Presidential Election Day Act of 1845 [5 Stat. 721, 28th Congress, Session 2, Chapter I]

Like clockwork, American Presidential elections have been held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday of November since Zachary Taylor was elected President in 1848. The “Act to establish a uniform time for holding elections for electors of President and Vice President in all the States of the Union”, otherwise known as the “Presidential Election Day Act,” was adopted on January 23, 1845. It has become of one of the most well established features of Presidential elections for the past 175 years.

As required by the Presidential Election Day Act, Presidential elections are uniformly held across the county every four years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday of November. The members of the Electoral College formally vote in their state capitals on the first Monday after December 12. Congress certifies the election results in a Joint Session held on January 6. The President is inaugurated on January 20.

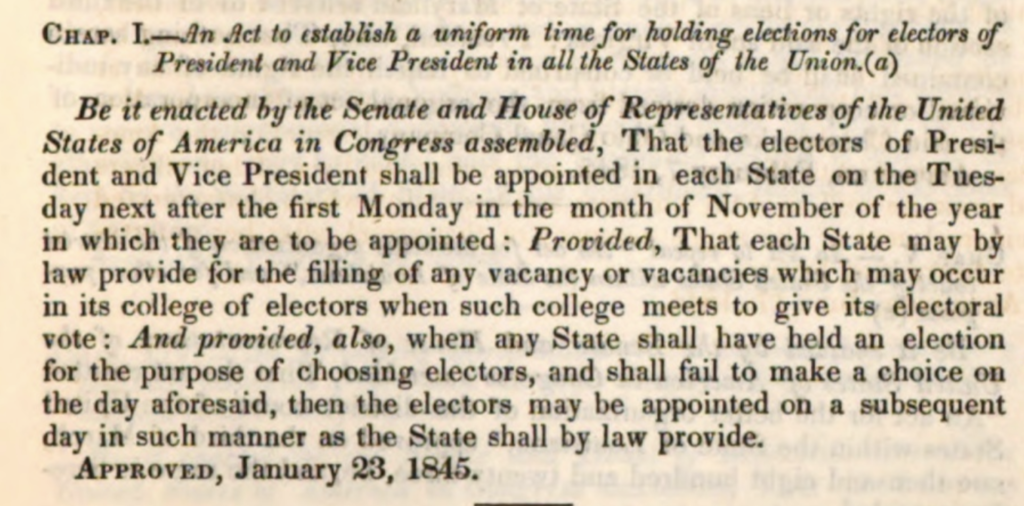

Despite its lengthy official name, the Presidential Election Day Act is relatively simple. The Act consists of a single paragraph which is pictured below in its entirety. The Act provides that Presidential elections shall be held “on the Tuesday next after the first Monday in the month of November”. The Act was adopted by the 28th Congress in January of 1845, following the Presidential election of 1844.

Constitutional Requirements

Originally, the Constitution delegated the conduct of national elections to the states. It was difficult enough for the framers to draft the Constitution during the long summer of 1787. Many details were left to be hammered by Congress, which was authorized – but not required – to determine the time for federal elections. From 1787 until 1844, Congress allowed individual states to select election dates in their respective jurisdictions.

Article I, Section 4, clause 1 grants state legislatures the ability to set the “times, places and manner” of holding elections for Congress, unless Congress elects to act:

The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.

Article II, Section 1, clause 4 governs Presidential elections but merely provides as follows:

The Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States (emphasis added)

Thus, in the early years of the Federal government, states were responsible for selecting the date for local and national elections. This default procedure was used through 1844 and resulted in a patchwork of elections held at different times. Eventually it became clear in the 1840’s that this procedure was problematic.

Knowledge of voting results in early voting states could affect voter turnout. In a close election, later voting states and last-minute voters had the power to to sway the outcome of the entire election. The large window to conduct elections across the states also enabled voter fraud.

Elections of 1840 and 1844

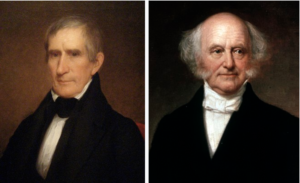

In the 1840 Presidential election, incumbent President Martin Van Buren was was defeated by popular war hero William Henry Harrison. Known for his victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe, Harrison had a broad appeal to common voters and farmers against the more detached Van Buren, who was perceived as too aristocratic. Up to 80% of eligible voters turned out, driven by large rallies, parades, songs, posters and the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler too.”

