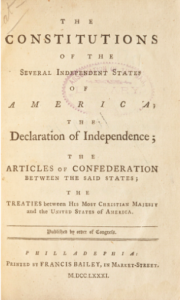

The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America, printed in 1781 by Francis Bailey

During the depths of the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress voted on December 29, 1780 to assemble and print 200 copies of America’s founding documents. This post describes the important work which was “published by order of Congress” in 1781 by Philadelphia printer Francis Bailey.

The “small volume” included a copy of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, the state constitutions, and the treaties between America and France. Referred to by rare book dealers as “America’s Magna Carta,” the 1781 publication was an announcement to the world that America was a new nation to be taken seriously, not merely a provincial rebellion.

Adams’ request to Congress from Amsterdam

Between 1777-1779, John Adams had served as the American envoy to France. In 1780, John Adams traveled to Amsterdam in an effort to secure loans and support from the Dutch. In a letter dated September 25, 1780, Adams wrote to the President of Congress and suggested that Congress print an official copy of the Articles of Confederation along with the state constitutions.

Adams explained that “[n]othing would Serve our cause more than having a compleat Edition of the American Constitutions, correctly printed in English, by order of Congress, and sent to Europe, as well as Sold in America.”

Adams suggested that along with the Articles, “[t]his Work would be read by every Body in Europe, who reads English, and could obtain it, and Some would even learn English for the sake of reading it. It would be translated into every Language of Europe, and would fix the Opinion of our Unconquerability, more than any Thing could, except driving the Ennemy wholly from the united States.”

Before the close of the year, on December 29, 1780, Massachusetts Representative James Lovell, agreeing with Adams’ request, moved that Congress print 200 copies of the Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, Franco-American treaties, and the state constitutions printed and “bound together in boards”. No doubt, John Adams took pride in the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, which he had drafted earlier in the year.

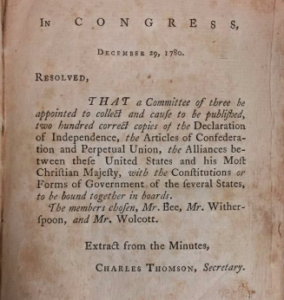

While the Articles of Confederation had been drafted in 1777, it would take several years for the agreement among the states to be formally ratified and take effect on March 1, 1781. Lowell was a signatory to the Articles. His Congressional Resolution requested by Adams is copied below:

Resolved: That a committee of three be appointed to collect, and cause to be published, two hundred correct copies, of the Declaration of independence, the Articles of confederation and perpetual union, the alliance between these United States, and his Most Christian Majesty, with the constitutions or forms of government of the several states, to be bound together in boards.

The members chosen, Mr. [Thomas] Bee, Mr. [John Withserspoon] Witherspoon, and Mr. [Oliver] Wolcott.

The vote by the Continental Congress in December of 1780 preceded the Battle of Yorktown, which occurred almost a year later in October of 1781. The American and French victory over General Cornwallis at Yorktown would precipitate peace negotiations with Great Britain, which would officially end the war with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Francis Bailey first printing in 1781

The Articles of Confederation were ratified in March of 1781. As such, the 200 copies printed by Francis Bailey were the first authorized printing in book form of the Articles, the Declaration of Independence and the assembled state constitutions. Of course, unofficial copies of the contents had been routinely printed in newspapers and pamphlets across the country.

While the title page suggests that it was printed on Market Street in Philadelphia, the first edition of the book was actually published by Bailey in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The British captured Philadelphia in 1777. At various times the itinerant Second Continental Congress fled Philadelphia to meet in Lancaster, York and Baltimore during the war.

The title page pictured below is from a privately held copy, with other scarce copies held by the British Library, the Bibliothèque Nationale of France, the Library of Congress, the American Antiquarian Society, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Rosenbach Museum, Princeton, Yale, Columbia and Harvard University.

