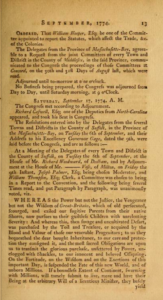

Suffolk Resolves (September 9, 1774)

In retaliation for the Boston Tea Party in 1773, Parliament passed the punitive Coercive Acts in 1774. By shutting down the Port of Boston, deploying troops in and around Boston, and revoking Massachusetts’ charter, Parliament wrongly believed that it would isolate and make an example of Boston, deterring further colonial resistance. Yet, the harsh British laws (labeled the “Intolerable Acts” by the colonists) only solidified colonial unity. Rallying to the defense of Boston, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774. The Continental Congress unanimously endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, to the applause of the chamber, one day after they were delivered to Philadelphia by Paul Revere from Suffolk County.

The Massachusetts Government Act prohibited unauthorized town, district, or precinct meetings, but did not mention “county” meetings. So the defiant Massachusetts colonists held County Congresses in rural locations. Doing so not only circumvented British restrictions on “town” meetings but also allowed Boston to make common cause with rural communities. Delegates from nineteen Suffolk County towns meet on September 9, 1774 in Milton, Massachusetts, and unanimously passed the Suffolks Resolves (which consisted of 19 resolutions that taken together formed a coherent public relations campaign and plan for resisting the British). The Resolves were drafted by Dr. Joseph Warren (pictured below by John Singleton Copley), a leader of the Sons of Liberty, who was later killed in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

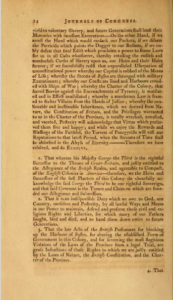

While the Resolves began with a pro forma declaration of loyalty to King George, the Suffolk Resolves made clear that “no obedience is due” to unlawful Parliamentary laws which were “gross infractions” of the “Laws of Nature, the British Constitution, and the Charter of Province.” It mattered not to colonial leaders that Parliament had just annulled the Charter of Massachusetts Bay since doing so violated both natural rights and the rights of the colonists under the British law. Similar reasoning and references to natural law would be used by Thomas Jefferson when he drafted the Declaration of Independence two years later.

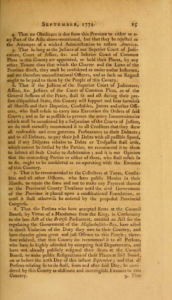

In other words, rather than being cowed by the repressive Coercive Acts of 1774, Massachusetts counties responded by signaling to Parliament that colonial resistance would not only continue but intensify. The Suffolks Resolves effectively declared the Intolerable Acts unconstitutional and thus void. The Resolves called on the people of Massachusetts (and all 13 colonies) to form new governmental institutions funded by the taxes that would otherwise be paid to British authorities. The most provocative resolution called for the arming of local militias, doing their utmost to aquaint themselves with the “Art of War” and defiance of British military authority, if necessary.

As soon as the Suffolk Resolves were approved, they were delivered in five days time by Paul Revere to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Similar resolves and statements of colonial resistance were also adopted across Massachusetts, but the powerfully written Suffolk Resolves had the added influence of representing the views of Boston, which is located in Suffolk County. On September 17, 1774, the Continental Congress unanimously endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, one day after they were delivered by Paul Revere to Philadelphia. John Adams’ diary on the day that the Suffolk Resolves were approved by the Continental Congress described the event as follows:

“This was one of the happiest Days of my Life. In Congress We had generous, noble Sentiments, and manly Eloquence. This Day convinced me that America will support the Massachusetts or perish with her.” Click here for John Adams’ diary entry for September 17, 1774.

As intended by Dr. Warren and Paul Revere (who is pictured below in a portrait by John Singleton Copely), the Suffolk Resolves sent a defiant but unifying message to both Parliament and American leaders in the First Continental Congress. Among other things the Suffolk Resolves affirmed that there was popular support for military resistance, if necessary, through the raising of militia across Massachusetts. The Resolves further expressed an intent to defend colonial rights through the use of “all lawful ways and means in our power to maintain, defend and preserve those civil and religious rights and liberties.”

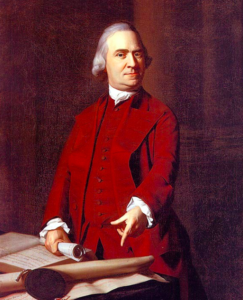

Fifty-six delegates from 12 colonies attended the First Constitutional Congress, including cousins Sam and John Adams (from Massachusetts), Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and George Washington (Virginia), John Jay (New York), brothers John and Edward Rutledge (South Carolina), and Roger Sherman (Connecticut). After describing the “spirited and patriotic Resolves from your County of Suffolk” that were delivered by Mr. Revere, Sam Adams indicated that he expected that “America will make a point of supporting Boston to the utmost.” Click here for Sam Adams’ letter of September 19, 1774 to Charles Chauncy.

