Elizabeth Hamilton’s Pension

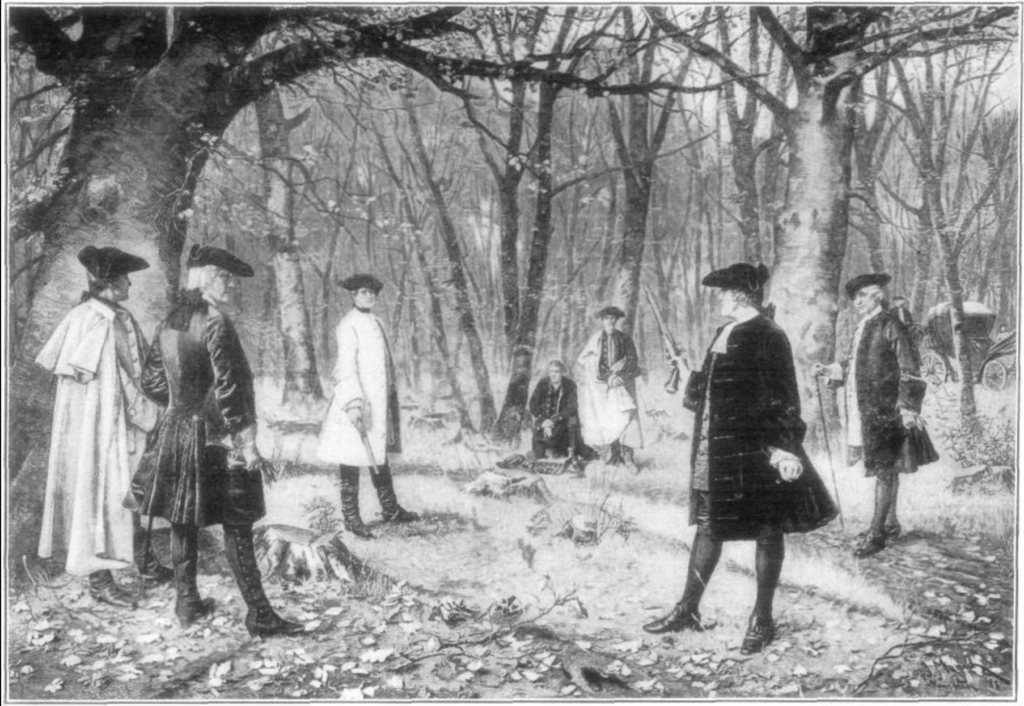

Alexander Hamilton tragically passed away on July 12, 1804, the day after his duel with Aaron Burr. Hamilton’s wife, Elizabeth Hamilton (“Eliza”), would live another fifty years, enabling her to continue the family’s tradition of public service and philanthropy. Eliza outlived all of the founding generation, passing at the age of 97 in 1854.

This post explores Eliza’s struggle to defiantly press the federal government to honor its pension and other obligations due to Alexander Hamilton, following his extraordinary life of military and public service. It is also important to acknowledge the assistance of Hamilton’s loyal friends, including Gouverneur Morris, who helped support Eliza and the Hamilton children in the lean years following Hamilton’s death.

Hamilton’s death and finances

Hamilton died at the age of 49, surrounded by Eliza and their seven children, including “Little Philip” who was only two years old. The “flood of tears” in Hamilton’s final hours led Gouverneur Morris to write that “[t]he scene is too powerful for me…I am obliged to walk in the garden to take a breath.”

In the days leading up to the duel, Hamilton wrote two letters to Eliza, who was unaware of the pending confrontation in Weehawken. In a July 4 letter, Hamilton explained to “my very dear Eliza” the “pangs” he felt “for the idea of quitting you to the anguish which I know you would feel.” Hamilton attempted to provide comfort with the idea that “I shall cherish the sweet hope of meeting you in a better world.” Hamilton signed the letter:

Adieu best of wives and best of Women. Embrace all my darling Children for me. Ever yours.

A.H.

In his final letter to Eliza, written the night before the duel, Hamilton attempted to explain the reasons for “the interview” with Burr. Hamilton closed the July 10 letter to Eliza with a familiar expression of love: “Once more Adieu, my darling, darling wife.”