Francis Bailey was a member of the Bailey family of printers, who were important in the early history of the United States. Bailey was one of the first American printers to use the Caslon type, which was brought to the colonies from London by Benjamin Franklin in the 1760s. During the War, Bailey served as one of the official printers for the Continental Congress and the State of Pennsylvania.

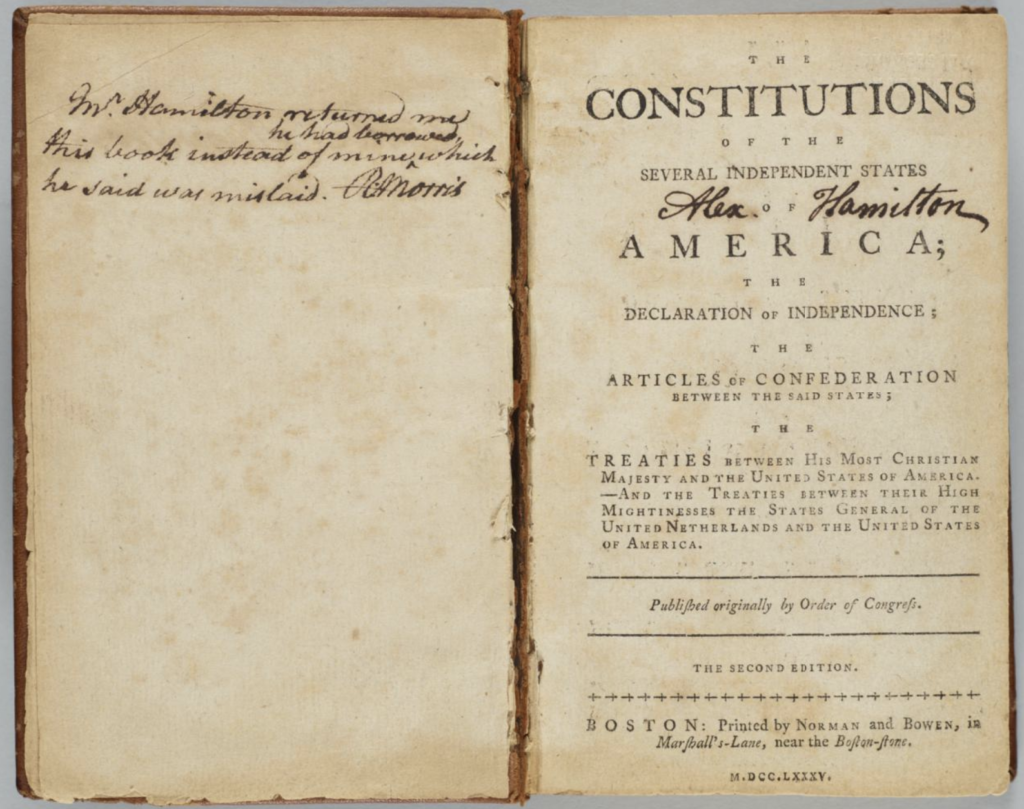

Subsequent editions, depending the printer, contain a map of America at the end of the Revolutionary War. In London, the book was reprinted in 1782 with the title page reflecting “printed for J. Stockdale in Picadilly and sold by J. Walker.” The book was also translated and printed across Europe, beginning with a French edition which preceded the American printing by Bailey.

Click here for a link to a digitized copy of the first edition. Click here for a link to the second American edition printed in Boston in 1785. Alexander Hamilton’s copy, pictured above, is held by Columbia University. Click here for a link to a 1786 re-printing in New York.

Importance of the work and post-script

According to legal historian Kermit Hall, the first American state constitutions written following the Declaration of Independence would later serve as “crucial working models for the framers in Philadelphia” in 1787. As described by historian Willi Paul Adams, “the basic structure of the Federal Constitution of 1787” was modeled after “existing state constitutions writ large.”

