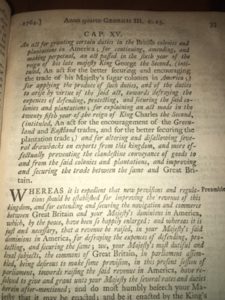

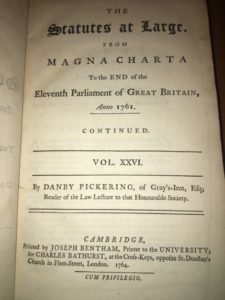

The SUGAR ACT OF 1764, Chapter XV, Volume XXVI of Danby Pickering’s Statutes at Large, printed by Joseph Bentham in 1764 (4 Geo III to 5 Geo III)

[4 Geo 3 c. 15]

The Sugar Act (also known as the American Revenue Act of 1764 or the American Duties Act) was the first act of Parliament passed specifically to raise money in the American colonies. The Act revised the existing system of custom regulations, established new taxes on imports into the colonies, and established vice admiralty courts in Halifax, Nova Scotia, aimed at curtailing widespread smuggling of molasses/sugar between the British colonies and the French Indies.

The Sugar Act (also known as the American Revenue Act of 1764 or the American Duties Act) was the first act of Parliament passed specifically to raise money in the American colonies. The Act revised the existing system of custom regulations, established new taxes on imports into the colonies, and established vice admiralty courts in Halifax, Nova Scotia, aimed at curtailing widespread smuggling of molasses/sugar between the British colonies and the French Indies.

The Sugar Act reduced the rate of tax on molasses from six pence to three pence per gallon, which Prime Minister Grenville expected would offset by stricter enforcement. The Act also taxed more goods, including sugar, certain wines, coffee, pimiento, cambric and formerly duty-free Madeira wind from Portugal.

Following the French & Indian War (also known as the Seven Years War) the British were saddled with substantial public debt. George Grenville was appointed Prime Minister in 1763 and was desperate for new sources of revenue. Unlike his brother-in-law, William Pitt, Grenville agreed with the prevailing opinion in Britain that the colonies had been indulged too long and should start paying the cost of defending the British empire.

Grenville believed that the lower duties on molasses would convince the colonists to pay the tax and reduce smuggling. The Act allowed seizure from smugglers and the vice-admiralty courts did not permit jury trials. Equally problematic, the defendants were required to prove their innocence in the vice admiralty courts, which otherwise contradicted British law.

Under Grenville’s enforcement policies, ship captains were obligated to list all of the goods they carried aboard their ship. The ship manifests were required to be approved before ships could leave colonial ports. The British navy also began to stop and search ships for smuggled cargo. Taken together, these steps made it difficult to avoid paying duties. If an accused smuggler was apprehended, the vice admiralty courts lacked juries and treated the accused as guilty until proven innocent.

Little did Grenville realize that he was antagonizing the colonists, who believed that the Sugar Act and its anti-smuggling provisions violated their rights as Englishmen.

The Sugar Act was followed in 1765 by the more notorious Stamp Act.

Background:

The English policy of “Salutary Neglect” that was in effect dating back to the 1600s looked the other way when the colonists violated the law by smuggling/bribing customs officials. Under the prevailing mercantilist theory contained in the Navigation Acts, the colonies were only permitted to directly trade with England. After more than a hundred years of lenient enforcement, the colonies bristled when England began stricter enforcement to generate income to pay for the cost of the French and Indian War.

The Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765 provoked fierce colonial resistance. Many colonial leaders had grown accustomed to being independent under the British policy of salutary neglect. In 1764, James Otis, a firebrand lawyer and pamphleteer, wrote that “taxation without representation is tyranny.” In a Boston town meeting in May of 1764, Samuel Adams agreed with Otis and helped found Committees of Correspondence which enabled the colonies to share information about the new British laws and strategies for challenging them.

James Otis is pictured above. He challenged writs of assistance which allowed the British authorities to enter any home without advance notice or probable cause. In describing James Otis, Sam Adams explained that, “I have been young and now I am old, and I solemnly say I have never known a man whose love of country was more ardent or sincere, never one who suffered so much, never one whose service for any 10 years of his life were so important and essential to the cause of his country as those of Mr. Otis from 1760 to 1770.”