Senate Rejects John Rutledge’s nomination as Chief Justice in 1795

In the polarized environment of 21st Century American politics, Supreme Court vacancies have become increasingly politicized. With each nomination, the historical record is reexamined to determine the criteria to evaluate otherwise qualified nominees. Some may be surprised to learn that the first example of the Senate rejecting a Supreme Court nominee occurred at the end of President Washington’s second term.

The Senate established an important precedent when it rejected John Rutledge’s nomination to serve as Chief Justice on December 15, 1795. The decision to “negative” Rutledge’s nomination was largely based on his political views regarding Jay’s Treaty, in the year leading up to the election of 1796. There may also have been concerns over Rutledge’s mental status, which would be further called into question when he attempted suicide following the vote.

Advice and Consent

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution (known as the “Appointments Clause”) provides that the President shall nominate Supreme Court Justices with the “Advice and Consent” of the Senate as follows:

[The President] shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.

The phrase “Advice and Consent” is used twice in the Appointments Clause describing the President’s powers, but does not appear again in the Constitution in either Article I or Article III. This begs the question of what does “Advice and Consent” mean. The evolving answer has been established by precedent, starting with the Washington administration.

The concept of advice and consent dates back to Great Britain. When the Constitution was drafted, some framers believed that the Senate’s role was to advise after the President made a nomination. Others, including Roger Sherman, suggested that advice was useful prior to a nomination. As President, Washington took the position that pre-nomination advice was permitted but not mandatory.

In Federalist numbers 75 and 76, Alexander Hamilton argued that the concept of advice and consent provided an important safeguard through the mechanism of checks and balances. In Federalist 76, Hamilton asked:

To what purpose then require the co-operation of the Senate? I answer, that the necessity of their concurrence would have a powerful, though, in general, a silent operation. It would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the President, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from State prejudice, from family connection, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity. In addition to this, it would be an efficacious source of stability in the administration.

Hamilton acknowledged that the “negative” by the Senate had potential drawbacks. The Senate had no guarantee that a second nomination “would present a candidate in any degree more acceptable to them; and as their dissent might cast a kind of stigma upon the individual rejected, and might have the appearance of a reflection upon the judgment of the chief magistrate…” For these reasons, Hamilton did not think it likely that “their sanction would often be refused, where there were not special and strong reasons for the refusal.”

John Rutledge’s Background

John Rutledge was unquestionably one of the most qualified nominees for the position of Chief Justice in American history. Yet, his nomination for Chief Justice would be defeated by a 14-10 vote in 1795.

To begin with, Rutledge was a signer of the Constitution who was an active participant at the Constitutional Convention. He chaired the Committee on Detail (with Edmund Randolph, Oliver Ellsworth, James Wilson and Nathaniel Gorham) which wrote the first draft of the Constitution. Rutledge attended all sessions of the Convention and served on multiple committees.

Rutledge was also one of the drafters of South Carolina’s first constitution. In 1779, he served as the state’s first Governor after declaring independence. During the depths of the Revolutionary War, he exercised emergency powers and oversaw the rebuilding process when the war ended. Years earlier Rutledge served as a delegate to the Stamp Act Congress in 1765. He continued representing South Carolina in the First and Second Continental Congress.

After the Constitution was ratified, newly elected President Washington appointed Rutledge an associate justice to the Supreme Court on September 26, 1789. Rutledge served on the Supreme Court from 1789 until 1791, when he stepped down for a higher paying job as Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court.

It is unclear whether disappointment at not being offered the position of Chief Justice played any role in his decision to step down. Nevertheless, it is likely that deteriorating health, and the physical demands of “circuit duty” contributed to his decision to resign in 1791. At the time, Supreme Court Justices were required to travel the nation twice a year as circuit judges. Rutledge was responsible for the Southern Circuit, which was the most remote and difficult to travel. In fact, Rutledge’s successor as Associate Justice responsible for the Southern Circuit, Justice Thomas Johnson, quit after only five months.

