Presidential Transition Act of 1963

88th Congress, 2nd Session, P.L. 88-277, 78 Stat 153, 3 U.S.C. §102 note 2

Recognizing the importance of seamless presidential transitions, the Kennedy administration recommended the adoption of the Presidential Transition Act of 1963 (hereinafter the “PTA” or “the Act”) to promote the orderly transfer of power following a presidential election.

In adopting the PTA, Congress warned that “[a]ny disruption occasioned by the transfer of the executive power could produce results detrimental to the safety and well-being of the United States and its people.” As the size and complexity of the federal government has increased, the law has been amended several times, confirming the importance of Congress’ intent to “assure continuity in the faithful execution of the laws and in the conduct of the affairs of the Federal Government, both domestic and foreign.”

Mindful of the problems that occurred during prior transitions, in Section 2 of the Act Congress expressed its legislative intent that “all officers of the Government so conduct the affairs of the Government for which they exercise responsibility and authority” for the following purposes:

(1) to be mindful of the problems occasioned by transitions in the office of President, (2) to take appropriate lawful steps to avoid or minimize disruptions that might be occasioned by the transfer of the executive power, and (3) otherwise to promote orderly transitions in the office of President.

Background

The United States has been blessed with peaceful transfers of power since its founding. Yet, until the PTA was adopted in 1963 the transition process was informal and depended in part on the relationship between the incoming and outgoing administrations.

Operating in a world of horse drawn carriages, the framers of the Constitution originally scheduled Presidential inaugurations for March 4. This schedule allowed a five month transition period following the November election. While this may have made sense in a pre-industrial age, it became increasingly clear that an extended lame duck presidency was problematic.

In 1933, the 20th Amendment accelerated the transition process by moving the Presidential term of office to January 20 (and to January 3 for Congress). Prior to this constitutional amendment, the lengthy transition process created uncertainty, particularly during times of crises.

A well known example of a poor transfer of power is the Hoover to Roosevelt transition in 1932–33 during the Great Depression. Hoover had publicly expressed his disagreement with FDR’s legislative initiatives. FDR refused to endorse Hoover’s ideas during the transition. Hoover in turn declined to cooperate with the incoming Roosevelt administration.

In 1952 President Harry S. Truman (who transitioned to office following FDR’s death) started the tradition of giving presidential nominees intelligence briefings. Truman was likely trying to avoid the situation that he faced upon taking office. Historians have learned that upon stepping into the Presidency Truman was unaware of the secret Manhattan Project that would win World War II in the Pacific. After the 1952 election, Truman invited Eisenhower to the White House and ordered federal agencies to assist the former Supreme Allied Commander and war hero.

During the depths of the Cold War, the Kennedy administration certainly understood the national security implications of the transition process. In particular, the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April of 1961 may have been due in part to information lost in translation between the outgoing Eisenhower and incoming Kennedy administrations.

In a letter to Congress dated May 29, 1962 transmitting proposed legislation and recommendations of a bipartisan commission, President Kennedy explained that there were important reasons “to institutionalize the change in party power from one Administration to another”:

An incoming President must select and assemble responsible public officials who must prepare themselves for their new responsibilities. Thus I recommend that the outgoing President be authorized to extend needed facilities and services of the Government to the President-elect and his associates. For this purpose, funds should be appropriated to be spent for specified activities through normal government channels, as the draft legislation provides.

Click here for a link to President Kennedy’s letter to Congress summarizing the legislation and findings of President Kennedy’s Commission on Campaign Costs. The proposed bill was introduced in 1963, but was not enacted until March of 1964. The PTA nonetheless retained its original title as the Presidential Transition Act of 1963 after it was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson (who assumed the Presidency under a more tragic kind of transition).

Text of the Presidential Transition Act

The PTA authorizes office space, services, and funding by the General Services Administration (GSA) to the transition team assembled by the President-elect. Click here for a link to the Act. These resources become available to an “apparent successful candidate” as summarized below.

