The Presidential Succession Act of 1792 (and the first law governing the Electoral College) – Part 1

Second Congress, First Session, Ch. 8, §10, 1 Stat. 239 (March 1, 1792)

Presidential succession and the workings of the Electoral College are foundational concepts that underlie the American System of constitutional government. Yet, the first Congressional legislation addressing these topics is easily overlooked and not widely understood.

The Presidential Succession Act of 1792 (hereinafter the 1792 “Act”) was adopted by the Second Congress. The Act was necessitated by the upcoming presidential election, which would unanimously re-elect George Washington. Click here for a link to the Act (contained in the three volume Laws of the United States published in 1796).

The 1792 Act is formally known as “An Act Relative to the Election of a President and Vice-President of the United States, and declaring the Officer who shall act as President in Case of Vacancies in the Office both of President and Vice-President.” Due to its unwieldy name, the Act is commonly referred to simply as “Presidential Succession Act of 1792.”

As reflected by its formal title, the Act covers two subjects relating to the Presidency. The mechanics for the operation of the Electoral Congress is addressed in sections 1 to 8 of the Act. The procedure for filling a vacancy in the event of “removal, death, resignation or inability” of the President or Vice-President is addressed in sections 9 and 10 of the Act.

This post is divided into two parts to discuss both components of the Act. Part I of this post discusses the Electoral College procedures left by the framers of the Constitution to be fleshed out by Congress. Part II (pending) discusses the related issue of Presidential Succession.

The Act’s legislative history will also be reviewed, including the fact that James Madison and the House of Representatives disagreed with the Federalists in the Senate over the order of succession contained in the 1792 Act. It is likely that Federalist fears over placing Jefferson too close to the reins of power may have been at play when Congress selected the President Pro Tempore of the Senate and Speaker of the House to fill presidential vacancies, rather than cabinet officers. Subsequent amendments will also be discussed, along with modern proposals to replace the Electoral College.

Over time, the operation of the Electoral College and the line of Presidential succession have been modified by subsequent legislation, along with the Twelfth, Twentieth and Twenty-fifth Amendments. Nevertheless, analysis of the Presidential Succession Act of 1792 provides valuable insights into the intent of the framers and the original constitutional framework drafted in 1787. In other words, the use of the shortened title “Presidential Succession Act of 1792” is unfortunate since Presidential Succession represents less than one quarter of the content of the act.

Background about the Electoral College:

The phrase “Electoral College” does not appear in the Constitution. The Electoral College is not a formal institution per se, but rather refers to a process that occurs every four years. Article II, Section I, Clause 2, of the Constitution provides for the President and Vice President to be elected using:

a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

The phrase electoral “college” was first codified in the law in 1845. Click here for a link to the Presidential Election Day Act of 1845. The phrase Electoral College was likely borrowed from the Catholic Church’s College of Cardinals, who elect the Pope.

Members of the Electoral College are selected by the respective states, “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct…” Originally, the majority of states did not use the popular vote in presidential elections. Rather, state legislatures commonly voted for President on behalf of the state. By 1832, popular elections replaced state legislatures voting for President.

While Article II, Section I, outlines the process of Presidential elections, it did not answer all procedural questions for the Electoral College. Thus, the 1792 Act fills the gaps that the Constitution left open for Congress to resolve.

Electoral College provisions of the 1792 Act

The First Congress debated the subject of Presidential Succession in 1791, but was unable to approve a bill (as discussed in Part II). With the election of 1792 scheduled for later in the year, the Second Congress resumed work on the matter in early 1792.

The 1792 Act addressed the details left open by the Constitution, including the appointment process for electors, the timing of the meeting of the Electoral College, the governors’ role in national elections, and the surprisingly controversial matter of Presidential Succession.

The 1792 Act established the following procedures for the Electoral College:

- date for appointment of electors: Pursuant to Article II, Section 1, Clause 2, of the Constitution each state is charged with appointing electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct…” Section 1 of the Act provides that “electors shall be appointed in each in each state…within thirty-four days preceding the first Wednesday in December”;

- the number of electors: As specified in Article II of the Constitution, the Act repeated that the number of electors “shall be equal to the number of Senators and Representatives”. Interestingly, Section 1 of the Act clarifies that the number of electors for each state shall be determined based on the most recent apportionment of the incoming Congress, “at the time, when the President and Vice President, thus to be chosen, should come into office.”

