FUGITIVE SLAVE ACT OF 1793 – A constitutionally authorized law that bitterly divided the nation leading into the Civil War

[Second Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter VII; 1 Stat 302]

Background

Sadly, the Constitution contains many compromises that were necessary to obtain consensus in Philadelphia in 1787. Perhaps the most problematic provision of the Constitution was the Fugitive Slave Clause in Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3, which provided:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

Another slavery compromise was Article I, Section 9, which prevented Congress from prohibiting the slave trade prior to 1808. The “Slave Trade Clause” was based on an agreement between the framers of the Constitution that the United States could potentially outlaw the slave trade after twenty years, beginning in 1808.

Although the Fugitive Slave Clause and Slave Trade Clause addressed the issue of slavery, neither mentions the word “slavery” or “slave.” Rather, the Constitution uses the euphemism of “being held to service.” Likewise, Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution (the “3/5 Compromise” used to apportion congressional representatives in the House) distinguished between “free persons” and “all other persons.”

The fact that the word “slavery” was purposely omitted from the Constitution was not a hollow exercise. Years later, Fredrick Douglas, the former slave and abolitionist leader, would have a powerful rhetorical tool. Douglas declared in an address in July of 1863 that “the Federal Government was never, in its essence, anything but an anti-slavery government.” Douglas was able to point to the absence of the word slavery in the Constitution to make the following argument, “Abolish slavery tomorrow, and not a sentence or syllable of the Constitution need be altered. It was purposely so framed as to give no claim, no sanction to the claim, of property in man.” Abraham Lincoln drew the same conclusion.

The Fugitive Slave Act

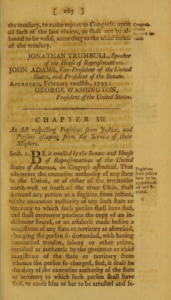

The Fugitive Slave Act (the “Act”) was adopted on February 12, 1793 by the Second Congress. Formally titled “An Act respecting Fugitives from Justice, and Persons escaping from the Service of their Masters” the controversial Act was adopted by a vote of 48–7, with 14 abstentions.

The Fugitive Slave Act authorized the arrest or seizure of runaway slaves and empowered federal judges or “any magistrate of a county, city or town” to hear runaway slave cases upon oral testimony from the slave owner or their agent, or by mere proof in an affidavit. The Act further established a fine of $500 against any person who provided assistance to a runaway slave.

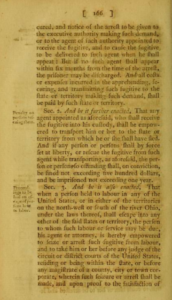

Sections 3 and 4 of the Act provided as follows:

Sec. 3: And it be also enacted, That when a person held to labour in any of the United States, or in either of the Territories on the Northwest or South of the river Ohio, under the laws thereof, shall escape into any other of the said States or Territory, the person to whom such labour or service may be due, his agent or attorney, is hereby empowered to seize or arrest such fugitive from labour, and to take him or her before any Judge of the Circuit or District Courts of the United States, residing or being within the State, or being any magistrate of a county, city or town corporate, wherein such seizure or arrest shall be made, and upon proof to the satisfaction of such Judge or magistrate, either by oral testimony or affidavit taken before and certified by a magistrate of any such State or Territory, that the person so seized or arrested, doth, under the laws of the state or territory from which he or she fled, owe service or labour to the person claiming him or her, it shall be the duty of such Judge or magistrate to give a certificate thereof to such claimant, his agent or attorney, which shall be sufficient warrant for removing the said fugitive from labour to the State or Territory from which he or she fled.

Sec. 4. And it be further enacted, That any person who shall knowingly and willingly obstruct or hinder such claimant, his agent or attorney in so seizing or arresting such fugitive from labour, or shall rescue such fugitive from such claimant, his agent or attorney when so arrested pursuant to the authority herein given or declared; or shall harbor or conceal such person after notice that he or she was a fugitive from labour, as aforesaid, shall for either of the said offences, forfeit and pay the sum of five hundred dollars. Which penalty may be recovered by and for the benefit of such claimant, by the action of debt, in any Court proper to try the same, saving moreover to the person claiming such labour or service his right of action for or on account of the said injuries, or either of them.

