Hamilton and the Third Confederation Congress (1782-1783)

Alexander Hamilton served in Congress during one of the most eventful, but tumultuous years in American history. This post tells the story of Hamilton’s frustrating but formative term in the Third Confederation Congress. Also discussed below is an analysis of Hamilton’s committee assignments from November 25, 1782 to July 30, 1783. This post argues that due in part to Hamilton’s outspoken advocacy in Congress, most if not all of the delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 would have been familiar with Hamilton’s unabashed reputation as a leading nationalist.

No authoritative study of Alexander Hamilton’s time in Congress has been written. Most of Hamilton’s biographers devote but a handful of pages to Hamilton’s self-described “apprenticeship” in Congress. Yet, it is clear that during his single term in office Hamilton developed a reputation as an ardent nationalist. In particular, Hamilton unsuccessfully attempted to strengthen Congressional power and raise funds for the nation’s mounting war debts. Click here for a discussion of the proposed federal Impost of 1783 which was championed by Hamilton and Madison.

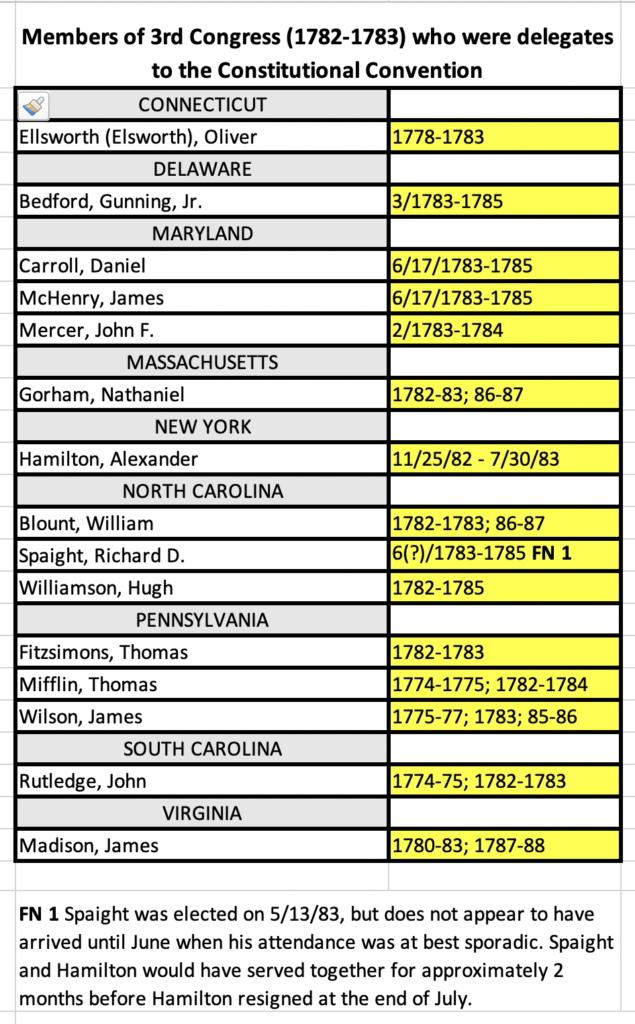

As described below, during his brief tenure in Congress Hamilton worked with fourteen other Congressional colleagues who would later join him at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia four years later. These delegates came from eight of the twelve states which attended the Constitutional Convention and would comprise one-fourth of the fifty-five delegates at the Convention.

Interestingly, thirteen of the fourteen framers of the Constitution who were Hamilton’s Congressional colleagues would sign the Constitution in 1787. This is not to say that all members of Congress supported the Constitution. Famous anti-Federalists who served in the Confederation Congress included Elbridge Gerry and Samuel Adams (Massachusetts), Melancton Smith and John Lansing, Jr. (New York), Luther Martin (Maryland), and Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee and James Monroe (Virginia). Nevertheless, the Congressional term of these anti-Federalists did not overlap with Hamilton between 25 November 1782 to 30 July 1783. One can speculate whether ratification would have been easier if more anti-Federalists had served with Hamilton during the critical years of 1782-1783.