In his last will and testament, Hamilton anticipated that Eliza would benefit from “patrimonial resources” from her father, General Philip Schuyler. While Eliza could expect an inheritance from her once wealthy father, Eliza did not know that Philip would pass only three months after Alexander.

Like his son-in-law, General Schuyler was land rich but cash poor, with mounting debt from struggling business ventures. With limited income to support the eight surviving Schuyler siblings, Eliza’s inheritance would only amount to annual income of $750 from farmland located near Albany and Saratoga, New York.

In Hamilton’s will he “entreated” his “Dear Children” to support “their dear Mother with the most respectful and tender attention…” Hamilton praised Eliza as “the most devoted and best of mothers,” but acknowledged that:

Though conscious that I have too far sacrificed the interests of my family to public avocations & on this account have the less claim to burthen my Children, yet I trust in their magnanimity to appreciate as they ought this my request.

In a statement of his pecuniary affairs, Hamilton estimated his net worth at $10,000, but recognized that a forced sale might not generate sufficient money to pay his debts. Sadly, Hamilton understood the risk that he was overestimating the value of his illiquid estate, leaving his family in both emotional and financial distress.

Hamilton’s statement of pecuniary affairs explained the sacrifice that he had made, but as discussed below left the door open for Eliza to pursue a pension for the Hamilton family:

In the event, which would bring this paper to the public eye, one thing at least would be put beyond a doubt. This is, that my public labours have amounted to an absolute sacrifice of the interests of my family—and that in all pecuniary concerns the delicacy, no less than the probity of my conduct in public stations, has been such as to defy even the shadow of a question.

Indeed, I have not enjoyed the ordinary advantages incident to my military services. Being a member of Congress, while the question of the commutation of the half pay of the army in a sum in gross was in debate, delicacy and a desire to be useful to the army, by removing the idea of my having an interest in the question, induced me to write to the Secretary of War and relinquish my claim to half pay; which, or the equivalent, I have accordingly never received. Neither have I ever applied for the lands allowed by the United States to Officers of my rank. Nor did I ever obtain from this state the allowan⟨ce⟩ of lands made to officers of similar rank. It is true that having served through the latter period of the War on the general staff of the U States and not in the line of this State. I could not claim that allowance as a matter of course. But having before the War resided in this State and having entered the military career at the head of a company of Artillery raised for the particular defense of this State, I had better pretensions to the allowance than others to whom it was actually made—Yet has it not been extended to me.

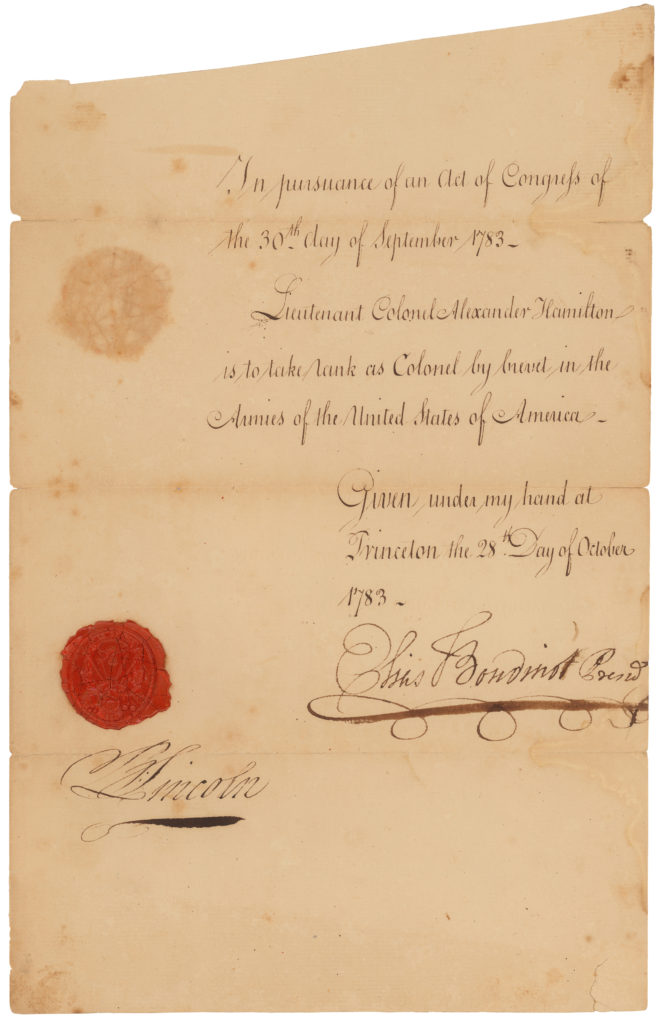

Click here for a link to high quality images at the National Archives of all four pages of Hamilton’s pecuniary statement, along with his military commission appointing him “Colonel by brevet” in 1783. Eliza would use this statement along with other evidence to finally secure a pension more than a decade later in 1816.