In 1964, Congress appropriated a sum not to exceed $900,000 for the first publicly funded transition. According to the Act, the GSA Administrator is authorized to provide: 1) suitable office space equipped with furniture and supplies, 2) compensation for staff at the GS-18 pay grade, 3) payment of expenses for experts and consultants, 4) travel expenses and subsistence allowances, 5) communications services, 6) printing expenses and 7) postal reimbursement. Over time, the original $900,000 appropriation grew to $3 million in 1974 and $5 million in 1988. Almost $10 million was allocated for 2020.

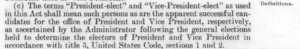

The term “President-elect” and “Vice-President-elect” are defined in Section 3(c) of the Act as “the apparent successful candidates for the office of President and Vice President, respectively, as ascertained by the Administrator following the general elections…”

The legislative history of the PTA indicates that the bill’s primary purpose in 1963 was to minimize the burden of transition financing. Until the Act became law in 1964, the financial burdens of transition expenses was borne by the incoming political party of the new president. According to the House Report, it was important that “sufficient resources are at hand to properly orient the new national leader.”

Two additional motivations are evident in the floor debates. Congressman Dante Fascell (Fla.), the bill’s sponsor, believed that transition “expenses are a legitimate part of the operation of our Federal Government and should be appropriated for like other Government expenses.” Fascell argued that, “[i]t just does not seem proper and necessary to have [the President- and Vice President-elect] going around begging for money to pay for the cost of what ought to be legitimate costs of Government….”

In passing the Act, Congress agreed that the cost of presidential transitions should be borne by the public, not by what Congressman Benjamin Rosenthal (NY) called “special interests…anxiously coming forward to help pay government expense.” Rosenthal worried that lenders would feel “entitled to special consideration” from the incoming government, separate and apart from the optics.

Contested transitions

Section 3(a)’s definition of the term “President-elect” suggests that Congress understood that the decision by the GSA Administrator to trigger a succession was ministerial, not political. It appears that the underlying language regarding the “apparent” winner was lifted from Public Law 87-829, which authorizes the Secret Service to automatically provide protection for the President and Vice-President-elect.

Following the election of 2020, it has been reported that GSA Administrator Emily Murphy is delaying “ascertaining” who won the 2020 election. Murphy was appointed by President Trump in 2017. She holds the power to decide when to trigger the PTA and give President-elect Biden the keys to the transition office (22,000 feet of space at the Commerce Department) and $9.9 million.

If Ms. Murphy decides to await the results of pending litigation brought by the Trump campaign, she will likely point to the precedent set during the contested election of 2000. The GSA during the outgoing Clinton administration declined to provide services for President Bush until the Supreme Court ruling in Bush v. Gore. Click here for a link to the legal opinion from the Office of Legal Counsel in 2000 concluding that there may only be one President-Elect at a time “in circumstances in which it remains unclear after the election which of two candidates will become the President of the United States.” It will be interesting to see whether this 2000 opinion is properly applied in 2020.

Other Transitions

Vice President John Adams was able to comfortably assume the reigns of power when he was elected the nation’s second President in 1796. By contrast, John Adams did not attend President Jefferson’s inauguration following the controversial Election of 1800. The dispute over Adams’ midnight appointment of judges following the election would lead to the landmark decision in Marbury v. Madison.

Nevertheless, newly elected President Jefferson had previously served in Washington’s cabinet. Former Secretary of State Jefferson was thus well prepared for the first peaceful transfer of power between John Adams’ Federalist party and Jefferson’s rising Democratic Republican party. Despite their political differences, Adams and Jefferson would later renew and deepen their friendship, much like President George H.W. Bush and President Clinton.

