good window into the intent of the founders, since there was substantial overlap between the drafters of the Constitution and the members of the first Congress.

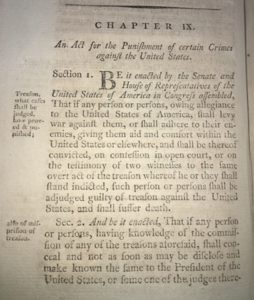

Special definition and treatment for treason: The Constitution singled out the crime of treason for special treatment in Article III, Section 3. The framers defined treason narrowly, with the following protections for accused defendants: “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.”

James Madison explained the reasons why the crime of treason deserved particular care in Federalist 43:

But as new-fangled and artificial treasons have been the great engines by which violent factions, the natural offspring of free government, have usually wreaked their alternate malignity on each other, the convention have, with great judgment, opposed a barrier to this peculiar danger, by inserting a constitutional definition of the crime, fixing the proof necessary for conviction of it, and restraining the Congress, even in punishing it, from extending the consequences of guilt beyond the person of its author.

Madison’s warning proved to be all too accurate and presaged the violent Reign of Terror that began in the 1790’s following the French Revolution.

List of crimes: Other crimes were not specifically mentioned in the Constitution, but could be inferred from other Congressional powers. The categories of crimes listed in the Act included: 1) treason; 2) misprision of treason (deliberate concealment); 3) willful murder occurring on federal property; 4) rescue/attempted rescue of a body following an execution; 5) misprision of felony; 6) “man-flaughter”; 7) piracy; 8) “acceffory before the fact”; 9) “acceffory after the fact”; 10) confederate to piracy; 11) maiming; 12) forgery/counterfeiting/falsifying federal securities or coin; 13) altering/corruption of federal records; 14) larceny; 15) receiving stolen goods; 16) perjury; 17) subornation of perjury (contracting with another to commit perjury); 18) bribery; 19) obstruction a federal officer; 20) rescue of an inmate; and 21) violation of safe conduct/passport.

In addition to defining federal crimes and setting forth the applicable penalty, the Act also specified the statutes of limitation for different offenses (ranging from no statute of limitation for willful murder; three years for treason and capital offenses; and two years for all other non-capital crimes). These limitations did not apply to fugitives from justice.

In cases of treason or capital crimes, defendants were granted the right to receive a copy of the indictment, a list of the jury, appointed counsel, and compulsory process. Defendants accused of treason were also entitled to a list of the prosecution witnesses. These protections were consistent with the Sixth Amendment which had not yet been ratified.

Punishments: Seven of the crimes contained in the Crimes Act were capital offenses punishable by the death penalty: treason, wilfull murder, aiding in the escape of a death row felon, counterfeiting, piracy, and murder or robbery on the high seas. The Act specified that the sole method of execution was by hanging.

Nevertheless, the relatively short list of capital crimes reflected a progressive departure from the conventions of the day when most serious offenses were punishable by death. Depending on the crime, the non-capital offenses were punishable by imprisonment for up to one year, three years, or seven years terms.

For other crimes, the Act granted federal judges discretion to assess fines or corporal punishment. For example, perjury was punishable by up to three years of imprisonment, a $800 fine, and one hour of standing in the “pillory.” A perjury conviction would also disqualify a defendant from giving testimony in court.

While corporal punishment is viewed as inhumane today, it was regularly practiced during the 18th Century. Thus the Act permitted public whipping not to exceed thirty-nine “stripes” for certain offenses, including larceny. Perhaps the most controversial provision of the Act was the ability of a judge to order the dissection of the corpse of an executed murderer. This punishment served two purposes. First, dissection was a feared deterrent which held more sway for many than the death penalty itself. Second, dissection provided cadavers for use by the medical profession. The practice was imported from Britain and dated back to the Murder Act of 1751 (25 Geo 2 c 37).

Additional English concepts that were addressed in Act included the elimination of the “benefit of the clergy” and the prohibition on the practice of “corruption of blood” as a punishment for treason. Article III, Section 3, of the Constitution outlawed the penalty of corruption by blood as a punishment for treason, whereby the descendants of a criminal were precluded from inheritance through the parent. The Act extended this constitutional prohibition to all crimes.

The tradition of benefit of the clergy, originated in the 12th Century and allowed members of the clergy to be tried by ecclesiastical courts. Over the years, the practice evolved into a literacy test where the accused was merely required to prove that they could read a verse from the bible (usually the 51st Psalm). As a practical matter, the benefit of the clergy served as a mechanism for first-time offenders to receive reduced sentences through the use of a legal fiction. The Constitution was silent on the practice, which was outlawed by the Crimes Act of 1790, presumably because it ran afoul of the separation of church and state. Although benefit of clergy was not allowed in federal court, the practice continued under state law for many years.

Background: The Act’s principal author was Connecticut Federalist Senator Oliver Ellsworth, who was a close ally of Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Ellsworth was the Chair of the Senate Committee which was also responsible for the Judiciary Act of 1789 and the Process Act of 1789. Ellsworth would subsequently be appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by President Washington. In drafting the Crimes Act, Ellsworth’s committee borrowed from the criminal laws of several states (Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and Virginia). Ellsworth was particularly well suited for this role since he had served as a practicing lawyer, state attorney and judge in Connecticut, as well as serving as a member of the Continental Congress and a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

Copy of the original Act (National Archives)

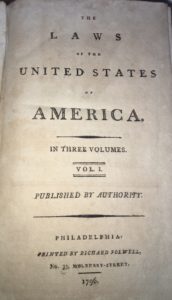

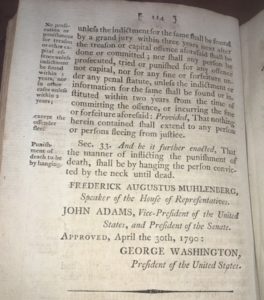

John Adams’ copy of the Laws of the United States

Further reading:

Federal jurisdiction and timeline (Federal Judicial Center)

Penalties and mandatory minimum sentencing (US Sentencing Commission)