Future posts will explore Hamilton’s other correspondence in his final days, including a letter written to Theodore Sedgwick, a Massachusetts Congressman and fellow Federalist. Click here for Hamilton’s July 10, 1804 letter to Sedgwick warning against the danger of “dismemberment” of the country.

Gouverneur Morris summarized Hamilton’s finances in a letter to Rufus King, another of Hamilton’s close friends:

Our friend Hamilton has been suddenly cut off in the midst of embarrassments which would have required years of professional industry to set straight – a debt of between 50,000 and 60,000 dollars hanging over him, a property which in time may sell for 70,000 or 80,000, but which, if brought to the hammer, would not, in all probabilty, fethch 40,000.”

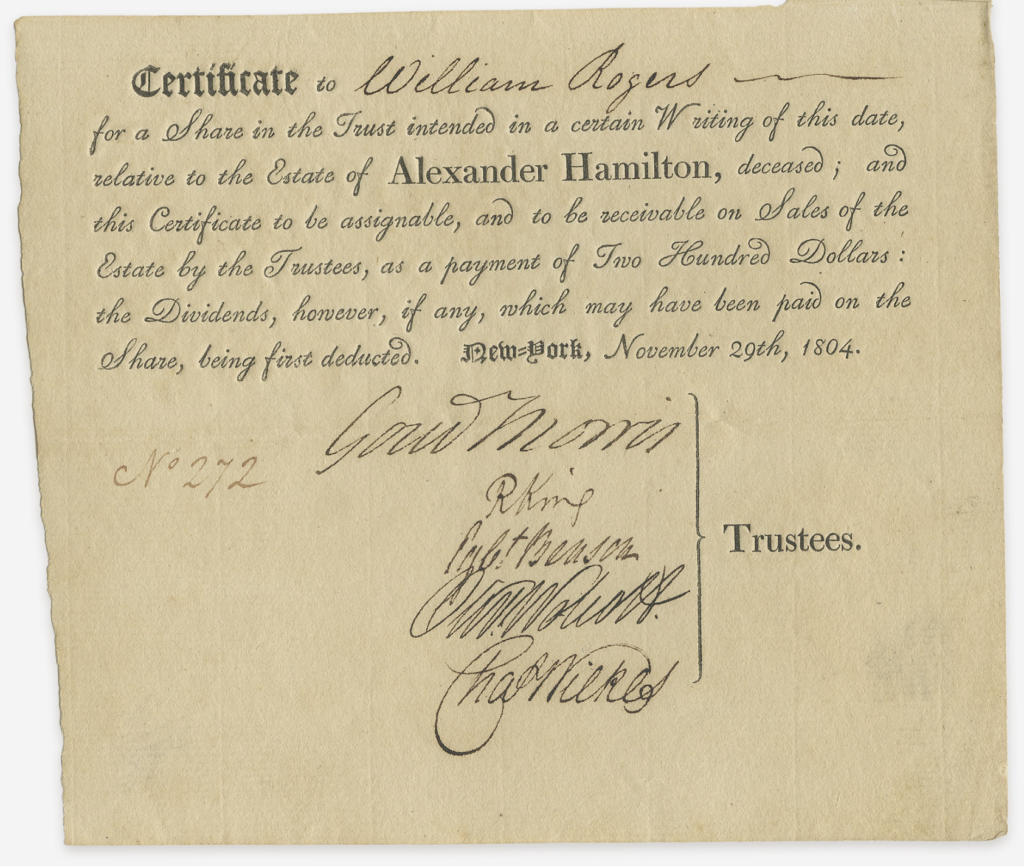

Morris, who gave the eulogy at Hamilton’s funeral, secretly raised approximately $80,000 from over 100 of Hamilton’s friends by selling shares in a trust to benefit the Hamilton family. Other New England friends donated land in Pennsylvania, all of which was concealed from the Hamilton children. Copied below is a certificate of shares sold by Gouverneur Morris, Rufus King (a Federalist Senator), Egbert Benson (former Attorney General of New York), Oliver Wolcott (the Secretary of Treasury after Hamilton), and Charles Wilkes as part of the secret charitable offering.