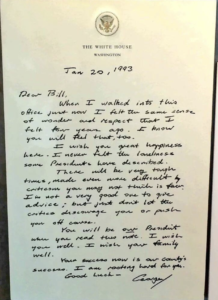

The friendly transition between one term President George H.W. Bush and President Clinton in 1993 provides a poignant example of statesmanship and patriotism. The January 20, 1993 letter speaks for itself and should be recognized as a model of grace, class, and humility. The hand written letter pictured below ends with observation that:

In turn, President Clinton wrote to President George W. Bush that, “I salute you and wish you success and much happiness.” Continuing in this tradition, President George W. Bush wrote to President Obama that the country “is pulling for you, including me.” President Obama wrote to President Trump that, “Michelle and I wish you and Melania the very best as you embark on this great adventure, and know that we stand ready to help in any ways which we can.” Click here for copies of presidential letters by outgoing presidents.

As was the case with his father, President John Quincy Adams refused to attend his successor’s inauguration. One of the most problematic transitions was between James Buchanan and Abraham Lincoln. Following Lincoln’s election, seven states had seceded from the Union during Lincoln’s transition. As Lincoln was being sworn in, eight states were debating secession in March of 1861. Unlike Lincoln, Buchanan believed the Constitution did not empower him to prevent secession, even though he disagreed that states had the constitutional authority to break away from the Union.

After winning the election of 1980, President-Elect Ronald Reagan, “made it clear he wanted nothing to do” with President Carter. According to Carter’s biographer, during their perfectly civil limousine ride to the Capitol on Inauguration Day, Reagan told a series of anecdotes that Carter said “were remarkably pointless.” At the time, Carter was deep in thought about the release of Iranian hostages.

Subsequent Amendments

In 1988 the PTA was amended to require disclosure of financial contributions and the names of transition personnel. A contribution limit of $5,000 was imposed as a condition of receiving taxpayer support.

More recently, the PTA was updated by the Presidential Transitions Effectiveness Act of 1998 (Pub.L. 100–398), the Presidential Transition Act of 2000 (Pub.L. 106–293 (html) (pdf)), the Pre-Election Presidential Act of 2010 (Pub.L. 111–283 (html) (pdf)), the Edward “Ted” Kaufman and Michael Leavitt Presidential Transitions Act of 2015 (Pub.L. 114–136 (html) (pdf)), and the Presidential Transition Enhancement Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-121).

Among other things, these amendments formalize procedures and other protocols for successful and transparent transitions, including providing training and orientation.

Following the 9/11 terrorist attack, the PTA was amended to allow transition-team members to obtain security clearances. An amendment in 2004 directed outgoing officials to prepare a classified national security threat assessment for the incoming President-elect.

The Obama Administration passed two bills addressing shortcomings it experienced in 2008. The Pre-Election Presidential Transition Act of 2010 accelerated the timeline for transition funding, to begin following the party conventions.

The Presidential Transitions Improvements Act of 2015 added new duties for the outgoing administration and GSA. The incumbent President is required to establish coordinating councils and negotiate MOUs governing transition-team privileges. In 2020 the PTA was updated to require an ethics plan addressing conflicts of interest and the role of lobbyists.

Plum Book

In 2020 the incoming administration will be responsible for an estimated 4,000 political jobs, overseeing the nation’s 2 million federal workers. Approximately 1,200 of these appointees require Senate confirmation.

After every Presidential election, the publication “United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions,” commonly known as the Plum Book, is prepared for the new administration. The Plum Book contains data on thousands of federal civil service leadership and support positions that may be subject to noncompetitive appointment (e.g., positions such as agency heads and their immediate subordinates, policy executives and advisors, and aides who report to these officials). Click here for a link to the 2020 Plum Book.

Additional Reading:

Executed original bill (National Archives)

Presidential Transition Act: Provisions and Funding (Congressional Research Service, 2016)

The Law of Presidential Transitions, Joshua P. Zoffer (Yale Lawa Journal, 2020)

Implementation of the 1963 Presidential Transition Act (Paul C Light, Brookings Institute)

Executive Order dated May 6, 2016: Facilitation of a Presidential Transition