U.S. Constitution (May 25 to September 17, 1787)

Historians widely agree that James Madison is the “father of the Constitution.” He is properly credited as a primary drafter of the U.S. Constitution and a leading organizer and scholar of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He was first to arrive in Philadelphia having systematically prepared by studying over 200 books on government and history. A month before the Convention he summarized the results of his research on past republics and confederations in his essay Vices of the Political System of the United States, which identified eleven major flaws with the Articles of Confederation and his proposed solution. Click here for Madison’s text and commentary.

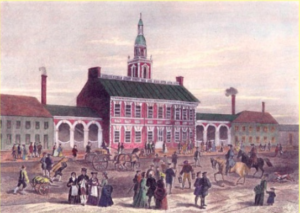

Madison played a critical role as the head of the Virginia delegation. As the author of the “Virginia Plan” Madison framed the agenda for the founders. Madison’s detailed notes on the debates at the Constitutional Convention provide one of the most instructive primary sources of the summer proceedings in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. The Federalist papers co-written with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay were indispensable for the ratification process. After the Constitution was ratified, Madison was the driving force behind the Bill of Rights which he introduced and shepherded through the first Congress.

John Adams described the Constitutional Convention as “the greatest single effort of national deliberation that the world has ever seen.” Nevertheless, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, who played critical roles in drafting the Declaration of Independence, were only able participate from a distance when the Constitution was drafted. Both Adams and Jefferson were serving as the American ambassadors to England and France in 1787. Thus, the drafting of the Constitution fell to others founders, including James Madison (the “Father of the Constitution” and drafter of the “Virginia Plan”), Edmund Randolph (who presented the “large state/Virginia Plan” and prepared the first draft with the Committee on Detail), William Paterson (who proposed the “small state /New Jersey Plan”), Roger Sherman (combined equal representation in the Senate with proportional representation in the House, known as the “Connecticut Compromise/Great Compromise”), John Rutledge (Chair of the Committee on Detail), James Wilson (who revised Randolph’s draft in the Committee on Detail), and Gouverneur Morris (known as the “Penman of the Constitution” who finalized and consolidated the Constitution), among others.

As described by historian Joseph Ellis, the founding generation established the first nation-sized republic. “Until then it was presumed that republican governments based on the principle of popular consent could function only in small areas like Greek city-states or Swiss cantons, because of the inherent weakness of republican government made it incapable of decisiveness or the management of far-flung population.” Click here for a link to Ellis’ book, American Creation (2007).

Ellis also credits the founders with rejecting the conventional wisdom universally accepted since the days of Aristotle that popular sovereignty was by definition singular and needed to be centralized and indivisible. “The Constitution defied this assumption by creating multiple and overlapping sources of authority in which the blurring of jurisdiction between federal and state power became an asset rather than a liability.”

According to Ellis, the United States grew out of not one, but conflicting founding impulses. The first founding event occurred in 1776, “which declared American independence and the second in 1787-1788, which declared American nationhood.” Of course, the Declaration of Independence was the seminal event in 1776, whereas the Constitution was the second act, a generation later. While the Declaration was a “radical” document that recognized national rights and sovereignty in the individual, the Constitution was a “conservative” document that located sovereignty in the collective “we the people.” To the Declaration, government was the evil resisted by the people based on the notion that rebellion was a natural act. For the Constitution, government is the “essential protector of liberty rather than its enemy, and values social balance over personal liberation.” According to Ellis, “it is extremely rare for the same political elite to straddle both occasions…for the same men who make a revolution also to secure it.”

Historian Catherine Drinker Bowen emphasizes the spirit of compromise that animated the Constitutional Convention:

Compromise can be an ugly word, signifying a pact with the devil, a chipping off of the best to suit the worst. Yet in the Constitutional Convention the spirt of compromise reigned in grace and glory; as Washington presided, it sat on his shoulder like the dove. Men rise to speak and one sees them struggle with the bias of birthright, locality, statehood, South against North, East against West, merchant against planter. One sees them change their minds, fight against pride, and when the moment comes, admit their error. Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention, May to September, 1787 (Catherine Drinker Bowen, 1986)

This observation is consistent with the wisdom of 81 year old Benjamin Franklin, who closed out the Constitutional Convention with these words:

I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them: For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others. . . In these sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults, if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us, and there is no form of Government but what may be a blessing to the people if well administered, and believe farther that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years. . . I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution. For when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men, all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected? It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies, who are waiting with confidence to hear that our councils are confounded like those of the Builders of Babel; and that our States are on the point of separation, only to meet hereafter for the purpose of cutting one another’s throats. Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best.

Click here for the full text of Franklin’s September 17, 1787 speech.

When was the “United States” created? When did the former colonies consider themselves to be a “nation”? According to first words in the title of the Declaration of Independence, the document was the result of a “unanimous Declaration of thirteen united States of America.” Similarly, in the body of the Declaration, the colonies declared themselves “Free and Independent States.”

While it is clear that the colonies were asserting their independence from Britain on July 4, 1776, the colonies were not yet a single unified nation. It would take over a decade before a collective national identity would be forged, leading to the ratification of the Constitution in 1789. For this reason, many historians consider the adoption of American’s Constitution as the second American Revolution. “Constitution Day” (also known as “Citizenship Day”) is celebrated on September 17, the date that the Constitution was signed in Philadelphia in 1787, when a free and independent “nation” was ready to finally emerge.

