The History of Executive Orders

Two months after being inaugurated, George Washington issued his first Executive Order on June 8, 1789. Although the term “Executive Order” does not appear in the Constitution, every President has issued Executive Orders, with the exception of President William Henry Harrison (who died of pneumonia shortly after taking office). While some Executive Orders have been highly controversial, other Executive Orders have proven to be essential.

George Washington’s First Executive Order

During his Presidency George Washington issued what can loosely be described as eight “Executive Orders.” The first was issued by letter dated June 8, 1789 asking executive department heads to provide “a full precise, and distinct general idea of the affairs of the United States” they oversaw.

When Washington was sworn in on April 30, 1789, the newly created Federal government replaced the weak “perpetual union” of states which had operated under the Article of Confederation. Years earlier, in a letter to Virginia Governor Benjamin Harrison dated 1/18/1784, George Washington expressed his concern for the consequences that would result from “a half starved, limping Government, that appears to be always moving upon crutches, & tottering at every step.”

The First Congress would begin by establishing the Department of Foreign Affairs on July 27, 1789, the Department of War on August 7, 1789 and the Treasury Department on September 2, 1789. Prior to the creation of these executive branch departments, President Washington issued his first Executive Order to the predecessor departments that existed under the Articles of Confederation and had held over to assist the newly forming Washington administration.

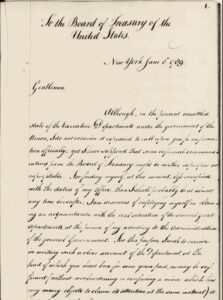

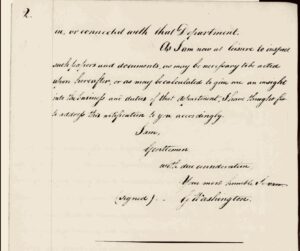

In what can be described as a “request” for information to acting Secretary of Foreign Affairs John Jay, Washington’s June 8, 1789 Executive Order described the as yet “unsettled state of the Executive Departments” under the new Constitution. Washington explained that he was “desirous of employing myself in obtaining an acquaintance with the real situation of the several great Departments, at the period of my acceding to the Administration of the general Government.” In setting forth his “wish” Washington wrote:

For this purpose I wish to receive in writing such a clear account of the Department at the head of which you have been, as may be sufficient (without overburdening or confusing a mind which has very many objects to claim its attention at the same instant) to impress me with a full, precise & distinct general idea of the United States, so far as they are comprehended in, or connected with that Department.

Copies of letter were also sent to the acting Secretary of War, The Board of Treasury and the acting Postmaster General. Pictured below is a copy of Washington’s letter to the Board of Treasury, as recorded in Washington’s letter book.

The Board of Treasury promptly responded on June 9 that the three members were honored to receive Washington’s letter. They advised that:

It will require some days to make out the necessary Documents, to which such an account must necessarily refer; these are now preparing, and shall, from time to time, be transmitted under their distinct heads, in order that the statement may be more clearly understood.

On June 10, the Board of Treasury submitted their first of several reports. Likewise, on June 9, Secretary of War, Henry Knox, responded that he would “immediately proceed” to prepare the requested information. New cabinet secretaries would not be appointed until later in the year, after legislation creating their departments was adopted by Congress. Secretary of State John Jay continued to serve until Thomas Jefferson assumed the job in March of 1790. Jay would be appointed the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Henry Knox was reappointed to continue serving as Secretary of War. Click here for a discussion of the Act Establishing the War Department. The three members of the Treasury Board, Samuel Osgood, Walter Livingston and Arthur Lee continued serving until September 11 when Alexander Hamilton was appointed.

