The Revised Statutes of the State of New York (1829)

In 1829, New York became the first common law jurisdiction to formally codify its laws. The Revised Statutes of the State of New York (otherwise known as the “Revised Statutes”) became a model for other states during the 19th Century “Codification Movement.” According to James Kent, a leading jurist at the time, the Revised Statutes “made great alterations in the law” which constituted “the most extensive innovations which have hitherto been the consequence of any single legislative effort.” Among other examples, the Revised Statutes contained important corporate governance reforms and legal protections for investors following the Wall Streets scandals of 1825, the first legislative enactment of the physician-patient privilege, and the complete elimination of slavery in the State of New York.

Statutory texts prior to 1829: Prior to the publication of New York’s Revised Statutes in 1829, statutes were generally organized by date not by subject matter. The states (and previously the colonies) published their statutes sequentially as legislative “session laws.” In the early 19th Century, the legislative session laws (or “Acts”) were the only official sources of statutory text. As time passed, researching the law on a given issue became increasingly problematic, to the extent that a lawyer could even locate the applicable and disjointed session laws. Because the British seized control of New York from the Dutch in 1664, legal research required pouring through nearly two hundred years of annual session laws.

An additional difficulty was that the inherited colonial laws were not only inaccessible but also often poorly drafted and prolix. As described by South Carolina Judge John F. Grimke in 1790, South Carolina’s statues were “wrapped in…a profound confusion and sibylline obscurity.” Connecticut Supreme Court Justice Zephaniah Swift had complained that “the jurisprudence of the country was surrounded by thick clouds of technical jargon and abstruse learning, that is inaccessible to the mass of the people.” Justice Swift proceeded to publish the first digest of Connecticut laws in 1795 and the first American legal treatise. Click here for a discussion of Swift’s System of Laws of the State of Connecticut. Click here for a discussion of Swift’s 1810 Treatise on the Laws of Evidence. While Swift’s works were historic in their own right, Swift’s secondary sources did not attempt to revise or codify the law. Click here for a link to Swift’s Digest of the Laws of the State of Connecticut (1822).

In the early 19th century, a condensed and updated statutory compilation was particularly important in New York, which was well on its way to becoming the “Empire State.” New York City was not only a national commercial and banking capital, it was also the country’s first political capital (although only briefly under the new federal Constitution). The population of the state almost tripled between 1800 and 1820, a growth rate higher than any of the original thirteen colonies. Between 1800 to 1821, New York banks exploded from a capitalization of $3.4 million to$21.1 million. In 1825, half of the nation’s imports were flowing through New York. The completion of the Eire Canal in 1825 only reaffirmed New York’s status. Not surprisingly, no other state had a comparable outpouring of legislation. The annual session laws of the New York legislature during this period averaged 300 pages each, compared to South Carolina which produced only 125 pages of new statutes annually.

The New York Revised Statutes attempted to boldly provide legal certainty by systematically codifying and reorganizing New York statutory law. Rather than just assembling and republishing voluminous and overlapping session laws, New York’s Revised Statutes of 1829 compiled, reorganized, reformed and simplified New York law in a single stroke.

The Revised Statutes‘ monumental codification efforts were inspired by English jurist and philosopher Jeremey Bentham’s codification movement. Bentham’s utilitarian theories rejected the concept of natural law and was critical of Blackstone. Bentham labeled judge-made common law as “ancestor worship,” which he considered arbitrary anti-democratic. Wienczyslaw Wagner, “Codification of Law in Europe and the Codification Movement in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century in the United States,” St. Louis University Law Journal (1953).

The Revision and Codification Process: The three “Revisors” who were selected by the New York Legislature were given near “plenary powers to redesign, reformulate and redevelop the whole body of New York statute law, which had been a century and a half in the making, to say nothing of received British statutes of a longer lineage.” Ultimately, the Legislature would have the final vote on whether or not to approve the revised law. Nevertheless, the broad mandate was “totally without precedent in Anglo-American legal history.” The Invention of Legal Research (Joseph Gerken, 2016).

Fortunately, the young lawyers who were ultimately selected, John Duer and William Alan Butler, rose to the occasion, considering their assignment to reformulate and organize a “symmetrical and scientific arrangement” of New York law. They outlined for the Legislature seven advantages of their proposed revision:

1) “It will reduce the statutes now in force, probably to one half of their present extent.”

2) “It will in most cases render them concise, simple, and perspicacious, as to be intelligible not only to professional men, but to persons of every capacity.”