While Sam Adams was encouraged by the support Boston was receiving, he knew that there were limits on how far and fast moderates could be pushed. In correspondence to Dr. Warren, Adams opined that the “all-American cause so much depends on each colony’s acting agreeably to the sentiments of the whole.” Adams acknowledged that heretofore they had been “accounted by many” as being “intemperate and rash,” but were now being “universally applauded as cool and judicious, as well as spirited and brave.” Click here for a link to Sam Adams’ letter of September 25, 174 to Dr. Joseph Warren.

Recognizing the pace of the revolution should not get ahead of popular opinion, Adams warned Warren that the key was to “act merely on the defensive, so long as such conduct may be justified by reason and principles of self preservation, but no longer.” In other words, “patience and fortitude,” “perseverance in a firm and temperate conduct” was necessary to hold the colonies together. Doing so required tamping down on rumors that Boston was aiming for “total independency.”

Similarly, when George Washington heard that the “fixed aim” of the Sons of Liberty in Massachusetts was “total independency,” he questioned the representatives from Boston whether this was accurate. John Adams and Samuel Adams misled Washington, denying that this was true. According to Washington’s account of his discussions with the Boston leaders:

I am well satisfyed, as I can be of my existence, that no such thing is desired by any thinking man in all North America; on the contrary, that it is the ardent wish of the warmest advocates for liberty, that peace & tranquility, upon Constitutional grounds, may be restored, & the horrors of civil discord prevented. Click here for a Washington’s letter to Robert McKenzie dated October 9, 1774.

Although Sam and his cousin John Adams knew full well that Boston radicals had considered attacking British garrisons and otherwise provoking independence, they also knew that the Continental Congress would not its support overt military activity. Thus, the Boston leadership emphasized to the Sons of Liberty back home the need to slow down the revolution. Samuel Adams wrote to James Warren (James Warren succeeded Dr. Joseph Warren as President of the Massachusetts Provisional Congress after Dr. Warren was killed at Bunker Hill):

I beseech you to implore every Friend in Boston by every thing dear and sacred to Men of Sense and Virtue to avoid Blood and Tumult. They will have time enough to dye. Let them give the other Provinces opportunity to think and resolve. Rash Spirits that would by their Impetuosity involve us in unsurmountable Difficulties will be left to perish by themselves despisd by their Enemies, and almost detested by their Friends. Nothing can ruin us but our Violence.

In an effort to avoid alienating moderates, Resolve number 18 heartily warned all persons in the community “not to engage in any routs, riots, or licentious attacks.” Subversive activity was not sanctioned, but “a steady, manly, uniform, and persevering opposition” was encouraged. In the inspired words of Dr. Warren, colonial opposition would “convince our enemies that in a contest so important, in a cause to solemn, our conduct shall be such as to merit the approbation of the wise, and the admiration of the brave and free of every age and every country.” Who could disagree with that? Other Resolves provided for the boycotting British goods, encouraged self reliance and local manufactures, and recommended the stockpiling of military supplies. Click here for the full text of the Suffolk Resolves.

After the Continental Congress approved the Suffolk Resolves, British administrative control began to unravel across the colonies. Increasingly unified colonial resistance and newly emerging shadow governments diverted tax revenue from royal authorities. Independent local Committees of Correspondence and/or Committees of Safety began assuming control over local governmental functions. Local leaders also began assembling and organizing local militias. By the end of 1774, John Murray, the Royal Governor of Virginia, stated in a report to London that companies of militia were forming throughout the colony to protect the Committee and that he no longer controlled the colonial government. Spies, Patriots and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War (Kenneth Daigler, 2014)

As recognized by Historian Walter Isaacson, “it is hard to pinpoint precisely when America cross the threshold of deciding that complete independence from Britain was necessary an desirable.” Click here for Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (Walter Isaacson, 2003). Nevertheless, it is clear that the Suffolk Resolves was an important milestone on the path to colonial independence. It is also clear that Dr. Joseph Warren played a critical leadership role in this process. As summarized by historian Ethan Rafuse, “No man, with the possible exception of Samuel Adams, did so much to bring about the rise of a movement powerful enough to lead the people of Massachusetts to revolution.”

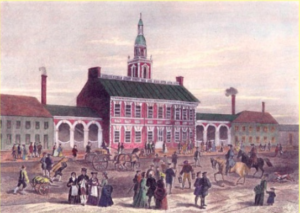

The Suffolk Resolves “House” in Milton Massachusetts is pictured below. The House today serves as the headquarters for the Milton Historical Society.

Journals of the First Continental Congress

The American Revolution (Joseph C. Morton, 2003)

The Writings of Samuel Adams, Vol. III (Harry Cushing, 1907)

Samuel Adams, Father of the American Revolution (Mark Puls, 2006)

The Life and Times of Joseph Warren (Richard Frothingham, 1865)

The Long Road to Change: America’s Revolution 1750-1820 (Eric Nellis)

When Rabble-Rousing Samuel Adams Slowed Down the Revolution (Journal of the American Revolution)

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (Walter Isaacson, 2003)