The American Museum (published by Mathew Carey, 1787-1792)

The American Museum was a monthly magazine with a national audience published in Philadelphia in the late-18th century by Mathew Carey. The pioneering publication was one of the first successful American literary magazines. While the American Museum was only published for six years, it chronicled some of the most important events in American history.

Mathew Carey founded the American Museum using a $400 loan from none other than the Marquis de Lafayette. During its publication, Carey printed a total of 72 monthly issues (which were later bound into twelve volumes). The publication ran every month from January 1787 through December 1792. During this period, the magazine re-printed many of the most significant historical documents in the American political canon, alongside original works written for the magazine.

Fortuitously, Carey created the American Museum in 1787, the year that the Constitution was written in Philadelphia. As such, the magazine contains a copy of the Constitution printed in the September of 1787 edition. Carey also reprinted the famous debates leading to the Constitution’s ratification in 1788. In 1789, the American Magazine reported the proceedings of the first Congress, along with the debates over the adoption of the Bill of Rights.

Copied below is the September 1787 publication of the Constitution, along with Federalist I , which appeared in the November 1787 edition:

Recognizing that Hamilton, Madison and Jay addressed the Federalist papers to the “people of the state of New York,” historians have debated the impact of the essays in other states. Nevertheless, the American Museum was the first instance of the Federalist papers being published in Philadelphia, where the Constitution was drafted. The November edition of the American Museum was also one of the first periodicals outside of New York to reprint Federalist essays.

It is also clear that the America Museum enjoyed readers around the nation, as is evidenced by its subscribers who resided in almost every state. Pictured below is a page from the subscriber list, capturing both Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr among the named subscribers from New York.

In addition to political tracts, the American Museum also printed a wide range of other Americana including poetry and prose. As such, it became one of the first American periodicals to recognize emerging American literature and culture, separate from European content.

The magazine also contained rare engravings and maps, some of which are copied below, including Benjamin Franklin’s “Chart of the Gulf Stream” and the nauseating “Plan of an African Ship’s Lower Deck.” Although it may have alienated southern subscribers, Carey did not shy away from printing anti-slavery tracts.

As editor and publisher, Carey sought to republish and “preserve the most valuable” of the pamphlets, essays and papers which “reflected credit on their authors, as well as this country.” Carey explained in his preface to the first edition that he did not limit himself to recent material, but also included work that appeared “prior to and during the war….” Among the contributors featured in the magazine were Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, and Noah Webster. It is not surprising that Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was printed in the inaugural edition in January of 1787, along with critiques of the Articles of Confederation.

Given the otherwise “perishable nature of the vehicles that contained them,” Carey happily assumed the role of curator and publisher. He acknowledged that his new magazine was “destitute. . . of originality…” He also suggested that the collection might be enriched by recurring occasionally to European publications “calculated to promote the cause of liberty, religion, and virtue.” Click here for a link to Volume 1.

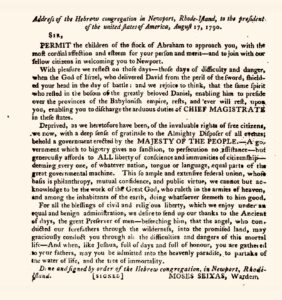

In June of 1791, Carey printed Moses Saixas’ famous “Address of the Hebrew Congregation in Newport in Rhode-Island to the president of the united states of America” which is copied below. President Washington’s reply dated August 18 to the Newport Congregation (known as the Touro Synagogue) contains one of the most powerful expressions of religious freedom for the new nation:

For happily the Government of the United States gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support….

In the final year of its publication, the American Museum printed a full copy of Alexander Hamilton’s important Report on the Subject of Manufactures, which is the earliest complete American printing of the report for the public.

In an advertisement for the magazine, Carey quoted an admiring George Washington who observed, “That a more useful literary plan has never been undertaken in America, or one deserving of public encouragement.” Washington observed that “I consider such easy vehicles of knowledge, more happily calculated than any other, to preserve the liberty, stimulate the industry and meliorate the morals of an enlightened and free People.” Click here for a link to George Washington’s June 25, 1788 letter to Carey:

Although I believe “the American Museum” published by you, has met with extensive, I may say, with universal approbation from competent Judges; yet, I am sorry to find by your favor of the 19th that in a pecuniary view it has not equalled your expectations.

A discontinuance of the Publication for want of proper support would, in my judgment, be an impeachment on the Understanding of this Country. For I am of opinion that the Work is not only eminently calculated to dissiminate political, agricultural, philosophical & other valuable information; but that it has been uniformly conducted with taste, attention, & propriety. If to these important objects be superadded the more immediate design, of rescuing public Documts from oblivion: I will venture to pronounce, as my sentiment, that a more useful literary plan has never been undertaken in America, or one more deserving public encouragement. By continuing to prosecute that plan with similar assiduity and discernment, the merit of your Museum must ultimately become as well known in some Countries of Europe as on this Continent; and can scarcely fail of procuring an ample compensation for your trouble & expence.

Although Carey succeeded in reaching wide circulation, the American Museum ultimately was not profitable. In 1792, Congress passed a postal law subsidizing newspapers, but excluding bulkier magazines. As a result, Carey suspended publication and moved into the ultimately more successful trade of printing and selling books.

In his autobiography Carey wrote that, “I was much attached to this work and had great reluctance to abandon it, unproductive and vexatious as was the management of it.” As described by historian Lyon N. Richardson in 1931, Carey “accomplished his aim remarkably well, considering practical limitations. . . He made of his magazine a true museum.”

