John Lewis and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 [79 Stat. 437]

Congressman John Lewis was an icon of the Civil Rights Movement who went on to become the “Conscience of Congress.” Of all of his accomplishments Lewis was proudest of the adoption of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. According to Lewis, “the vote is the most powerful, non-violent tool we have in a democratic society.” He should know, since he nearly lost his life on the Edmund Pettus Bridge trying to secure voting rights.

Part 1 of this two-part post described Lewis’ work with the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins in 1960, the Freedom Rides in 1961, the March on Washington in 1963, culminating with the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

This post, Part 2, continues the story of the John Lewis’ legacy and the struggle for voting rights during the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, the Bloody Sunday march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (the “VRA”). Referred to as the “Crown Jewel” of the Civil Rights Movement, the VRA sought to fulfill the promise of the 15th Amendment which remained empty words for almost a hundred years.

Freedom Summer of 1964

The Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964 was a turning point for the Civil Rights Movement. The Freedom Summer combined a state-wide voter registration campaign with community action programs, using college students to expose life in the Jim Crow South.

As President of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lewis coordinated SNCC’s efforts to recruit and organize volunteers for the Freedom Summer project, along with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the NAACP and other affiliated groups. As part of the Freedom Summer (also known as the Mississippi Freedom Summer project), SNCC opened Freedom Schools and Freedom Houses to train and house volunteers from across the nation.

Mississippi was specifically selected as the location for the Freedom Summer project due to its historically low level of African-American voter registration. Less than 7 percent of the state’s eligible Black voters were registered to vote in 1962. Mississippi was also the state where NAACP civil rights organizer Medgar Evers was assassinated in front of his home in 1963.

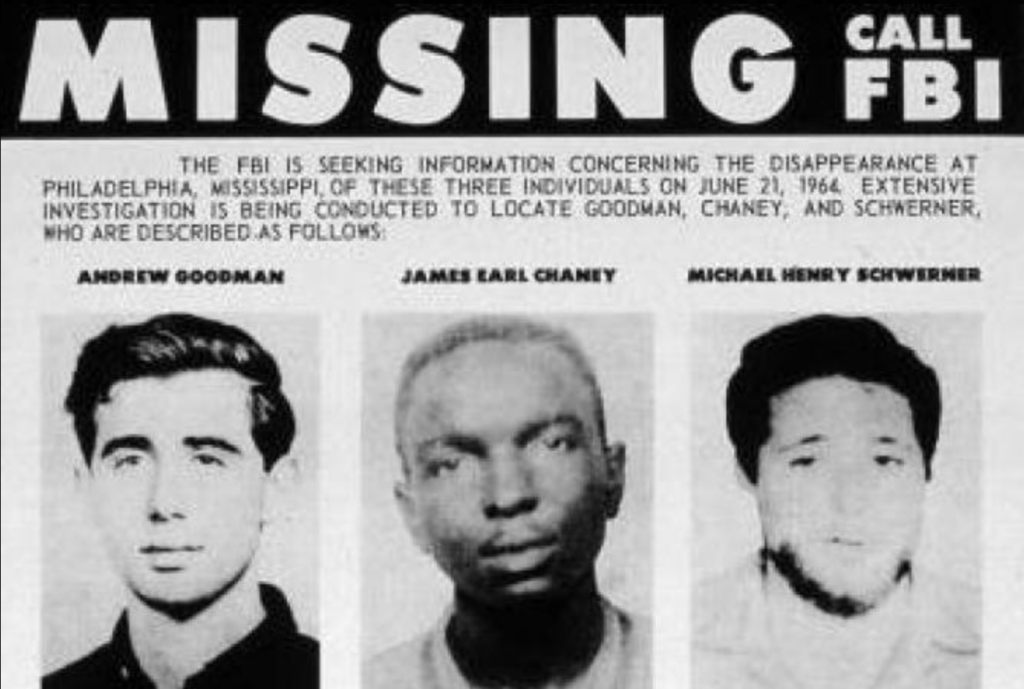

Among the first northern volunteers arriving for the Freedom Summer campaign were two New Yorkers, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, who teamed up with James Chaney, a local African-American student. The three disappeared after visiting Philadelphia, Mississippi, where they were investigating the burning of a church. The movie Mississippi Burning is based on the investigation of Goodman, Schwerner and Chaney’s murder.