“The government they created in 1781 [under the Articles of Confederation] was not really much of a government at all and was never intended to be. It was, instead, what one historian has called a ‘Peace Pact’ among sovereign states that regarded themselves as mini-nations of their own, that came together voluntarily for mutual security in a domestic version of a League of Nations.” Click here for a link to Ellis’ The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789. As explained by Ellis, the colonies were held together prior to 1776 by their membership in the British empire. The only thing holding them together after 1776 was their common goal of leaving the British empire.

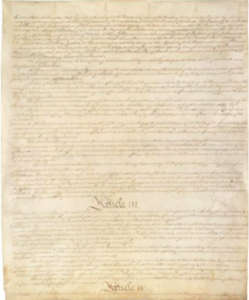

Thus, it would take more than a decade for the newly independent colonies to recognize that they needed to form a unified country. The gradual realization that the Articles of Confederation was a failure was necessary for this nationalizing process to result in a “more perfect union.” In fact, the term “union” is used six times in the Constitution, including Article IV which provides that “The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.” Of course, the President’s annual State of the Union address retains this nomenclature.

At the Constitutional Convention, Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania was assigned the final task of editing the twenty-three articles of the draft Constitution. Morris took the “Committee on Detail” draft and compressed it into the seven Articles that remain in place today. According to Madison, “the finish given to the style and arrangement of the Constitution fairly belongs to the pen of Mr. Morris.”

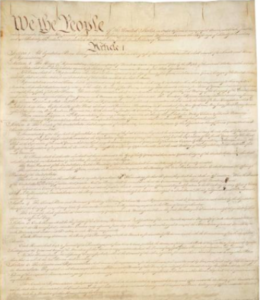

In doing so Morris (who is pictured below) also revised the preamble in what Ellis describes as “probably the most consequential editorial act in American history.” The Committee draft of the preamble to the Constitution originally provided that “We the people of the states of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia, do ordain, declare and establish the following constitution…” Morris single handedly elected to replace this unwieldy list with the phrase “We the People of the United States.” Independence for the new nation was now complete.

Patrick Henry, the outspoken Anti-Federalist, challenged the phrase “We The People” during heated debates with James Madison at the Virginia ratification convention. Henry inquired, “Who authorized them to speak the language of ‘We the People,’ instead of ‘We the States’?” Madison replied that government should be established “by the people at large.” According to Madison, “In this particular respect the distinction between the existing and the proposed governments is very material. The existing system has been derived from the dependent derivative authority of the legislatures of the states; whereas, this is derived from the superior power of the people.”

In giving credit to Morris as the “penman” of the Constitution, Madison admitted that Morris could not have made a “better choice.” Thus, the concept of independence for the “united States of American” begins with Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence. In crafting the Constitution a generation later, in the same room in Philadelphia, Madison and Morris recognized that a new independent nation was being formed, by “We the People of the United States.” Ellis reasons that it was not by accident that the same location was selected for the Constitutional Convention that gave birth to the Declaration of Independence. “By choosing the same city, the same building, even the same room where those values were first discovered and declared, the delegates were making a statement – whether they knew it or not – that whatever they produced should be regarded as a continuation rather than a rejection of the ‘the spirit of ’76.’ ”

Critical dates leading to the Constitutional Convention: The colonies declared their independence from Britain in July of 1776. Independence was declared on July 2; the text of the Declaration of Independence was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4; the Declaration was finally signed on August 2.

The country’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, was adopted by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777. The Articles were eventually ratified on March 1, 1781. Recognizing systemic defects with the Articles, on February 21, 1787, the Confederation Congress (also known as the “Congress of the Confederation”) called for a Constitutional Convention to amend the Articles of Confederation. Because “plan A” was increasingly recognized as a failure, it was unclear what the future of the Revolution would hold if “plan B” did not succeed.

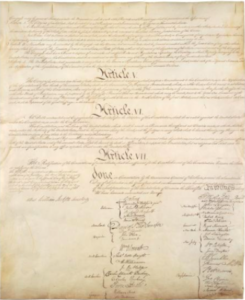

The Constitution was drafted in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787. On September 17, 1787 a majority of the delegates signed the final draft of the Constitution, but the Constitution required ratification by nine states to take effect. On December 7, 1787, Delaware became the first state to ratify. Ten months later, New Hampshire became the all important ninth state to ratify on July 21, 1788. The nine state threshold was only possible, however, after a compromise was reached in February of 1788 when Massachusetts and other holdout states agreed to ratify with the assurance that a Bill of Rights would be adopted.

Although Madison is widely regarded as the “father of the Constitution,” he humbly explained that credit properly belonged to “many heads and many hands.” In a letter to William Cogswell in March of 1834 (at the age of 84) Madison modestly wrote that:

You give me a credit to which I have no claim in calling me “the writer of the Constitution of the United States.” This was not, like the fabled Goddess of Wisdom, the offspring of a single brain. It ought to be regarded as the work of many heads and many hands.

Additional reading and primary sources:

Journals of the Continental Congress (Library of Congress)

Constitution (National Archives)

U.S. Constitution and Primary Documents (Library of Congress)

Articles of Confederation and related primary sources (Library of Congress)

Center for the Study of the American Constitution

The Quartet, Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789 (Ellis, 2015)

Farrand’s Records of the Federal Convention of 1787

Annotated Constitution (Library of Congress)

The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution (David Stewart, 2007)