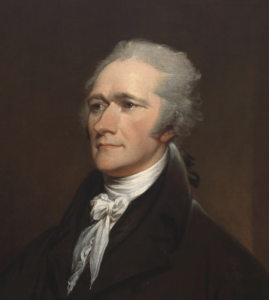

How did Alexander Hamilton (and James Madison) intend the Joint Session of Congress to Operate?

After the Presidential election of 2020, the Joint Session of Congress meeting on January 6, 2021 generated breathless headlines. The largely ceremonial Joint Session is ordinarily a perfunctory exercise when the already ascertained Electoral College votes are officially “counted.” After a dozen Senators announced on January 2, 2021 that they would be objecting to certified electoral votes for President-Elect Biden, it is natural to ask what would Alexander Hamilton, one of the fathers of the Electoral College, think?

For the first time since the disputed election of 1876, President Trump is attempting to set aside properly certified Electoral College votes. Congress adopted the Electoral Count Act of 1887 to avoid a repeat of Hayes – Tilden election of 1876. While it is unlikely that Hamilton and the framers of the Constitution could have imagined electronic voting in 2020, it is nevertheless useful to review Hamilton’s intended operation of the Electoral College.

Background: What does the Constitution say?

After Electoral College votes are formally certified by the governors of all 50 states, the duly certified Electoral College votes are sent to Congress to be officially counted. Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 of the Constitution provides that the Vice President shall “in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted.”

In the event of an Electoral College tie (or if no candidate has a majority), the Constitution provides that the House shall pick a President in what is referred to as a “contingent election.” The House votes by “delegation” during a contingent election and each state has only one vote, regardless of population. It is important, however, not to confuse the specified procedure governing contingent elections with the ordinary procedures governing objections to electoral votes.

Objections by members of Congress to electoral votes are governed by the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (which is codified in Title 3, Chapter 1, of the United States Code). Among other things, the Electoral Count Act requires written, signed objections to be made “clearly and concisely, and without argument.” If at least one member of the House and one Senator submit proper objections, the House and Senate are required to separately consider the objections, with each Senator or Representative limited to five minutes and the debate not exceeding two hours per objection. 3 U.S.C. §15.

Unless the House and Senate both agree with an objection, the Electoral Votes timely certified by a state’s governor are deemed “conclusive.” 3 U.S.C. §5. For this reason, where the House of Representatives is committed to voting down rouge objections, the January 6 outcome is all but certain. Moreover, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell publicly congratulated President-Elect Biden in a speech on the Senate floor on December 15. In a private meeting with the GOP caucus, Senator McConnell asked his Republican colleagues not to force a vote, which would be futile and a “terrible vote.” Nevertheless, it appears likely that a sizable number of Senators led by Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz will submit written objections on January 6.

What would Hamilton say?

While recognition of President-Elect Biden’s victory on January 6th is inevitable, the question remains: What would Alexander Hamilton think about an effort to set aside properly certified electoral votes at the January 6th Joint Session of Congress? What would James Madison have to say about an effort to disregard the will of the electorate, after the courts have dismissed scores of cases brought by or on behalf of a defeated Presidential candidate.

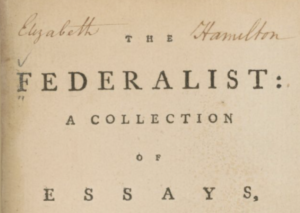

While we cannot read Hamilton’s mind, we have access to the Federalist Papers, Madison’s notes of the Constitutional Convention, ratification debates and other primary sources.

At the Constitutional Convention, Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson described the manner of selecting president as “in truth, one of the most difficult of all we have to decide.” While some delegates advocated for the direct election of the President, others preferred selection by state legislators, or by Congress. Ultimately, as was the case with many provisions, the Electoral College was the result of a variety of compromises.

James Madison and fellow Virginia George Mason argued against granting Congress the power to pick a President due to separation of powers concerns. Alexander Hamilton was particularly concerned with the disadvantages of allowing state legislatures to weaken the Presidency. In his six hour long speech on June 18, 1787, Hamilton initially proposed an Electoral College model under which the President would be selected by “electors, chosen by electors, chosen by the people” in electoral districts. Ultimately, the Committee of Eleven on Postponed Mattes (which included Madison, Roger Sherman, and Gouverneur Morris) formulated the final Electoral College compromise.

Ratification of the Constitution was vigorously contested by the Anti-Federalists. During the Virginia Ratification Convention, Madison spoke at length about “the method of electing the President” on June 18, 1788. Madison emphasized that “the people” choose the electors. According to Madison, “the choice of the people ought to be attended to.”