As described by Lewis:

As chairman of SNCC, I worked with organizers from a federated council of civil rights organizations. I traveled all around the country talking to students asking them to participate in Freedom Summer, and they came from everywhere. They had witnessed and admired the struggle for human dignity waged all across the South through sit-ins and non-violent protests. They wanted to be a part of something greater than themselves.

Andrew Goodman and Mickey Schwerner were two of the students I met, and both were committed to the creation of a more inclusive democracy. James Chaney was a native of Mississippi who had been involved in civil rights work there in the months leading up to Freedom Summer. He volunteered to serve as a guide to help Goodman and Schwerner navigate the intricate landscape of Mississippi.

In July of 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. While Title I of the Civil Rights Act attempted to require equal application of voter registration requirements, critics asserted that the law did not go far enough. In 1965, John Lewis and his colleagues proved that this was the case in Alabama.

1965 Selma March and Bloody Sunday

As feared, the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was inadequate to fully protect voting rights in the Deep South. George Wallace had been elected Governor of Alabama on a blatantly segregationist platform in 1962. During his inaugural address, Wallace defiantly promised, “Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!” President John F. Kennedy was forced to deploy National Guard troops to desegregate the University of Alabama in 1963.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), chaired by John Lewis, were not afraid to enter the lion’s den. In early 1965, they targeted Dallas County, Alabama for a voter registration campaign that they anticipated would generate national attention. Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark famously wore a “Never” button and routinely carried a cattle prod and billy club.

Despite repeated efforts by local activists to register voters in Selma, Black voters were only two percent of the voting rolls, but over half of the population of Dallas County. The SLCC selected Selma for its campaign, fully anticipating that Governor Wallace and Sheriff Jim Clarke would resist their efforts. Doing so would put pressure on President Johnson to move ahead with a Voting Rights Act. Lewis and his allies could not have been more correct.

When it began in January of 1965, the voter registration campaign in Dallas County was resisted with mass arrests. In Selma and surrounding areas, Dr. King and three thousand other peaceful demonstrators were thrown in jail. But in February, Jim Crow turned violent.

On February 18, 1965, Alabama state troopers together with local police forcefully broke up a peaceful march in Marion, near Selma. During the confrontation, Jimmie Lee Jackson, a 26-year-old church deacon, was killed by state troopers. When he was shot, Jackson was merely attempting to protect his mother, who was being beaten by state troopers.

In response to Jackson’s death, a 54-mile march was planned from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery. Governor Wallace ordered state troopers “to use whatever measures are necessary” to prevent the march.

John Lewis from SNCC and Hosea Williams of SCLC led the March 7 march, which has become one of the most famous moments in the Civil Rights Movement. Approximately 600 activists departed from the Brown Chapel AME Church on March 7. Having received death threats, Dr. Martin Luther King decided not to attend. During the prior week, Dr. King had met with President Lyndon Johnson. Dr. King planned to arrive the following day in Selma.

Marching two-by-two, the marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus bridge. Alabama State Troopers commanded by Major John Cloud and Sheriff Jim Clark, backed by a phalanx of mounted deputies, were waiting for them.

Cloud ordered the marchers to turn around and go home. When the marchers did not immediately comply, Clark commanded his mounted posse to charge. During the “Bloody Sunday” assault, the peaceful marchers were chased back over the bridge. Over fifty patients would be treated at local hospitals, including John Lewis who suffered a fractured skull.

That evening, ABC interrupted its Sunday night movie – Judgment at Nuremberg – to show a fifteen-minute clip of the footage from Selma. Approximately 48 million Americans are believed to have viewed the unprovoked brutality which shocked the nation. In the next few days, hundreds of supporters poured into Selma to show support for the marchers.

On March 11, a white Unitarian minister, Rev. James Reeb, was killed in Selma by segregationists. Hundreds of civil rights demonstrators began picketing outside the White House to convince President Johnson to move ahead with a Voting Rights Act.

Additional marches followed. President Johnson sent 3,000 federal troops to Selma. He also federalized the Alabama National Guard to protect the marchers.

On March 17, U.S. District Court Judge Frank Johnson ruled that the state of Alabama was prohibited by the First Amendment from interfering with peaceful marches. John Lewis testified in the case about the March 7 attack, which is now known as Bloody Sunday. On March 25, 25,000 marchers led by Dr. King and John Lewis marched into Montgomery.