- the date for meeting of electors: Section 2 of the Act specifies the electors shall meet and vote on the first Wednesday in December, “at such place in each state as shall be directed by the legislature thereof”;

- voting procedure for electors using triplicate certificates; To create a redundant system, Section 2 provides for electors to sign three certificates of their votes for President and Vice President. The certificates from each state were to be sealed. The Act further provides for the appointment of a person to deliver the certificates to the President of the Senate at the seat of government “before the first Wednesday in January.” In addition to sending the certificates by messenger, a duplicate set was to be sent by the post office. A third set was required to be sent to the federal judge of the district where the electors assembled. These procedural requirements (however outdated they may be) remain in force today;

- duties of the governors of each state: Section 3 of the Act specifies the duties of the “executive authority” of each state to “cause three lists of the names of the electors of such state to be made and certified” and delivered to the electors” prior to the first Wednesday in December. When each elector voted, they were required to “annex one of the said lists to each of the lists of their votes,” in order to verify that the identity of the individual electors.

- back-up procedures and special messenger: In the event that the list of votes from a state had no arrived at the seat of government by the first Wednesday in January, Section 4 of the Act provides that the Secretary of State should send a special messenger to the district judge in whose custody the duplicate list was lodged, who shall forthwith transmit the same to the seat of government.”

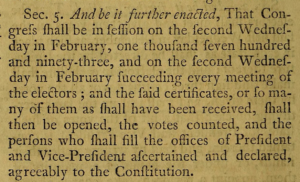

- date for Joint Session of Congress to count the electoral votes: Section 5 of the Act specifies that a Congress shall meet “on the second Wednesday in February” and the votes shall be opened and counted “…and the persons who shall fill the offices of President and Vice-President ascertained and declared, agreeably to the Constitution.” Despite suggestions to the contrary by Texas Representative Louis Gohmert’s lawsuit against Vice President Pence following the 2020 election, Section 5 of the Act assigns no substantive role to the Vice President – as President of the Senate – when votes as “ascertained and declared” at the Joint Session of Congress. Click here for a discussion of why the so-called “Pence Card” is a canard.

- additional details: Section Six provides that if the President of the Senate was not available on the arrival of the persons entrusted with the lists of votes, the messenger shall deliver the lists to the office of the Secretary of State. Section 7 authorized payment of 25 cents per mile for the estimated distance by the “most usual road from the place of meeting of the electors to seat of government of the United States.” In the event that the messenger appointed to deliver the votes neglected to perform their duty, Section 8 specified a penalty of $1,000.

According to the Constitution, each elector would cast two votes for President. The candidate receiving the largest number of votes was elected President, while the recipient of the second highest number of votes was elected Vice President. This procedure did not contemplate the emergence of political parties and was primarily focused on elevating the most qualified candidates to national office.

This process would be revised a decade later by the Twelfth Amendment (which recognizes the reality of party politics and provides for electors to cast separate votes for President and Vice President). Click here for a discussion of the Twelfth Amendment and the Election of 1800 which initially resulted in a tie between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr.

The law would be further revised by the Electoral Count Act of 1887 following the controversial Election of 1876. The 1792 Act, as further amended in 1948, is now codified in Title 3, Chapter 1, of the U.S. Code.

Nevertheless, the basic procedures detailed in the 1792 Act remain the same today, including the recording of three sets of certificates, sending one set by special delivery, one set by mail, and sending a third to the judge of the closest federal district court for safekeeping. It is comforting that in over 200 years, the Electoral College certificates have always arrived on time, and thus the courts have never been called upon to produce their backup copies.

Pictured above is the masthead of one of the leading newspapers in 1792, which printed the entire 1792 Act. Click here for a link to the Gazette of the United States.

As described above, Section 7 of the Act authorized payment of 25 cents per mile for the special messenger delivering the Electoral College certificates to Congress. As Secretary of Treasury in 1792, Alexander Hamilton detailed the precise payments for all 16 states in a “Supplementary estimate” of appropriations that he prepared for Congress. The estimated mileage reimbursements ranged from $7.50 (New Jersey) to $234.25 (Kentucky). At the time, Philadelphia was the nation’s temporary capital in 1792.

Legislative History of the 1792 Act

The Act was adopted in the closing days of the First Session of the Second Congress, on March 1, 1792. The Act was signed into law by President Washington and Vice President Adams, who of course would be the two successful candidates in the upcoming election. The results of the 1792 election were “declared” at a joint session of Congress by Vice President John Adams, as the President of the Senate, on February 13, 1793. Click here for a link to the Annals of Congress.

Unlike the controversial Presidential Succession provisions which are described in Part II (pending), the Electoral College procedures of the Act did not generate much debate. The only objection noted in the Congressional record was the concern by Representative Nathaniel Niles (VT) that requiring the governors to certify the list of electors involved “a blending of respective powers” between the states and the federal government that was “degrading to the Executives of the several states.” For Niles, who was protective of states rights, it was “not warranted by the Constitution” for the federal government to make these specific demands on the states.

Representative Theodore Segdwick (MA) observed that if Congress were not authorized to call upon the governors, “he could not conceive what descriptions of persons they were empowered to call upon.” Representative Abraham Clark (NJ) opined that the Committee was “creating difficulties where none before existed.” For Clark, the selection of electors was a privilege and would “create no uneasiness whatever.” Click here for a link to the Annals of Congress on December 22, 1791.

