Carriage Act of 1794 (Hamilton and the Supreme Court)

[Third Congress, Session I, Chapter 45; 1 Stat. 373-375]

After Alexander Hamilton stepped down from Washington’s cabinet in January of 1795, he returned to the practice of law. As described by historian Ron Chernow, “By common consent, he [Alexander Hamilton] was New York’s premier lawyer, with an elite clientele that included the city of Albany and the state of New York.” Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (2004). According to Judge James Kent, “Hamilton was employed in every important and every commercial case.”

In early 1796, Hamilton was called upon by Attorney General William Bradford to represent the federal government before the Supreme Court in an important case addressing the constitutionality of a tax that Hamilton had proposed as Secretary of Treasury. In the case of Hylton v. United States, 3 U.S. 171 (1796), Hamilton successfully defended his handiwork in the first case testing the constitutionality of an act of Congress. The Court unanimously agreed with Hamilton that the Carriage Act was constitutional because the carriage tax was a permissible excise tax, rather than a direct tax that needed to be apportioned among the states.

Professor Chernow summarizes the Supreme Court decision in the Hylton case as follows:

[The Supreme Court] approved Hamilton’s argument that this excise tax was legal and that Congress had power “over every species of taxable property, except exports.” The decision in Hylton v. United States not only endorsed Hamilton’s broad view of federal taxing power but represented the first time the Supreme Court ever ruled on the constitutionality of an act of Congress.

According to at least one newspaper, “the whole of [Hamilton’s] argument was clear, impressive and classical.” Justice James Iredell described Hamilton’s oral argument in glowing terms:

“Mr. Hamilton spoke in our Court, attended by the most crowded audience I ever saw there, both Houses of Congress being almost deserted on the occasion. Though he was in very ill health, he spoke with astonishing ability, and in a most pleasing manner, and was listened to with the profoundest attention. His speech lasted about three hours.”

Hamilton’s legal defense in the Hylton case and his broad interpretation of Congress’ taxing powers under Article I of the Constitution would later be cited by Chief Justice Roberts in his 5-4 decision upholding the Affordable Care Act’s health insurance mandate in 2012. Click here for a link to Roberts’ opinion in N.F.I.B. v. Sebeleus, 567 U.S. 519 (2012). The Hylton case preceded Chief Justice Marshall’s seminal decision in Marbury v. Madison (1803) by seven years, but raised the identical issue: whether the courts were vested with the power to declare legislation unconstitutional (i.e., judicial review). Pictured below is a statute of Hamilton in New York’s Central Park, located behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pictured below is an oil on canvas depiction of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall and old City Hall by Ferdinand Richard from 1858. For a decade the Supreme Court met in Philadelphia’s Old City Hall, until the Court moved to the new Capital in Washington, D.C.

Background: The Carriage Act (also known as the Carriage Tax Law) was one of several taxes adopted by Congress in the spring of 1794 to raise revenue in the face of growing tensions with England. The U.S. was simultaneously engaged in hostilities with Native Americans in the Northwest Territory, who were being agitated by British agents in the frontier. Ultimately, war with England would be averted by the controversial Jay’s Treaty of 1795, which was largely orchestrated by Alexander Hamilton. While Jay’s Treaty was opposed by Jefferson and Madison, it delayed conflict with England until the War of 1812 and secured the removal of British troops from northern forts and the Great Lakes.

During the last week of March 1794, the House set up a Committee on Ways and Means to offer plans for raising needed revenue. Two days before John Jay’s confirmation as special envoy to Great Britain, the Committee submitted its report on April 17, 1794. The Committee borrowed from proposals prepared by Hamilton in 1792 and suggested the following sources of revenue: a carriage tax (in modern terms think of a tax on luxury cars), increased customs duties on specified articles, additional tonnage duties, a stamp tax (which was ironic given the consequences of the British Stamp Act of 1765), increased excise taxes on sales at action, excise taxes on tobacco, snuff and sugar, and a license fee for the sale of foreign distilled liquors and wines. Pictured below is George Washington coach house (garage) at Mount Vernon and a horse drawn carriage believed to have been made by the same coach maker who built Washington’s carriage. Click here for a link to Mount Vernon’s online tour.