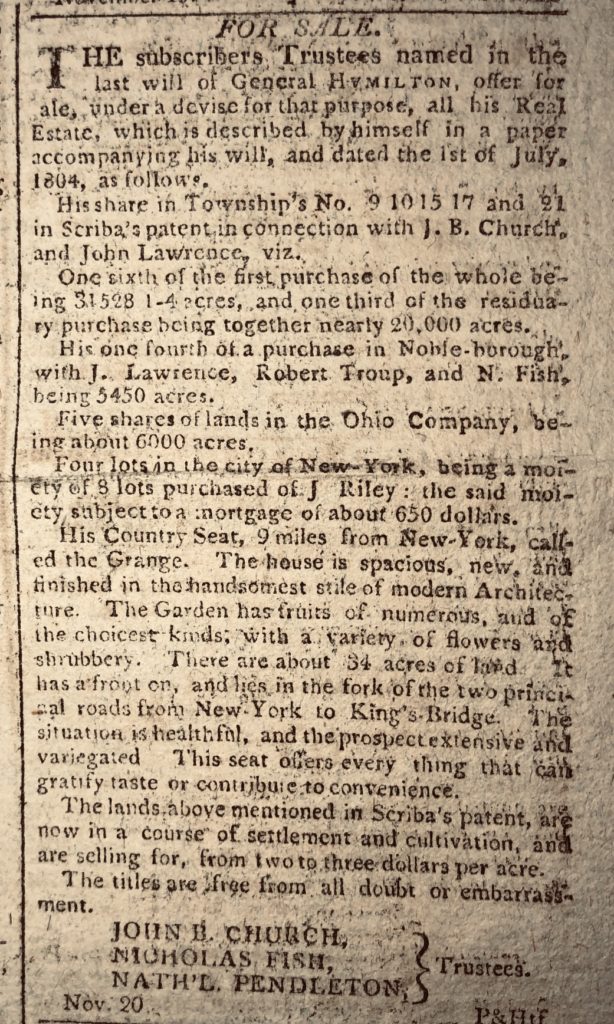

Hamilton’s executors, John Church (Angelica’s husband), Nicholas Fish, and Nathaniel Pendleton put the Hamilton Grange for sale at auction to pay off creditors. They purchased the Grange for $30,000, but sold it back to Eliza for $15,000, enabling her to remain in the cherished family homestead. Copied below is an image of the Grange which is located on 141th Street in northern Manhattan. Also pictured is a notice of estate sale in Hamilton’s newspaper the New York Evening Post in December of 1804.

Alexander Hamilton’s Support for Veterans and Pension Rights

During his life, Alexander was a champion of military pensions for his comrades-in-arms and friends who had faithfully served in the Continental Army. After the Battle of Yorktown, Hamilton represented New York in the Continental Congress where he chaired the committee that attempted to grant officers a lump sum pension equivalent to 5 years of pay. Famously, his successful financial program enabled the new Federal government to honor its financial obligations to veterans and eventually enabled President Jefferson to afford the Louisiana Purchase.

Yet, in a commendable effort to insulate himself from accusations of self dealing, Hamilton renounced “all claim to the compensations attached to my military station during the war or after it.” Click here for a link to Hamilton’s letter to Washington dated March 1, 1782 surrendering Hamilton’s pension and other rights.

Among his accomplishments, Hamilton prepared the March 21, 1783 Committee report to establish a lump sum half pay pension for army officers. The proposal was timed to address the growing tension within the army during the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy. Addressing the officers in a tense speech in Newburgh, Washington promised to lobby Congress on behalf of the solders. Hamilton in turn chaired the committee in the Continental Congress that granted officers the requested pension equivalent to 5 years pay.

Less than two months later, Hamilton’s committee sought life-long disability pensions for injured soldiers, with Hamilton similarly writing the Committee Report. Hamilton also lobbied for and wrote the Committee Report to provide compensation for Baron Von Steuben, another loyal aid and indispensable assistant to General Washington at Valley Forge.