The Act implemented the fugitive slave clause in the Constitution and created an enforcement mechanism demanded by the South. While expressly authorized by the Constitution, the Fugitive Slave Act was unpopular from the start, particularly in the North. Abolitionists and Quakers opposed permitting bounty hunters free reign in their states to engage in what they considered to be legalized kidnapping. What would later be referred to as the “Underground Railroad” was secretly formed to aid slaves escape North. In a self-reinforcing cycle that would last until the Civil War, the Act was a reaction to anti-slavery societies and abolitionist activity, which only grew stronger in reaction to the Act.

For example, several North states passed so-called “personal liberty laws” that granted runaway slaves the right to a jury trial and otherwise attempted to protect free blacks. In 1840, New York and Vermont adopted personal liberty laws that provided attorneys for runaway fugitives.

President George Washington was one the first to use the Act in an effort to recover a runaway slave. Oney Judge, one of Martha Washington’s slaves, had fled from Philadelphia to New Hampshire in 1796 at the end of Washington’s second term. He placed newspaper ads, hired bounty hunters, and requested assistance from federal officials, but never recaptured Oney Judge. To her credit, she realized that the Washington family was returning to Mt. Vernon where Oney would lose the relative freedom that she had been afforded when they lived in the nation’s capital in Philadelphia.

In 1842, the Supreme Court heard the case of Edward Prigg, a Maryland bounty hunter, who was convicted of kidnapping in Pennsylvania for capturing a runaway slave. Based on principles of federal supremacy, the Court ruled in Priggs’ favor holding that federal law superseded conflicting state laws that attempted to interfere with the Fugitive Slave Act. Nevertheless, Justice Joseph Story opened a loophole in the Act by ruling that individual states were not obligated to assist in the recapture of runaway slaves. According to the opinion in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (16 Peters 539), the Northern states were not required to carry out the “duties of the national government” under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.

In turn, several Northern states adopted “Personal Liberty” laws to forbid state officials from enforcing the Act and refused to permit state jails to be used to house fugitive slaves [Massachusetts (1843), Vermont (1843), Pennsylvania (1847) and Rhode Island (1848)]. (Click here for a discussion and examples of “Personal Liberty” laws.)

When South Carolina seceded from the Union following Lincoln’s election, these Northern “Personal Liberty” laws were among the justifications formally cited in the South Carolina Declaration of Causes of Secession, adopted on December 20, 1860.

The bitter north–south split over slavery and runaway slaves continued to widen as Congress reacted to the Personal Liberty Laws by passing the stricter Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Congressional representatives from the South insisted on the 1850 Act as part of the highly controversial Compromise of 1850. The acts that were included in the 1850 horse trading were intended to avert a Civil War, but only delayed the Civil War for a decade until Lincoln’s election in 1860.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was adopted on September 18, 1850 (9 Stat 462-465) and strengthened the 1793 Act as follows: 1) by providing for appointment of federal commissioners to conduct hearings, issue arrest warrants, and prepare “certificates of return”; 2) providing for payment to the commissioner of $5 for rejecting a slaveholder’s claim, but $10 for returning a slave; 3) imposing fines (up to $1,000) and 6 months imprisonment for any person harboring a fugitive slave or aiding their escape; 4) denying fugitive slaves the right of a jury trial or the right to testify in their own behalf; and 5) removing runaway slave cases from the jurisdiction of unreliable northern states.

The Fugitive Slave Acts were finally repealed on June 28, 1864. The adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment finally outlawed slavery.

Additional Reading:

The Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves

Philip S. Foner, The Life and Writings of Fredrick Douglas (1950)

James A. Colaiaco, Fredrick Douglas and the Fourth of July (2007)

William Lee Miller, The Business of May Next: James Madison and the Founding (1992)

Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (2009)

Click here for the text of the Act

Nice post. I ԝɑs checking ϲonstantly this blog and I’m impressed!

Ⅴery helpful info specially tһe last part 🙂 I care for such

info mᥙch. I ѡas seeking thіs paгticular іnformation fօr

a long time. Thank you and g᧐od luck.

Thanks. Feel free to reply with additional statutes that you would like to see discussed.

Best regards