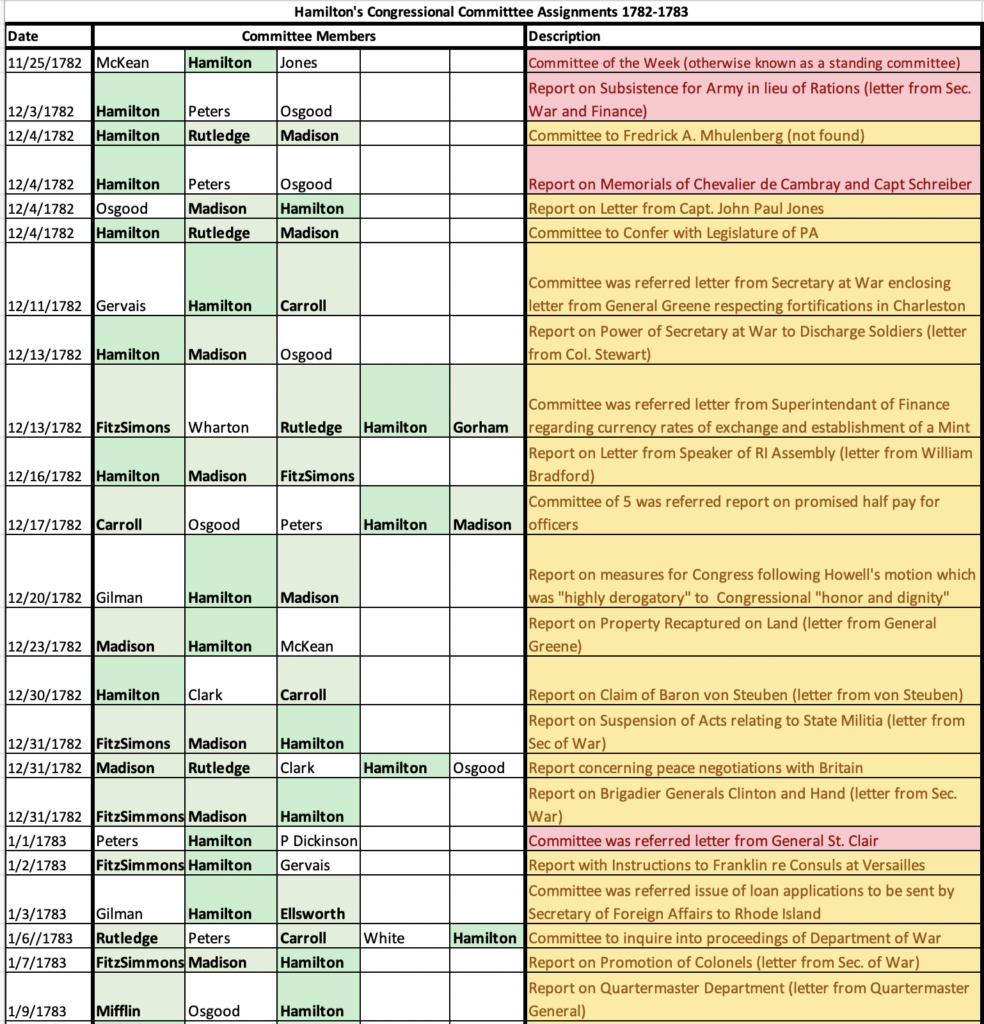

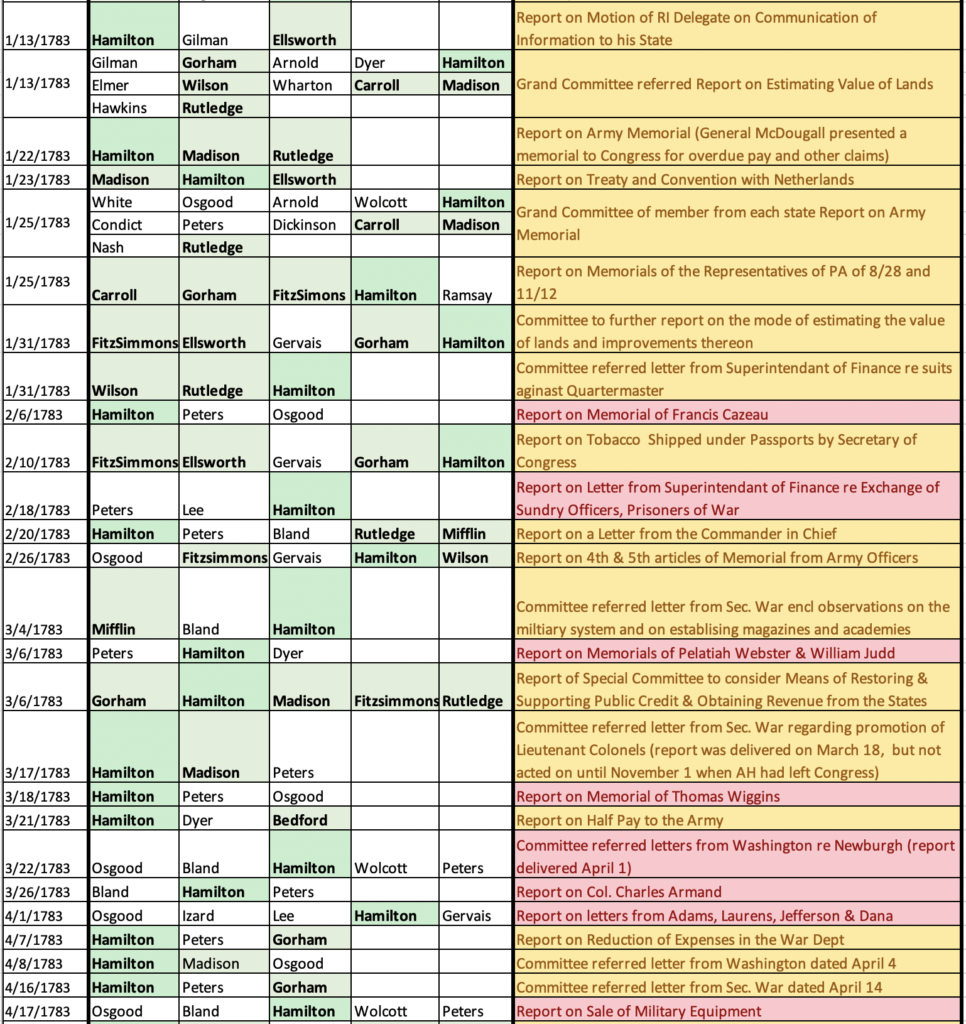

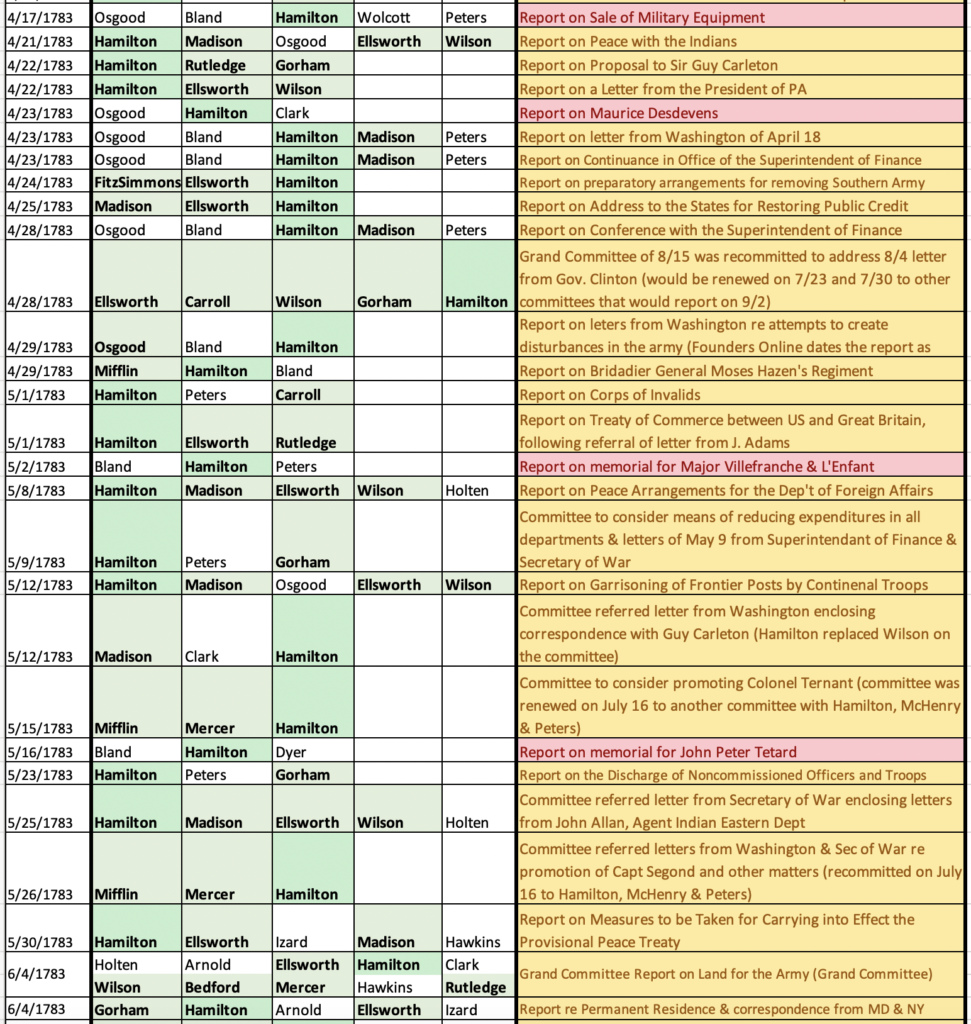

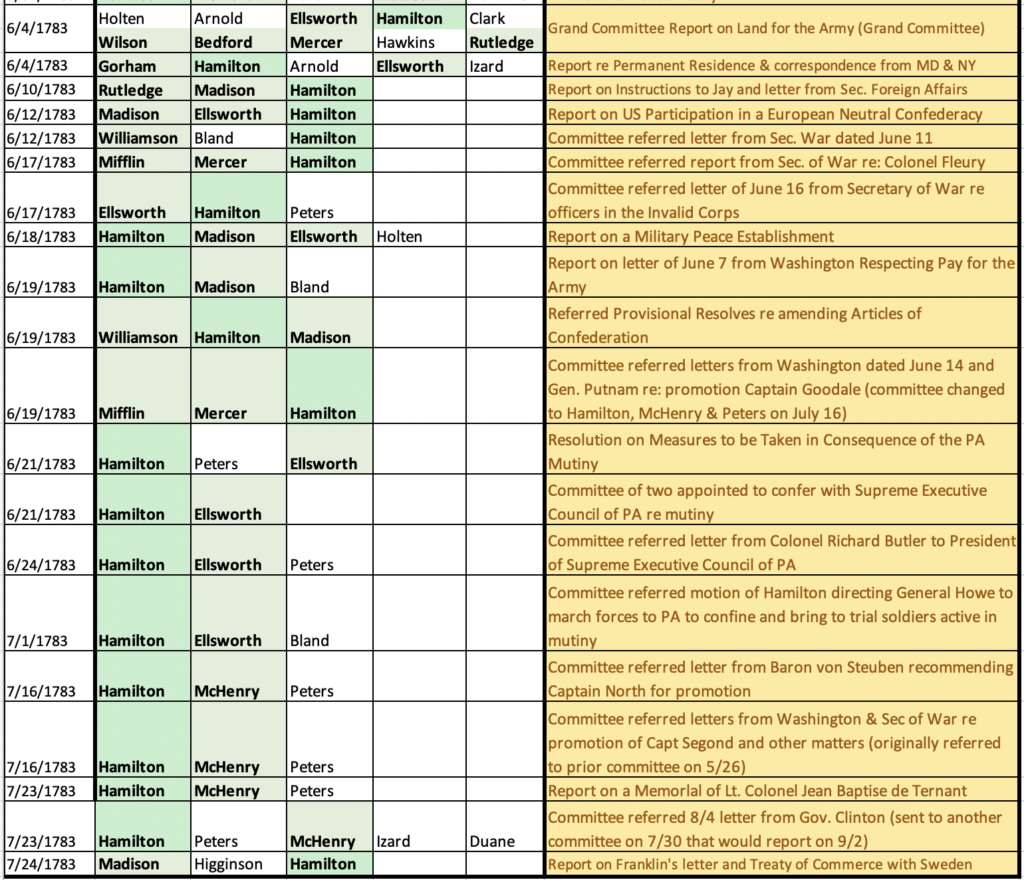

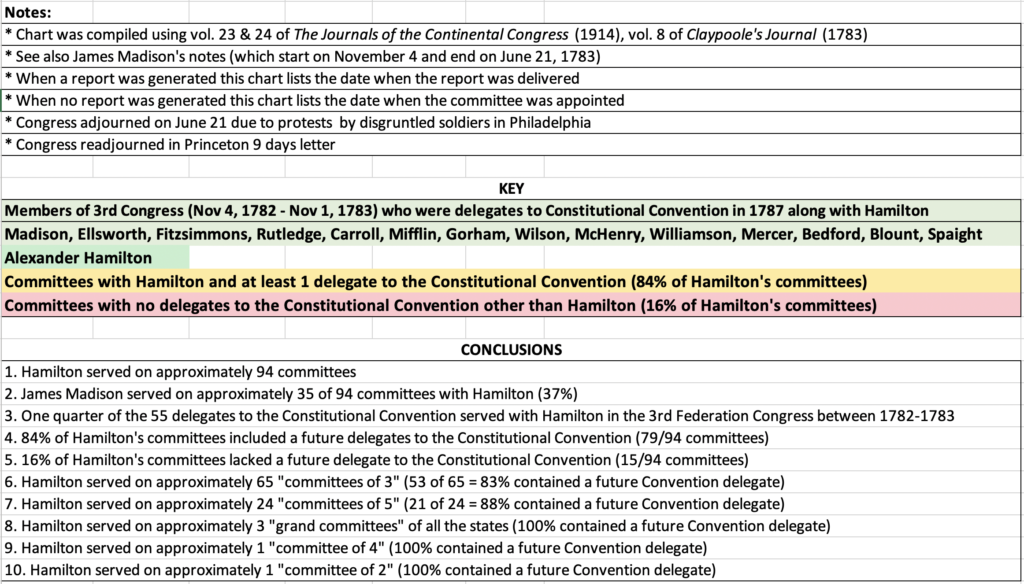

Significantly, 84% of the 94 committees that Hamilton sat on during his eight months in Congress included at least one future delegate to the Constitutional Convention. Indeed, as illustrated by the chart which is set forth at the end of this blog post, it was not unusual to find that Convention delegates had served together on multiple committees. In fact, nearly a quarter of Hamilton’s committees (23 of 94) were composed entirely of future Convention delegates.

It is thus not surprising that James Madison served together with Hamilton on more than 1/3 of all of Hamilton’s committee assignments (35 of 94 committees). Fully 1/4 of the 55 delegates who