John Lewis and the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The nation lost a beloved civil rights icon with the recent passing of Congressman John Lewis. Lewis was engaged in nearly all of the pivotal events in the civil rights movement: the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins in 1960, the Freedom Rides in 1961, the March on Washington and Martin Luther King’s I Have A Dream Speech in 1963, the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, and the Bloody Sunday march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965. Perhaps his proudest achievement was the adoption of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (the “VRA”), which built upon the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The VRA of 1965 was one of the most effective civil rights laws in American history and arguably one of the most consequential laws ever passed by Congress. This two-part post attempts to recount the story of John Lewis’ struggle for the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. We are only beginning to understand the debt of gratitude that is owed to John Lewis and his allies who were not afraid to get into “good trouble, necessary trouble.”

Part I of this post discusses Lewis’ civil rights legacy leading into the historic March on Washington in 1963, his meeting with President Kennedy and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Part II continues with a discussion of Bloody Sunday and the adoption of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It was not by accident that the Voting Rights Act was introduced by President Johnson a week after John Lewis led the historic march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where he was almost killed by the Selma Police.

John Lewis was the son of sharecroppers, born into a family of ten children in rural Alabama. In 1957 he wrote to Dr. Martin Luther King and was invited to visit MLK in Montgomery.

Nashville Sit In Movement

As a student, Lewis organized sit-ins in segregated lunch counters in Nashville, resulting in his first arrest. The Nashville sit-ins were among the earliest direct action campaigns targeting racial segregation in the South.

As described by David Halberstam, then a reporter for The Nashville Tennessean:

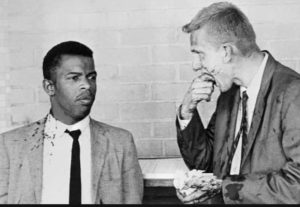

The protests had been conducted with exceptional dignity, and gradually one image had come to prevail — that of elegant, courteous young Black people, holding to their Gandhian principles, seeking the most elemental of rights, while being assaulted by young white hoodlums who beat them up and on occasion extinguished cigarettes on their bodies.

After three months of well-publicized lunch counter sit-ins, Nashville’s political and business leaders surrendered to Lewis’ non-violent tactics. Nashville thus became the first major Southern city to desegregate. Lewis’ work with the Nashville sit-in movement evolved into the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Freedom Riders and the Civil Rights Act of 1964

In 1961 Lewis was one of the 13 original Black and white Freedom Riders who sought to expose segregation in public transportation. The Freedom Rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and were designed to pressure the federal government to enforce Supreme Court decisions which were being ignored in the Jim Crow South.

The 1960 landmark case of Boynton v. Virginia held that segregation of bus terminals, restaurants and bathrooms was unconstitutional. The case was argued by Thurgood Marshall and built on the earlier case of Morgan v. Virginia, holding that segregation of interstate buses and trains was unconstitutional.

Lewis and his fellow activists traveled by bus from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans. Starting in South Carolina the Freedom Riders experienced horrific violence. For example, Lewis was rendered unconscious lying in a pool of blood outside the Greyhound Bus Terminal in Montgomery, Alabama.

When the Freedom Riders arrived in Anniston, Alabama, a mob firebombed their bus on May 14. Assured by local officials that they would look the other way, the KKK beat the passengers as they fled the burning bus.

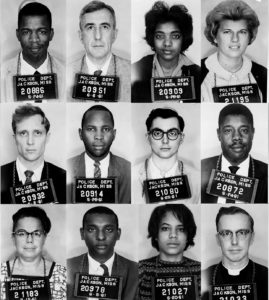

Rather than being protected by the police in Jackson, Mississippi, Lewis was arrested after he entered a “whites only” area of the city’s segregated bus station. Lewis spent 31 days in Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Penitentiary for “disorderly conduct.”

Over the next several months more than 60 additional Freedom Rides continued. Despite the danger, Lewis and the Freedom Riders blazed the path for the eventual adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On May 29, 1961, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to issue regulations banning segregation in interstate bus travel. Based on this request, effective November 1, 1961, the ICC required integration of buses and bus stations serving interstate travel, including water fountains and bathrooms.

Three years later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was adopted. The landmark law ended segregation in public facilities, provided for integration of schools, and made employment discrimination illegal.

