Impeachment of a former President (Part 2)

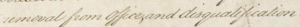

Following the events of January 6, 2021, several previously theoretical constitutional issues are no longer merely academic questions. The Constitution clearly provides that impeached officeholders are subject to removal from office when convicted. Yet, the Constitution does not explicitly address the threshold jurisdictional issue of whether a defendant must still be in office at the time of the Senate trial.

The following post (Part II) explores the power of Congress to check a President with “late term” or “post term” impeachment. Similar to the issue of self pardons, the Constitution does not directly address whether impeachment may occur following a Presidential resignation (or after the expiration of a Presidential term). Nevertheless, the Constitutional framework, its well documented drafting history, the ratification debates, and subsequent precedents offer answers.

Part I of this post summarized the Constitution’s text and discussed the role of Presidential pardons as envisioned by the framers of the Constitution. While the Constitution does not prevent self pardons, the framers constructed a rigorous system of checks and balances. As such, the framers recognized that an underlying rationale supporting the rule of law was the long established maxim that “no one may be a judge in his own case.”

The following post (Part II) explores the power of Congress to check a President with “late term” or “post term” impeachment. Similar to the issue of self pardon, the Constitution mentions impeachment six times, but does not directly address whether impeachment may occur following a Presidential resignation or after the expiration of a Presidential term.

While modern scholars can be found on both sides of this issue, according to the Congressional Research Service the greater weight of authority supports the ability of the Senate to hold an impeachment trial at a time of its choosing. This is particularly the case if the President was impeached by the House while still in office.

This post begins with a review of the applicable Constitutional provisions. After setting forth the underlying text, it is useful to analyze four different impeachment scenarios that help frame the discussion. The scholarly arguments for and against post-term impeachment are then addressed, along with a high level summary of passages from the Federalist Papers. Lastly, precedents where the Senate has conducted post-term impeachment are discussed.

Ultimately only the Supreme Court can definitively answer this question when and if it is raised as a defense by former President Donald J. Trump. Yet, based on the 1993 case of Walter Nixon v. United States, it is unlikely that the Supreme Court will answer this “political question.” The Nixon case held that the procedure used by the Senate to conduct an impeachment trial is a non-judicable question vested solely in the Senate’s discretion. If so, the Senate will need to decide for itself how to interpret and apply its impeachment powers when conducting a post-term impeachment.

Applicable Constitutional Text

The Congressional power of impeachment is primarily discussed in Article I, but is also mentioned in Article II and III. A prior post (Part I) provides a full listing of all Constitutional provisions relating to impeachment. Copied below are the handful of applicable provisions that bear on the issue of post-term impeachment:

The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. (Art. I, §2)

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present. (Art. I, §3)

Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law. (Art. I, §3)

Impeachment is also briefly mentioned in Article II:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors. (Art. II, §4)

Charting Presidential Impeachment Scenarios

Conceptually, a Presidential impeachment could arise in several contexts. Professor Brian Kalt identifies four scenarios involving both pre and post-Presidential impeachment. The following chart analyzes impeachment based on the timing of two questions:

- Date of impeachment: Whether the President is currently in office at the time of the impeachment trial?

- Date of offense: Whether the President was in office when the office occurred?

Scenario 1 involves a serving President who committed the impeachable offense while in office. To date, all Presidential impeachments in American history have fallen under Scenario 1.

Scenario 4 is the polar opposite case of a former President who committed the offense out of office (either before or after his or her term). Scenario 4 is the most controversial and weakest of the four possible cases. By allowing impeachment unconnected to federal office, Scenario 4 would likely run afoul of Article II, §4 of the Constitution which provides for impeachment of the “President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States” who shall be “removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

Scenario 3 involves impeachment of a sitting President for conduct occurring prior to taking office. Deterring election fraud that used to win office is an example of why Scenario 3 is likely Constitutional.