Second Nomination by Washington for Chief Justice in 1795

John Jay served as Chief Justice from 1789 to 1795. When Jay stepped down as Chief Justice to become Governor of New York, Rutledge wrote to Washington offering his name for nomination to rejoin the Court to replace Jay as Chief Justice. In a letter dated June 12, 1795 to Washington, Rutledge explained that when Washington appointed Jay Chief Justice in 1789, many considered Rutledge equally if not more qualified. According to Rutledge:

my Pretensions to the Office of Chief Justice were, at least, equal to Mr Jay’s, in point of Law-Knowledge, with the Additional Weight, of much longer Experience, & much greater Practice

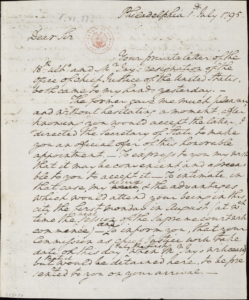

Washington promptly wrote back to Rutledge on July 1, 1795 and offered him the job of Chief Justice. Because the Senate wasn’t in session, the temporary nomination was a “recess appointment” until the Senate could confirm the nomination. Washington’s letter to Rutledge located at the Library of Congress is pictured below.

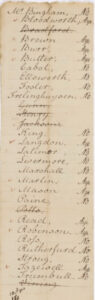

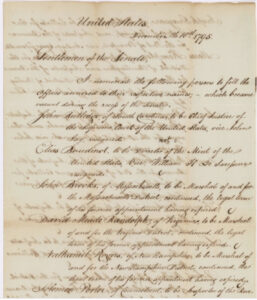

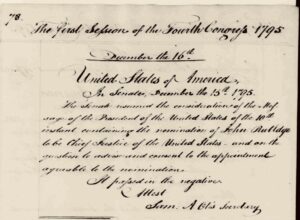

Copied below is Washington’s formal message to the Senate nominating Rutledge on December 10, 1795:

Jay’s Treaty and Rutledge’s July 16 speech in Charleston

After Jay’s resignation, Rutledge became the nation’s second Chief Justice under a recess appointment effective immediately on July 1, 1795. Approximately two weeks later, on July 16, 1795, Rutledge gave a highly controversial speech in Charleston that would end his career in the Washington administration.