3) “It will redeem [the statutory law] from the uncertainties and obscurities arising from the long and involved sentences, and from the intricate and obsolete diction…originally copied from English acts…”

4) It will include “tables and indexes” permitting greater “ease and certainty” for users.

5) “It will greatly facilitate the acquisition of knowledge of law as a science…”

6) “Its adoption supersedes the necessity of any future revision of the laws. Should any changes be found necessary or expedient, the legislature” need only enact new acts using the new organizational structure.

7) “Lastly, the successful execution of the proposed plan may not only lead to its imitation in our sister states, but it may also lay the foundation of other and still greater improvements.”

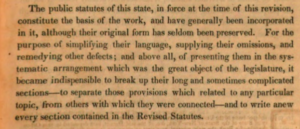

Four years later, after the revisions were reviewed and approved by legislative committees, the preamble to the published version summarized the result of their efforts:

Risks and Disadvantages of Statutory Codification: Of course, any effort to simplify or streamline the law runs the risk of weakening or overly simplifying important statutory nuances. For this reason, when New York Supreme Court Justice Kent praised the Revised Statutes, he also recognized that there was “cause of apprehension, on account of the depth to which the hand of reform has penetrated, in pursuit of latent and speculative grievances.”

Justice Kent understood that legal reforms ran the risk of erasing important and intricate legal doctrines. In the 1830’s the growing popularity of the “codification movement” and its “dazzling theory of codification” led Kent to warn that:

It ought never to be forgotten, that the great body of the people in every country, in their business concerns, are governed more by usages than by positive law. The learning concerning real property…appears likewise to be too abstract, and too complicated, to admit, with entire safety, of the compression which has been attempted, by a brief, pithy, sententious style of composition. There is a peculiar and inherent difficulty in the application of the new and dazzling theory of codification to such intricate doctrines, which lie wrapped up in principles and refinements, remote from the ordinary speculations of mankind. Brevity becomes obscurity, and a good deal of circumlocution has heretofore been indulged in all legislative productions; and reservations, provisoes, and exceptions, have been carefully inserted, in order that the meaning of the law-giver might be generally, and easily, and perfectly understood.

Thus, if taken too far and not done carefully, “legislation by codification becomes essentially the legislation of a single individual (the reviser).” Kent recognized that the drafters of the Revised States “have displayed great industry, intelligence, and ability; and it will not materially impair the credit to which they are entitled for the execution of the work.” Nevertheless, the danger of radical modifications was that “if some valuable matter should have been omitted, and a good deal of uncertainty and complexity be discovered to exist…[the new streamlined code could be] disturbing to their very foundations the usages and analogies of existing institutions.”

That said, the Revised Statutes was widely hailed as a success and exemplar for other states. Following New York’s Revised Statutes in 1829, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts followed suit in the 1830s and 1840s. New York federal judge Alfred Conkling would later describe the revisions to the New York penal code as, “One of the great excellencies of this branch of our written laws, consists in the brevity and precision of language in which it is expressed.” Approximately thirty years later, Judge Thomas Cooley conceded that he compiled Michigan laws “after the manner of the Revised Statutes of New York.”

Additional observations about the Revised Statues: Interestingly, the Revised Statutes begins with the Articles of Confederation from 1781 and a copy of the United States Constitution from 1789. Of course, by 1829 the Articles of Confederation had long become a historical artifact. Nonetheless, by including these underlying sources of federal law the Revised States paid respect to our federal system of overlapping dual sovereignty.

It is also noteworthy that the Revised Statutes contained the first statutory enactment of the physician-patient privilege. 75. N.Y. REV. STAT. 1829 II, 406, part III, tit. 3, ch. VII, art. VIII, § 79. The 1828 law adopting the highly significant evidentiary privilege provided:

No person duly authorized to practice physic or surgery, shall be compelled to disclose any information which he may have acquired in attending any patient, in a professional character, and which information was necessary to enable him to prescribe for such patient as a physician, or to do any act for him, as a surgeon.

In recognition of the significance of New York’s Revised Statutes, it was widely cited by French commentator, Alex de Tocqueville, in his historic chronicle of America, Democracy in America (First American edition, 1839). Similarly, in James Kent’s Commentaries on American Law, Kent explained why he dedicated so much attention to discussion of New York’s Revised Statutes. Kent presumed that “I need not apologize to the American student for attracting his attention so frequently to the statute law of a particular state,” given the “extensive innovations” in the Revised Statutes. James Kent, Commentaries on American Law (1840).