Scenario 2 involves impeachment of a former President for an offense committed while in office. While it is true that Article II, §4 provides for removal from office, Article I, §3 provides that “[j]udgment in cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office office of honor, trust, or profit under the United States.”

Accordingly, the Senate has two important decisions to make in each case of impeachment: (i) whether to convict and remove; and (ii) whether the impeached President should be disqualified from holding future office. In fact, of the eight impeachments where the Senate voted to convict, it only voted to disqualify three from holding future office. This result reinforces the conclusion that removal and disqualification are separate and distinct inquiries.

Analytically, all four Presidential impeachments in American history through 2020 involved Scenario 1 (Andrew Johnson, Nixon, Clinton and Trump 1). The “Trump 2” impeachment in 2021 will involve Scenario 2 as the Senate trial will take place post-Presidency. Because the insurrection against the Capitol occurred while Trump was President, it is not a problematic Scenario 4 impeachment.

Of course, impeachment is not limited to Presidents and can be brought against any federal “civil officer.” Since the term “civil officer” is not defined by the Constitution, the timing of the offense and the timing of the trial are subject to debate.

According to Professor Kalt, basing Congressional jurisdiction on the status of the offender at the time of the offense reinforces the notion that impeachment is limited to offenses committed by public officers, as officers. This interpretation is consistent with the scope of the impeachment power found in the state constitutions written prior to 1787. This interpretation is also consistent with Hamilton’s description of the purpose of impeachment in Federalist 65 which focused on “the misconduct of public men” and the “abuse or violation of some public trust.”

The Arguments in Favor of Post-Term Impeachment

On January 21, 2021, more than 150 leading constitutional scholars wrote an open letter expressing their opinion that post-term impeachment is constitutional. The signatories, which include members of the conservative Federalist Society, are careful to avoid taking a position on whether President Trump should be convicted. Thus the letter only discusses the constitutional question of Senate jurisdiction.

The well respected scholars signing the letter include: Steven Calabresi (co-founder of the Federalist Society), Charles Fried (solicitor general under Ronald Reagan); Ilya Somin (law professor at George Mason University and libertarian Cato Institute scholar); Brian Kalt (a leading scholar on impeachment), and Lawrence Tribe (outspoken constitutional law expert and emeritus professor at Harvard Law School).

The letter begins by acknowledging the authors’ differing political outlooks:

We differ from one another in our politics, and we also differ from one another on issues of constitutional interpretation. But despite our differences, our carefully considered views of the law lead all of us to agree that the Constitution permits the impeachment, conviction, and disqualification of former officers, including presidents.

Summarizing its conclusion, the letter explains that its analysis is based on “the text and structure of the Constitution, the history of its drafting, and relevant precedent.” Importantly, the letter reasons that the Constitution’s impeachment power has two separate components which each need to be given “full effect.”

The first is removal from office, which occurs automatically upon the conviction of a current officer. The second is disqualification from holding future office, which occurs in those cases where the Senate deems disqualification appropriate in light of the conduct for which the impeached person was convicted.

While admitting that impeachment is the exclusive constitutional means of removing a President from office, the scholars emphasize that nothing in the Constitution limits impeachment to currently serving Presidents:

But nothing in the provision authorizing impeachment-for removal limits impeachment to situations where it accomplishes removal from office. Indeed, such a reading would thwart and potentially nullify a vital aspect of the impeachment power: the power of the Senate to impose disqualification from future office as a penalty for conviction. In order to give full effect to both Article I’s and Article II’s language with respect to impeachment, therefore, the correct conclusion is that former officers remain subject to the impeachment power after leaving office, for purposes of permitting imposition of the punishment of disqualification.

According to the letter, a central rationale for post-term impeachment is the role of deterrence:

If an official could only be disqualified while he or she still held office, then an official who betrayed the public trust and was impeached could avoid accountability simply by resigning one minute before the Senate’s final conviction vote. The Framers did not design the Constitution’s checks and balances to be so easily undermined.