The government under the Articles of Confederation has been described as a “nightmare” by historian Ralph Clark Chandler. For example, due in part to the limited authority of the Department of Foreign Affairs, John Jay warned of dire consequences in a letter to Washington on June 27, 1786:

Our affairs seem to lead to some crisis—some Revolution—something that I cannot foresee, or conjecture. I am uneasy and apprehensive—more so, than during the War—Then we had a fixed Object, and tho the means and time of attaining it were often problematical, yet I did firmly believe that we should ultimately succeed, because I was convinced that Justice was with us. The Case is now altered—we are going and doing wrong, and therefore I look forward to Evils and Calamities, but without being able to guess at the Instrument nature or measure of them. That we shall again recover, and things again go well, I have no Doubt—such a variety of circumstances would not almost miraculously have combined to liberate and make us a Nation for transient or unimportant Purposes—I therefore believe we are yet to become a great and respectable People—but when or how, the Spirit of Prophecy only can discern.

At the time, Jay was documenting the failure of individual states to comply with their treaty obligations. Another example of the chaos confronting the old Confederation Congress was the issue of duties on trade imposed by the states. After Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New Hampshire imposed restrictions on British trade in the hope of extracting concessions, Connecticut responded by allowing unrestricted trade with Britain, while imposing tariffs on Massachusetts.

Washington’s subsequent Executive Orders (including the Thanksgiving Day Proclamation and the Neutrality Proclamation)

Washington’s second executive action was the more famous Thanksgiving Day Proclamation of October 3, 1789 calling for a national day of Thanksgiving on Thursday, November 26.

Washington’s Thanksgiving proclamation was distributed to state governors, with the request that governors announce and observe the day within their respective states. Washington marked the day by attending services at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City. Recognizing that he was a national symbol, Washington donated beer and food to imprisoned debtors in New York, the nation’s first capitol. Click here for a discussion of the “First” Thanksgiving and Washington’s Thanksgiving Proclamations.

In its day, Washington’s June 1789 request to the federal government’s department secretaries was not officially called an Executive Order, as the modern term would not be used until the Lincoln administration. Likewise, Washington’s Thanksgiving proclamation would not be considered a formal Executive Order today.

Washington’s other executive actions included an August 26, 1790 directive ordering compliance with Native American treaty obligations. Washington explained that it had become necessary to warn American citizens of treaty violations with the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribes. The proclamation commands “all officers of the United States” both civil and military, “and all other citizens and inhabitants thereof, to govern themselves according to the treaties and act aforesaid, as they will answer the contrary at their peril.”

In 1791 Washington issued orders and proclamations involving the survey to establish the boundaries of the District of Columbia and later defining and the District’s boundaries. To keep America from becoming entangled in European wars against France, Washington issued his Neutrality Proclamation on April 22, 1793 which provided for the United States to be “friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers” as follows:

Whereas it appears that a state of war exists between Austria, Prussia, Sardinia, Great-Britain, and the United Netherlands, of the one part, and France on the other, and the duty and interest of the United States require, that they should with sincerity and good faith adopt and pursue a conduct friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers:

I have therefore thought fit by these presents to declare the disposition of the United States to observe the conduct aforesaid towards those powers respectively; and to exhort and warn the citizens of the United States carefully to avoid all acts and proceedings whatsoever which may in any manner tend to contravene such disposition.

And I do hereby also make known that whosoever of the citizens of the United States shall render himself liable to punishment or forfeiture under the law of nations, by committing, aiding or abetting hostilities against any of the said powers, or by carrying to any of them those articles, which are deemed contraband by the modern usage of nations, will not receive the protection of the United States, against such punishment or forfeiture: and further, that I have given instructions to those officers, to whom it belongs, to cause prosecutions to be instituted against all persons, who shall, within the cognizance of the courts of the United States, violate the Law of Nations, with respect to the powers at war, or any of them.

Among others, James Madison criticized Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation as an overextension of executive authority infringing on Congress’s power to decide issues of war and peace. The following year, Congress passed the Neutrality Act of 1794, ratifying the Neutrality Proclamation and giving Washington the authority to prosecute violators. Yet, this early example demonstrates that the President and Congress have overlapping responsibilities in a system of checks and balances.