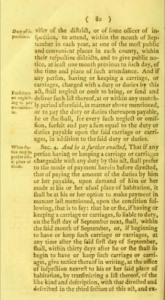

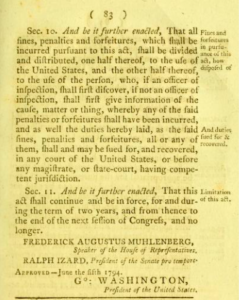

The Act was adopted on June 5, 1794, near the end of the legislative session. As a luxury tax, the Carriage Act applied only to personal use carriages and excluded commercial and agricultural wagons, carts and drays. The Carriage tax rates were graded from a maximum rate of $10 on a coach, $8 on a chariot, down to $6 on any other four wheeled carriage and $2 on a chaise or other two wheeled vehicle. The Act provided for a penalty for nonpayment equal to the amount of the tax. Suits for recovery could be brought “in any court of the United States, or before any magistrate, or state court, having competent jurisdiction.” The law provided that it would sunset after three years in 1797. Pictured below is an example of a two wheeled chaise. President Washington maintained an assortment of fashionable carriages but none of the originals have survived.

The use of carriage taxes was not new and had been used by several states for years. As early as 1787, when Hamilton was a member of the New York Assembly, had proposed similar tax. An Act for Raising Certain Yearly Taxes Within This State, February 9, 1787. In his Report on the Redemption of the Public Debt Hamilton had proposed a federal carriage tax in November of 1792.

The House report separately proposed additional taxes of $750,000 to “be raised by direct tax, for the year 1794, to be apportioned among the States, agreeably to the rule prescribed by the Constitution.” Importantly, the House report distinguished between “direct” taxes and other “indirect” or excise taxes and characterized the carriage tax as an indirect tax. Prior to the adoption of the 16th Amendment this subtle distinction was important because Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution contains the following prohibition: “No capitation, or other direct tax, shall be laid, unless in proportion to the census or enumeration heron before directed to be taken.”

Yet, the Constitution does not contain a definition of the term “direct” tax. The question was particularly complicated because Congress was granted the express power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises by Article I, Section 8, which provides:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to be debts, and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.

The 16th Amendment would later specify that, “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration. Click here for a discussion of the 16th Amendment (and the legal treatment of direct/capitation tax v. indirect taxes) which was ratified in 1914 and clarified the constitutionality of a federal income tax.

Hylton v. United States: The Hylton case was the first federal case to raise the question of judicial review. Daniel Hylton of Richmond and other Virginia Republicans refused to pay the tax which they considered to be an unlawful direct tax which had not been properly apportioned under Article I, Section 9. The suit was instituted when Alexander Campbell, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Virginia, brought a debt action against Daniel L. Hylton to recover the hypothetical sum of $2,000. This specific sum was based on the tax that would have been owed on 125 chariots and the corresponding penalties necessary to give rise to the jurisdictionally required amount of $2,000.

The strategy for bringing two suits (one in state court and one in federal circuit court) was laid out in a letter dated January 28, 1795 from Hamilton to Tench Coxe, the Commissioner of Revenue and Assistant Secretary of Treasury. Hamilton recognized the desirability of obtaining an arrangement by mutual consent to accelerate the case to the Supreme Court, “the decision of which Tribunal can alone produce the acquiescence of the Executive in a determination agreeable to the hopes of the Defendants, it would be a pleasing thing and a man who opposes the tax upon a candid doubt could with an ill grace decline such an arrangement.”

Julius Goebel and Joseph Smith, in their multi-volume work, The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton: Documents and Commentary (1980), describe that at some point in the proceedings, “it was agreed that the government should pay all the expenses incident to Hylton’s taking the case on writ of error to the Supreme Court.” With the circuit court divided on the question, Hylton confessed to judgment (admitted liability) in order to test the constitutionality of the tax by appeal to the Supreme Court.

The extent of Congress’ taxing power was a contested question. During the debate in the House, James Madison declared that he objected to the tax as unconstitutional. By contrast, Representative Fisher Ames of Massachusetts expressed the Northern opinion that the carriage tax was an excise not a direct tax. The Act passed 49-22. Annals of Congress 726-730. Likewise, during the Virginia ratifying Convention, James Monroe and George Mason had challenged the wisdom of this Congressional power and proposed amendments including a quota system for federal collection of direct taxes and excises.