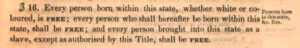

By 1829, New York had also led the way in finally abolishing slavery. The New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785 by 31 such luminaries as John Jay and Alexander Hamilton. Fourteen years later, the first New York law providing for gradual abolition was eventually passed in 1799. The imperfect Act provided that children of slaves born after July 4, 1799 would be legally free, but would be required to serve as indentured servants until age 28 for males and age 25 for females. Slaves born prior to 1799 were treated as indentured servants for life. In 1817, New York finally freed all slaves born before July 4, 1799. The 1817 law would become fully effective ten years later in 1827. Thus, the New York Revised Statutes of 1829 was the first codification to fully extirpate the odious institution from New York law in Section 16, of Title VII, which is copied below:

Business and Wall Street reforms: The Revised Statutes contain a number of regulatory provisions governing Wall Street financial firms and their directors that were designed to protect the interests of investors. Many of these regulations prohibited stock manipulation and financial fraud. For example, the Revised Statutes attempted to prohibit fraudulent exchanges of securities between corporations; prohibited fraudulent purchases of a corporation’s own stock (except when using profits); prohibited corporate loans to stockholders and directors; mandated that certain corporate actions required a resolution of the entire board; created enforcement mechanisms for violations, including allowing investors in a fraudulent corporation to use courts to shut down operations and recover assets (the ability of minority shareholders to sue directors was the predecessor to today’s shareholder derivative suits); and provided for criminal penalties and personal liability for directors. The Revised Statutes also required financial corporations to transmit annual financial statements to the state comptroller. A particularly controversial reform presumed that every corporate insolvency was fraudulent, placing the burden of proof to the contrary on directors. This reform was criticized as draconian and later repealed, but did signal a willingness to hold executives accountable following Wall Street’s first major scandal in 1826.

Arguably, Wall Street’s first corporate governance crisis and scandal in 1826 provided momentum for adoption of the Revised Statutes. The Panic of 1825, which began in England, is beyond the scope of this post. A quick summary of the 1826 Wall Street scandal is copied below:

In July of 1826, several prominent Wall Street firms abruptly went bankrupt, amid scandalous revelations of fraudulent financial practices by their management. Although mostly forgotten today, these events represented a watershed in the early development of the corporation laws and investor protections governing Wall Street: in the aftermath of the scandals, New York State enacted an extensive package of legislation designed to protect the interests of investors. These statutes were some of the the very first of their kind, and had a lasting influence. Eric Hilt, Wall Street’s First Corporate Governance Crisis: The Panic of 1826 (2009).

Additional reading;

The Invention of Legal Research (Joseph Gerken, 2016)

The American Codification Movement: A Study of Antebellum Legal Reform (Charles Cook, 1981)

A Government of Laws Not of Precedents 1776-1876: The Google Challenge to Common Law Myth, John Maxiner, 4 Brit. J. Am. Legal Stud. 137 (2015)

Eric Hilt, Wall Street’s First Corporate Governance Crisis: The Panic of 1826 (2009)

James Kent, Commentaries on American Law (1840)

Click here for a link to volume 1 of the Revised Statutes:

Click here for a link to volume 2 of the Revised Statutes:

Click here for a link to volume 3 of the Revised Statutes:

Index of historic codifications of New York statutes (New York State Library)

You can purchase a paperback copy of the Revised Statutes of 1829 from Amazon by clicking on the following link:

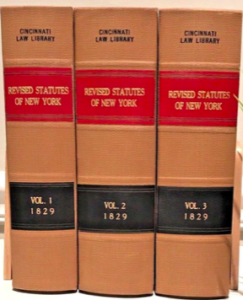

The Revised Statues of 1829 is pictured below:

FOR SALE

You can purchase a rare copy of the Laws of New York 1777-1779 (3 volume set printed during the Revolutionary War) which is offered for sale for $1,350 on ebay (which is accepting “best offers”).

The historic laws have been rebound with typical library stamping and markings.

Click here to view the item using the following Ebay link: 1777-1779 Laws of the State of New York 3 Volume Set Revolutionary War Books | eBay

FOR SALE

1829 – The Revised Laws of the State of New York, 3 volume set. Listed for $510 at This Old Book shop.

Original leather with scuffing and wear to the covers; especially along spine. Wear to head/tail of spines. Corners bumped and slightly worn. Foxing throughout. Hinges cracked but still secure. Previous owners stamp on front free endpapers. A beautiful, rare set! #FG/AB

Click here to view the item for sale at the following Ebay link 1829 The Revised Statute of the State of New York – 3 Volume Set | eBay