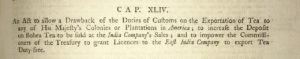

The Tea Act of 1773

“Taxation without representation” is commonly understood as one of the causes of the Revolutionary War. Yet, one of the little know ironies of American history is that the Tea Act of 1773, which precipitated the Boston Tea Party, was not a new tax on tea. In fact, Parliament did not anticipate that the Tea Act would be controversial since it actually lowered the cost of tea. Thus, the simmering grievances between the colonies and England weren’t simply a dispute about taxes on tea, but a larger underlying dispute over self-government, arbitrary British rule, resistance to a tea monopoly, and ham fisted British policy.

Rather than creating a new tax on tea, the Tea Act of 1773 involved the extension of a tea monopoly to the colonies. At the time, Britain’s East India Tea Company (hereinafter the “East India Tea Company” or the “Company”) held an official monopoly on the tea trade with the Far East. Despite its monopoly, the Company was on the verge of bankruptcy. It owed money to the British government and was holding a large quantity of unsold tea that was rotting in warehouses in England. The Company’s financial difficulties were the result of prior boycotts by the colonies, the smuggling of less expensive Dutch tea, and an economic downturn following the French and Indian War.

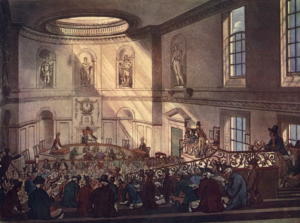

Pictured below is the East India Tea Company’s headquarters in London, a watercolor by Thomas Malton circa 1800.

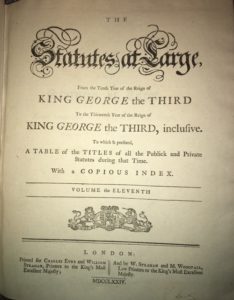

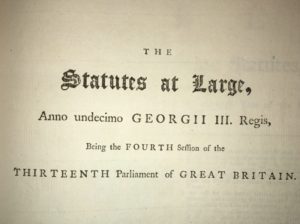

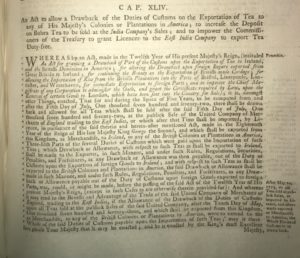

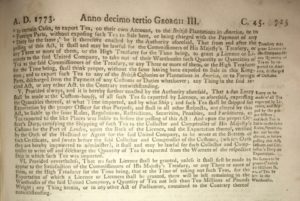

Parliament passed the Tea Act of 1773 in an effort to assist the struggling East India Tea Company. Prior to passage of the Act, the Company was only permitted to exercise its exclusive monopoly by selling its tea at auction in London. The Tea Act removed this restriction and extended the Company’s right to export tea directly to the colonies, without having to sell through wholesalers. The Act also eliminated taxes on tea entering Britain.

Pictured below is the auction room of the East India Company, circa 1809.

By enabling the Company to export directly to the colonies, rather than through colonial intermediaries, colonial middlemen would be cut out of the tea business. The Tea Act thereby simplified the sale of tea for the East India Tea Company, making the tea business more profitable for the struggling monopoly. The new price of tea would now be lower than the cost of smuggled tea. The Tea Act would thus strengthen the East India Tea Company’s monopoly and undercut colonial competition. Since the existing tax on tea would now be collected in the colonies rather than in London, the revenue stream could be used by royally appointed governors without approval by colonial legislatures.

Over the preceding decade the colonists had resisted direct taxes imposed by Parliament. Starting with the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767, the colonists challenged the constitutionality of direct taxes and resented corrupt royal officials. In passing the Tea Act, Parliament expected the colonists to surrender their principles in exchange for lower cost tea. Would economic self-interest for consumers and lower prices overcome colonial resistance to buying taxed tea? Within months of passage of the Tea Act, the answer became clear. The Act quickly became the spark that rekindled colonial opposition to Britain, even though the Act was not a new tax.

The Tea Act proved to be incendiary for a host of reasons: 1) The Act inflamed influential and vocal colonial tea merchants and smugglers who stood to lose economically. Under the Act colonial tea sellers would be at a grave competitive disadvantage compared to the the expanded East India Tea Company monopoly. The Act impacted both legitimate tea importers who were not granted licenses by the East India Tea monopoly along with smugglers of Dutch tea. If the East India Tea Company could control the colonial tea market, its long term health would be assured. Other prominent merchants also worried that similar “tea acts” for other products could follow.

2) The Tea Act revived concerns over taxation without representation, which had been festering since the Stamp Act of 1765. The Stamp Act had been the first direct, internal tax imposed on the colonies. The Stamp Act was met with intense resistance and boycotts. The next year, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766. By passing the Declaratory Act of 1766, Parliament made clear that it retained the right to impose direct taxes. The colonists argued that only locally elected colonial assemblies could enact direct taxes.

3) Colonial leaders perceived the Tea Act as a Trojan horse intended to lull the colonies into accepting Parliament’s right to impose direct taxes. If so, the Act was an insidious and unconstitutional tax. Under this view, the “seductive” Tea Act was a tactic designed to overcome colonial resistance with the carrot of lower taxes.