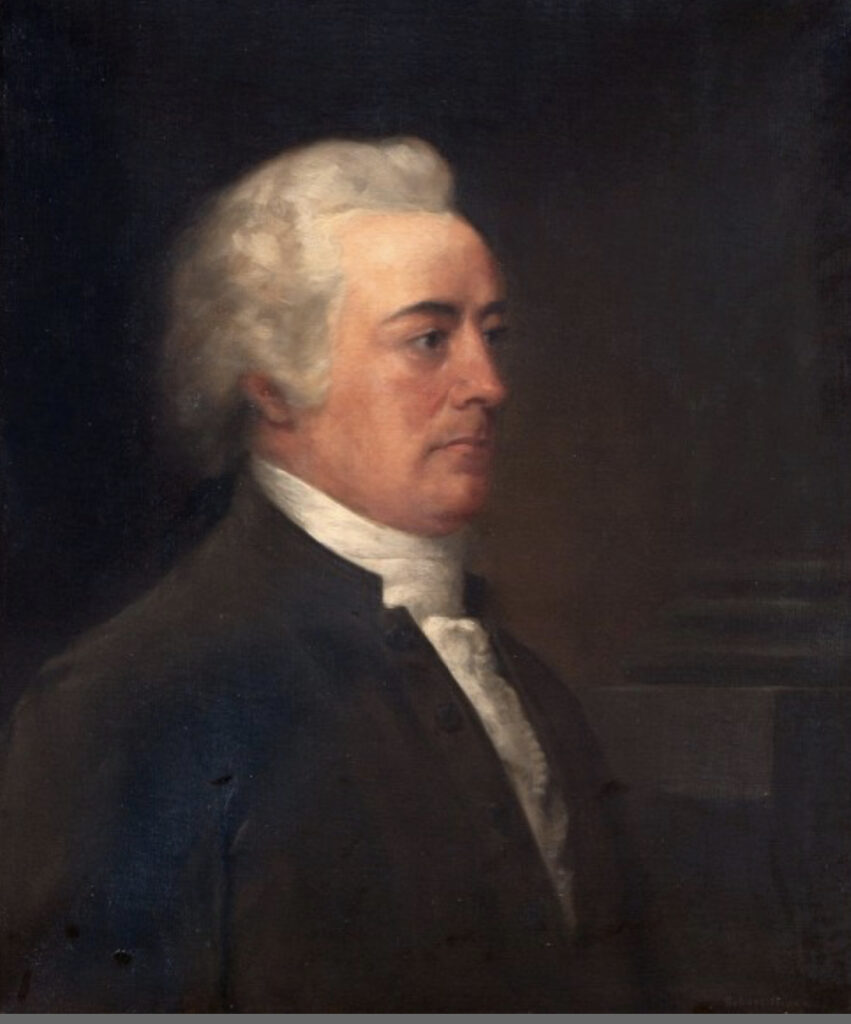

Jay’s Treaty was signed in England on November 19, 1794. The treaty attempted to resolve outstanding issues between the U.S. and Great Britain that remained in dispute following the Revolutionary War. Click here for a detailed discussion of Jay’s Treaty. Chief Justice John Jay is pictured below.

President Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London to negotiate the treaty in 1794 after war broke out between England and France in 1793. President Washington presented the Treaty for ratification to the Senate in June of 1795. When the details of the treaty became public, it set off a firestorm of protests around the nation. The treaty was narrowly ratified by the Senate on June 25, by the minimum required 2/3 majority vote of 20-10.

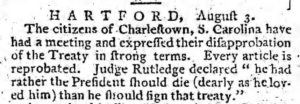

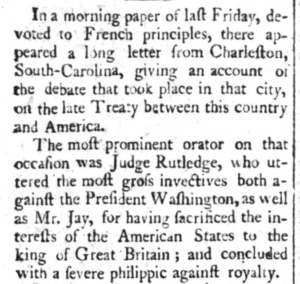

On July 16, 1795, Rutledge gave an ill-advised speech at St. Michael’s Church in Charleston denouncing the Jay Treaty. Among other things, Rutledge was alleged to have stated “that he had rather the President should die, dearly as he loved him, than he should sign that puerile instrument” and that he “preferred war to an adoption of it.”

The speech was widely reported in the press and provoked an intense reaction by the Treaty’s Federalist supporters who viewed Rutledge’s intemperate remarks as a slight to the Washington administration. It is also possible that the contents of the speech were exaggerated in the bitter environment.

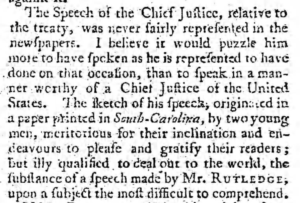

Pictured below is an article defending Rutledge. The article suggests that he was “never fairly represented” by the initial reporting on his speech in the South Carolina papers.

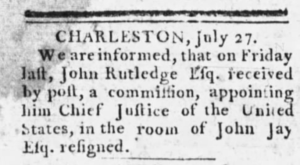

It is not clear when Rutledge received Washington’s July 1 letter. It is therefore possible that he did not know that he had been nominated when he gave his July 16 speech. Regardless of when he received official word of the nomination, Rutledge arguably should have recognized that the treaty was a sensitive topic. Pictured below is newspaper article from late July reporting on Rutledge’s appointment.

As described by historian James Haw, “Rutledge had unwittingly put himself in outspoken opposition to a major initiative of the administration that had just nominated him to high office.”

Nevertheless, Rutledge maintained ostensible support from President Washington who declined to withdraw Rutledge’s nomination. Upon arriving in Philadelphia, Rutledge presided as Chief Justice over the August term of the Supreme Court as a recess appointee.

The day before the Senate vote, Alexander Hamilton shared his thoughts on the Rutledge nomination in a letter dated December 14 to New York Senator Rufus King:

Reflection upon this in its various aspects weighs heavily in my mind against Mr R, upon the accounts I have received of him, and balances very weighty consideration the other way.