The nation was suffering through a depression and President Van Buren only carried seven states. Yet, Van Buren still received 400,000 more popular votes than any prior presidential candidate, as the total number of votes cast increased from 1.5 million in 1836 to 2.4 million in 1840.

The 60% expansion in the size of the popular vote between 1836 to 1840 is the largest proportional increase between consecutive elections in American history. Much of the increase can fairly be attributed to increased voter turnout due to new campaign techniques and a heated campaign. But, it is believed that voter fraud may also have played a role.

One method of voter fraud was enabled by the fact that different states held their elections on different days. For example, in 1844 voting occurred in different states from November 1 through December 4. As a result, “floaters” were able to cross state boundaries to vote in another state after voting in their own state. Another name for this practice was “pipe-laying,” because if the floaters were challenged they were instructed to reply that they were in town to lay pipes. “Repeaters” were voters who changed their clothes and otherwise altered their appearance to vote in different precincts. This was possible in a day when voter registration was not required. Click here for the House debate contained in the Congressional Globe.

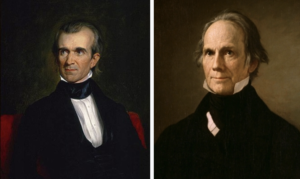

Four years later, during the election of 1844, Democrat James Polk defeated Whig party candidate Henry Clay. Irish, Catholic and new immigrant voters turned out in large numbers to support Polk. Clay’s running mate, Theodore Frelinghuysen, alienated these groups when he reportedly gave “his head, his hand, and his heart” to temperance and other Protestant causes. On the night before the election, so many new Irish voters marched to the courthouse in New York to qualify to vote that the windows had to be used as exits. Whigs complained that, “Ireland has reconquered the country that England lost.”

First Tuesday after the first Monday

Modern voters justifiably wonder why election day is held on a Tuesday. In the 19th Century, when the nation was largely agrarian, a middle of the week election day made sense.

When the Presidential Election Day Act was adopted in 1845 large percentages of the electorate were farmers who often had to travel long distances to vote. Weekends were impractical when many voters spent Sundays in church. It was also common for farmers to sell their crop at market from Wednesday through Friday.

Accordingly, Tuesday was the most convenient day of the week to hold elections. Similar reasons dictated the choice of November. Holding elections in the spring or early summer would interfere with the planting season. Holding elections in the late summer or early fall would interfere with the harvest. November was a sweet spot since the harvest would be complete, prior to the arrival of the coldest winter weather when travel would be more difficult.

Holding elections on the Tuesday “after the first Monday” was intended to prevent elections from falling on November 1, the Catholic holiday of All Saints Day. Moreover, November 1 was avoided as many merchants used the first day of the month for bookkeeping purposes and to settle accounts. This explains why election day can fall between November 2 to November 8 on different years.

Subsequent election laws and amendments

The Presidential Election Day Act of 1845 only applied to Presidential elections. In 1872, Congress extended the law to apply to elections for members of the House of Representatives. Coverage was extended to Senate elections by the 17th Amendment, which provided for the direct election of Senators in 1914.

The 12th Amendment modified the procedure for the selection of Vice President in 1804. Click here for a discussion of the Election of 1800. While the 12th Amendment was an important revision to the Electoral College, it did not change the dates of federal elections, which continued to be set by the states until the Presidential Election Day Act of 1845.

The 20th Amendment ratified in 1933 provides that Presidential and Vice Presidential terms expire on January 20 at noon, when their successor’s terms begin. The 20th Amendment further provides that each new Congress shall convene at noon on January 3 in each odd-numbered year, unless the prior Congress designates a different day, as follows:

Section 1. The terms of the President and Vice President shall end at noon on the 20th day of January, and the terms of Senators and Representatives at noon on the 3d day of January, of the years in which such terms would have ended if this article had not been ratified; and the terms of their successors shall then begin.