attended the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia served with Hamilton in the Third Confederation Congress from 1782-1783, representing 33% of the signers (13 of 39).

In summary:

- Hamilton served on approximately 94 committees between 11/1782 to 7/1783;

- Almost all of Hamilton’s congressional colleagues at the Constitutional Convention supported and signed the Constitution in 1787 except for John Mercer of Maryland;

- James Madison served on approximately 35 of 94 committees with Hamilton (37%);

- A quarter of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention (14/55) served with Hamilton in the Third Federation Congress between 1782-1783;

- 84% of Hamilton’s committees included a future delegate to the Constitutional Convention (79/94 committees);

- Only 16% of Hamilton’s committees lacked a future delegate to the Constitutional Convention (15/94 committees)

As discussed below, this data is taken from volume VIII of the Journal of the United States, in Congress Assembled (Clapypoole 1783) and volume XXIII and XXIV of the Journals of the Continental Congress (GPO, 1914 & 1922).

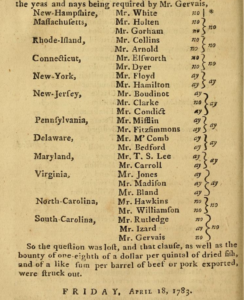

Typically less than 30 delegates appeared on any given day. As Hamilton would later observe, it was within the power “of a small combination to retard and even to frustrate the most necessary measures…” A sample page from the Journal of the Confederation Congress showing a vote tally is copied below.

Hamilton’s background prior to his appointment to Congress:

Following the battle of Yorktown, in March of 1782 Hamilton resigned his military commission to return home to Eliza and his infant child, Philip, in New York. After 6 months of studying law in Albany, Hamilton was admitted to the New York bar in July of 1782.

Hamilton understood the dire need for Congress to raise funds. Hamilton was appointed receiver of continental taxes for New York by Robert Morris, the nation’s powerful Superintendant of Finance who was instrumental in financing the Continental Army. Hamilton would later replace Morris as the nation’s first Secretary of Treasury in 1789.

Despite his best efforts in 1782, Hamilton was unable to raise additional revenue from New York. While major military operations had ceased, much of New York was still occupied by the British. English troops would not depart New York City until “Evacuation Day” on 25 November 1783, pending the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris to end the war. Hamilton summarized “the full situation and temper” of the state in a detailed report to Morris dated August 13, 1782.