The Vote

When the Senate met on December 15, it rejected Rutledge’s recess appointment as the nation’s second Chief Justice by a vote of 14-10. Shortly after the vote, Rutledge resigned, having served the shortest tenure of any Chief Justice (138 days).

Pictured below is the notification of the Senate’s rejection of the nomination contained in Washington’s letter book.

The Philadelphia Aurora, a Democratic Republican newspaper, denounced the vote as “an unparalleled instance of party spirit; whether the affront is more aimed at the President, than the Judge is difficult to determine.”

It is the first instance in which [the Senate has] differed from [the president] in any nomination of importance, and what is remarkable in this case, is that the minority of the members on the Treaty were the minority on this nomination.

The partisan lineup on the Senate vote is noteworthy. In 1795, the Senate contained thirty-two Senators (19 Federalists and 13 Democratic Republicans). Interestingly, only twenty-four Senators voted, with eight Senators absent. It is likely that several of the missing Federalist Senators may have preferred not to be on record opposing the nominee of their party’s own President.

Of the ten Senators who voted to confirm Rutledge, only three were Federalists. Of the fourteen votes to reject Rutledge, thirteen were Federalists with only one Democratic Republican voting against confirmation.

Reaction by Adams and Jefferson

John Adams had known and worked closely with Rutledge for decades. Nevertheless, Adams agreed that the rejection of his friend’s nomination was necessary. John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail on December 17, 1795 and explained that:

The Negative put by the Senate on the Nomination of Mr Rutledge gave me pain for an old Friend, though I could not but think he deserved it. C. Justices must not go to illegal Meetings and become popular orators in favour of Sedition, nor inflame the popular discontents which are ill founded, nor propagate Disunion, Division, Contention and delusion among the People.

By contrast, Thomas Jefferson and many Southern Senators who were highly critical of Jay’s Treaty supported Rutledge’s nomination. In a letter dated December 31, 1795, Jefferson wrote to William Branch describing the rejection of Rutledge’s nomination as a “bold” partisan declaration:

The rejection of Mr. Rutledge by the Senate is a bold thing, because they cannot pretend any objection to him but his disapprobation of the treaty. It is of course a declaration that they will recieve none but tories hereafter into any department of the government.

Jefferson’s summary accurately reflects the fact that all fourteen Senators who voted against Rutledge’s nomination also supported ratification of Jay’s Treaty. Of the ten Senators who supported Rutledge, all voted against ratification of Jay’s Treaty, except for James Reade of South Carolina.

Aftermath

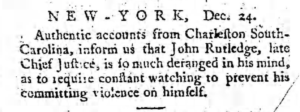

When Rutledge returned to South Carolina, he attempted to commit suicide by jumping off a wharf. He withdrew to spend the remainder of his life in Charleston where he died on July 23, 1800.

As a result of the 14-10 vote, Rutledge became the first rejected Supreme Court nominee. He was also the only recess appointment (of 15 total) who was not subsequently confirmed.

Following the vote, Washington wisely avoided any further controversy by nominating the Senate’s own Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut. Ellsworth was eminently qualified to be the nation’s Third Chief Justice as he was also a framer of the Constitution, as well as being the author of the Judiciary Act of 1789.

Thus, in rejecting Rutledge’s recess appointment, the Senate made clear that it would not only examine a nominee’s qualifications, but also consider political views and temperament.

Additional Reading:

The Documentary History of the Supreme Court, 1789 – 1800 (1985)

John and Edward Rutledge of South Carolina (James Haw, 1997)

The Rutledge Court (Supreme Court Historical Society)

Supreme Court Nominations Not Confirmed, 1789 to Present (Congressional Research Service, 2010)

The Politics of “Advice and Consent” (William Swindler, 1970)

Scalia’s Vacancy in Historical Context (Congressional Research Service, 2017)

Chief Justice Rutledge: An Address. . . (Henry Flanders, 1906)