When Attorney General Bradford contacted Hamilton and sought to retain him to argue the case before the Supreme Court, Bradford expressed his opinion that the Hylton case was of utmost importance. Bradford’s July 2, 1795 letter to Hamilton explained:

I consider the question as the greatest one that ever came before that Court; & it is of the last importance not only that the act should be supported, but supported by the unanimous opinion of the Judges and on grounds that will bear the public inspection…I have therefore requested permission of the President for leave to call in auxiliary counsel & to invite you to join me in defence of the act. He thinks the measure very proper—and, you know, we will all be rejoiced to see you. This too will be a proper occasion for you to make your debut in the Supreme Court.

Hamilton traveled to Philadelphia to argue the case at the Supreme Court on February 24, 1796. He was paid the sum of $500 for his services and expenses. While in Philadelphia George Washington asked Hamilton to assist with the preparation of Washington’s Farewell Address.

Due to the important issues at stake, the federal government also retained counsel to represent Mr. Hylton. Jared Ingersoll (the Attorney General of Pennsylvania) and Alexander Campbell (the U.S. Attorney for Virginia) were also well qualified for the assignment. For his part, Campbell believed that the tax was unconstitutional but did not think that the Supreme Court had the authority to void the Act.

Hamilton’s papers contain two documents that illustrate his legal analysis, method and preparation. His “Brief respecting the Carriage Tax” is understood to be a working paper outlining his argument in the case. The brief sets forth one by one, the challenges to the constitutionality of the Act along with Hamilton’s counterarguments. The second document, Hamilton’s “statement of the material points of the Case” is a more formal legal document that Hamilton filed with the Clerk prior to oral argument.

Goebel and Smith describe Hamilton’s papers as follows in The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton:

Taken together, these documents sketch out the main lines of Hamilton’s argument: “What is the distinction between direct and indirect taxes” which was analyzed under the headings Legal, Clear Literal, Ascertained Theoretical sense, Practical sense, and Sense peculiar to the Constitution.

Hamilton of course emphasized the broad power of taxation granted to Congress. Hamilton had consistently advanced this position over the course of his career, which was fully set forth in his Report on the Constitutionality of the Bank. Hamilton’s brief explained that “Such a Construction must be made as that Power to tax may remain plenitude consistently with convenient application of the rule of Apportionment.” In his Statement of Material Points he argued that “In such case no construction ought to prevail calculated to defeat the express and necessary authority of the Government.” “It would be contrary to reason and to every rule of sound construction to adopt a principle for regulating the exercise of a clear constitutional power, which would defeat the exercise of the power.”

Hamilton also argued that the rule of apportionment for direct taxes could not be applied to a tax on carriages and an effort to do so would result in “absurd consequences” and gross inequalities. Hamilton also rejected the Republican states right concept of apportionment of quotas as “Fanciful, Oppressive & Inexecutable.” Among other authorities, Hamilton cited to Adam Smith’s definition of a direct tax in the Wealth of Nations. In a nutshell, Hamilton advanced a nationalist position, which he believed throughout his career was essential to a strong central government with robust taxing authority and implied powers.

In his opinion, Justice Chase acknowledged that the seeds for the issue of judicial review had been planted:

As I do not think the tax on carriages is a direct tax, it is unnecessary, at this time, for me to determine, whether this court, constitutionally possesses the power to declare an act of Congress void, on the ground of its being made contrary to, and in violation of, the Constitution; but if the court have such power, I am free to declare, that I will never exercise it, but in a very clear case.

Additional reading:

The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton: Documents and Commentary, Volume IV (Goebel & Smith, 1980)

Hylton case file (Library of Congress)

Alexander Hamilton’s papers (Library of Congress)

Supreme Court Opinion in Hylton v. United States

The Documentary History of the Supreme Court, Volume 7 (Maeva Marcus, 2003)

The Income Tax Amendment, Columbia Law Review, Volume X, page 380 (1910)

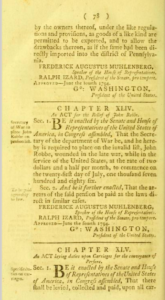

Pictured below is the Carriage Act adopted on June 5, 1794.