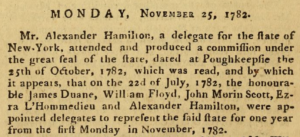

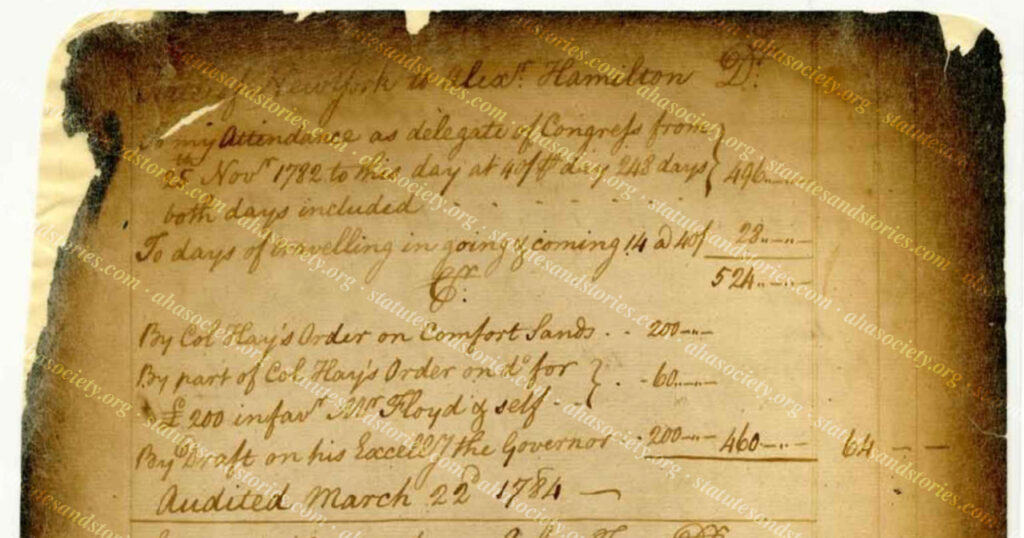

After briefly working for Morris, Hamilton was appointed to the Confederation Congress as a delegate from New York for a one-year term beginning in November 1782. He presented his credentials to Congress in Philadelphia on November 25, 1782. Eight months later, a frustrated Hamilton would resign from Congress in July of 1783 following one of the most tumultuous Congressional sessions in American history.

Issues facing the Third Confederation Congress

As described by historian Forrest McDonald, Hamilton “arrived just in time to play a role in the climactic act of the politics of the Revolution.” Among the issues confronting Congress as the war was in the process of winding down were: 1) paying war debts, including outstanding pay and pensions for soldiers; 2) demobilizing the army which was becoming disgruntled; 3) approving a pending peace treaty with Britain and establishing relations with other international powers, including indigenous peoples; 4) reintegrating loyalists as American citizens; and 5) resolving trade and boundary issues between the states, including the contentious dispute with New York over independence for Vermont.

Further complicating Congress’ job was the so-called “Newburgh Conspiracy” by army officers which would erupt in March of 1783. Three months later, in June of 1783, a general mutiny by soldiers stationed in Lancaster, Pennsylvania forced Congress to flee the capitol and relocate in Princeton, New Jersey.

In 1781, Congress proposed a tax on imports to provide needed revenue. Click here for a discussion of the failed Impost of 1781. All states except Rhode Island had approved the proposed impost tax, which required a unanimous vote to give Congress independent taxing power. Congress not only lacked independent taxing power under the Articles of Confederation, it also lacked the power to regulate trade, at a time when British imports were beginning to flood into the country in 1783.

Hamilton’s arrival

According to historian Willard Sterne Randall, Hamilton’s entry into Congressional politics came at a time “when Congress was at its weakest, challenged by the states at every turn.” Hamilton was not overly optimistic when he took his seat in Philadelphia. Hamilton wrote to his good friend John Laurance on 12 December 1782, “God grant that the union may last, but it is too frail now to be relied on, and we ought to be prepared for the worst.”

Without revenue Congress could not afford to pay the army which was still in the field. Nor could Congress make interest payments on its debts, which was important to secure more foreign loans. The pending conclusion of the war, while certainly good news, lessened the pressure on the states to pay the pending “requisitions” requested by Congress. As described by historian Broadus Mitchell, “the urgency of war had obscured the political problem.” How would the need for Congressional power to address pressing national issues be reconciled with state sovereignty and individual liberty, at the conclusion of a war fought against royal authority?