4) The Tea Act would empower colonial governors with an independent source of revenue, outside the control of colonial legislatures. Rather than relying on appropriations by Parliament, the Tea tax would now be collected at the colonial ports of entry and paid directly to the royally appointed officials.

5) The agents commissioned by the East India Tea Company to sell tea and collect taxes were perceived as corrupt. For example, in Boston seven merchants who were loyal to the king were hand-picked as consignees/agents to sell the East India Company’s tea. Two of the consignees were the sons of Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Boston Tea Party

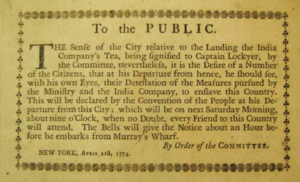

When the Tea Act was passed on May 10, 1773, seventeen million pounds of unsold surplus tea was stored in London warehouses. The East India Tea Company released tea shipments for the colonial ports of Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Charleston. When the colonies learned of the Tea Act, the Sons of Liberty and colonial committees of correspondence began mobilizing public opinion to resist, as they had years earlier against the Stamp Act. Protestors pressured the local agents (consignees) of the East India Tea Company to resign their commissions.

Colonists in New York and Philadelphia refused to allow the unloading of the tea and sent the ships back to London. While tea was unloaded in Charleston, local leaders insisted that it be secured in warehouses at the port. Charleston’s tea remained locked in storage until it was sold during the Revolutionary War to fund the war effort.

On November 28, 1773, the first of three ships, the Dartmouth, arrived in Boston. Sam Adams organized a mass town meeting for the Old South Meeting House on November 29. The crowd was so large that attendees couldn’t all fit in Faneuil Hall. The citizens of Boston voted to prevent any ships from being unloaded and to prevent the payment of the tea tax.

Boston’s Royal Governor, Thomas Hutchinson, refused to be intimidated. Under the rules, ships were required to be unloaded within twenty days. For nineteen days a standoff ensued. Two more ships, the Eleanor and the Beaver, arrived on December 3rd and 15th. Armed sentries were organized to watch the ships to prevent unloading of tea. Messengers were kept on standby, with horses saddled at the ready to alert the community if an attempt was made to unload the ships. Additional sentinels were stationed in church-belfries to sound an alarm.

On December 16, 1773, the 20th day, Sam Adams and John Hancock convened another town meeting. It is believed that approximately five thousand Bostonians, out of a population of 16,000 Boston residents, attended. News arrived that Governor Hutchinson would not compromise. If the three ships attempted to depart without paying the tea tax, the cannons of Castle William and British warships in the harbor were under orders to sink them. Sam Adams announced that, “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country!”

Many believe that Sam Adam’s statement was a signal. Approximately 50 members of the Sons of Liberty, dressed as Mohawk Indians, took matters into their own hands. With thousands watching along Griffin’s Wharf, 45 tons of tea 340 chests were thrown into Boston harbor. No injuries were reported during the protest. Other than the tea and chests, no property was damaged or looted during the Boston Tea Party. Reportedly, the participants even swept the ships’ decks before they left.

American historian Arthur Schlesinger in his 1918 book The Colonial Merchants and the American Revolution, 1763-1776 acknowledges that the success of the Boston Tea party is owed, among others, to “the infinite craft and resourcefulness of the deus ex machine, Sam Adams.” Assisting Adams and “his effort to foster continuous discontent” was the fact that “merchants as a class joined in the popular demand for the resignation of the consignees and against the landing of the tea.” Schlesinger also recognizes the important role played by Boston Gazette publisher and agitator Benjamin Edes.

For Schlesinger, the colonial merchants in the port cities were driven more by profits and self interest than by politics. It should also be noted that Sam Adams and John Hancock were notorious smugglers. Nevertheless, even if colonial leaders and the Sons of Liberty had mixed objectives and competing interests, it mattered not. Britain retaliated by passing the Coercive Acts to punish Boston. The rest is history.

According to Philadelphia merchant Thomas Warton, “it is impossible always to form a true judgment from what real motives an opposition springs.” Click here for a link to Warton’s letter and other primary sources in Tea Leaves: Being a Collection of Letter and Documents relating to the Shipment of Tea to the American Colonies in the Year 1773 by the East India Tea Company (Crane, 1884).

Click here for the text of the Tea Act.

Click here for a discussion of the Boston Port Act, the first of the Coercive Acts passed by Parliament in 1774 in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party.

Additional reading:

The Long Fuse: How England Lost the American Colonies, 1760-1785 (Don Cook, 1995)

Reluctant Break with Britain from Stamp act to Bunker Hill (Gregory Edgar, 1997)

All About Tea (William Ukers, 1935)

Samuel Adams: Father of the American Revolution (Mark Puls, 2006)

John Hancock: Merchant King and American Patriot (Harlow Unger, 2005)

The Economy of British America: 1607-1789 (McCusker & Menard, 1991)

Retrospect of the Boston Tea-Party, with a Memoir of George R. T. Hewes (James Hawkes, 1834)