Among the authors featured by Carey were the following, in no particular order:

- Thomas Paine

- Benjamin West

- Ezra Styles

- Benjamin Rush as Nestor

- Tench Coxe

- Philip Frenau

- David Humphreys

Among the seminal works published during the ratification debate were:

- Ben Franklin’s speech on the last day of the Constitutional Convention

- James Wilson’s October 6, 1787 address to the citizens of Philadelphia

- Curtius address to all Federalists

- Roger Sherman and Oliver Elsworth’s letter to the Governor of Connecticut explaining their support for the Constitution

- George Mason’s objections and reasons for not signing

- Elbridge Gerry’s letter setting forth his reasons for not signing the Constitution

- Federalist 1 – 7

- The Constitution’s cover letter (click here for a discussion of the Constitution’s Cover Letter)

The above links are all from John Adams’ personal copy of the American Museum published in 1787. Click here for a link to all twelve volumes.

Samples of other works published in the magazine include:

- The Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom

- Observations on the Insurrection in Massachusetts (Shay’s Rebellion)

- A Sermon on Dueling

- Thomas Jefferson’s Report on Coins

- Benjamin Franklin’s “Address to the Public from the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes, unlawfully held in Bondage.”

Mathew Carey the printer

Carey was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1760, where he edited an anti-British newspaper. After being exiled to France, Carey worked as an apprentice at a small press in the Parisian suburb of Passy with Ben Franklin. Franklin and Carey printed work for the American revolutionary cause at the French royal court.

At the time, the Marquis de Lafayette had returned to France to help plan a French invasion of Ireland. Lafayette frequently visited Franklin’s press at Passy where Carey and Lafayette became acquainted. This contact would prove invaluable years later when Lafayette loaned Carey the seed capital to start the American Museum.

While the American Museum was not profitable, it established Carey as a leading printer of his day. According to Carey, “Never was more labour bestowed on a work, with less reward. During the whole six years, I was in a state of intense penury. I never at any one time, possessed 400 dollars—and rarely three or two hundred…. I was, times without number, obliged to borrow money to go to market…”

Nevertheless, Carey developed a distribution network and contacts that were priceless. The lessons Carey learned with the American Museum were a springboard to his success in book publishing. For example, in later years he produced a popular Catholic Bible and several best-selling schoolbooks.

In 1791, Carey organized the Philadelphia Company of Printers and Booksellers. By 1800, Carey and Massachusetts publisher Isaiah Thomas had become the nation’s foremost printers with a national clientele. Click here for a discussion of patriot publisher Isaiah Thomas. By 1817, Carey’s press was the largest publisher in the United States.

During the War of 1812, New England Federalists who were dissatisfied with President Madison’s policies and the progress of the war secretly met in Hartford Connecticut and raised the possibility of secession. Ultimately, the delegates to the controversial Hartford Convention adopted an aggressive states’ rights stance and expressed their grievances in a series of resolutions. In an effort to unify the nation and promote public confidence, Carey published The Olive Branch: or, Faults on Both Sides, Federal and Democratic, A Serious Appeal on the Necessity of Mutual Forgiveness and Harmony in April of 1815. The purposely non-partisan treatise attempted to unify the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans. The Olive Branch was well received and eventually rivaled Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in popularity.

As described by Nancy Spannaus, author of Hamilton v. Wall Street and editor of the blog Americansystemnow.com:

Carey took extremely seriously President Washington’s Farewell Address, and the need for maintaining the unity of the nation. He excoriated both parties, but especially the Federalists of that decade, for losing sight of Washington’s perspective, and thus endangering the nation’s survival. The first Olive Branch exhaustively documents the failures and outright evils, even treason, committed by the parties, through the reprinting of letters, petitions, and other primary sources.

Click here for link to Spannaus’ blog about Carey’s effort to revive Hamiltonian economics.

In his later years, Carey wrote on various social and political topics, including economics, and the need for extending American naval strength to resist the British. Northern manufacturers embraced Carey’s protective tariffs, while Southerners burned him in effigy in Columbia, South Carolina.

Beginning with the outbreak of yellow fever in Philadelphia in 1793, Carey wrote A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia, representing an early foray into medical publishing. He would eventually publish dozens of medical works.

During his post-American Magazine publishing career, Carey printed novels and other work by Mason L. Weems, James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe, and Sir Walter Scott, among others. Carey did not limit his operations to books, printing broadsides, atlases, bibles, and political titles. Carey personally wrote Vindiciae Hibernicae (1819) promoting Irish history and nationalism, New Olive Branch (1820) discussed above, and Essays of Political Economy (1822) which explored Alexander Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures and other nation building proposals.

Carey was a member of the American Philosophical Society and the Franklin Institute. He served as a director of the Bank of Pennsylvania and the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal company. He was a founder of the Hibernian Society, an organization formed to provide aid to Irish immigrants. He also served on the “Committee of 24” that promoted canal-building in the 1820s and was a member the “friends of Clay” that supported Henry Clay’s presidential candidacy in 1824.

Additional Reading:

Autobiography of Mathew Carey (1835)

A History of Early Magazines (Lyon N. Richardson, 1931)

Mathew Carey, Publisher and Patriot (James N. Green, 1985)

Ben Franklin Was the First to Chart the Gulf Stream (Smithsonianmag.com)

George Washington and his letter to the Jews of Newport (Touro Synagogue National Historic Site)

Mathew Carey Revived Hamiltonian Economics, Nancy Spannaus (AmericanSystemNow.com)

Mathew Carey (1760 – 1839), Philadelphia Publisher and Provocateur (Library of Congress blog)