Before Hamilton left New York for Philadelphia, he worked with his father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, to prepare a Resolution of the New York Legislature calling for a Convention of States to Revise and Amend the Articles of Confederation. The Resolution declared that, “the radical source of most of our embarrassment is the want of sufficient power in Congress…” Hamilton’s Resolution was approved by the New York Legislature on July 22, 1782. Hamilton no doubt hoped that Congress would agree and call for a Convention to amend the Articles. It was not to be.

Before departing Congress a year later, Hamilton noted that his draft Congressional Resolution “intended to be submitted to Congress at Princeton in 1783” was “abandoned for want of support.” The idea of a convention would need to wait until 1787.

Instead, upon arriving at Congress Hamilton was confronted by more intransigence from Rhode Island. One of Hamilton’s first motions, on 11 December 1782, was to give direction to the Superintendent of Finance to communicate to the states the “indispensable necessity for their complying with the requisitions of Congress” seeking to raise $1,200,000 for paying interest on accumulated debts and $2,000,000 for defraying expenses. Included in Hamilton’s motion was the request to send a delegation to Rhode Island to urge “the absolute necessity” of compliance with the Impost of 1781.

Hamilton was then tasked with drafting the letter to be presented to Governor William Greene of Rhode Island. Hamilton’s letter ended with the bold request that “if the Legislature should not be sitting, it may be called together as speedily as possible…” to meet with the delegation that Congress was sending to Rhode Island.

Unfortunately, before the Congressional delegation could arrive, Rhode Island rejected the impost. In a letter from the William Bradford, the Speaker of Rhode Island’s Assembly, the maverick state listed its objections to the impost. Naturally, Hamilton’s committee was selected to respond to Bradford’s objections.

In a reply dated 16 December 1782 Hamilton provided a strong defense of Congressional power and systematically refuted each of Rhode Island’s objections. While a detailed discussion of Hamilton’s report is beyond the scope of this post, Professor Nathan Coleman has observed that the foundation of Hamilton’s thinking is present in what can be viewed as his “first mature state paper.” Hamilton’s reply to Rhode Island also provided Hamilton his first opportunity to expand upon his plans “to fund the debt and render the evidences of it negotiable.”

Besides the advantage to individuals from this arrangement, the active stock of the nation would be increased by the whole amount of the domestic debt, and of course the abilities of the community to contribute to the public wants. The national credit would revive and stand hereafter on a secure basis.

Hamilton’s response to Bradford was also Hamilton’s first of many collaborations with James Madison. All of Hamilton’s committee assignments are set forth in the spreadsheet below. Among other important committees, Hamilton chaired the committee that developed the first plan for establishing an army in peacetime. When Robert Morris threatened to quit as Superintendent of Finance, Hamilton was selected for the committee to persuade Morris to stay. When a mutiny by unpaid Pennsylvania troops marched on the capital, Hamilton was assigned to the committee responsible for addressing the crisis.

“Full of energy and ideas,” Hamilton biographer Marie Hecht explains that “twenty-five-year-old Hamilton plunged into controversy over every issue that presented itself.” Yet, the underlying weakness of the Articles of Confederation would undermine Hamilton’s efforts at reform. Nevertheless, Hamilton had an opportunity to work with Madison and other members of Congress who shared Hamilton’s thinking.

According to historian Willard Sterne Randall, Hamilton “made friends and built alliances with the brilliant handful of founders left over from the glorious days of 1776.” Thus, Hamilton “won the respect” of the following fourteen committee members that he served with in the Third Congress:

Copied below is a chart of the 94 committees that Hamilton served on, including the 38 he chaired. A subsequent post will further expound upon the thesis that when the Constitutional Convention met in May of 1787, Hamilton’s reputation as a leading nationalist preceded him to Philadelphia.

Additional Reading and Sources:

Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow (2004)

Alexander Hamilton: A Life, Willard Sterne Randall (2003)

Alexander Hamilton: American, Richard Brookhiser (1999)

Odd Destiny: The Life of Alexander Hamilton, Marie B. Hecht (1982)

Alexander Hamilton: A Biography, Forrest McDonald (1979)

Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox, John C. Miller (1959)

Alexander Hamilton: Youth to Maturity, 1755-1788, Broadus Mitchell (1957)