The letter also draws on history and past practice:

History supports a reading of the Constitution that allows Congress to impeach, try, convict, and disqualify former officers. In drafting the Constitution’s impeachment provisions, the Framers drew upon the models of impeachment in Great Britain and state constitutions. In 1787, English impeachment was understood to allow for the impeachment, trial, and conviction of former officials; likewise, the law of several states made clear that waiting to impeach officials until they were out of office was preferred or even required, and no state barred the impeachment of former officials.

Moreover, the letter argues that the founders were concerned with the risk of demagogues attempting to overthrow the government, which danger continues after a Presidential term:

The Framers further understood that the source of such a person’s power does not expire if he or she is expelled from office; so long as such a person retains the loyalty of his or her supporters, he or she might return to power. The Framers devised the disqualification power to guard against that possibility, and would surely disagree that a person who sought to overthrow our democracy could not be disqualified from holding a future office of the United States because the plot reached its crescendo too close to the end of his or her term.

Lastly, the letter cites to Congressional precedent:

In 1876, Secretary of War William Belknap tried to avoid impeachment and its consequences by resigning minutes before the House voted on his impeachment. The House impeached him anyway, and the Senate concluded that it had the power to try, convict, and disqualify former officers. Even in cases when impeachment proceedings were dismissed after the subject resigned, Congress has indicated that it was choosing to drop the case rather than being compelled to do so by the Constitution. Belknap was not a president, but there is no reason why the same rule would not apply to presidents—after all, the Constitution’s impeachment provisions apply to presidents, vice presidents, and civil officers alike.

Additional grounds for Senate jurisdiction which are not listed in the letter include the fact that Article I, §3 provides that “no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.” Definitionally, a former President is a “person” whether or not they are currently serving.

Expanding on the letter’s historical argument, it is noteworthy that both England and many of the state constitutions that predate the U.S. Constitution allowed post-term impeachment.

Beginning in 1776, ten of the newly independent states adopted constitutions that included impeachment provisions. Exactly half of these state constitutions specifically permitted late impeachment, while no state explicitly forbade it. The impeachment provisions in the state constitution in 1787 were collected by Professor Kalt in an exhaustive law review article which observes that the biggest dispute was over what body should try impeachments, not the timing of impeachment trials. According to Kalt, “in each constitution, late impeachment was either required, permitted, or not discussed, but nowhere explicitly forbidden.”

During the drafting of the Constitution the framers were aware of – and discussed – “the Hastings impeachment.” In fact, Parliament proceeded against Governor Warren Hastings in London while the framers were meeting in Philadelphia. Hastings was a former governor-general of India who retired two years before he was later impeached.

The House of Commons charged Hastings with a variety of criminal and non-criminal offenses, including confiscating land in India and provoking a revolt. The Hastings trial before the House of Lords proceeded while the American delegates met in Philadelphia.

Copied above is a portrait of Royal Governor Hastings. After his resignation he was replaced in India by Charles Cornwallis (the British General who was defeated at Yorktown). Pictured below is the protracted Hastings impeachment in Westminster Hall in 1788. Hastings was later acquitted by the House of Lords.

During the Constitutional Convention, Virginia delegate George Mason observed that Hastings was accused of abuses of power, not treason. Mason argued that the U.S. Constitution needed to guard against a President who might commit similar offenses. Years later the House of Lords finally acquitted Hastings in 1795.

As discussed in Part I, it was Mason who argued on June 20, 1787 that “No point is of more importance than that the right of impeachment should be continued. Shall any man be above Justice?” James Madison similarly described impeachment as “indispensable . . . for defending the Community [against] the incapacity, negligence or perfidy of the chief Magistrate.” Massachusetts delegate Elbridge Gerry claimed that impeachment was necessary as a check against abuses of power. “A good magistrate will not fear [impeachments]. A bad one ought to be kept in fear of them.”