Eliza’s Struggle for a Pension

Five years after Alexander’s death, on May 30, 1809, Eliza formally petitioned Congress for a pension based on his military service during the Revolutionary War. While it is unclear why she waited until 1809, one can speculate that she was waiting for President Jefferson’s successor, James Madison, to take office.

While her petition was initially rejected in 1810, Eliza eventually prevailed upon Congress in 1816, prior to President Monroe’s election to replace Madison. In subsequent years, Eliza secured payment of land bounties due to Revolutionary War veterans. Before her death, she also succeeded in convincing Congress to purchase Hamilton’s papers for the Library of Congress.

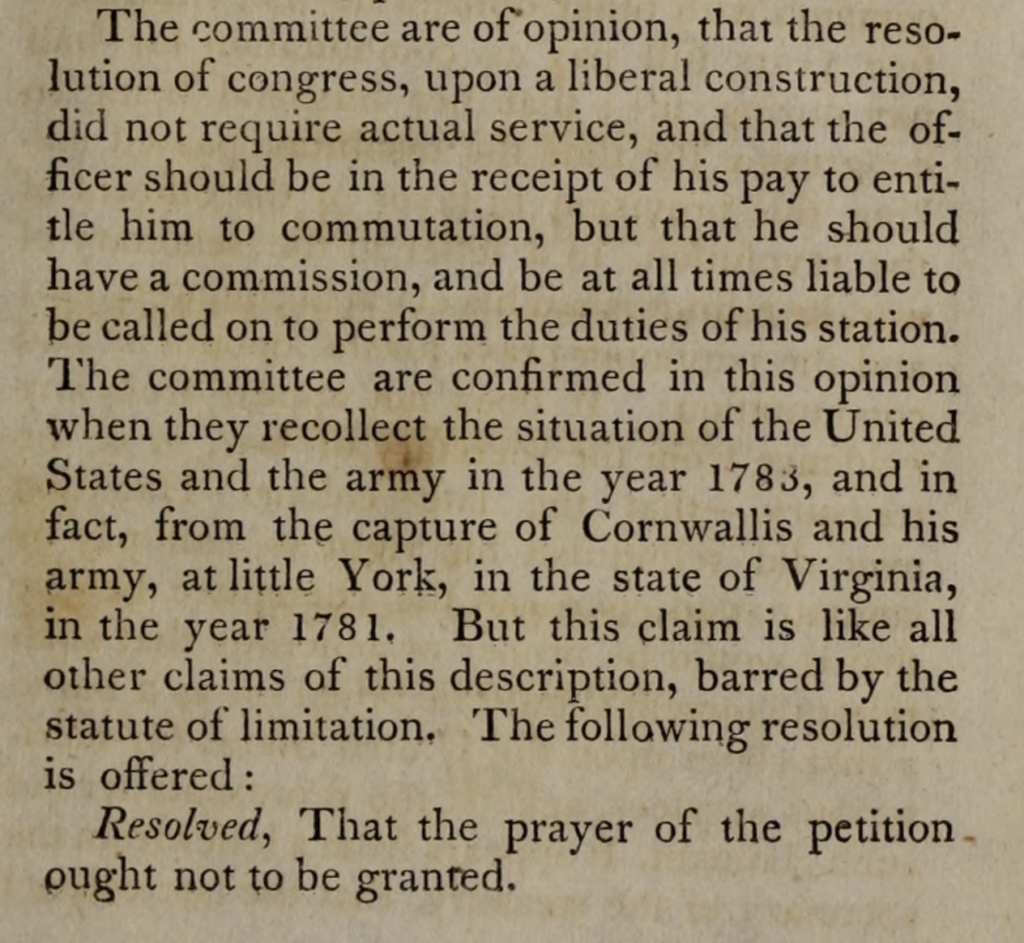

Copied below is the 1810 Report of the Committee of Claims which recognized Eliza Hamilton’s “just claim…for meritorious services” by Alexander Hamilton. The Committee expressed its opinion that “upon a liberal construction” Hamilton was entitled to receipt of his pay. Nevertheless, the committee felt itself “barred by the statute of limitation” based on the amount of time that had lapsed.