On March 15, Johnson convened a joint session of Congress and gave one of his most memorable speeches. In Johnson’s We Shall Overcome address, he quoted the catch phrase of the Civil Rights Movement and urged Congress to adopt the Voting Rights Act:

I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of Democracy. I urge every member of both parties, Americans of all religions and of all colors, from every section of this country, to join me in that cause.

At times, history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama. There, long suffering men and women peacefully protested the denial of their rights as Americans. Many of them were brutally assaulted. One good man–a man of God–was killed.

…In our time we have come to live with moments of great crisis. Our lives have been marked with debate about great issues: issues of war and peace, issues of prosperity and depression. But rarely in any time does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself. Rarely are we met with a challenge, not to our growth or abundance, our welfare or our security, but rather to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved nation.

The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation.

…But even if we pass this bill the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it’s not just Negroes, but really it’s all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.

And we shall overcome.

Click here for link to JBJ’s speech.

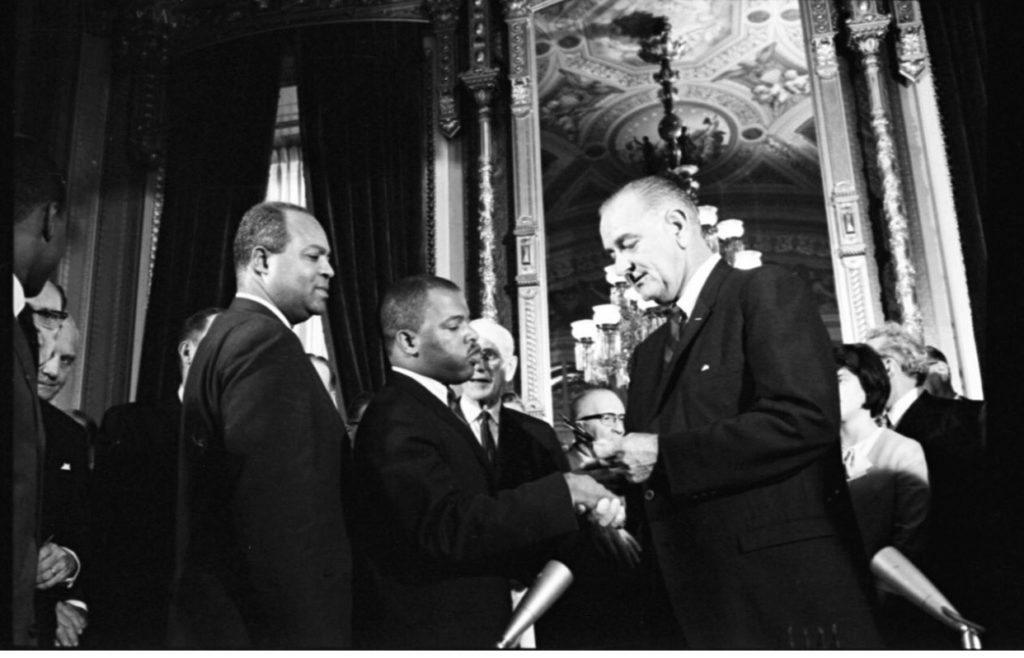

When President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6, he noted that the day was “a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield.” Pictured below is John Lewis and President Johnson at the signing ceremony.