On September 8, 1787, after considering the Hastings example, George Mason convinced the American delegates to substitute the British phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors” in place of the term “maladministration.”

The Arguments Against Post-Term Impeachment

Perhaps the strongest critic of post termination impeachment is retired Fourth Circuit Court of Appeal Judge J. Michael Luttig. In an Op-Ed in theWashington Post, the highly regarded conservative jurist argued that “Once Trump leaves office, the Senate can’t hold an impeachment trial.” According to the strict constructionist judge, after Trump leaves office “Congress loses its constitutional authority to continue impeachment proceedings against him — even if the House has already approved articles of impeachment.”

Luttig explained that:

The reason for this is found in the Constitution itself. Trump would no longer be incumbent in the Office of the President at the time of the delayed Senate proceeding and would no longer be subject to “impeachment conviction” by the Senate, under the Constitution’s Impeachment Clauses. Which is to say that the Senate’s only power under the Constitution is to convict — or not — an incumbent president.

For Luttig, the “purpose, text and structure” of the Impeachment Clause confirm this “intuitive and common-sense” interpretation. Luttig argues that “[t]he very concept of constitutional impeachment presupposes the impeachment, conviction and removal of a president who is, at the time of his impeachment, an incumbent in the office from which he is removed.”

Luttig asserts that the purpose of the impeachment power is to remove the President or other “civil official” from office before they could further harm the nation. Luttig cites to Article II, Section 4 which refers to the President, being “removed from Office” and Article I, Section 3 which indicates that “Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States.”

Luttig disagrees with the suggestion that the Senate could proceed to trial in an effort to disqualify the President from holding future public office. For Luttig, this is incorrect “because it is a constitutional impeachment of a president that authorizes his constitutional disqualification.” If a president has not been constitutionally impeached, then the Senate is without the constitutional power to disqualify him from future office.

After Judge Luttig’s Op-Ed, several noteworthy rebuttals argued that the Senate has the power to convict a former President. Here is a link to Laurence Tribe’s Op-Ed in the Washington Post.

In addition to Judge Luttig’s textual arguments based on a narrow reading of the Impeachment Clause, it is anticipated that President Trump’s defenders in the Senate will argue that a Scenario 2 impeachment is a “slippery slope” to the use of impeachment as a weapon to attack political rivals. For example, Trump’s defenders might cite to Hamilton’s concern in Federalist 65 that impeachment “will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused.” This “weaponization” argument would be more of a concern for Scenario 4 impeachment. The Trump 2 impeachment involves conduct that occurred while he was President under Scenario 2 and thus a future slippery slope is in the eye of the beholder.

Federalist Papers:

The founders had confidence in the unimpeachable integrity of George Washington. They had less confidence in future office holders, which is why they created an intricate overlapping, self-reinforcing structure of separation of powers and checks and balances. In Federalist 51, Madison famously explained that government is necessary because men are not angels:

If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.”

Madison described the importance of checks and balances, which the framers considered fundamental to the Constitution’s design:

We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power, where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights.

In Federalist 27 Hamilton emphasized the importance of accountability as a guard against sedition. While Hamilton was not discussing impeachment per se, it is clear that he was concerned about the risks of unchecked “impunity,” which for Hamilton was a “strong incitement to sedition”:

The hope of impunity is a strong incitement to sedition; the dread of punishment, a proportionably strong discouragement to it. Will not the government of the Union, which, if possessed of a due degree of power, can call to its aid the collective resources of the whole Confederacy, be more likely to repress the FORMER sentiment and to inspire the LATTER, than that of a single State, which can only command the resources within itself? A turbulent faction in a State may easily suppose itself able to contend with the friends to the government in that State; but it can hardly be so infatuated as to imagine itself a match for the combined efforts of the Union. If this reflection be just, there is less danger of resistance from irregular combinations of individuals to the authority of the Confederacy than to that of a single member.