The March on Washington and the 1963 “I Have a Dream Speech”

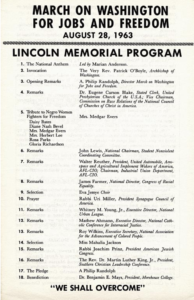

As chair of the SNCC, Lewis was one of the “Big Six” leaders who helped organize the 1963 March on Washington. More than 250,000 demonstrators assembled at the Washington Monument, where the rally began with celebrities and musicians. Participants then marched across the Mall to the Lincoln Memorial. The day ended with a meeting at the White House with the march leaders and President Kennedy.

At the age of 23, Lewis was the youngest speaker at one of the most important days in the history of the Civil Rights Movement. Lewis’ speech, which proceeded Martin Luther King’s I Have a Dream Speech, was the event’s most assertive address, vowing to keep marching “until the Revolution of 1776 is complete.”

Click here for the text of Lewis’ entire speech. Click here for a video of Lewis’ speech. The concluding paragraph is copied below:

They’re talking about slow down and stop. We will not stop. All of the forces of Eastland, Barnett, Wallace, and Thurmond will not stop this revolution. If we do not get meaningful legislation out of this Congress, the time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South; through the streets of Jackson, through the streets of Danville, through the streets of Cambridge, through the streets of Birmingham. But we will march with the spirit of love and with the spirit of dignity that we have shown here today. By the force of our demands, our determination, and our numbers, we shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in the image of God and democracy. We must say: “Wake up America! Wake up!” For we cannot stop, and we will not and cannot be patient.

Pictured below is John Lewis giving a speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Lewis is standing behind Martin Luther King at the White House, meeting with President Kennedy. Pictured left to right are Willard Wirtz (Secretary of Labor); Floyd McKissick (CORE); Mathew Ahmann (National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice); Whitney Young (National Urban League); Martin Luther King, Jr. (SCLC); John Lewis (SNCC); Rabbi Joachim Prinz (American Jewish Congress); A. Philip Randolph; Reverend Eugene Carson Blake; President John F. Kennedy; Walter Reuther (AFL-CIO); Vice President Lyndon Johnson; and Roy Wilkins (NAACP).

On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy addressed the nation to propose civil rights legislation. Click here for a link to Kennedy’s televised speech from the Oval Office. The following day Medgar Evers was assassinated in front of his home in Mississippi. President Kennedy submitted his civil rights bill to Congress the following week. It was immediately condemned by Southerners. Strom Thurmond described the bill as “unconstitutional, unwise and beyond the realm of reason.” Other Senators described the legislation as a “complete blueprint for the totalitarian state. . . “

The law was adopted in the House on February 10, 1964, but faced vocal opposition in the Senate. The “Southern Bloc” of 18 southern Democratic Senators led by Robert Byrd (D-WV) and Strom Thurmond (D-SC) filibustered for 54 days.

While Congress debated the bill, two tragic events occurred. On September 15, 1963, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, was bombed. Four young African-American girls died in the blast. On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was shot in Dallas. Two days after Kennedy was buried, President Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress to urge adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In one of his finest moments, Johnson argued in his November 27 speech that:

…No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long. We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights. We have talked for one hundred years or more. It is time now to write the next chapter, and to write it in the books of law.

The expansive Civil Rights Act of 1964 contains eleven titles. The most important provisions are described below:

- Title II: barred discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin in any public accommodation affected by interstate commerce (including restaurants, movie theaters, sports arenas, or other public accommodations);

- Title III: authorized the Attorney General to bring legal proceedings on behalf of others who lack funds or might feel that bringing suit on their own could jeopardize their safety or job;

- Title IV: sought active pursuit of desegregation in public schools and instructed the Attorney General to file suit to enforce the Act;

- Title VI: declared that any governmental entity receiving federal funds would lose those funds if it engaged in unlawful discrimination;

- Title VII: declared it unlawful for employers or unions to discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

This post continues in Part II which discusses Lewis’ march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday and the adoption of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Additional Reading:

March, John Lewis’ graphic novel

“John Lewis’ Arrest Records are Finally Uncovered,” Smithsonian Magazine (12/1/2016)

John Lewis Remembers His Arrest for Using a ‘White Bathroom’ 59 Years Ago, Newsweek

Martin Luther King’s legal legacy, Statutesandstories.com

C.T. Vivian, Martin Luther King’s Field General, Dies at 95, New York Times (7/17/2020)