Along with her petition, Eliza submitted Alexander’s 1783 Commission as brevit Colonel in the Continental Army, pictured below, and his personal statement of his property and debts.

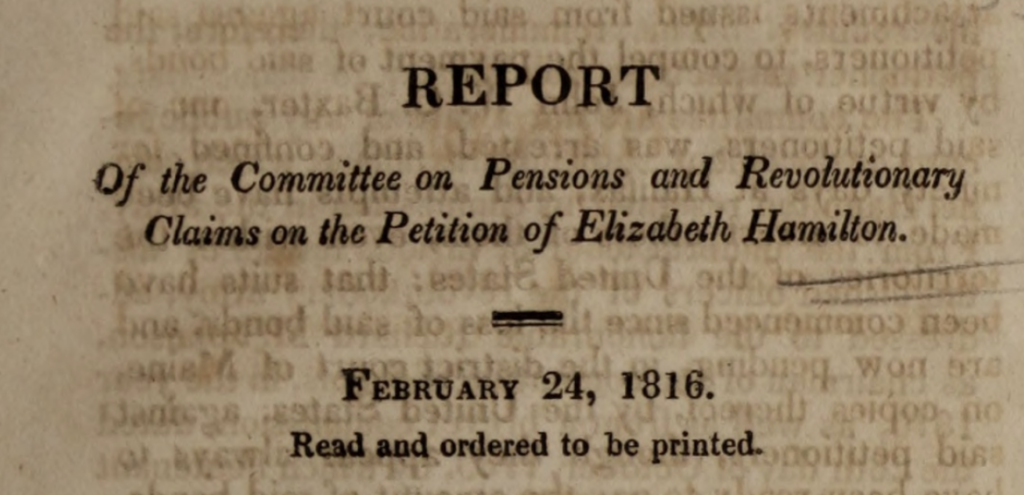

Not one to take rejection easily, Eliza successfully reapplied to Congress in 1816. This time, the Committee on Pensions and Revolutionary Claims wrote a more detailed report crediting “the uniform tenor of the various letter of distinguished officers” addressed to the Committee Chairman, Richard M. Johnson. No doubt, Eliza helped secure this correspondence from Hamilton’s friends in support of her petition.

While acknowledging that the statute of limitation continued to bar the Hamilton claim, the 1816 report was more sympathetic than the earlier 1810 report. The Committee concluded that:

services have been rendered to the country, by which its happiness and prosperity have been promoted, they are of the opinion, that to reject the claim under the peculiar circumstances by which it is characterized, would not comport with that honourable sense of justice and magnanimous policy, which ought ever to distinguish the legislative proceedings of a virtuous and enlightened nation.

Copied below is the title of the February 24, 1816 committee report, which can be viewed in its entirety by clicking on following link to the full 1816 Committee Report.

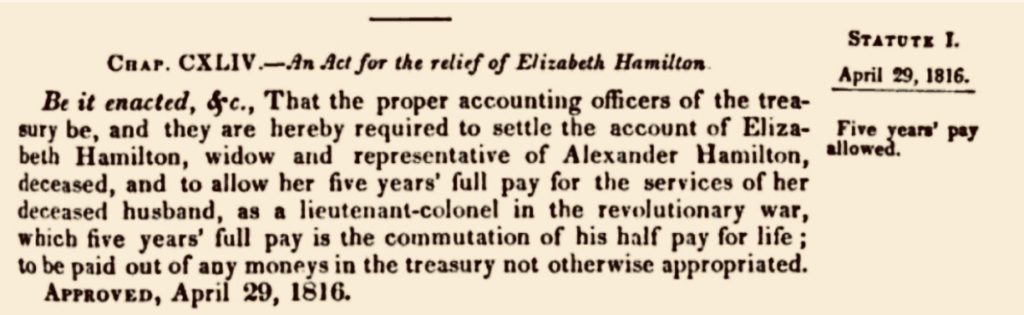

Thus, on April 2, 1816, almost twelve years after his death, Eliza was awarded a five year lump sum pension worth approximately $10,000. Copied below is the Act for the Relief of Elizabeth Hamilton, Chapter CXLIV of the Acts of the Fourteenth Congress, which passed on a vote of 84 to 30. Click here for the House Journal.