In fact, Massachusetts Governor John Hancock dutifully complied with the Act, but sent a note to the Massachusetts legislature protesting the purported right of Congress to force governors to certify lists under section 3 of the 1792 Act. In other words, while Hancock was was wiling to comply with the Act’s certification requirements, he did not want to concede powers to Congress. Click here for a discussion of the first presidential elections by historian Edward Stanwood.

Another topic of interest involved the timing of apportionment of electors. The Constitution merely allocates to each state the number of electors based on the number of Senators and Representatives to which each state was “entitled.” The Constitution is silent on the timing of apportionment in the context of presidential elections. The Act answered this question by providing that the allocation shall be based on the new (and more accurate) apportionment of an incoming Congress.

According to historian David Currie, this was “an eminently sensible provision”, but it was not obvious how Congress would resolve this issue. James Madison discussed the issue in a letter to Edmund Pendleton dated February 21, 1792. Madison explains that the northern states stood to lose seats in Congress under the 1790 census and strongly favored using the existing apportionment of the lame duck Congress. Nevertheless, the “intrinsic rectitude” of using the most recent allocation carried the day:

The Bill concerning the election of a President & Vice President and the eventual successor to both, which has long been depending, has finally got thro’ the two Houses. It was made a question whether the number of electors ought to correspond with the new apportionment or the existing House of Reps. The text of the Constitution was not decisive, and the Northern interest was strongly in favor of the latter interpretation. The intrinsic rectitude however of the former turned the decision in both houses in favor of the Southern.

Madison’s letter also discusses the controversy over presidential succession, which will be addressed in Part II (pending) of this post. Due to disagreement over the line of presidential succession, the Act narrowly passed by a vote of 31-24 in the House and 27-24 in the Senate. Copies of the Act are pictured below.

Discussion of the Electoral College in 1792

The Presidential election of 1792 was the first contested Presidential election in American history. George Washington was unanimously re-elected by the Electoral College to a second term. While Washington effectively ran unopposed, the newly emerging political parties contested the Vice Presidency. Federalist John Adams was re-elected Vice President. Yet, Adams was opposed by New York Governor George Clinton, who ran as the Democratic-Republican party candidate.

By 1792, the original 13 colonies had grown to 15 states with the addition of Kentucky, and Vermont. At the time, only 6 of the 15 states selected electors by popular election (Virginia, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Hampshire and Kentucky). In the remaining 9 states the state legislatures selected the Presidential electors and instructed them how to cast their vote for President.

Proposals to Replace the Electoral College

Professor Arthur M. Schlesinger described the Electoral College as a “mystic agency between the electorate and the President.” In Schlesinger’s opinion, the Electoral College “systematically distorts the popular vote,” is not understood by most Americans and is “impossible to explain to foreigners.”

Several presidents, including Andrew Jackson, Richard Nixon, and Jimmy Carter have proposed replacing the Electoral College. In his first annual message to Congress in 1829, President Jackson observed that, “[t]o the people belongs the right of electing their Chief Magistrate.” Jackson argued that, “[a] President elected by a minority can not enjoy the confidence necessary to the successful discharge of his duties.” Almost 150 years later, in 1977 President Carter proposed a constitutional amendment for the direct popular election of the President which would “ensure that the candidate chosen by the voters actually becomes President.”

Five time in American history the candidate who won the popular vote lost the presidential election:

- Andrew Jackson lost to John Quincy Adams in 1824

- Samuel Tilden lost to Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876

- Grover Cleveland lost to Benjamin Harrison in 1888

- Al Gore lost to George W. Bush in 2000

- Hillary Clinton lost to Donald J. Trump in 2016.

In 2004, the Congressional Research Service found that reform of the Electoral College has generated more proposed constitutional amendments than any other subject. In 1969, the proposed Bayh-Celler amendment would have replaced the Electoral College with a two-round (or runoff) system under which a second ballot is used if the winner of the first round does not obtain 40% of the vote. The Bahy-Celler proposal (H.J. Res. 681) passed in the House by a vote of 339 to 70. Even though President Nixon supported the amendment, the proposed amendment failed to pass in the Senate in 1970 after it was filibustered by Southern Senators and small state conservatives.

Additional Reading:

The Constitution in Congress: The Federalist Period 1789-1801, 136, David P. Currie (1997)

Counting Electoral Votes: An Overview of Procedures at the Joint Session, Including Objections by Members of Congress (Congressional Research Service, 2020)

Electoral College History (National Archives)

Electoral College & Indecisive Elections (House.gov)

Presidential Election of 1792: A Resource Guide (Library of Congress)

A History of the Presidency from 1788 to 1897, Edward Stanwood (1898)

A History of the People of the United States, John Bach McMaster (1915)

The Cycles of American History, Arthur Schlessinger, Jr. (1986)