In August of 1794 during the Whiskey Rebellion President Washington commanded insurgents in Western Pennsylvania to “disperse and retire peaceably”. In September Washington signed a proclamation authorizing military intervention and summoning into service the militias in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. Thereafter Washington led a military force to quell the insurrection. The following year, he pardoned those who had been arrested. Click here for a discussion of the Whiskey Rebellion.

Constitutional Basis for Executive Orders

Presidential authority to issue Executive Orders is largely based on the Take Care and Vesting clauses in Article II of the Constitution.

Article II, Section 1 (the Vesting clause) provides that “[t]he executive power shall be vested in a President.”

Article II, Section 3 (Take Care clause) provides that the President “shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed…”

Moreover, as Commander in Chief the President has implied powers. Article II, Section 2, also permits the President to “require the opinion, in writing, of the principal officer in each of the executive departments, upon any subject relating to the duties of their respective offices…”

While critics have labeled Executive Orders “legislation by other means,” supporters defend their favorite Executive Orders as a necessary tool in the face of Congressional intransigence.

Among other reasons, Executive Orders can be controversial because they are not legislation adopted pursuant to Article I’s bicameralism and presentment requirements. As much as executive power is vested in the President, all legislative power is vested in Congress under Article I, Section 1 which provides that:

All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

Presidential Statistics

- FDR, who was elected to four terms, issued more Executive Orders than any other president (3,728). Roosevelt is also the only president to average more than 300 per year.

- William Henry Harrison is the only president to have never issued an Executive Order.

- John Adams, James Madison and John Monroe issued the fewest executive orders in a complete term (one).

- President Grant was the first president to issue more than 100 Executive Orders. In 1873 Grant issued an Executive Order setting forth guidelines for issuing Executive Orders, which today are reviewed by the Office of Management and Budget and the Attorney General before execution by the President.

- President Roosevelt was the first president to issue more than 1,000 Executive Orders.

In 1907, the State Department began retroactively numbering Executive Orders back to the Lincoln administration in 1862. The Federal Register Act of 1936 formalized the process, requiring publication in the Federal Register. To date, nearly 14,000 Executive Orders have been issued. Click here for a running list of Executive Orders maintained by the American Presidency Project.

Listed below are examples of Executive Orders that are universally acknowledged to have been important:

- President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation issued in 1862 to take effect on January 1, 1863.

- FDR’s Manhattan Project during World War II (Executive Order 8807 in 1941 established the Office of Scientific Research and Development)

- FDR’s Works Progress Administration, enacted by Executive Order 7034 in 1935

- President Truman’s desegregation of the American military in 1948 by Executive Order 9981 (declaring it “to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.”)

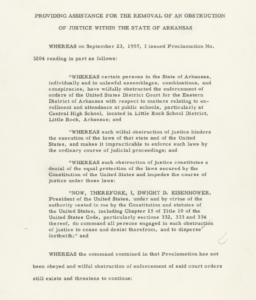

- President Eisenhower’s mobilization of the 101st Airborne Division with Executive Order 10730 to integrate Central High School in Arkansas (The Little Rock Nine) in 1957

- President Kennedy’s creation of the Peace Corp by Executive Order 10924 in 1961.

Pictured above is Eisenhower’s E.O. 10730 which enforced the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

Listed below are examples of Executive Orders that have been controversial and in some cases clear mistakes:

- President Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War in 1861

- FDR’s internment of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II with Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942

- President Truman’s Executive Order 10340, which placed all U.S. steel mills under Federal control during the Korean War, resulting in the Supreme Court case of Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer

Additional Reading:

Washington’s letter book (Library of Congress)

Executive Orders: Issuance, Modification, and Revocation (Congressional Research Service)

Presidential Directives: Background and Overview (Congressional Research Service)

Table of Executive Orders by President (The American Presidency Project)

Public Administration under the Articles of Confederation, Ralph Clark Chandler (1990)