In 1839, Eliza and her adult children convinced the Twenty-Fifth Congress to award her land grants owed to Alexander. The “Act for the relief of the widow and other heirs at law of Alexander Hamilton, deceased” granted four hundred and fifty acres of land. Click here for a link to the Acts of the 25th Congress.

Perhaps most importantly, in 1846, Eliza successfully petitioned Congress for assistance with the publication of Hamilton’s papers. Click here for a link to Eliza’s handwritten petition. The petition explained that Alexander bequeathed to her “all of his public and private papers for publication as the only remaining legacy he had to bestow, having devoted his best energies to promote the general welfare.”

Eliza described that the papers embraced “the period of the War of Independence, the formation and the adoption of the federal constitution, the organization of the national government, with a full and satisfactory development of the foreign and domestic policy of Washington’s administration.”

Among other things, Eliza argued that the preservation of Hamilton’s papers would be found “essentially necessary to sustain and advance the dignity, glory, and welfare of the country. . .”

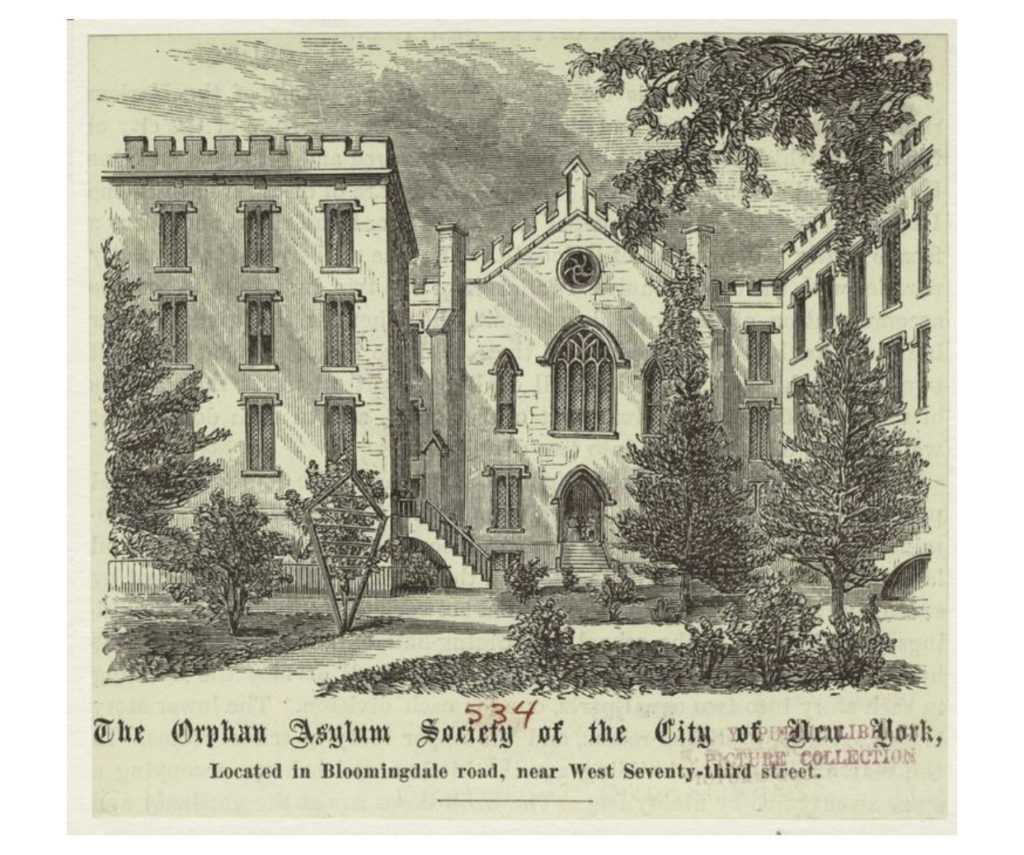

Subsequent posts will explore Eliza’s charitable works, including the establishment of New York’s first private orphanage in 1806. Established two years after Alexander’s death, the Orphan Asylum Society is the oldest non-profit and non-sectarian child welfare agency in America. Click here and here for a discussion of Eliza’s charitable works. She later worked with Dolley Madison and Louisa Adams to help raise money for the Washington Monument. At the ceremony to lay the cornerstone on July 4, 1848, she rode beside President Polk.