Voting Rights Act of 1965

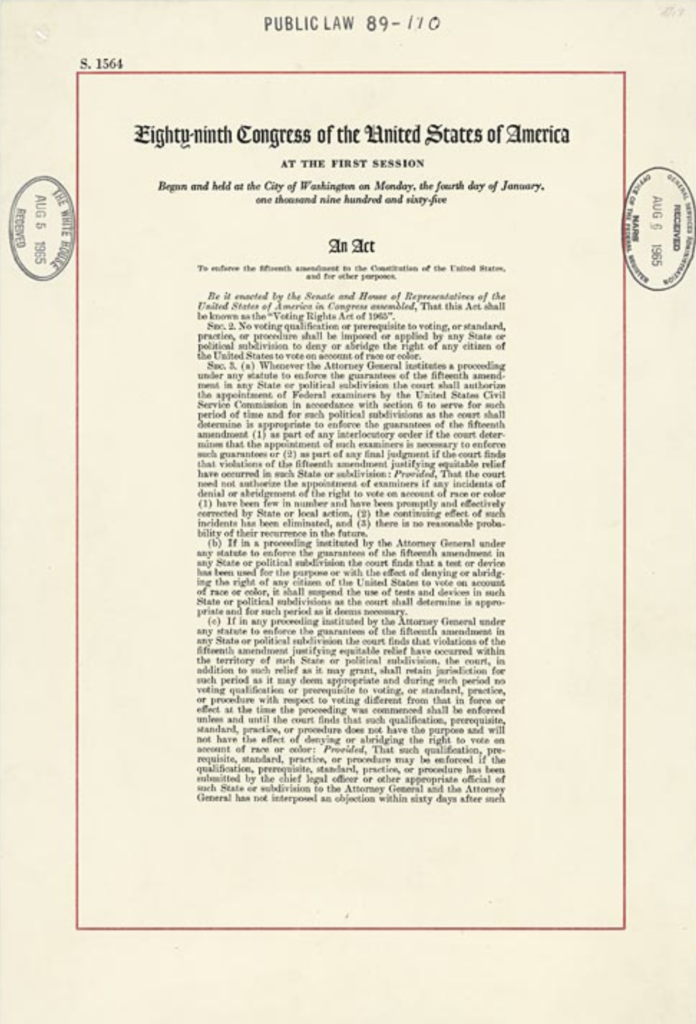

Formally titled as an “Act to enforce the 15th Amendment to the Constitution”, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) was a landmark accomplishment of the Civil Rights Movement. It became law ninety-five years after the 15th Amendment was ratified following the Civil War.

The VRA builds on the text of the 15th Amendment to outlaw literacy tests and other discriminatory practices that interfere with voting rights. Among other things, the Act provides that:

- Section 2: no voting qualification, standard or practice shall be imposed “to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

- Section 3: provides for the appointment of Federal examiners (with the power to register qualified citizens to vote) in “covered” jurisdictions according to a formula in the Act.

- Section 4: outlaws literacy tests.

- Section 5: requires covered jurisdictions to obtain “pre-clearance” for any new voting procedures from either the District Court for the District of Columbia or the U.S. Attorney General.

- Section 11: makes it a crime for any person to interfere with voting rights.

The 24th Amendment abolished the use of poll taxes in federal elections in 1964. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 directed the Attorney General to challenge the use of poll taxes in local elections. In Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966), the Supreme Court held that local poll taxes are unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment.

The Voting Rights Act had an immediate impact. By the end of 1965, a quarter of a million new Black voters had been registered, one-third by Federal examiners under the VRA. By 1967, more than half of all African American citizens were registered to vote.

As arguably the most significant change in the relationship between the Federal government and the states since Reconstruction, the Voting Rights Act was quickly challenged by its opponents in the courts. Between 1965 and 1969, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Section 5 and affirmed the Act’s pre-clearance requirements. See South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 327-28 (1966) and Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969).

Years later, in 2013, the Supreme Court struck down the VRA’s pre-clearance formula in Shelby County v. Holder. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court observed that Congress had the power to establish a substituted, replacement formula. According to John Lewis, Section 5 was the “heart and soul” of the law.

In 2011 President Obama awarded John Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. During the White House ceremony, President Obama said that, “Generations from now, when parents teach their children what is meant by courage, the story of John Lewis will come to mind — an American who knew that change could not wait for some other person or some other time; whose life is a lesson in the fierce urgency of now.”

As of the date of this post, a petition to rename the Edmund Pettus Bridge in John Lewis’ honor is pending. Pettus was a Confederate General and Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan, prior to be elected to the United States Senate in 1896.

It is important to recognize that the Civil Rights Movement had many leaders and heroes. For example, C.T. Vivian was known as Martin Luther King’s “Field General”. Vivian was punched in the face by Sheriff Clark on the steps of the Dallas County courthouse in February of 1965, one month prior to the Bloody Sunday march. Both Lewis and Vivian passed away on July 17th. They will be missed, but their legacy will march on.

Additional Reading:

Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Library of Congress)

On this day, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is signed (National Constitution Center)

Case Study: The Selma Conflict, Colleen Fleming, Stanford University

The Selma to Montgomery March (MLK Research and Education Institute)