In his scholarly work, The First American Constitutions, Professor Adams explains:

The first state constitutions were the most detailed and legally binding collective expression of the revolutionaries’ political ideas in 1776. They differed from pamphlets and newspapers articles on the same subjects in that they institutionalized the American type of republican government as part of the struggle for independence. A decade before the the Federal Constitution, they provided the foundation of legally enforceable rights in the early republic.

The book was also useful in the post war years as new states were carved out of the territory acquired from Britain west of the Appalachian mountains. For example, in 1785 James Madison, the “father of the Constitution” was asked for advice by Kentucky. Madison responded that they should read the “small Volume” printed by Bailey. Click here for Madison’s August 23, 1785 letter to Caleb Wallace.

In his two volume seminal work, The Age of Democratic Revolution, R. R. Palmer examined the “comparative constitutional history of Western civilization” and the conviction that government need not be confined to old norms of “established, privileged, closed, or self-recruiting groups of men.” Between 1776 and 1780, eleven state constitutions were drafted by the former colonies. These constitutions would not only inform the drafting of the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787, but also inspire the French Revolution and the revolutions that followed in Haiti, Poland, the Netherlands and Switzerland. By 1820, more than sixty new constitutions were drafted across Europe. Within another 30 years, approximately 80 constitutions would be drafted and redrafted in Latin America.

Post Script: What about Rhode Island?

When the 1781 first edition was printed, Rhode Island had not yet drafted a constitution of its own. Instead, the 1781 edition included Rhode Island’s original 1663 charter from the 14th year of the reign of King Charles II.

Below the 1663 charter, an explanation was provided that the King had ceded power to the “Governor and company” of Rhode Island as follows:

Since the commencement of hoftiilties by Great Britain, the ftate of Rhode-Island and Providence plantations has not affumed a form of government different from that contained in the foregoing charter. For in that, the king ceded to the governor and company all powers, legiflative, executive, and judicial, referving to himfelf, as an acknowledgment of his fovereignty, a render of the fifth part of the gold and filver ore that fhould be found within the territory.

Click here for a link to the full summary of the operation of government in Rhode Island on page 58 of the first edition. Interestingly, the summary concluded with the observation that “All men profeffing one Supreme Being, are equally protected by the laws, and no particular fect can claim preeminence: From hence it is, that benevolence, hofpitality, and undiffembled honefty remarkably characterife the people.”

James Madison commented on the Rhode Island “encomium” in a letter dated May 5, 1781 to Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson. In his cover letter supplying the first edition, Madison wrote that “[t]he encomium on the inhabitants of Rhode Island was a flourish of a Delegate from [that] State who furnished the Committee with the account of its Constitution, and was very inconsiderably suffered[ed’] to be printed.”

It is noteworthy that the state constitutions were not arrange alphabetically, but rather organized from north to south, starting with New Hampshire. It also bears noting that the state constitutions were printed first, ahead of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the nation’s first treaties with the King of France (identified as “His Most Christian Majesty”).

Four of the colonies adopted their constitutions prior to the Declaration of Independence. In general, states adopted their constitutions in one of three ways: 1) eight states renamed their colonial legislatures as “provincial congresses”; 2) three states elected delegates to a constitutional convention; 3) Connecticut and Rhode Island did not initially adopt new constitutions.

New Hampshire is not only the first state listed in the book, it was also the first state to adopt its constitution on January 5, 1776. Vermont was not formally recognized as a state until later, due to a boundary dispute with it neighbors. Nevertheless, Vermont delegates met in convention in 1777 to adopt their constitution (which was the first to prohibit slavery).

Massachusetts was the last of the states original states listed in the book to adopt a constitution. Its 1778 draft constitution was voted down in town meetings. Upon his return from Europe during the Revolutionary War, John Adams was the principal drafter of the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, which was ratified by a 2/3 vote. Despite its “late” adoption, the Massachusetts Constitution is the world’s oldest written constitution still in operation today.

Additional reading:

The Age of Democratic Revolution A Political History of Europe and America, 1760 – 1800, R. R. Palmer (1959)