Hamilton repeats the broader point in Federalist 70 that every magistrate (including the President) ought to be personally responsible for their behavior.

But in a republic, where every magistrate ought to be personally responsible for his behavior in office the reason which in the British Constitution dictates the propriety of a council, not only ceases to apply, but turns against the institution. In the monarchy of Great Britain, it furnishes a substitute for the prohibited responsibility of the chief magistrate, which serves in some degree as a hostage to the national justice for his good behavior. In the American republic, it would serve to destroy, or would greatly diminish, the intended and necessary responsibility of the Chief Magistrate himself.

Indeed, as acknowledged by Hamilton, the British system of impeachment was the model that the founders had in mind when they drafted the Constitution. Modern scholars who argue that post-term impeachment is constitutional similarly cite to the British system as a precedent.

This aligns with the underlying purpose of impeachment. As described by Hamilton in Federalist 65 impeachment is directed to the “misconduct of public men” involving “an abuse of violation of some public trust.” Hamilton acknowledged the risk, however, that prosecution of a President would “agitate the passions” of the populace:

A well-constituted court for the trial of impeachments is an object not more to be desired than difficult to be obtained in a government wholly elective. The subjects of its jurisdiction are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself. The prosecution of them, for this reason, will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused. In many cases it will connect itself with the pre-existing factions, and will enlist all their animosities, partialities, influence, and interest on one side or on the other; and in such cases there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.

Belknap and Blount Precedents

Since 1789, only 20 federal officials have been impeached by the House. Of the eight Senate trials, only three were convicted and removed by the Senate. The most famous example of late impeachment is the case of Secretary of War, William Belknap in 1876.

In an effort to beat out the clock, the corrupt Secretary of War raced to the White House to submit his resignation prior to the House impeachment vote. Rejecting this defense, the Senate specifically determined it had the right to try a former Cabinet member “for acts done as Secretary of War, notwithstanding his resignation of said office.” While a majority of the Senate voted to convict, Belknap avoided conviction when the Senate vote failed to obtain the necessary two-thirds threshold.

Despite Belknap’s acquittal, the House Managers interpreted the Belknap precedent as supporting Senate trials of former office holders:

[T]he managers believe that great good will accrue from the impeachment and trial of the defendant. It has been settled thereby that persons who have held civil office under the United States are impeachable, and that the Senate has jurisdiction to try them, although years may elapse before the discovery of the offense or offenses subjecting them to impeachment…. To settle this principle, so vitally important in securing the rectitude of the class of officers referred to, is worth infinitely more than all the time, labor, and expense of the protracted trial closed by the verdict of yesterday.

The first impeachment precedent under the U.S. Constitution occurred in 1798, a decade after the Constitution was ratified. While serving as Governor of the Tennessee Territory, William Blount conspired to give the British control over then-Spanish Florida and parts of French Louisiana. Blount was subsequently elected to the Senate.

After the plot was exposed, Blount was quickly impeached by the House and expelled from the Senate. At his impeachment trial, Blount’s lawyers argued that he could not be tried since he was no longer a sitting Senator. This argument was rejected. Ultimately Blount was acquitted by a vote of 14-11, on the basis that Senators are not Article II “officers” subject to impeachment.

Additional Reading:

Why Trump Can Be Convicted Even as an Ex-President, Stephen I. Vladeck, New York Times (1/14/2021)

The Founders Set an Extremely High Bar for Impeachment, Margaret Taylor, Atlantic (1/31/2021)

War Secretary’s Impeachment Trial (Senate.gov)

Constitutional Law Scholars – Open Letter on Impeaching Former Officers dated 1/21/2021

Legal Scholars, including at Federalist Society, say Trump can be convicted (Politico, 1/21/21)

The Debate Over the President (Center for the Study of the American Constitution)

The Impeachment and Trial of a Former President (Congressional Research Service, 1/15/21)