Hamilton’s views can perhaps best be summarized as follows:

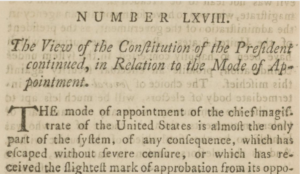

In Federalist 68 Hamilton explained the purpose of the Electoral College and argued that the framers purposely excluded members of Congress from serving as electors to protect the integrity and independence of the electoral process:

- The reason why the Constitution barred members of Congress and federal officials from serving as electors was that they “might be suspected of too great devotion to the president in office.” According to Hamilton, the Electoral College would be “intermediate agents” who would enter into their task “free from any sinister bias.”

Hamilton expressed the concern that Presidential elections could generate dangerous passions which would be minimized by the autonomy provided by the “intermediate body of electors”:

- It was also peculiarly desirable to afford as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder. This evil was not least to be dreaded in the election of a magistrate, who was to have so important an agency in the administration of the government as the President of the United States. But the precautions which have been so happily concerted in the system under consideration, promise an effectual security against this mischief. The choice of SEVERAL, to form an intermediate body of electors, will be much less apt to convulse the community with any extraordinary or violent movements, than the choice of ONE who was himself to be the final object of the public wishes.

Hamilton also worried about cabals, intrigue and corruption that might arise from “deadly adversaries of republican government”:

- Nothing was more to be desired than that every practicable obstacle should be opposed to cabal, intrigue, and corruption. These most deadly adversaries of republican government might naturally have been expected to make their approaches from more than one quarter…But the convention have guarded against all danger of this sort, with the most provident and judicious attention. They have not made the appointment of the President to depend on any preexisting bodies of men, who might be tampered with beforehand to prostitute their votes; but they have referred it in the first instance to an immediate act of the people of America, to be exerted in the choice of persons for the temporary and sole purpose of making the appointment.

Perhaps most overlooked by those who would attempt to set aside the popular vote was Hamilton’s underlying objective in Federalist 68 that “[t]he sense of the people should operate in the choice of the person to whom so important a trust was to be confided…”

Hamilton also had a profound respect for the rule of law. In his Tully No. III letter to the American Daily Advertiser dated August 28, 1794 Hamilton wrote:

- If it be asked, What is the most sacred duty and the greatest source of our security in a Republic? The answer would be: An inviolable respect for the Constitution and Laws — the first growing out of the last.

- A large and well organized Republic can scarcely lose its liberty from any other cause than that of anarchy, to which a contempt of the laws is the high road…

- A sacred respect for constitutional law is the vital principle, the sustaining energy of a free government.

Hamilton also had a deep respect for the role of the courts as “faithful guardians of the Constitution” and would not have wanted to see the judiciary’s role circumvented, as has been proposed by anti-Biden objectors. In Federalist 78 Hamilton famously described the judiciary as the least dangerous of the branches of government, but recognized that judicial independence was the “citadel of the public justice and the public security.”

Hamilton explained that properly functioning and independent courts were necessary:

- “to guard the Constitution and the rights of individuals from the effects of those ill humors, which the arts of designing men, or the influence of particular conjunctures, sometimes disseminate among the people themselves, and which, though they speedily give place to better information, and more deliberate reflection, have a tendency, in the meantime, to occasion dangerous innovations in the government, and serious oppressions of the minor party in the community.”

After the contested Election of 1800, Hamilton proposed amending the Constitution to permit the direct election of Electors. Hamilton’s January 29, 1802 resolution declared that:

- direct election of electors was “a necessary safeguard in the choice of a President and Vice President against pernicious dissension” and the most effective means of “obtaining a full and fair expression of the public will…” By contrast, in 2020 it cannot be said that setting aside millions of votes is in keeping with America’s longstanding tradition of respecting the popular vote.

In sum, Alexander Hamilton would not have supported an effort to set aside properly certified Electoral College votes representing the “sense of the people” – and millions of popular votes – during the January 6th Joint Session of Congress. Nor would Hamilton have looked kindly at efforts to circumvent the courts and the rule of law, as officially certified by 50 governors in accordance with the Electoral Count Act.

Additional Reading:

Electoral College Facts (House.gov)

Five things you need to know about the Electoral College (National Constitution Center)

Who Invented the Electoral College, Philip J. VanFossen

January 2 Joint Statement by Senator Ted Cruz and 10 other Republican Senators

Federalist 68 as originally published in the New York Packet