Section 2. The Congress shall assemble at least once in every year, and such meeting shall begin at noon on the 3d day of January, unless they shall by law appoint a different day.

In addition to these constitutional deadlines, Congress by statute controls when electoral votes are counted. The law currently provides that “the electors of President and Vice President of each State (the Electoral Congress) shall meet and give their votes on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December next following their appointment at such place in each State as the legislature of such State shall direct.”

Recent proposals

Following the September 11 terrorist attack, contingency plans have been studied in the event of a national emergency. Given the shift in the American economy away from agriculture, bills were introduced in the House to move Presidential Election Day to the weekend. While the bill has gathered support in the House it has stalled in the Senate. Others have proposed making Presidential Election Day a national holiday.

Prior to the 2020 election, President Trump tweeted that the Covid-19 epidemic might be grounds to delay Presidential Election Day. This suggestion was roundly rejected. In order to revise the date, Congress would need to act. Moreover, the Tuesday date has remained fixed since 1845. Indeed, no federal election has ever been rescheduled in response to an emergency. Americans voted in regularly scheduled elections during the Civil War, the Great Depression, and both World Wars.

Professor Richard Pildes has suggested that the so-called “failed election” provision of the Election Day Act is outdated and should be removed. Codified in 3 U.S.C. § 2, the failed election clause provides as follows:

Whenever any State has held an election for the purpose of choosing electors, and has failed to make a choice on the day prescribed by law, the electors may be appointed on a subsequent day in such a manner as the legislature of such State may direct.

According to Pildes, this provision is a “dangerous loaded weapon” since the Election Day Act does not define what it means for an election to have “failed.” While the provision has never been invoked, President Trump pursued a strategy after the 2020 election of calling upon governors and swing state legislatures to appoint presidential electors, overriding the popular vote.

Pildes explains that, “It is the only place in federal law that identifies circumstances in which, even after a popular vote for president has been taken, a state legislature has the power to step in and appoint electors.” Because the original purpose of the “failed election” provision no longer applies, Pildes suggests that the law be modernized to shore up the foundation of American democracy.

Court Challenges in 2020

Following the 2020 Election, President Trump argued that the election was a “failed election” under the 1845 Act (3 U.S.C. § 2). In the case of Trump v. Wisconsin Election Commission the President’s lawyers alleged that the failure to comply with Wisconsin law resulted in a failed election, which would open the door for the Wisconsin Legislature to appoint its own slate of Presidential Electors. Under the President’s legal theory, a failed election violated the “Elector’s Clause” in Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution (providing that “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct…”).

Federal District Court Judge Brett Ludwig (a Trump appointee) rejected this argument on the merits and dismissed the case on December 12, 2020. In a detailed opinion, Judge Ludwig concluded that the President failed to show a clear departure from Wisconsin election law, established by the Wisconsin Legislature. As such, there was no constitutional violation to be addressed in federal court:

Plaintiff’s Electors Clause claims fail as a matter of law and fact. The record establishes that Wisconsin’s selection of its 2020 Presidential Electors was conducted in the very manner established by the Wisconsin Legislature, “[b]y general ballot at the general election.” Wis. Stat. §8.25(1). Plaintiff’s complaints about defendants’ administration of the election go to the implementation of the Wisconsin Legislature’s chosen manner of appointing Presidential Electors, not to the manner itself. Moreover, even if “Manner” were stretched to include plaintiff’s implementation objections, plaintiff has not shown a significant departure from the Wisconsin Legislature’s chosen election scheme.

This is an extraordinary case. A sitting president who did not prevail in his bid for reelection has asked for federal court help in setting aside the popular vote based on disputed issues of election administration, issues he plainly could have raised before the vote occurred. This Court has allowed plaintiff the chance to make his case and he has lost on the merits. In his reply brief, plaintiff “asks that the Rule of Law be followed.” (Pl. Br., ECF No. 109.) It has been.

Click here for a link to Judge Ludwig’s order.

Additional reading:

Election laws (National Archives)

Postponing Federal Elections Due to Election Emergencies, Michael Morley

Executive Branch Power to Postpone Elections (Congressional Research Service)